Abstract

Background:

A randomised phase 2 trial of trimodality with or without induction chemotherapy (IC) in oesophageal cancer (EC) patients showed no advantage in overall survival (OS) or pathologic complete response rate. To identify subsets that might benefit from IC, a secondary analysis was done.

Methods:

The trial had accrued 126 patients (NCT 00525915). Recursive partitioning and proportional hazards regression with interactions were performed.

Results:

The median follow-up of surviving patients was 6.7 years and the median OS duration was 3.8 years (95% confidence interval (CI), 2.6-5.8 years). OS was associated with tumour length (P=0.03), cT (P=0.02), cN (P=0.04), clinical stage (P=0.01), and tumour grade (P<0.001). The effect of IC differed according to tumour grade. Among patients with well or moderately differentiated (WMD) ECs (n=59), the 5-year survival rate was 74% with IC and 50% without IC, P=0.001. IC had no effect on OS of patients with poorly differentiated (PD) ECs (31% and 28%, respectively; interaction, P=0.04; IC, P=0.03). In the multivariate reduced model, WMD with IC was an independent prognosticator for better OS (HR=0.41, 95% CI, 0.25-0.67; P=<0.001). The following four EC phenotypes emerged for OS: (1) very high risk (PD, cN2/N3), (2) high risk (PD, cN0/N1, stage cIII), (3) moderate risk (PD, cN0/N1, stage cI/II or WMD without IC), and (4) low risk (WMD with IC). The 5-year survival rates were 11%, 27%, 48%, and 74%, respectively (P<0.001).

Conclusions:

Our data show that IC significantly prolonged OS of WMD EC patients who undergo trimodality; prospective evaluation is needed.

Keywords: oesophageal cancer, gastroesophageal junction carcinoma, induction chemotherapy, trimodality, randomised trial, prognosis

Although the optimal treatment strategy for resectable oesophageal cancer (EC) has been a subject of debate and research for several decades, survival of EC remains poor (Siegel et al, 2016). Chemoradiation followed by surgery (trimodality treatment) is now the most common treatment strategy for EC in the United States based mainly on the results of a randomised multicentre phase 3 trial in The Netherlands (the CROSS study) (van Hagen et al, 2012), whereas the combination of preoperative chemotherapy and surgery has been the mainstay of EC treatment in some parts of Europe (Cunningham et al, 2006; Stahl et al, 2013). Both of these approaches are now considered standard of care. (Ajani et al, 2015) Cancer-free (R0) resection margin and pathological complete response (pathCR) are the only two factors associated with good survival of EC. The degree of pathologic response is also associated with longer survival and lower rates of recurrence (Chirieac et al, 2005; Wu et al, 2007; Oppedijk et al, 2014; Taketa et al, 2014). To further improve survival, targeted agents have been added but without advantage (Ruhstaller et al, 2011; Idelevich et al, 2012; Stahl et al, 2015). However, our group developed the strategy of induction chemotherapy (IC) followed by chemoradiation and then surgery. We examined the approach in a phase 2 randomised clinical trial but it did not significantly increase the pathCR rate (primary endpoint) or prolong overall survival (OS) durations; The pathCR rate in the control group was 13% (7 of 55) and 26% (14 of 54) in the induction chemotherapy group (P=0.094) (Ajani et al, 2013). Given these results, we did not recommend further development of the strategy but carried out an exploratory analysis to assess if there were subgroups that are likely to benefit. Herein we report on our secondary analysis of the EC patients in the phase 2 randomised trial.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The original phase 2 study was conducted at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2005 to 2011 (NCT 00525915). Patients with local-regional EC (oesophageal or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma) with histologically diagnosed as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma who could tolerate surgery were eligible for the trial. Patients diagnosed with T1N0 disease according to endoscopic ultrasound, T4 tumours with any N stage, and M1 cancer were ineligible. Eligible patients had to have satisfactory organ function, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0-1, age younger than 76 years, and T1N+ or T2–3 EC according to endoscopic ultrasound with any baseline N stage. After all patients provided their written informed consent to participate in the study, the multidisciplinary team evaluated and discussed their cases prior to initiating treatment. The MD Anderson Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. The trial was monitored continuously by the institution’s data and safety monitoring committee.

