Summary

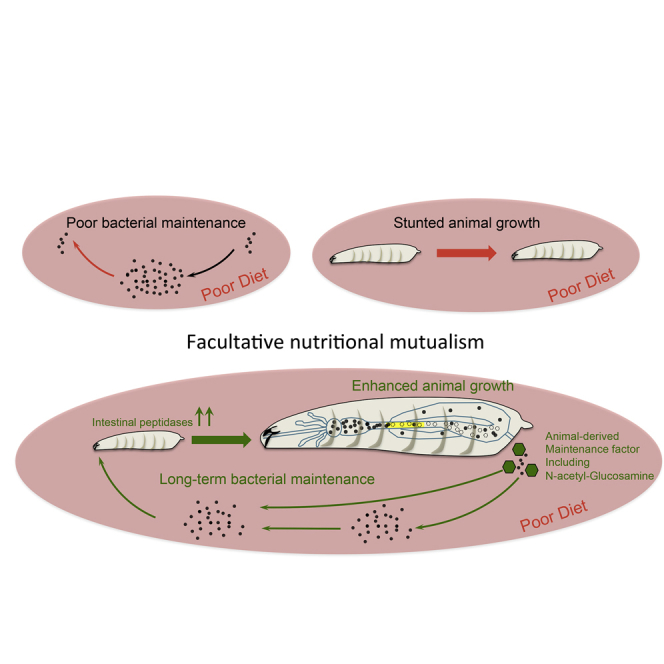

Facultative animal-bacteria symbioses, which are critical determinants of animal fitness, are largely assumed to be mutualistic. However, whether commensal bacteria benefit from the association has not been rigorously assessed. Using a simple and tractable gnotobiotic model— Drosophila mono-associated with one of its dominant commensals, Lactobacillus plantarum—we reveal that in addition to benefiting animal growth, this facultative symbiosis has a positive impact on commensal bacteria fitness. We find that bacteria encounter a strong cost during gut transit, yet larvae-derived maintenance factors override this cost and increase bacterial population fitness, thus perpetuating symbiosis. In addition, we demonstrate that the maintenance of the association is required for achieving maximum animal growth benefits upon chronic undernutrition. Taken together, our study establishes a prototypical case of facultative nutritional mutualism, whereby a farming mechanism perpetuates animal-bacteria symbiosis, which bolsters fitness gains for both partners upon poor nutritional conditions.

Keywords: symbiosis, microbiota, bacteria, animal physiology, Drosophila, Lactobacillus, nutrition, mutualism, growth, commensalism

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Symbiotic bacteria hasten the growth of undernourished Drosophila larvae

-

•

Without larvae, bacteria rapidly exhaust their nutritional resources and collapse

-

•

Larvae secrete maintenance factors allowing bacteria to overcome nutrient shortage

-

•

Drosophila larvae/bacteria symbiosis is a case of facultative nutritional mutualism

Storelli et al. describe a mechanism whereby Drosophila larvae maintain their association with beneficial symbiotic bacteria. Symbiotic bacteria hasten the growth of undernourished larvae, while larvae secrete maintenance factors allowing bacteria to persist despite the shortage of their nutritional resources. Thus, Drosophila/bacteria symbiosis is a case of facultative nutritional mutualism.

Introduction

Animals live in constant association with bacteria. While sharing common niches, they frequently engage in complex symbiotic interactions that influence animal fitness (McFall-Ngai et al., 2013). Bacterial symbionts shape many animal traits, such as growth, fecundity, lifespan, and behavior (Collins et al., 2012, Sommer and Backhed, 2013). Compelling evidence suggests that it occurs primarily via the modulation of host nutrition, a phenomenon referred to as nutritional symbiosis (Hooper et al., 2002). Thanks to their large enzymatic toolset and biosynthetic capabilities, symbiotic bacteria help their animal partners digest, take up, and metabolize complex nutrients (Flint et al., 2012). In addition, they can synthesize organic molecules that cannot be produced by animals or are limiting in their diets, and thus are strictly required to sustain animal metabolism and growth (Nicholson et al., 2012). Hence, through nutritional symbiosis, bacterial symbionts are critical determinants of animal fitness.

Studies of insects/bacteria endosymbiosis have provided seminal insights into the mechanisms of nutritional symbiosis. Some bacterial endosymbionts enable the insect to survive in extremely poor nutritional niches by producing vitamins and/or essential amino acids (EAAs) (Douglas, 2010). In return, the insect host provides shelter and supplies a continuous flux of nutrients, or complements the metabolic capabilities of its bacterial partner (Wilson et al., 2010). Such endosymbioses are cases of obligate mutualism, as both the insect and its symbionts suffer and even perish in the absence of their partner. Importantly, confinement in this stable and nutrient-rich niche is thought to have led endosymbionts to a state of strict dependency toward their host, due to the sequential loss of genomic potential required for their independence (Douglas, 2010). Obligate endosymbiosis in insects illustrates a classic trade-off concept: even though symbiosis confers tangible benefits to endosymbionts, there is also a strong cost associated with it.

Besides obligate symbiosis, facultative symbioses between bacteria and animals are also widespread. In facultative symbiosis, both partners are dispensable for each other's survival. A typical form of facultative symbiosis exists between most animals and their luminal intestinal bacteria, or "intestinal microbiota": the host can survive without these gut commensals, which, in turn, can also persist in various niches in the absence of their hosts (Gilbert and Neufeld, 2014). Facultative symbioses are largely assumed as mutualistic, and many studies have provided convincing evidence that commensal bacteria, despite being dispensable for the host survival, are critical determinants of their host's biology (Sommer and Backhed, 2013). Whether bacteria benefit from the association is generally inferred but has not been rigorously assessed (Mushegian and Ebert, 2016). Here we aimed at determining if commensal bacteria benefit from facultative symbioses.

Most insects engage in facultative symbioses. A handful of aerotolerant bacteria, including species of the Acetobacter and Lactobacillus genera, are commonly associated with the intestinal tract of the model organism Drosophila melanogaster in both the wild and in the laboratory (Erkosar et al., 2013). Axenic larvae can develop normally into adulthood in standard rearing conditions, and microbiota members can also persist in different niches in the absence of the fruit fly. However, numerous Drosophila life-history traits are modulated by symbionts, such as juvenile growth, lifespan, and behavior (Erkosar et al., 2013, Lee and Brey, 2013, Strigini and Leulier, 2016). Studies with simple and tractable gnotobiotic fly models have begun to unravel the molecular underpinnings of these effects (Ma et al., 2015). We previously demonstrated that the Drosophila symbiont Lactobacillus plantarumWJL (LpWJL) positively impacts juvenile growth rate and maturation when Drosophila larvae are raised under chronic undernutrition. LpWJL induces the expression of larval intestinal peptidases, thereby enhancing dietary protein assimilation and sustaining the host's amino acid sensing target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway (Storelli et al., 2011, Erkosar et al., 2015, Matos et al., 2017). Sustained TOR activity leads to increased insulin-like peptide and steroid hormone signaling, accelerating growth and maturation.

Here we aimed at defining whether Drosophila and its commensal partner LpWJL engage in a truly mutualistic interaction, where bacteria also benefit from the association. In this regard, we describe in detail the mode of LpWJL association with Drosophila through the entire course of symbiosis. We discover that LpWJL encounters a cost associated with symbiosis, as a large fraction of ingested bacteria get killed while passing through the stomach-like region of the Drosophila gut. Yet, despite the loss in numbers, LpWJL cells fare better and persist longer in the niche when in the presence of larvae. We further found that larvae secrete a complex blend of metabolites, including N-acetyl-glucosamine (NAG), which act in synergy to support the long-term persistence of LpWJL in the shared habitat, and consequently maintain symbiosis. In parallel, we show that constant association between Drosophila and LpWJL is required for maximum growth benefit for Drosophila larvae. Thus, our study unravels an elegant farming mechanism by which an animal actively cultivates a mutually beneficial partnership with its bacterial symbiont through facultative nutritional symbiosis. This mode of symbiosis ensures fitness gains for both partners while facing poor dietary conditions.

Results

L. plantarum Occupies the Endoperitrophic Space, and Live Bacterial Cells Are Concentrated Anteriorly to the Midgut Acidic Region

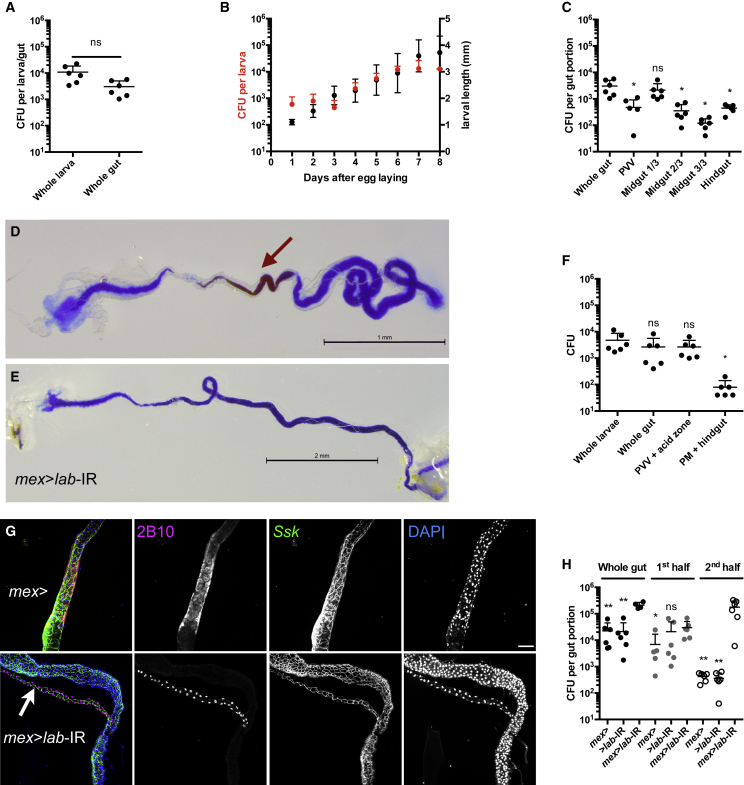

We previously identified LpWJL as a symbiotic bacteria associated with Drosophila during its entire life cycle, and promoting the growth of undernourished Drosophila larvae (Storelli et al., 2011). LpWJL is mostly found in the gut (Figure 1A), and its load increases steadily as the larvae grow (Figure 1B). To analyze in detail LpWJL localization in the larval gut, we quantified LpWJL's loads in different regions of the intestine (Figure S1). Viable LpWJL cells are present all along the intestinal tract, but the anterior part of the midgut harbors 10–100 more bacteria than the middle or posterior midgut sections (Figures 1C and S1A). While the pH in most parts of the midgut is neutral and the posterior-most part is alkaline, the middle section of the larval midgut encompasses the copper cells region, which is marked by luminal acidic pH (Figure 1D) (Overend et al., 2016, Shanbhag and Tripathi, 2009). We hypothesized that this acidic region forms a biological barrier regionalizing LpWJL accumulation in the gut. Accordingly, when we quantified the number of live LpWJL cells in two dissected gut sections delimited by the acidic region (Figures 1F and S1B), we found that live LpWJL cells accumulate in the anterior section that includes the proventriculus, the ventriculus, and the copper cell region. More than 95% of viable LpWJL cells were found in this section (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Viable L. plantarum Cells Accumulate Anteriorly to the Midgut Acidic Region

(A) Bacterial loads of surface-sterilized larvae and dissected guts after 6 days of mono-association with LpWJL on PYD.