Therapy

All qualifying patients were randomly put into one of two study arms using an in-house web-based software program that dynamically balanced the two groups according to sex, race, age, tumours histology, and baseline disease stage. All treatments were performed in the outpatient setting. Arm A consisted of chemoradiation followed by surgery, whereas Arm B consisted of IC followed by chemoradiation and then surgery (Supplementary Figure 1).

Patients assigned to Arm A received 50.4 Gy of proton or photon radiation (intensity-modulated) in 28 fractions. At the same time, they received fluorouracil (250 mg m−2 per daily as a 24-h infusion from Monday to Friday for 5 weeks) and oxaliplatin (40 mg/ m−2 intravenously once a week for five doses). After recovery from the chemoradiation for 5–7 weeks, preoperative staging and surgical evaluation of the patients was performed. The surgeries consisted of minimally invasive, three-field, transhiatal, and transthoracic oesophagectomy. Surgery was selected by the operating team. Other routine preoperative investigations were performed.

Patients in Arm B received IC for up to two cycles (8 weeks) before preoperative chemoradiation. IC consisted of a 4-week cycle of 2200 mg/ m−2 fluorouracil infused over 48 h starting on days 1 and 15 and 100 mg/ m−2 oxaliplatin on days 1 and 15. This regimen was a modification of a colon cancer treatment regimen agreed upon by our team and the trial sponsor. Positron emission tomography or endoscopic evaluation of each patient was performed after one cycle of IC to evaluate their treatment responses and monitor EC progression. Patients confirmed to have no progression after the first cycle of IC proceeded to cycle 2, in which they received the same treatment as in Arm A.

Statistical analysis

Dynamic patient randomisation was performed using the method described by Pocock and Simon (Pocock and Simon, 1975). Patient characteristics were tabulated overall and in both treatment arms. OS was defined as the number of years from randomisation to death or last follow-up. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method (Kaplan and Meier, 1958), and median OS durations were reported with 95% confidence intervals. Tumour length, number of SUV avid lymph nodes, baseline T stage, baseline N stage, baseline clinical stage, and tumour grade were clinically relevant tumour measures included in multivariate models used to determine the effect of treatment. Due to the small number, the well-differentiated group was combined with the moderately differentiated group, Stage I was combined with Stage II, and N3 was combined with N2. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models (Cox, 1972) were used to assess the associations between patient characteristics and OS. Clinically relevant tumour measures and the treatment arms were considered in the multivariate (full) model. Backward elimination was implemented until all remaining predictors had P values <0.05 (reduced model). The interaction of treatment arm and categorical patient characteristics were added to the Cox proportional hazards regression models to identify patient subgroups whose tumours may respond well to IC. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using log-rank tests (Mantel, 1966).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were applied to evaluation of the relationships between patient characteristics and pathCR. Exact logistic regression was applied when a subgroup had fewer than five patients with or without a pathCR. Clinically relevant tumour measures and the treatment arms were included in the multivariate model. Backward elimination then was implemented until all remaining predictors had P-values <0.05.

Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was applied to classification of subgroups of patients based on OS or pathCR using the clinically relevant tumour measures and treatment arms (Breiman et al, 1984; Therneau and Atkinson, 1997). The minimum number of patients in any terminal subgroup was set to 15. A two-sided log-rank test was used to assess the differences in OS among the subgroups of patients. A log-rank test was applied in each split and splitting was stopped when the P value for any split was >0.05. Terminal subgroups of patients were compared pairwise using a log-rank test. If the P-value was <0.20, then the two terminal subgroups in the comparison were combined.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS software program (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) except for RPA, which was performed using the R computing language. Figures were created using the Stata software program (version 13.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