(B) Larva bacterial loads (red closed circles) and larva longitudinal length (black closed circles) over time after mono-association on PYD.

(C) Bacterial loads of whole gut and dissected gut portions from 6DAEL mono-associated larvae. PVV, proventriculus and ventriculus. Midgut 1/3: first third of the midgut, minus the ventriculus. See Figure S1. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with whole-gut values.

(D and E) Representative guts of 2-day-old wild-type larva (y,w) (D) or 3-day-old mex>lab-IR larva (E) reared on rich yeast diet (RYD) supplemented with bromophenol blue (BB). The brown arrow points to the acidic region, which is missing in mex>lab-IR larva. Scale bars, 1 mm (D) and 2 mm (E).

(F) Bacterial load of dissected gut portions from larvae reared on PYD-BB diet. PVV + acid zone, proventriculus, ventriculus, anterior midgut, and the acidic zone. PM + hindgut, posterior midgut + hindgut.

(G) Knockdown of labial expression in the midgut prevents the differentiation of the copper cells. Control mex-Gal4; + larvae (top panel, mex>) and mex-GAL4; UAS-lab-IR acidic zone depleted larvae (lower panel, mex>lab-IR) stained with 2B10 monoclonal antibody highlighting the copper cell region, anti-Ssk marking midgut septate junction and DAPI for nuclei. The 2B10 antibody stains nuclei in Malpighian tubules (white arrow) and the cytoplasm of copper cells. The latter stain is missing in guts of mex>lab-IR larvae. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(H) Bacterial load of whole guts and gut portions of 7DAEL mex-Gal4>, >lab-IR and mex>lab-IR larvae reared on PYD-BB. Black dots, whole guts; dark gray dots, gut portions including PVV and the acid zone (for mex-Gal4 and UAS-lab-IR larvae) or approximate first half of the gut (for mex>lab-IR larvae). Open white dots, gut portions from the end of the acid region to the middle of the hindgut (for mex-Gal4 and UAS-lab-IR larvae) or the second half of the gut (mex>lab-IR larvae). Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference with the respective mex>lab-IR guts/gut portions. ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.05).

The copper cells are functionally and morphologically analogous to the acid-producing gastric parietal cells of the mammalian stomach (Dubreuil, 2004). labial is a homeotic gene that specifies and maintains the larval copper cell fate in the embryonic and post-embryonic tissue (Hoppler and Bienz, 1994). By lowering the expression of labial in the larval midgut through midgut-specific RNAi (mex-GAL4>UAS-labial-IR), we altered the larval acidic region. Specifically, the pH in this region is raised (Figure 1E), and 2B10 monoclonal antibody stain, a specific cytoplasmic marker of copper cell fate, disappeared (Strand and Micchelli, 2011) (Figure 1G). In these “acid-less” guts, LpWJL load is increased approximately 10 times compared with control guts (Figure 1H). Furthermore, 100 times more viable LpWJL cells are found in the posterior midgut region next to the would-be acidic domain, compared with control guts (Figures 1H, S1B, and S1C). Based on these observations, we conclude that, under physiological conditions, most viable LpWJL cells are found in the larval gut between the ventriculus and the middle midgut, and that the acidic region acts as a biological barrier shaping LpWJL distribution in the intestines.

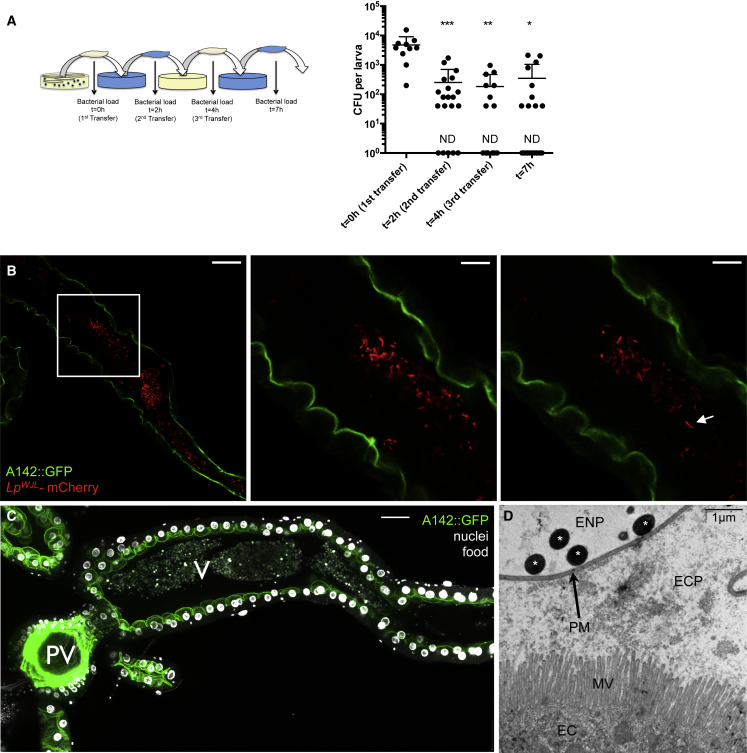

In adult Drosophila, commensal bacteria are transiently associated with their host (Blum et al., 2013, Broderick et al., 2014). Since the presence of LpWJL is highly regionalized in the larval gut, we wondered if LpWJL persists there or only transits through, in association with ingested food. To answer this question, we designed experiments to “pulse-chase” gut-associated bacteria. We transferred surface-sterilized third-instar larvae previously grown on bacteria-associated diet onto fresh axenic food, and transferred them again twice, at 2-hr intervals. We measured gut bacterial loads at each step (Figure 2A). Two hours after the first transfer onto axenic food, the mono-associated larvae have lost 95% of the viable LpWJL cells that they initially carried at the beginning of the experiment. In fact, a quarter of sampled larvae harbored no detectable colony-forming units (CFUs) (n = 5/20). This observation holds true at the second and third transfers (n = 6/14 and n = 8/18, respectively). This demonstrates that LpWJL cells do not persist in larvae, as they can be completely lost upon ingestion of new axenic food and excretion of previous gut content.

Figure 2.

L. plantarum Transits in the Endoperitrophic Space with the Food Bolus

(A) Evolution of the larval bacterial load after repeated transfers on axenic food. Left panel: experimental setup. Right panel: bacterial load quantification. To plot all data points on a log scale, a value of “1” was attributed to samples with no detectable CFUs and these have been marked “ND” (not detected). Asterisks represent a statistically significant difference with the initial bacterial burden (t = 0 hr).

(B) Ingested bacteria occupy the central part of the gut lumen. Anterior midgut of an A142::GFP larva fed on food containing LpWJL expressing mCherry. GFP localizes to the brush border and thus the apical side of the enterocytes. Individual mCherry-expressing bacteria or pairs of bacilli (arrow) can be seen in the lumen. The samples were mounted unfixed. Single confocal sections are shown. Images for the center and right panels were taken at higher magnification (zoom 3×) than for the left panels (white square) and they are distinct sections of one z stack. Scale bars, 50 μm (left), 16.67 μm (center and right).

(C) A142::GFP gut fixed and stained with DAPI to mark nuclei. Autofluorescence highlights the food bolus. PV, the proventriculus; V, the ventriculus. Scale bars, 50 μm (B and C). Note the apparent gap between the larval tissue (enterocyte epithelium) and the mass of fluorescent bacteria or food, both seem to occupy the endoperitrophic space.

(D) Transmission electron microscopy of anterior midgut transversal sections of 6DAEL LpWJL-mono-associated larvae reared on PYD. White asterisks, bacteria; PM, peritrophic matrix; ECP, ectoperitrophic space; ENP, endoperitrophic space; MV, microvilli; EC, enterocyte. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Asterisks represent a statistically significant difference with the initial bacterial burden (t = 0 hr): ∗∗∗0.0001 < p < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

We next studied the localization of LpWJL cells in the anterior midgut. To this end, we engineered a fluorescent LpWJL strain, and associated it with larvae expressing A142::GFP, an enterocyte brush-border marker (Buchon et al., 2013b). LpWJL cells expressing mCherry localize exclusively with food in the luminal compartment and are physically separated from the enterocytes (Figures 2B and S2A–S2D). The Drosophila midgut harbors a chitinous matrix called the peritrophic membrane, which wraps around the ingested food and protects the epithelium from mechanical, chemical, and microbial insults (Figure 2D) (Lemaitre and Miguel-Aliaga, 2013). Confocal microscopy analysis suggests that LpWJL cells may be secluded within the peritrophic membrane, in the endoperitrophic space (Figures 2B and 2C). To confirm this, we analyzed the anterior region of LpWJL mono-associated midguts by transmission electron microscopy and detected LpWJL cells exclusively in the endoperitrophic space of the luminal compartment (Figure 2D), indicating that LpWJL cells remain associated with the alimentary bolus in the intestinal lumen.