We included a total of 126 EC patients with dates of randomisation from April 2005 to May 2011 in this study. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Patients were predominantly white (94%) and male (94%), with most having an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 1 (65%), type 1 adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction (AEG; 64%), an advanced baseline T stage (T3; 84%), an advanced baseline clinical stage (IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC; 60%), adenocarcinoma (97%), and poorly differentiated tumours (53%). We observed an imbalance in ECOG performance status between the two treatment arms (P=0.02), as patients who received IC more often had an ECOG performance status of 0 than did patients who did not undergo IC (44 vs 25%).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

|

n

(%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Without IC | With IC | ||

| Characteristic | (n=126) | (n=63) | (n=63) | P |

| Median age at presentation, years (range) | 60 (27–75) | 60 (29–74) | 60 (27–75) | 0.73 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 118 (94) | 58 (92) | 60 (95) | 0.84 |

| Hispanic | 6 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | |

| Black | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 9 (7) | 4 (6) | 4 (6) | >0.99 |

| Male | 117 (93) | 59 (94) | 59 (94) | |

| Median tumour length, cm (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.87 |

| Median PET SUV (IQR) | 10.1 (7.0–15.4) | 10.1 (7.3–16.3) | 10.1 (6.7–14.3) | 0.62 |

| Number of SUV-Avid LNs | ||||

| 0 | 97 (77) | 44 (70) | 53 (84) | 0.19 |

| 1 | 14 (11) | 9 (14) | 5 (8) | |

| >1 | 15 (12) | 10 (16) | 5 (8) | |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 44 (35) | 16 (25) | 28 (44) | 0.02 |

| 1 | 82 (65) | 47 (75) | 35 (56) | |

| Location of tumour | ||||

| AEG1 | 81 (64) | 41 (65) | 40 (63) | >0.99 |

| AEG2 | 41 (33) | 20 (32) | 21 (33) | |

| Oesophagus | 4 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Baseline T stage | ||||

| T2 | 20 (16) | 9 (14) | 11 (17) | 0.63 |

| T3 | 106 (84) | 54 (86) | 52 (83) | |

| Baseline N stage | ||||

| N0 | 44 (35) | 22 (35) | 22 (35) | 0.39 |

| N1 | 53 (42) | 23 (37) | 30 (48) | |

| N2 | 27 (21) | 17 (27) | 10 (16) | |

| N3 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Baseline clinical stage | ||||

| IB | 7 (6) | 4 (6) | 3 (5) | 0.70 |

| IIA | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | 4 (6) | |

| IIB | 38 (30) | 19 (30) | 19 (30) | |

| IIIA | 49 (39) | 23 (37) | 26 (41) | |

| IIIB | 25 (20) | 15 (24) | 10 (16) | |

| IIIC | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Tumour histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 122 (97) | 61 (97) | 61 (97) | >0.99 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Tumour grade | ||||

| G1 (well differentiated) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0.72 |

| G2 (moderately differentiated) | 58 (46) | 28 (44) | 30 (48) | |

| G3 (poorly differentiated) | 67 (53) | 35 (56) | 32 (51) | |

Abbreviations: IQR= interquartile range; LNs=lymph nodes; PET=positron emission tomography; SUV=standard uptake value.

OS

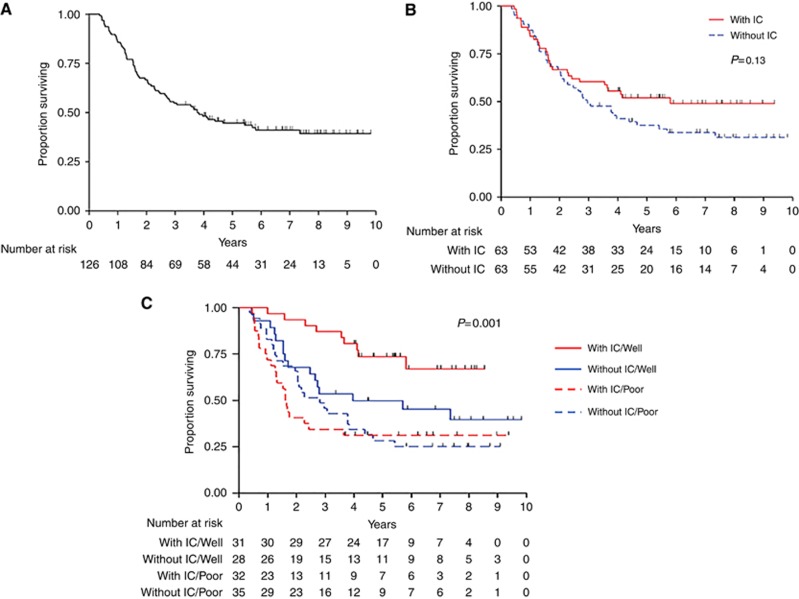

The median follow-up duration in the EC survivors was 6.7 years (range, 3.3–9.8 years). Seventy-three (58%) patients died during the study period, leaving 53 (42%) alive at last follow-up. The median OS duration was 3.8 years (95% confidence interval, 2.6-5.8 years). The 5-year survival rate was 45% (standard error=4%) (Figure 1A). Table 2 lists the OS and 5-year survival rates according to patient characteristics. OS was significantly associated with tumour length (P=0.03), T stage (P=0.02), N stage (P=0.04), clinical stage (P=0.01), and tumour grade (P<0.001). After 2 years of follow-up, OS was longer for the patients who received IC, but this difference was not significant (P=0.13) (Figure 1B). Multivariate OS analysis results are listed in Table 3. Only tumour grade was significantly associated with OS in the full multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, demonstrating that patients with well or moderately differentiated tumours lived longer than did those with poorly differentiated tumours (hazard ratio, 0.44; P=0.001). Use of a reduced multivariate Cox proportional hazards model demonstrated that the effect of baseline T stage on OS became visible and that tumour grade remained significantly associated with OS. Patients with an advanced baseline T stage (P=0.02) or poorly differentiated tumours (P<0.001) were at increased risk for death.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier OS curve. (A) OS for the entire patient population (B) OS by treatment arm. (C) OS by treatment arm and tumour grade. Well, well- to-moderately differentiated tumour; poor, poorly differentiated tumour.

Table 2. OS and 5-year survival rate according to patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Number of deaths (n=73) | 5-year survival rate (SE)a | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation, yearsb | 0.710 | ||

| <60 | 34 | 48% (6%) | |

| ⩾60 | 39 | 42% (6%) | |

| Tumour length, cmb | 0.030 | ||

| <5 | 25 | 54% (7%) | |

| ⩾5 | 48 | 39% (6%) | |

| PET SUVb | 0.640 | ||

| <10 | 32 | 49% (7%) | |

| ⩾10 | 41 | 41% (6%) | |

| Number of SUV-Avid LNs | 0.210 | ||

| 0 | 53 | 49% (5%) | |

| ⩾1 | 20 | 31% (9%) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0.640 | ||

| 0 | 25 | 47% (8%) | |

| 1 | 48 | 44% (6%) | |

| Location of tumour | 0.650 | ||

| Oesophagus/AEG 1 | 50 | 44% (5%) | |

| AEG 2 | 23 | 45% (8%) | |

| Baseline T stage | 0.020 | ||

| T2 | 6 | 75% (10%) | |

| T3 | 67 | 39% (5%) | |

| Baseline N stage | 0.040 | ||

| N0 | 19 | 59% (7%) | |

| N1 | 33 | 43% (7%) | |

| N2/N3 | 21 | 28% (8%) | |

| Baseline clinical stage | 0.010 | ||

| I/II | 21 | 60% (7%) | |

| III | 52 | 35% (6%) | |

| Tumour grade | <0.001 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 48 | 29% (6%) | |

| Well-Moderately differentiated | 25 | 62% (6%) | |

| Treatment Arm | 0.130 | ||

| With IC | 31 | 52% (6%) | |

| Without IC | 42 | 38% (6%) | |

| Treatment arm/tumour gradec | 0.001 | ||

| With IC/ well-moderately differentiated | 9 | 74% (8%) | |

| Without IC/ well-moderately differentiated | 16 | 50% (9%) | |

| With IC/poorly differentiated | 22 | 31% (8%) | |

| Without IC/poorly differentiated | 26 | 28% (8%) | |

| RPA risk groupd | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 9 | 74% (8%) | |

| Moderate | 28 | 48% (7%) | |

| High | 19 | 27% (9%) | |

| Very high | 17 | 11% (8%) |

Abbreviations: LNs=lymph nodes; PET=positron emission tomography; SE=standard error; SUV=standard uptake value.