Stable Drosophila/L. plantarum Symbiosis by Constant Ingestion and/or Re-ingestion

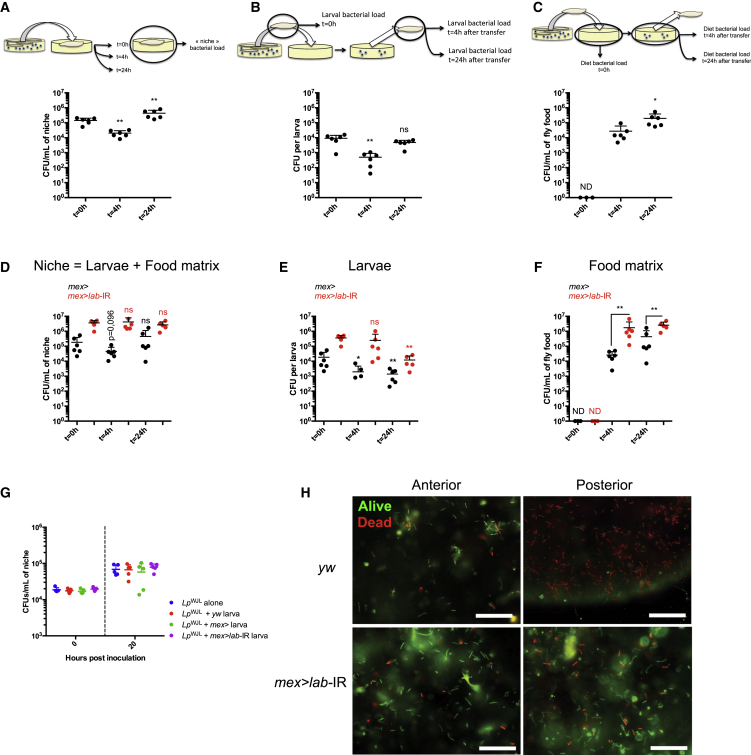

Despite the transient nature of the association between Drosophila and LpWJL, we observed that the internal bacterial loads of mono-associated larvae constantly increased during development (Figure 1B), therefore LpWJL cells must be continuously re-associated with larvae, probably by constant ingestion of contaminated food. To test this hypothesis, we surface-sterilized LpWJL mono-associated third-instar larvae and transferred them individually into tubes containing fresh axenic food. At 0, 4, and 24 hr post-transfer, we quantified the bacterial load of the entire niche (i.e., the food matrix plus the larvae dwelling on it), the larvae (removed from the food), and the food matrix (from which the larvae had been removed) (Figures 3A–3C). In this setup, the only bacteria introduced into the fresh niche at 0 hr are those carried in the guts of transferred larvae. We first observed a significant decrease of the bacterial number in the entire niche 4 hr post-transfer, when >90% of LpWJL cells present at 0 hr were eliminated (Figure 3A). However, the niche load rebounded dramatically within the next 20 hr and reached a number beyond the initial bacterial burden carried by the larvae. Consistent with the data presented in Figure 2A, we also observed an initial sharp decrease in LpWJL loads in individual larvae 4 hr post-transfer (Figure 3B). Importantly, bacteria could be recovered in the previously axenic food matrix at the same time point, showing that larvae release live LpWJL onto the food (Figure 3C). Interestingly, an increase in the bacterial load in the food and in the larvae was readily detectable in the next 20 hr (Figures 3B and 3C). This indicates that, while many bacterial cells die while transiting in the gut, the bacteria released alive by larvae can proliferate on the food matrix and gradually colonize it. These bacteria could then be re-ingested by larvae.

Figure 3.

Stable Drosophila/L. plantarum Symbiosis by Constant Reingestion

(A–C) Evolution of bacterial load after larvae transfer on axenic food. Upper panels: experimental setup. Lower panels: individual bacterial loads. Single 7DAEL mono-associated larvae were transferred on axenic PYD and the niche (food + larva) (A), the larval (B), or the food matrix (C). Bacterial loads were processed immediately (t = 0 hr) or at t = 4 hr and t = 24 hr post-transfer. Asterisks represent a statistically significant difference with initial burden, at the time of transfer (t = 0 hr) (A and B) or between the food matrix bacterial burden at t = 4 hr and t = 24 hr post-transfer (C). To plot all data points on a log scale, a value of “1” was attributed to samples with no detectable CFU and these have been marked “ND” (not detected).

(D–F) Evolution of bacterial loads after transfer of mono-associated larvae with guts depleted of their acidic region. Single mono-associated larvae from mex> (black dots) and mex>lab-IR genotypes (red dots) were transferred on axenic food, and substrate and larvae were processed independently, immediately (t = 0 hr) or at t = 4 hr and t = 24 hr post-transfer. The niche bacterial load (D) was calculated by adding larval load values (E) to the associated substrate load values (F). In (D), lettering above dot plots represent statistically significant differences between the niche burden at a given time point and the initial niche burden at the time of transfer (t = 0 hr) obtained with larvae of the same genotype (black asterisks for mex> niches and red asterisks for mex>lab-IR niches). The initial niche burden is considered as equal to the initial larval load since the food is axenic before larva transfer. In (E), asterisks represent statistically significant differences between the larval bacterial load at a given time point and the bacterial burden at the time of transfer (t = 0 hr) of larvae of the same genotype (black asterisks for mex> larvae and red asterisks for mex>lab-IR larvae). In (F), asterisks represent statistically significant differences between the bacterial loads of food matrixes having hosted mex> and mex>lab-IR larvae at t = 4 hr and t = 24 hr post-transfer.

(G) Bacterial load after 20 hr incubation of PYD initially inoculated with 104 CFU/mL of LpWJL alone or in presence of a single y,w mex> or mex>lab-IR larva.

(H) Live/dead bacteria stain in the endoperitrophic compartment, in different gut portions. Upper panels: stain in control (yw) animals. Lower panels: stain in animals devoid of copper cells (mex>lab-IR). Left panels show stain in portions of the midgut anterior to the copper cells region (Anterior). Right panels show stain in posterior parts of the midgut (Posterior). Live bacteria stain green, dead bacteria stain red. Scale bars, 30 μm. Note that while bacteria are dead in the posterior part of the gut of control animals, they are not completely lysed: they are efficiently stained by the dye, and their coarse morphology is not altered.

Asterisks illustrate statistical significance between conditions: ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.1). The p value is indicated when approaching statistical significance (0.05 < p < 0.1).

Since the midgut acidic region acts as a biological barrier shaping LpWJL accumulation and distribution in the midgut (Figure 1H), we wondered if the acidic region eliminates some of the LpWJL cells when they transit through the gut, thus explaining the drop in the bacterial load in the niche upon larvae transfer onto axenic food (Figure 3A). To address this question, we surface-sterilized and transferred larvae lacking the acidic region ("acid-less" larvae, mex>lab-IR) associated with LpWJL onto new axenic food and monitored the bacterial load of the entire niche (Figure 3D), the transferred larvae (Figure 3E), or the food matrix (Figure 3F) 4 and 24 hr post larvae transfer. In contrast to the control larvae, LpWJL load remained constant in the niche colonized by larvae with acid-less guts (Figure 3D). In addition, the decrease in LpWJL loads in acid-less larvae is delayed compared with mex> controls at 4 hr post-transfer (Figure 3E). One explanation could be that acid-less larvae need more time to purge the initially higher bacterial burden held in their guts (Figure 1H). However, mex> and acid-less larvae do not show a rebound in gut bacterial load 24 hr after transfer, as observed with yw larvae (Figure 3B). Thus, besides the function of copper cells, we cannot rule out the implication of physiological features that could vary between genotypes, such as ingestion and defecation rates, in modulating the evolution of gut bacterial load after transfer on a fresh axenic substrate. Finally, we did not detect differences in bacterial proliferation rates in the niche in a 20 hr period when larvae of the different genotypes, with or without copper cells, were present and when the initial bacterial inoculum was kept identical among conditions (Figure 3G). Therefore, the initial bacterial inoculum (or the quantity of bacteria defecated alive by larvae on a fresh susbtrate) is the main parameter dictating the evolution of the bacterial population in the niche in a 20 hr period. This demonstrates that the higher number of bacterial cells found alive on the food matrix 4 hr post-transfer of monoassociated acid-less larvae is directly responsible for the higher titer observed at 24 hr post-transfer (Figure 3F). These results indicate that removing the acidic region in the host's midgut preserves more live LpWJL cells during gut transit and, as a consequence, the excretion of LpWJL cells onto the food matrix is increased and substrate colonization is accelerated.

To refine our analysis, we used live/dead bacteria stains to probe bacterial survival throughout the intestine. In control animals, while most bacteria are alive in a portion anterior to the copper cells region, they are dead in a more posterior gut portion (Figure 3H, upper panels). This clear live/dead distribution is lost in animals devoid of copper cells, as most bacteria are alive throughout the midgut (Figure 3H, lower panels). Thus, most bacteria are killed when they transit through the acidic region of the gut.

Collectively, our results demonstrate that Drosophila and LpWJL maintain a stable symbiosis through a reiterated cycle: ingestion of LpWJL cells by larvae, which transit with food through the midgut; while a major portion of the bacteria are killed in the acidic region, the surviving LpWJL cells are excreted by larvae and can repopulate the food matrix before being re-ingested.