Entire study population: 45% (4%).

P-values were calculated based on continuous variables for age at presentation at MD Anderson, length of tumour, and positron emission tomography standard uptake value.

OS differed significantly according to treatment arm among patients with well/moderately differentiated tumours (P=0.02) but not among patients with poorly differentiated tumours (P=0.63).

Low risk: well/moderately differentiated tumours with IC; moderate risk: well/moderately differentiated tumours without IC or poorly differentiated tumours, N0/N1 tumours, and stage I/II disease; high risk: poorly differentiated tumours, N0/N1 tumours, and stage III disease; very high risk: poorly differentiated tumours and N2/N3 tumours.

Table 3. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models of OS.

|

Full model |

Reduced model |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Length of tumour | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 0.760 | |||

| Number of SUV-Avid LNs (≥1 vs 0) | 1.16 | 0.66–2.04 | 0.600 | |||

| Baseline T Stage (T3 vs T2) | 2.13 | 0.71–6.35 | 0.180 | 2.70 | 1.17-6.22 | 0.020 |

| Baseline N stage | ||||||

| N1 vs N0 | 1.07 | 0.19–6.08 | 0.940 | |||

| N2/N3 vs N0 | 1.39 | 0.22–8.74 | 0.720 | |||

| Baseline Stage (III vs I/II) | 1.21 | 0.20–7.33 | 0.840 | |||

| Tumour Grade (Well/Moderately Differentiated vs Poorly Differentiated) | 0.44 | 0.26–0.72 | 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.25-0.67 | <0.001 |

| Treatment Arm (With IC vs Without IC) | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | 0.490 | |||

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; LNs=lymph nodes; SUV=standard uptake value.

EC patients possibly benefiting from IC

Table 4 summarises the results of Cox regression analysis of OS when we took into account the interaction between treatment arm and patient characteristics to identify differential treatment effects. We found that the baseline N stage was significantly associated with OS (P=0.02) in the Cox regression model of the interaction between this stage and treatment arm, although the interaction effect was not significant. Importantly, only the interaction between treatment arm and tumour grade was significantly associated with OS (P=0.04). Even with this interaction, the treatment arm (P=0.03) and tumour grade (P<0.001) were both significantly associated with OS, indicating a strong differential effect of treatment on OS depending on tumour grade. Figure 1C shows a Kaplan–Meier OS curve according to treatment arm and tumour grade. The 5-year survival rate did not differ significantly according to treatment arm in the 67 patients with poorly differentiated tumours (31% vs 28% with and without IC, respectively) (Table 2). However, this rate did differ significantly according to treatment arm in the 59 patients with well or moderately differentiated tumours, as more of those who underwent IC than those who did not were alive at 5 years after randomisation (74% and 50%, respectively). The baseline clinical stage in patients with poorly differentiated tumours was higher than that in patients with well or moderately differentiated tumours (P=0.008), but other characteristics were similar in both group.

Table 4. Cox Regression Model of OS with treatment interaction.

| Variable | Treatment P value | Variable P value | Interaction P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of SUV-avid LNs | 0.14 | 0.860 | 0.33 |

| ECOG performance status | 0.16 | 0.900 | 0.68 |

| Tumour location | 0.51 | 0.290 | 0.30 |

| Baseline T stage | 0.13 | 0.150 | 0.75 |

| Baseline N stage | 0.38 | 0.020 | 0.17 |

| Baseline clinical Stage | 0.27 | 0.070 | 0.86 |

| Tumour grade | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: LNs=lymph nodes; SUV=standard uptake value.