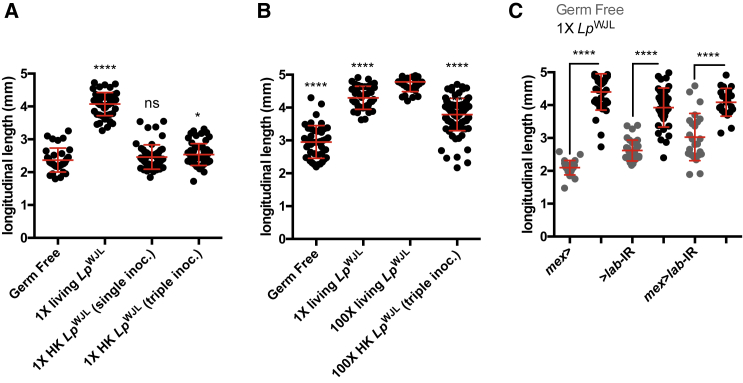

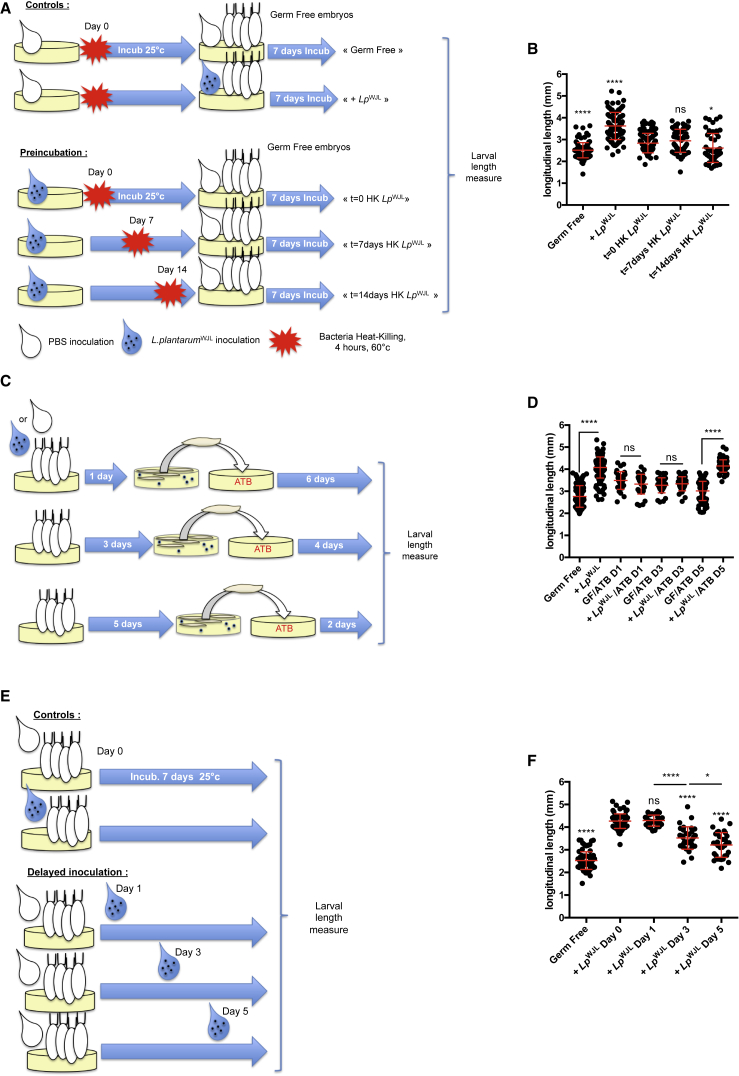

L. plantarum Has to Be Alive and Constantly Associated with Larvae to Sustain Drosophila Growth

The question arises whether dead LpWJL cells may be digested and become an additional food source that is sufficient to promote larval growth upon undernutrition. First, even though bacteria are killed during their transit through the acidic region, they are not completely lysed: they can be visualized with live/dead stains and their coarse morphology does not seem altered (Figure 3H). To further challenge the hypothesis that dead bacterial cell constituents contribute to larval growth, we added, once or repeatedly, heat-killed LpWJL cells to axenic diets containing freshly laid GF eggs. We then assessed larval growth by quantifying the length of the associated larvae at day 7 (D7) after egg laying (AEL) as described previously (Erkosar et al., 2015). Strikingly, the larvae once- or thrice-inoculated with dead LpWJL cells did not grow more than GF siblings (Figure 4A). We detected an increase in larval growth when GF larvae were repeatedly inoculated with 100× dead LpWJL cells, yet the larvae once inoculated with the same amount of viable LpWJL cells still grew longer (Figure 4B). These results clearly demonstrate that, unless in massive excess, dead LpWJL cells fail to promote larval growth to the extent of live bacteria.

Figure 4.

L. plantarum Has to Be Alive to Express Its Full Potential to Sustain Drosophila Growth

(A and B) Larval longitudinal length at D7 AEL after dead/live bacteria inoculation on PYD. Live bacteria (1× living LpWJL or 100× living LpWJL) were inoculated once at D0 AEL. Heat-killed (HK) bacteria (1× HK LpWJL or 100× HK LpWJL) were inoculated once (single inoc., at D0 AEL) or three times (triple inoc., at D0, D3, and D5 AEL). (A) Asterisks represent statistically significant differences with GF larvae. (B) Asterisks above dot plots represent statistically significant differences with larvae inoculated once with 100× living LpWJL.

(C) Larval longitudinal length at D7 AEL of mex-GAL4 (mex>), UAS-labial-IR (>lab-IR) and mex-GAL4/UAS-lab-IR (mex>lab-IR) animals after bacterial association on PYD. Gray dot plots represent measurements of GF larvae; black dot plots represent measurements of mono-associated larvae. Asterisks represent statistically significant difference between GF and mono-associated larvae from the same genotype.

Asterisks illustrate statistical significance between conditions: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.1).

In parallel, we tested the growth performance of the acid-less larvae, in which midgut inactivation of LpWJL cells is greatly impaired (Figure 1H). In these animals, LpWJL-mediated growth promotion is still strongly detected (Figure 4C). Therefore, LpWJL inactivation in the midgut is not required for LpWJL-mediated growth promotion, and even though constituents of dead bacteria may serve as a limited trophic source, it is not sufficient to explain the maximum growth benefit that live LpWJL provides to its animal partner in a low nutritional condition. In conclusion, our results establish that LpWJL cells have to be alive and presumably metabolically active to express their full potential to sustain larval growth.

Previous studies suggest that commensal bacteria can confer increased metabolic fitness to Drosophila adults through direct modification of the food (Chaston et al., 2014, Huang and Douglas, 2015). We thus tested if diet modification by LpWJL confers larval growth benefit. To this end, we pre-incubated the diet with LpWJL for different lengths of time (0, 7, or 14 days) followed by a mild heat treatment (60°C for 4 hr) that is sufficient to completely kill LpWJL in this setting (data not shown). We then seeded GF embryos onto the “modified” diet (Figure 5A). We found that such pre-inoculation of the diet with LpWJL barely promoted growth of GF larvae; in fact, the longest incubation period even hampered growth (Figure 5B). We then tested if the constant association between Drosophila and LpWJL cells is necessary to sustain LpWJL-mediated larval growth promotion. We also wished to define if there is a critical period during larval development when such association is needed for maximal growth gain. To this end, we did the following two experiments: we associated GF embryos with LpWJL and transferred the mono-associated larvae at different time points onto food containing a cocktail of antibiotics that efficiently depletes LpWJL from the niche (Figure 5C and data not shown). In parallel, we mono-associated GF individuals with LpWJL at different time points during larval development (Figure 5E). Removing LpWJL from the niche with antibiotics at D1 or D3 markedly diminished LpWJL-mediated larval growth promotion, while removal on D5 resulted in a partial (if any) alteration of LpWJL-mediated larval growth promotion (Figure 5D). Moreover, varying the duration of LpWJL association to GF animals yielded consistent result: the earlier the inoculation, the more visible the LpWJL-mediated enhanced growth phenotype (Figure 5F). Taken together, our results demonstrate that to express its full benefit toward juvenile growth, LpWJL has to be alive and constantly provided to its partner.

Figure 5.

Constant Association Is Necessary for L. plantarum-Mediated Drosophila Growth

(A) Experimental setup to assess the impact of diet pre-incubation with bacteria on larval growth.

(B) Larval longitudinal length at D7 AEL after rearing on pre-incubated diets. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences with the pool of larvae reared on PYD where bacteria were immediately killed after inoculation (t = 0 HK LpWJL).

(C) Experimental setup to assess the impact of the timing of bacterial ablation on larval length gain after mono-association.

(D) Larval longitudinal length at D7 AEL after transfer on ATB-containing PYD. Efficient bacterial inactivation by ATB was assessed by plating larval homogenates at the time of collection on Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar plates. Larval bacterial loads were evaluated to 0 CFU per larva for +LpWJL/ATB D1 and +LpWJL/ATB D3 and 19.3 CFU/larva for +LpWJL/ATB D5. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between GF and mono-associated larvae pools transferred at the same time on ATB-containing PYD.

(E) Experimental setup to assess the impact of delayed mono-association on larval length gain.

(F) Larval longitudinal length at D7 AEL on PYD. Axenic embryos were mono-associated following the standard procedure (+LpWJL D0), or mono-association was delayed (D1, D3, and D5 AEL). Asterisks represent statistically significant differences with the pool of larvae mono-associated at D0 AEL. Asterisks above horizontal bars represent statistically significant differences between two conditions.

Asterisks illustrate statistical significance between conditions: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.1).

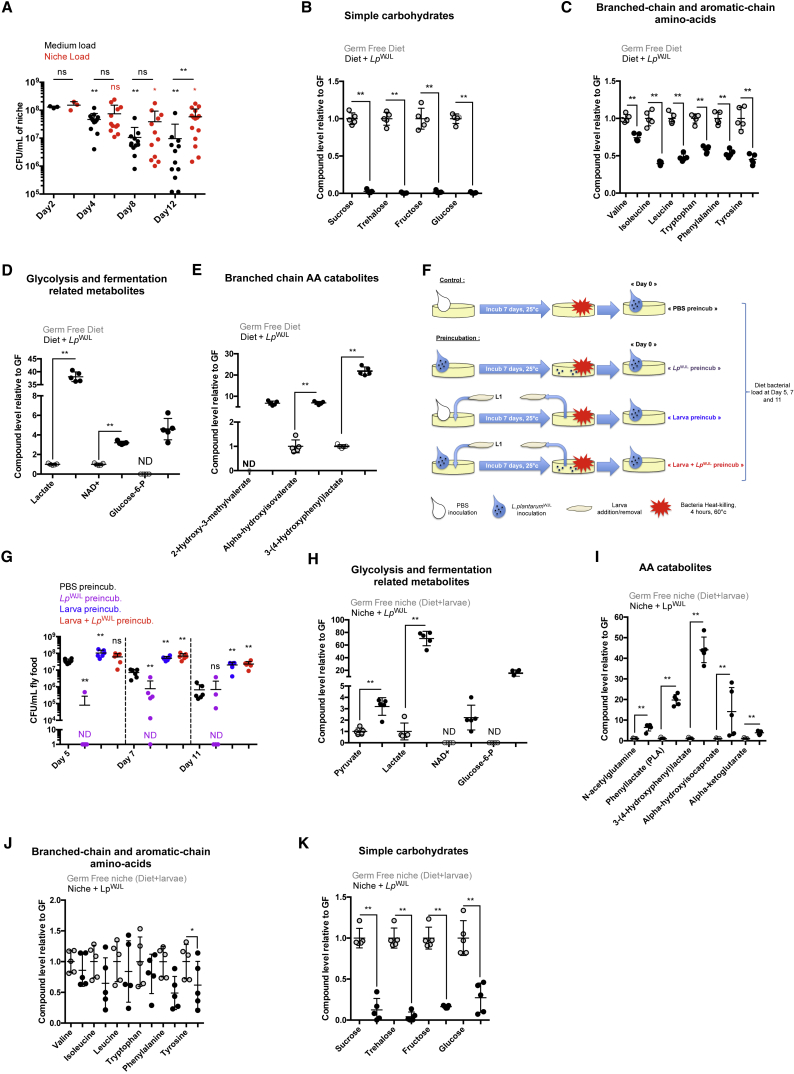

Drosophila Larvae Sustain L. plantarum Long-Term Maintenance in Their Shared Niche

The benefit of LpWJL to Drosophila growth performance upon chronic undernutrition is well established (Erkosar et al., 2015, Storelli et al., 2011). We now show that this beneficial partnership relies on constant association, probably through constant larval feeding activity (Figure 5). Importantly, we have identified a cost to LpWJL during symbiosis with Drosophila, as the majority of the ingested bacteria are killed while transiting through the gut. This observation raises the question whether such symbiosis is actually mutualistic. We thus evaluated how this cost impacts bacterial fitness in the niche in the long term. To this end, we measured the evolution of bacterial titers (CFU counts) in the food matrix over a defined period of time, in the presence or absence of larvae. Specifically, we inoculated 108 LpWJL CFUs/mL onto axenic food and followed the titers over a period of 12 days (larvae enter metamorphosis around days 8–10 AEL). In the absence of larvae, we observed that LpWJL titers maintain at a plateau at around 108 CFUs/mL of fly food until D2 post-inoculation and markedly decrease by about 1–2 logs in the following days (Figure 6A). In contrast, when larvae are present, LpWJL titers maintain the same plateau over the 12 days (Figure 6A). These observations establish that Drosophila and LpWJL engage in a reciprocal long-term beneficial association whereby larvae presence sustains higher titers of LpWJL in the niche, despite death of many bacteria cells during the intestinal transit.

Figure 6.

Presence of Drosophila Larvae Spares Essential Nutrients and Fortifies the Diet Ensuring L. plantarum Growth and Maintenance

(A) Quantification of niche (red dots) and food matrix (black dots) bacterial loads along time. Niches and food matrixes were processed at D2, D4, D8, and D12 post-inoculation/larval addition for bacterial load quantification. Asterisks just above the dot plots represent statistically significant differences between substrate (black asterisks) or niche (red asterisks) bacterial load at a given time point, and the bacterial load of respective substrate or niche at D2 post-inoculation. Asterisks above horizontal bars represent statistically significant differences between niche and substrate bacterial load at the same time point.

(B–E) Graphs representing the relative levels of metabolites in the diet incubated for 3 days with LpWJL compared with axenic diet (GF). Open circles represent the GF samples, black closed circles the LpWJL inoculated samples. Metabolites not detected in one condition (samples falling below the compound's detection threshold) are marked with ND (not detected). Asterisks illustrate statistically significant difference between conditions.

(F and G) Effect of food matrix pre-incubation with bacteria, larvae, or bacteria + larva on bacterial titer evolution after re-inoculation. (F) Experimental setup. As parallel controls, pools of n = 3 food matrixes pre-incubated with PBS, bacteria, larva, and bacteria + larva were re-inoculated with PBS after aseptic larva removal and heat treatment, and incubated for 11 days at 25°C before crushing and plating on MRS agar plates. No colony was found on MRS agar plates, confirming efficient bacterial inactivation by the heat treatment. These controls are not illustrated in the scheme of the experimental setup for the sake of clarity. (G) Quantification of food matrix bacterial load evolution after pre-incubation with PBS, bacteria, larvae or larvae + bacteria. Food matrixes were processed at D5, D7, and D11 post re-inoculation for bacterial load quantification. Black dots illustrate bacterial loads for PBS pre-incubated food matrixes, purple dots for food matrixes pre-incubated with bacteria, blue dots for food matrixes pre-incubated with GF larva, and red dots for food matrixes pre-incubated with both larva and bacteria. Vertical interrupted lines delineate values obtained for the different conditions at the same day. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences with the samples of food matrixes pre-incubated with PBS at the same day.

(H–K) Graphs representing the relative levels of metabolites in the niches incubated for 3 days with LpWJL compared with axenic niches (GF). Open circles represent the GF samples, black closed circles the LpWJL-inoculated samples. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions.

Asterisks above horizontal bars illustrate statistical significance between conditions: ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.1).

Presence of Drosophila Larvae Spares Essential Nutrients and Modifies the Diet Ensuring L. plantarum Maintenance in the Niche

Since LpWJL maintenance in the diet benefits from the presence of larvae, we reasoned that bacterial metabolism might be altered during symbiosis. To identify potential alterations of LpWJL metabolism upon symbiosis, we compared profiles of nutrients and metabolites present in axenic diet and diet inoculated with bacteria (Table S1). In the absence of larvae, LpWJL cells maintain a high titer for 2–4 days after inoculation and then plunge (Figure 6A, black dots). We therefore analyzed samples 3 days post LpWJL inoculation. Macronutrients such as simple sugars (sucrose, trehalose, fructose, and glucose) and most EAAs were depleted from the diet (Figures 6B and 6C). This depletion is accompanied by signatures of intense glycolytic activity, homolactic fermentation (increased glucose-6-phosphate, lactate and NAD+; Figure 6D), and catabolism of EAAs (increased 2-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate, α-hydroxyisovalerate, and 3,4-hydroxyphenyl lactate; Figure 6E). To see if macronutrient depletion directly impacts the maintenance of LpWJL cells, we inoculated LpWJL cells onto axenic diets, incubated them for 7 days, heat killed them, re-inoculated the modified (spent) diet with fresh LpWJL cells and followed the LpWJL titers over time (Figures 6F and 6G). The fresh LpWJL population performed poorly on the LpWJL pre-incubated diet, while it performed optimally on an unspent diet (Figure 6G, black versus purple). In summary, when inoculated alone onto the poor yeast diet, LpWJL cells deplete essential nutrients, including simple sugars and EAAs. Nutrient depletion then likely triggers a reduction in LpWJL titers over time.

To study the bacterial metabolic activity in symbiosis, we next profiled metabolites of the niche, i.e., the food containing Drosophila larvae with or without LpWJL inoculation (Table S2; Figures 6H–6K). Interestingly, we again detected clear signatures of heightened glycolytic activity and homolactic fermentation (Figure 6H), along with EAA catabolism (Figure 6I) in presence of bacteria, suggesting that the core metabolism of LpWJL cells is not altered upon symbiosis (compare Figures 6H and 6I with Figures 6D and 6E). Yet, the amounts of EAAs and simple sugars were spared (compare Figures 6B and 6C with Figures 6J and 6K). We thus hypothesized that Drosophila larvae modify the nutritional substrate, allowing its bacterial partner to sustain its core metabolic activity and maintenance on the diet. Consistent with this hypothesis, pre-incubation of the diet with GF larvae improved maintenance of LpWJL CFUs (Figures 6F and 6G, black versus blue). Moreover, incubation with both LpWJL and larvae (a condition that spares simple sugars and EAAs; Figures 6J and 6K), followed by removal of larvae and heat inactivation of LpWJL (Figure 6F), delivered a suitable substrate for the maintenance of fresh LpWJL upon re-inoculation (Figure 6G, black versus red). Based on these results, we reasoned that larvae, even when axenic, modify and/or fortify the diet in a way that it becomes more suitable for LpWJL long-term maintenance.

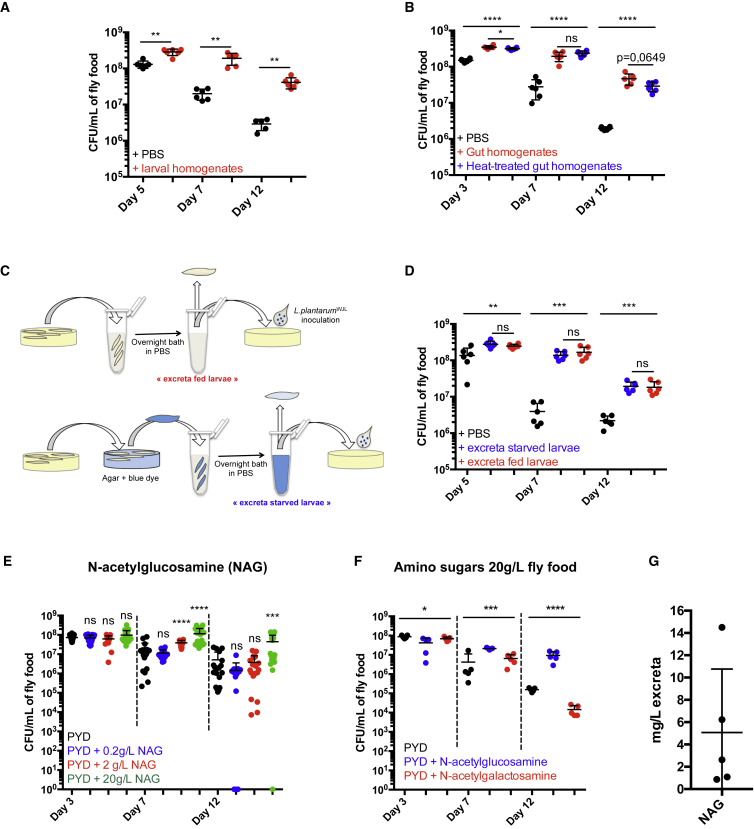

Drosophila Intestinal Excreta Fortifies the Diet and Ensures L. plantarum Long-Term Maintenance in the Niche

Drosophila larvae utilize nutrients from the diet to sustain their own growth, making it a likely competitor of LpWJL on the poor yeast diet. Yet, larval presence in the niche benefits the long-term maintenance of bacteria. Proteins and starch are the major macronutrients in our experimental diet, and a recent genomic survey implies that necessary enzymes required for the processing and utilization of long polypeptides and starch are lacking in LpWJL (Martino et al., 2016). Drosophila enterocytes express several intestinal digestive enzymes including peptidases and amylases, which may fulfill the proposed processing activities (Lemaitre and Miguel-Aliaga, 2013). It is conceivable that the digestive activities of the larvae help LpWJL persist in the niche. However, we found no accumulation of starch degradation products, such as maltose, while comparing the metabolites and nutrients of axenic diets versus diets containing larvae (i.e., germ-free niches) (Table S2), and amynull larvae, which lack amylase activity (Hickey et al., 1988), promote LpWJL long-term maintenance in the niche as well as control larvae (Figure S3A). Therefore, starch digestion by Drosophila larvae is unlikely to be implicated in the bacterial long-term maintenance during symbiosis. We next postulated that LpWJL may benefit from larval proteolytic activities, as they would break down dietary proteins, rendering small peptides and amino acids accessible to LpWJL cells. We thus altered the capacity of Drosophila larvae to process dietary proteins by adding to the diet a cocktail of protease inhibitors (PICs). PIC addition to the diet has a dramatic negative impact on larval growth dynamics (Figure S3B) (Erkosar et al., 2015). Yet, it only marginally affects LpWJL maintenance in the niche: even though niche titer is significantly lower at D12 in the presence of PIC, the beneficial effect of larval presence on bacterial maintenance is still observed (compare “Food matrix” and “Niche + Proteases Inhibitor” conditions in Figure S3C). Thus, processing of dietary starch and proteins by Drosophila larvae does not seem to be strictly required to maintain LpWJL on the diet in the long run.