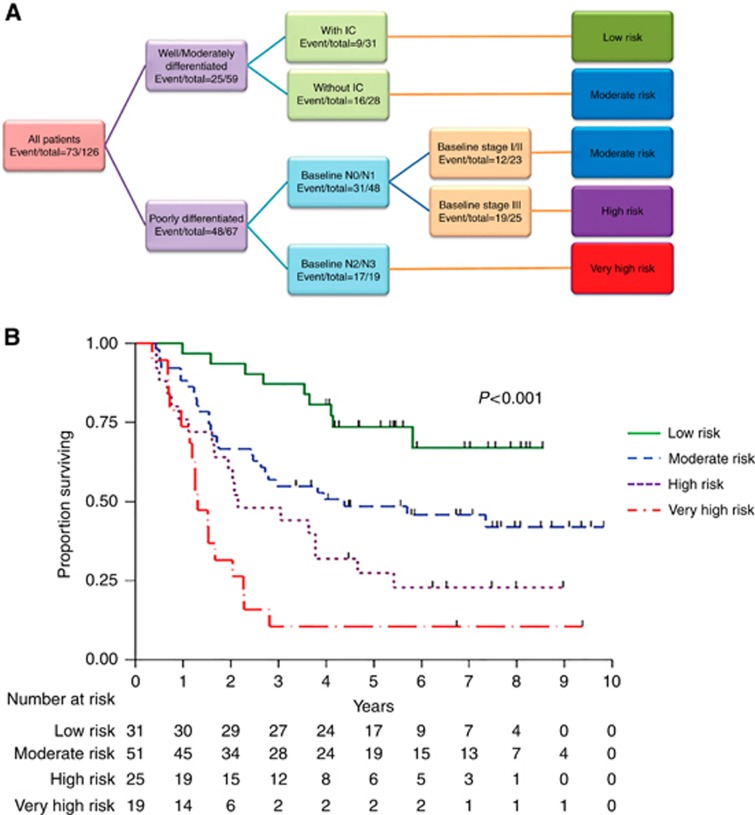

Classification of the four EC phenotypes according to clinical variables

A tree diagram of our RPA-based classification of the study patients into four subgroups based on risk differential is presented in Figure 2A. The original tree is presented with separation according to tumour differentiation, use of IC in patients with well or moderately differentiated tumours, N stage, and baseline clinical stage in patients with poorly differentiated tumours. In the second stage, we combined different branches of patients according to risk group, resulting in four risk groups. The OS comparison among these subgroups is in the bottom of Table 2. Patients in the very high, high, moderate, and low risk subgroups had estimated 5-year survival rates of 11, 27, 48, and 74%, respectively (P<0.001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Four subgroups based on risk differential. (A) Tree diagram of the patient subgroups based on risk differential identified using recursive partitioning analysis (RPA). (B) OS by Risk Groups Identified by RPA.

PathCR

Of the 109 patients known to undergo pathologic response assessment, 21 (19%) had pathCRs. No patient characteristics were significantly associated with pathCR, and we identified no splits using RPA.

Discussion

Although investigators have accomplished much in both basic scientific and clinical research, EC remains an aggressive disease associated with poor OS (Siegel et al, 2016). Preoperative therapy of EC has several theoretical advantages: (1) downsizing the tumour, with increased rates of resection with no tumour within 1 mm of resection margins (R0); (2) early intervention for possible micrometastases; and (3) assessment of response to the initial treatment. On the basis of these possibilities, we previously performed a randomised phase 2 trial that unfortunately demonstrated no improvement in OS or pathCR rate with the addition of IC to chemoradiation followed by surgery (Ajani et al, 2013). Our secondary analysis of the data has produced interesting and hypothesis generating data. Initially, we thought that some patients with poorly differentiated tumours, bulky primary, or advanced baseline N stage would benefit from the addition of chemotherapy prior to chemoradiation. However, we find just the opposite that moderately or well differentiated EC patients are significant beneficiaries of IC. Unfortunately, owing to our small patient population, we cannot conclude that IC is an independent prognostic factor in this subgroup. This strategy can considerably improve outcomes in these patients, though, and it must be evaluated in prospective trials in the near future.