Next, we reasoned that the diet is fortified with metabolites or nutrients of larval origin that can sustain the long-term maintenance of LpWJL cells. Consistently, supplementing axenic diets with GF larvae homogenates promoted long-term maintenance of LpWJL (Figure 7A). In addition, supplementing diets with heat-treated GF larvae gut homogenates recapitulates this effect (Figure 7B). Thus, one or multiple non-enzymatic compound(s) of intestinal origin are required for LpWJL maintenance. To further refine our analyses, we fortified diets with larval intestinal excreta. To do so, we bathed larvae overnight in PBS to purge them from their intestinal content (Figures 7C and S3D–S3F). Fortifying diets with intestinal excreta collected from fed or starved larvae favors LpWJL long-term maintenance on the diet (Figures 7D and S3D–S3F). As a control, a solution collected after bathing dead larvae overnight in PBS failed to promote bacterial maintenance (Figure S3G).

Figure 7.

Drosophila Intestinal Excreta and N-Acetyl-Glucosamine Maintains L. plantarum in the Niche

(A) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load over time after bacteria co-inoculation with PBS (black dots) or heat-treated larval homogenates (red dots).

(B) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load over time after bacteria co-inoculation with PBS (black dots), gut homogenates (red dots), or heat-treated gut homogenates (blue dots).

(C and D) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load over time after bacteria co-inoculation with larval excreta. (C) Experimental setup. For controls and more detailed information, see Figure S3 and the STAR Methods. (D) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load after bacteria co-inoculation with larval excreta collected from fed larvae (red dots) or from starved larvae (blue dots).

(E) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load over time, on substrate supplemented with various concentrations of N-acetyl-glucosamine (NAG). NAG was added at concentrations of 0.2 (blue), 2 (red), and 20 g/L (green) fly food.

(F) Evolution of food matrix bacterial load on substrate supplemented with the amino sugars NAG (blue dot) and N-acetyl-galactosamine (red dots). Amino sugars were supplied independently at a concentration of 20 g/L in the fly food. As controls, bacteria were incubated on PYD (black dots).

(G) Quantification of NAG in the excreta of starved larvae by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗∗∗0.0001 < p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. ns, not significant (p > 0.1).

Asterisks above horizontal bars illustrate statistical significance between conditions: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗0.0001 < p < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, ns, not significant (p > 0.1). The exact p value is indicated when approaching statistical significance (0.05 < p < 0.1).

Collectively our observations indicate that the intestinal excreta of larvae are sufficient to sustain bacterial maintenance, and that this effect is not explained by the supply of non-assimilated dietary nutrients contained in larval feces. In addition, heat-treating intestinal excreta only slightly reduces their ability to sustain bacterial presence in the niche (Figure S3H), indicating again that this beneficial effect does not rely on the supply of larval digestive capabilities. Therefore, we postulated that one or multiple compounds, which we refer to as "maintenance factors,” are shed by larval intestines and fortify the axenic diet leading to long-term maintenance of LpWJL in the niche.

The Effect of Drosophila Intestinal Excreta on L. plantarum Long-Term Maintenance Is Mediated by Multiple Maintenance Factors, Including N-Acetyl-glucosamine

To further characterize these maintenance factors, we performed a metabolite profiling of live or dead larva excreta (Table S3). We focused on compounds enriched in the excreta of live larvae, and further rationalized our candidate approach by selecting families of compounds that may influence the long-term maintenance of LpWJL (Figure S4A). To determine if one or more of these compounds sustains LpWJL long-term maintenance, we supplemented poor yeast diet (PYD) with the respective purified compounds, and scored bacterial maintenance. Supplementing diets with derivatives of purine metabolism does not improve maintenance of LpWJL over time (Figure S4B). The same observation is made for tryptophan derivatives (Figure S4C), xanthurenate even hastening bacterial titers decrease over time (Figure S4C, right panel). Next, we tested N-acetylated amino acids and formylmethionine in individual supplementations (Figure S4D). Most supplementations do not influence LpWJL titers over time, with the exceptions of N-acetyl-asparagine, -glutamine, -glutamate, -arginine, and -glycine. N-Acetylasparagine seems deleterious to the bacterial maintenance, while N-acetyl-glutamine and N-acetyl-glutamate, have a slight beneficial effect at D7 (lost at D12). In addition, N-acetylarginine and N-acetylglycine have a slight beneficial effect on bacterial titer at D12. We wondered whether supplying greater quantities of these four N-acetylated amino acids would amplify their beneficial effect on bacterial persistence. We therefore supplemented diets with 20 times more N-acetyl-glutamine, -glutamate, -arginine, and -glycine (Figure S4E). In this setting, we did not detect any beneficial effect of these compounds on the maintenance of LpWJL over time. Taken together, these results establish that N-acetyl- amino acids do not significantly impact bacterial persistence. Finally, we tested N-acetylated amino sugars supplementation. Our metabolic analysis was not able to distinguish between NAG and N-acetyl-galactosamine (Figure S4A). We thus supplemented PYD with these two N-acetylated amino sugars independently and checked their effect on bacterial persistence (Figures 7E and 7F). We found that NAG supplementation promotes bacterial persistence in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 7E and 7F). This effect is specific to this amino sugar, as supplementation with N-acetyl-galactosamine is ineffective (Figure 7F). We next checked if larval excreta indeed contains free NAG, and in which quantity. To this end, we submitted the excreta to high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (Figures S4F, S4G, and 7G). Free NAG was detected in the excreta of starved GF larvae, with an average concentration of 5 mg/L (Figure 7G). This concentration is 400–4,000 times lower than the one sufficient to promote bacterial persistence in our NAG supplementations assays (Figures 7E and 7F). Altogether, our results demonstrate that among all the candidate maintenance factors identified and tested, NAG is the only factor, which on its own is able to sustain bacterial persistence. However, it does so when supplemented in excess in the diet as compared with the concentration found the excreta. Adding NAG alone in a “physiological” concentration range is not sufficient to recapitulate the effect of the excreta. Thus, we posit that the maintenance effect of larval excreta is due to a complex blend of factors, including NAG, acting together to ensure bacterial long-term bacteria persistence.

Discussion

The use of animal models in an integrative research framework has recently gained traction to study the interactions between microbiota and animal physiology (Leulier et al., 2017). Within this framework, the Drosophila model offers unique advantages to shed light on fundamental concepts and characterize the mechanisms involved in animal-commensal bacteria interactions (Erkosar et al., 2013, Lee and Brey, 2013, Ma et al., 2015, Strigini and Leulier, 2016). Until now, the exact mode of association between Drosophila and its commensal microbes remain unclear.

Our work demonstrates that there is no long-term bacterial residency in the larval gut: ingestion of axenic food can wipe all traces of symbionts. Therefore, Drosophila/LpWJL association is transient by nature. The larva itself renders the delicate balance of the association more precarious as it actively kills its commensals. This may appear paradoxical, as constant association with live LpWJL is required to grant a maximum growth benefit to the larvae, but this paradox may reflect a strategy employed by Drosophila to preserve its own fitness. In the wild, Drosophila larvae feed on rotting fruits and ingest a large variety of microbes, including potential pathogens, over which they must keep a strict control. The Drosophila intestine possesses a defensive antimicrobial arsenal, which includes the production of antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species by enterocytes (Buchon et al., 2013a). The copper cells likely belong to this arsenal: indeed, their ablation in Drosophila adults carrying a diverse microbiota leads to premature aging and reduced lifespan, probably due to microbiota dysbiosis (Li et al., 2016). Therefore, the acidic pH of the copper cells region should more be seen as a selective defense mechanism against environmental micro-organisms sensitive to low pH, rather than a major part of the digestive process, as acid-less larvae grew normally in conditions where environmental microbes are strictly controlled. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the dominant families of Drosophila commensal bacteria are acid-generating bacteria such as Acetobacteraceae and Lactobacillaceae, which tolerate low pH. For these reasons, we do not consider Drosophila as a bona fide “host” for its symbionts, but rather as a “partner,” conveying and seeding its commensals into the entire nutritional niche, whether it is a rotting fruit in the wild or a food vial in the laboratory. This strategy allows Drosophila to get the most out of its association with its symbiotic bacteria at the lowest cost: while keeping a strict control over ingested microbes, it maintains the stability of its association with commensals through the continuous cycles of excretion, seeding of live bacteria, bacterial proliferation on the food, and re-ingestion.

A direct and constant association with live bacteria is required for maximal larval growth gain. Therefore, live bacteria probably elicit a specific response while transiting through the larval gut. In a previous study, we demonstrated that LpWJL induces the transcription of a set of intestinal peptidases, thus maximizing amino acid uptake and sustaining the activity of the nutrient-sensitive TOR signaling pathway (Erkosar et al., 2015, Storelli et al., 2011). Combining our previous and current findings, we propose a model whereby the continuous flow of ingested live LpWJL cells maintains constant peptidases activation, which favors optimal digestion of dietary proteins and amino acid uptake along larval development. This process would then sustain TOR pathway activity and higher larval growth rate. Consistent with this model, forced and continuous transcriptional activation of intestinal peptidases in GF animals partly recapitulates the effect of LpWJL on larval growth (Erkosar et al., 2015). The questions remain as to how bacteria sustain peptidases activation and why living bacteria are strictly required. We showed that peptidase activation in presence of LpWJL relies on the sensing of bacterial cell wall components (Erkosar et al., 2015, Matos et al., 2017). We propose that the constant release of cell wall fragments by live bacteria play a role in the transcriptional activation of these digestive enzymes, and in sustaining growth rates.

The advantages of Drosophila/LpWJL symbiosis may seem, at first sight, biased toward the animal partner. Even though a great fraction of ingested bacteria get killed while transiting through the larval gut, symbiosis asserts an overall beneficial effect for symbionts. In addition to spreading their commensals in the niche, larvae also ensure their long-term maintenance on the substrate. When alone in the food matrix, LpWJL cells rapidly consume essential nutrients until exhaustion, after which their titer drops. In contrast, upon symbiosis, LpWJL titer remains high for a longer period of time. We demonstrate that larvae excrete a complex blend of metabolites, among which NAG, supporting the long-term persistence of LpWJL in the shared habitat. We refer to these metabolites as “maintenance factors” and posit that they act as nutrients for symbionts, which could compensate for the exhaustion of nutritional resources in the substrate and subsequently delay population decay in the niche. Yet, the full complement of factors secreted by larvae required for bacterial maintenance, as well as their mode of action, remain elusive.

Drosophila/LpWJL symbiosis is facultative by nature. Both partners can exist without each other and symbiosis can be suddenly broken by the ingestion of axenic food (in the lab) or microbes incapable of coping with low pH. In this context, we propose that the flexibility of facultative nutritional mutualism contributes to the ecological success of species with nomadic lifestyles, and therefore changing and often scanty dietary sources. We can postulate that, in order to adopt such lifestyle, nomadic organisms must be able to adapt to various and fluctuating environments without relying on a fixed symbiotic relationship. L. plantarum is a highly versatile bacterial species, notably thanks to its vast metabolic repertoire (Martino et al., 2016). The flexible nature of its symbiosis with Drosophila (and probably other animals) may have helped retain this potential: keeping extensive metabolic capabilities would preserve Lp's aptitude to thrive in a variety of niches, with and without its animal partner. On the other hand, Drosophila larvae would benefit from Lp's ability to efficiently and rapidly colonize the shared niche, especially when excreted in minute amounts. The same reasoning is applicable to Drosophila: larvae feed on a variety of fruits, whose microbial composition and nutritional content can change upon maturation and decay. Consequently, Drosophila larvae can experience varying nutritional and microbial conditions depending on where and when eggs have been laid. Therefore, it is advantageous for the larvae not to strictly rely on specific symbionts' functionalities to survive fluctuating dietary conditions. In support of this idea, Lp (and probably other commensals) potentiates existing functions in Drosophila physiology to accelerate larval development on a poor diet, i.e., by enhancing larval gut peptidase activity (Erkosar et al., 2015, Matos et al., 2017). Therefore, Drosophila/Lp symbiosis represents a facultative nutritional mutualism paradigm that may apply to the symbioses between bacterial and animal species with nomadic lifestyles and changing dietary environments.

While a lot of attention has been dedicated to the taxonomic classification of symbiotic bacteria that modulate the physiology of their animal partner, or to the bacterial mechanisms granting physiological benefits to the host, little is known regarding the animal factors that impact bacterial fitness and that are potentially implicated in the perpetuation of animal-bacteria symbiosis. Exploring both sides of symbioses is necessary to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the interaction. A vast number of studies agree on the fact that dysbiosis and impoverishment of the microbiota by disease, diet, or antibiotic treatment are a threat to health (Blaser, 2016, Mondot et al., 2013, Sonnenburg et al., 2016). A more complete understanding of the mechanism of host/bacteria symbioses, and notably the animal factors favoring the growth and persistence of functionally important commensal phyla, would help in designing innovative dietary or prebiotic interventions aimed at maintaining or restoring symbiotic homeostasis. Using a model animal-commensal association upon chronic undernutrition, we now reveal that the animal partner farms its commensals with the secretion of maintenance factors that allow the perpetuation of their association. In parallel, symbionts are required to optimize extraction of dietary nutrients and sustain growth despite chronic undernutrition. Knowing that the phenomenon of commensal-mediated growth promotion is conserved in mammals (Schwarzer et al., 2016), our study paves the way to identify the evolutionary-conserved animal factors required to maintain symbiosis.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| 2B10 mouse monoclonal anti-Cut antibody | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | RRID: AB_528186 |

| Rabbit anti-Ssk antibody | Mikio Furuse (Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine) | N/A |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli: TG1 supE hsd5h thi (Δlac-proAB) F’ (traD36 proAB- lacZΔM15) | Baer et al., 1984 | N/A |

| L. plantarum: LpWJL | Ryu et al., 2008 | N/A |

| L. plantarum: LpWJL-GFP (L. plantarumWJL carrying pMEC276) | This paper | N/A |

| L. plantarum: LpWJL-mCherry (L. plantarumWJL carrying pMEC275) | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Inactivated Dried Yeast | Bio Springer | Springaline BA95/0-PW |

| Cornmeal | Westhove | Farigel maize H1 |

| Agar | VWR | #20768.361 |

| Methylparaben Sodium Salt | MERCK | ref. #106756 |

| Propionic Acid | CARLO ERBA | cref. #409553 |

| Bromophenol Blue sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | B5525-5G |

| Erioglaucine Disodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | 861146-5G |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | P2714 |

| Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) Broth Medium | Difco | ref. #288110 |

| Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) Agar Medium | Difco | ref. #288210 |

| N-Acetyl Glucosamine | Sigma-Aldrich | A8625 |

| N-Acetyl Galactosamine | Carl Roth | 4114.2 |

| Hypoxantine | Sigma-Aldrich | H9377 |

| Xanthine | Sigma-Aldrich | X7375-10G |

| Orotate | Sigma-Aldrich | O2750-10G |

| Kynurenate | Sigma-Aldrich | K3375-250MG |

| Tryptophan | Carl Roth | 1739.2 |

| Xanthurenate | Sigma-Aldrich | D120804-1G |

| N-Acetylserine | Sigma-Aldrich | A2638-1G |

| N-Acetylvaline | Sigma-Aldrich | 8.14599.0050 |

| N-Acetylglutamine | Sigma-Aldrich | A9125-25G |

| N-Acetylglutamate | Sigma-Aldrich | 855642-25G |

| N-Acetylasparagine | Sigma-Aldrich | 441554-1G |

| N-Acetylglycine | Sigma-Aldrich | A16300-5G |

| N-Acetylarginine | Sigma-Aldrich | A3133-5G |

| N-Acetylalanine | Sigma-Aldrich | A4625-1G |

| N-Acetylhistamine | Sigma-Aldrich | 858897-1G |

| N-Formylmethionine | Sigma-Aldrich | F3377-1G |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit | Invitrogen | L7007 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Metabolomic Dataset of Diet +/- L. plantarumWJL | This paper | Table S1 |

| Metabolomic Dataset of Niche +/- L. plantarumWJL | This paper | Table S2 |

| Metabolomic Dataset of Live/dead Larvae Excreta | This paper | Table S3 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. melanogaster: y,w (reference strain for this work) | N/A | |

| D. melanogaster: A142::GFP | Buchon et al., 2013b | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: mex-GAL4 (X chromosome insertion) | Phillips and Thomas, 2006 | N/A |

|

D. melanogaster: UAS-lab-IR y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8]=TRiP.JF02317}attP2/TM3, Sb[1] |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | 26753 |

| D. melanogaster: amynull (deletion of the amylase locus) | Hickey et al., 1988, Chng et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pNZ8148 plasmid: Cmr, Lactococcus lactis pSH71 replicon | MoBiTech | VS-ELV00200-01 |

| pMEC275 plasmid: pNZ8148 carrying mCherry cDNA codon-optimized for L. plantarum fused to the L. plantarum Pldh constitutive promoter (lactate dehydrogenase) | C.D., unpublished data | N/A |

| pMEC276 plasmid: pNZ8148 carrying GFP cDNA codon-optimized for L. plantarum fused to the L. plantarum Pldh constitutive promoter (lactate dehydrogenase) | C.D., unpublished data | N/A |

| L. plantarum codon-optimized mCherry and GFP genes | Eurogentec (Belgium) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | NIH Image | https://imagej.net/ImageJ |

| MetaMorph Microscopy Automation & Image Analysis Software | Molecular devices, USA | N/A |

| EnspireManager software | PerkinElmer | Ref# 2300-0000 |

| Leica application suite (LAS) | Leica | N/A |

| Scan 1200 Automatic HD colony counter and Software | Intersciences | Ref. 437 000 |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, François Leulier (francois.leulier@ens-lyon.fr).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Drosophila Stocks and Rearing

A detailed list of fly strains and genotypes used for these studies are provided in the Key Resources Table. Drosophila stocks are routinely kept at 25°C with 12/12 hrs dark/light cycles (lights on at 1pm) on a Rich Yeast Diet (RYD) containing 50g/L inactivated yeast. Poor Yeast Diet (PYD) is obtained by reducing the amount of inactivated yeast to 6g/L. Experiments were performed using standard RYD, modified RYD or PYD poured in 55mm petri dishes (≈7mL of diet) or 1.5mL microtubes (≈100μL of diet). Fresh food was prepared weekly to avoid desiccation, and no yeast paste was added to the medium. Germ Free stocks of different fly strains were established by bleaching and cultivating embryos on fresh RYD supplemented with a cocktail of four antibiotics (RYD-ATB, see below) for at least one generation, and then maintained on RYD-ATB. Axenicity was routinely tested by plating animal lysates on nutrient agar plates. Drosophila y,w flies were used as the reference strain in this work.

Fly Diets Used in This Study

Rich Yeast Diet (RYD): 50g inactivated dried yeast, 80g cornmeal, 7.2g Agar, 5.2g methylparaben sodium salt, 4 mL 99% propionic acid for 1 litre.

RYD+ATB: Same composition as RYD but Ampicillin, Kanamycin and Tetracyclin were added at 50μg/mL final concentration and Erythromycin at 15μg/mL final concentration just before pouring fly food.

RYD+Bromophenol Blue (RYD-BB). Same composition as RYD, BB stock solution was added just before pouring fly food to obtain a final concentration of 0.5% v/v. BB stock solution was obtained by dissolving Bromophenol Blue sodium salt in water at a concentration of 5% w/v. Diet used for taking pictures shown on Figures 1D, 1E, and S1.

Poor Yeast Diet (PYD): 6g inactivated dried yeast, 80g cornmeal, 7.2g Agar, 5.2g methylparaben sodium salt, 4 mL 99% propionic acid for 1 litre.

PYD-ATB: Same composition as PYD but Ampicillin, Kanamycin and Tetracyclin were added at 50μg/ml final concentration and Erythromycin at 15μg/ml final concentration just before pouring fly food.

PYD-BB: Same composition as PYD, BB was added just before pouring fly food at the final concentration of 0.05% v/v. The concentration is lower than in RYD–BB to avoid deleterious effects of high BB concentration on both larval growth and bacterial proliferation. Reduced BB concentration was not adequate for taking pictures but sufficient for visual discrimination of the midgut acid zone and subsequent dissections. Diet used in Figures 1F and 1H.

PYD-Erioglaucine Blue (PYD-EB). Same composition as PYD, Erioglaucine disodium salt powder was directly added to fly food just before pouring at the final concentration of 0.8%w/v. Diet used in Figures 2A, 7C, 7D, and S3D–S3H.

PYD + Protease inhibitors: Protease Inhibitor Cocktail or “PIC” (prepared according to the manufacturer’s guidelines) was added just before pouring fly food at the final concentration of 10% v/v. The control diets (“PYD”) used in the same experiments were obtained by adding water (10% v/v) to PYD just before pouring. Diet used in Figures S3B and S3C.

PYD + N-acetyl-Glucosamine (NAG). Fly food is prepared by mixing 6g of inactive dried yeast, 80g of cornmeal, 7,2g of agar, 5,2g of methylparaben sodium salt, 4 mL of 99% propionic acid in 800 mL water. After cooking and before solidification, 40mL of fly food are mixed with 10mL of a solution of N-acetyl-Glucosamine (prepared from a stock solution at 100g NAG/L sterile water) in a 50mL tube. Fly food is then mixed vigorously by vortexing, and then poured in microtubes.

Fly food was poured in petri dishes (diameter=55mm; fly food volume ≈ 7ml) to grow larvae used for imaging, larval longitudinal length analysis and larval/gut/gut sections bacterial load. Fly food was poured in 1.5ml microtubes (fly food volume=100μl) for diet or niche bacterial load and metabolites profiling. After being poured in microtubes, the flyfood is cut in two after solidification with a sterile Pasteur pipette. This helps homogenous repartition of the inoculum and enhances larval survival at the time of inoculation. Otherwise, the inoculum forms a meniscus on the top of the food, in which young larvae will drown.

Bacteria Culture and Association with Larvae

Lactobacillus plantarumWJL (referred to as LpWJL) is a bacterial strain isolated from adult Drosophila midgut (Ryu et al., 2008). LpWJL was cultivated in Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth medium over night at 37°C without shaking. Precise inoculation and manipulation procedures for each type of experiment are described in more details in “Method Details”. Briefly, LpWJL inoculation of 55mm petri dishes containing fly food are performed as follows: bacterial cultures are centrifuged and supernatant discarded (for more details about bacterial and centrifugation steps, please see (Erkosar et al., 2015). Bacterial pellet is then suspended in 1X PBS to have a final OD=0,5, and 300μL are inoculated onto the diet (“1X” inoculum, ≈7x107 CFUs corresponding to ≈107 CFUs.mL−1 of fly food). Inoculum is homogeneously spread on the food surface, the substrate being previously seeded with 40 freshly laid Drosophila eggs. For other inoculum concentrations, the final OD in PBS is adjusted to keep the inoculation volume constant. For Germ Free controls, an equal volume of sterile PBS is inoculated. For inoculation in microtubes containing fly food, bacteria suspensions at OD=5 in PBS and a volume of 3μl (≈ 7x106 CFUs corresponding to ≈7.107 CFUs.mL−1 of fly food) are used as inocula. For inoculation of heat-killed bacteria, the bacterial pellet is suspended in PBS and the bacterial solution is incubated at 60°C for 4 hr. The heat-treated bacteria solution is plated in parallel on MRS agar to check efficient killing. We also plate larval homogenates on MRS agar to validate larval axenicity at the end of the experiments (for Germ Free controls and larvae inoculated with heat-killed bacteria).

Sex and Developmental Stage of Drosophila Larvae

For the majority of our experiments, we used early third instar Drosophila larvae, unless explicitly written in the figure legends and in the text. The larvae used in these experiments were randomly selected, without distinction between males and females.

Method Details

Standard Monoassocation in Petri Dishes

Axenic adults are put overnight in breeding cages to lay eggs on axenic PYD. Fresh axenic embryos are collected the next morning and seeded by pools of 40 on 55mm petri dishes containing fly food. Bacterial resuspensions (see above) or PBS is then spread homogenously on the substrate and the eggs. Petri dishes are sealed with parafilm and incubated at 25°C until larvae collection.

Monoassociation/Inoculation in Microtubes

This inoculation procedure was followed for niche or diet bacterial load quantification and metabolites profiling (Figure 6). For niche bacterial load and metabolite profiling, axenic parents are put overnight in breeding cages to lay eggs on axenic PYD. PYD is collected the morning after, flies are removed and eggs incubated an additional day at 25°C to let the larvae hatch. Substrate is then flushed with sterile PBS for larvae collection. Pools of 5 larvae (1DAEL, mostly first instar larvae) are gently sampled by pipetting and deposited at the surface of fly food contained in 1.5mL microtubes. Extra water is then carefully pipetted out from the microtube without removing larvae. Finally, microtubes containing larvae are inoculated with bacterial suspension (see above) and incubated at 25°C. For diet bacterial load quantification and diet metabolite profiling, the fly food contained in 1.5ml microtubes was inoculated with bacterial suspension in the absence of larvae and incubated at 25°C.

Delayed Monoassociation

This procedure was followed for Figures 5E and 5F. Axenic adults are put overnight in breeding cages to lay eggs on PYD. Fresh axenic embryos are collected the morning after and seeded by pools of 40 on 55mm petri dishes containing fly food. PBS is spread homogenously on the substrate and eggs, and petri dishes are incubated at 25°C until bacterial inoculation. At Day 1, 3 or 5 after egg laying, bacterial suspension is applied on substrate and larvae, and petri dishes are left at 25°C until larvae collection. Controls for this experiment are larvae inoculated following the standard procedure in 55mm petri dishes.

Bacterial Load Quantification

Larval bacterial loads quantification: larvae are collected from the nutritive substrate and surface-sterilized with a 15 seconds bath in 70% EtOH under manual agitation and rinsed in sterile water. Guts or gut portions are then dissected in PBS if needed. For whole gut samples, portions from the proventriculus (included) and to approximately the 1st half of the hindgut (malpighian tubules removed) are kept. Larvae or dissected guts/guts portions are deposited individually or by pools in 1.5mL microtubes containing 0.75-1mm glass microbeads and 500μL of PBS. For niche (diet+larvae) and diet bacterial load quantification, 0.75-1mm glass microbeads and 500μl PBS are deposited directly onto PYD (+/- larva(e)) contained in microtubes. In all cases, samples are homogenized with the Precellys 24 tissue homogenizer (Bertin Technologies). Lysates dilutions (in PBS) are plated on MRS agar using the Easyspiral automatic plater (Intersciences). MRS agar plates are then incubated for 24 hr at 37°C. The bacterial concentration in initial homogenates is deduced from CFU count on MRS agar plates, using the automatic colony counter Scan1200 (Intersciences) and its accompanying software.

Larval Longitudinal Length Measurement

Drosophila larvae (pools of n ≥ 20 animals) are collected, washed in water, killed with a short microwave pulse (900W for 15 sec), transferred on a microscopy slide, and mounted in water. They are pictured with a Leica stereomicroscope M205FA. Individual larval longitudinal length is then quantified using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012).

Larvae Transfer on Axenic Substrates

This procedure was followed for Figures 2A, 3, 5C, and 5D. Figure 2A: pools of 7DAEL y,w monoassociated larvae reared on PYD are picked out of the food and washed with a 30 seconds bath in sterile water to get rid of contaminated food remnants on their cuticle. Larvae are then transferred in 55mm petri dishes containing axenic PYD-EB. 2 hr post transfer, larvae with entire blue guts coloration (confirming the ingestion of fresh axenic food and the transit of preceding contaminated alimentary bolus) are collected for bacterial load quantification or washed in water before a second transfer on axenic non-colored PYD. 4 hr after the initial transfer, larvae showing no visible trace of blue dye in their guts (confirming the ingestion of fresh non-colored food) are collected for bacterial load quantification or washed in water before a third and last transfer on axenic PYD-EB. 7 hr after the initial transfer; larvae with blue guts are collected for final bacterial load quantification.

Figures 3A–3F: After being reared on PYD, 7DAEL monoassociated larvae (from different genotypes) are picked out from the food and washed with a 30 seconds bath in sterile water to get rid of contaminated food remnants on their cuticle. Larvae are then transferred individually in 1.5ml microtubes containing axenic PYD. The niche (diet+larva), the substrate alone, or larva alone are then processed for bacterial load quantification.

Figure 3G: Axenic PYD was inoculated with 104 CFU/mL of LpWJL, which is approximately the quantity of bacteria found in the food matrix 4 hr post transfer of monoassociated mex> larvae (Figure 3F). We inoculated bacteria alone on food matrixes, or in presence of a single y,w mex> or mex>lab-IR GF larva. We then scored bacterial proliferation after a 20 hr incubation period. Differences (if any) relative to “bacteria alone” controls could be attributable to the presence of larvae. Differences (if any) between larva-containing samples would be attributable to differences in the physiology of larvae of these three different genotypes.

Figures 5C and 5D: y,w monoassociated larvae reared on PYD are picked out of the food at different timings post inoculation, surface-sterilized with a 30 seconds bath in 70% Ethanol under agitation and rinsed in sterile water. Surface-sterilized larvae are then transferred by pools of 40 in 55mm petri dishes containing PYD-ATB and incubated at 25°C before collection and measure at 7DAEL.

Diet Preincubation with Bacteria

This procedure was followed for Figures 5A and 5B. 55mm petri dishes containing PYD are inoculated with OD=0.5 and V=300μl of bacterial suspension or PBS (for controls). Petri dishes are then sealed with parafilm and incubated for a total of 14 days at 25°C. Bacteria killing is performed at different timings during the incubation. At t=0 (straight after inoculation, for controls (PBS inoculated) and “t=0 HK LplWJL”, at t=7 days, and at t=14 days post-inoculation. Bacteria inactivation is obtained by incubating petri dishes at 60°C for 4 hr before putting them back at 25°C.

Diet Preincubation and Larval Growth Gain

We preincubated diet with bacteria and check the effect on larval growth gain. As controls, axenic embryos are seeded on PBS preincubated substrates (diets originally inoculated with PBS, heat-treated at t=0 and incubated for 14 days at 25°C). They are then inoculated with PBS or OD=0.5, V=300μl of bacterial suspension (“Germ Free” and “+ LpWJL” larvae). For the other experimental conditions, axenic embryos are seeded on substrates pre-incubated with bacteria (“t=0, t=7 and t=14 days HK LpWJL”) and inoculated with PBS. Larvae are then incubated on their different substrates for 7 days at 25°C until collection and length measurement. In parallel, we plate larval homogeneates on MRS agar (at the time of collection) to confirm the axenicity of larvae reared on diets pre-incubated with bacteria.

Diet Preincubation and Bacterial Persistence

We preincubated diet with bacteria, larvae, or bacteria and larvae and checked the effect on bacterial persistence (Figures 6F and 6G). Microtubes containing 100 μL of PYD are inoculated, in presence or absence of one 1st instar larvae, with OD=5 and V=3μl of bacterial suspension or PBS. Microtubes are then incubated 7 days at 25°C. After incubation, larvae (when present) are aseptically removed manually, and all microtubes are heat-treated for 4 hr at 60°C for bacteria killing. Microtubes are then allowed to cool down at room temperature before reinoculation with OD=5 and V=3μl of bacterial suspension, and are incubated at 25°C. The evolution of the bacterial titre over time is followed using the procedures detailed below. As contamination controls, pools of n=3 microtubes containing PYD inoculated with LpWJL or with larvae + LpWJL are incubated for 7 days at 25°C before larval removal and heat-treatment. After cool-down, the microtubes are reinoculated with V=3μl of PBS and incubated for 11 days at 25°C before crushing and plating undiluted homogenates on MRS agar plates. Absence of colonies on MRS agar plates guarantees the efficiency of heat treatment for bacterial elimination and the absence of parallel contaminations due to handling procedures.

Bacteria and Larval Homogenate Coinoculation