Moreover, we found that the four EC phenotypes classified according to clinical variables were factors for OS. The fact that we picked factors such as tumour differentiation, baseline N stage, and baseline clinical stage supports the usefulness of current EC staging methods.

In conclusion, although further study of this strategy is warranted, using IC before preoperative chemoradiation for EC, may be significantly beneficial to patients who have well or moderately differentiated tumours. However, it should not be administered to those with poorly differentiated tumours. We expect our results to become a springboard for further research and be of some help in establishing this promising strategy, which will improve outcomes and facilitate efficient use of limited medical resources in EC patients.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported by multidisciplinary grants from MD Anderson. It is also supported in part by National Cancer Institute awards CA138671, CA172741, CA150334 (to J.A.A.), and P30CA016672 (the MD Anderson Biostatistics Resource Group). Y.S. was awarded a scholarship from the St. Luke’s Life Science Institute.

Human rights statement and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, Chao J, Das P, Denlinger C, Fanta P, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Glasgow RE, Hayman JA, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jaroszewski D, Jasperson K, Keswani RN, Kleinberg LR, Korn WM, Leong S, Lockhart AC, Mulcahy MF, Orringer MB, Posey JA, Poultsides GA, Sasson AR, Scott WJ, Strong VE, Varghese TK Jr, Washington MK, Willett CG, Wright CD, Zelman D, McMillian N, Sundar H National comprehensive cancer n (2015) Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 1. 2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 13(2): 194–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajani JA, Xiao L, Roth JA, Hofstetter WL, Walsh G, Komaki R, Liao Z, Rice DC, Vaporciyan AA, Maru DM, Lee JH, Bhutani MS, Eid A, Yao JC, Phan AP, Halpin A, Suzuki A, Taketa T, Thall PF, Swisher SG (2013) A phase II randomized trial of induction chemotherapy versus no induction chemotherapy followed by preoperative chemoradiation in patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 24(11): 2844–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Olshen R, Stone C (1984) Classification and Regression Trees. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Chirieac LR, Swisher SG, Correa AM, Ajani JA, Komaki RR, Rashid A, Hamilton SR, Wu TT (2005) Signet-ring cell or mucinous histology after preoperative chemoradiation and survival in patients with esophageal or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 11(6): 2229–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol 34(2): 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ, Smith DB, Langley RE, Verma M, Weeden S, Chua YJ, Participants MT (2006) Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 355(1): 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idelevich E, Kashtan H, Klein Y, Buevich V, Baruch NB, Dinerman M, Tokar M, Kundel Y, Brenner B (2012) Prospective phase II study of neoadjuvant therapy with cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and bevacizumab for locally advanced resectable esophageal cancer. Onkologie 35(7-8): 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Oservations. J Am Stat Assoc 53(282): 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N (1966) Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 50(3): 163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppedijk V, van der Gaast A, van Lanschot JJ, van Hagen P, van Os R, van Rij CM, van der Sangen MJ, Beukema JC, Rutten H, Spruit PH, Reinders JG, Richel DJ, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Hulshof MC (2014) Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J Clin Oncol 32(5): 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Simon R (1975) Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 31(1): 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhstaller T, Pless M, Dietrich D, Kranzbuehler H, von Moos R, Moosmann P, Montemurro M, Schneider PM, Rauch D, Gautschi O, Mingrone W, Widmer L, Inauen R, Brauchli P, Hess V (2011) Cetuximab in combination with chemoradiotherapy before surgery in patients with resectable, locally advanced esophageal carcinoma: a prospective, multicenter phase IB/II Trial (SAKK 75/06). J Clin Oncol 29(6): 626–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66(1): 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl M, Mihaljevic AL, Moehler M, Kanzler S, Hoehler T, Thuss-Patience PC, Moenig SP, Kunzmann V, Schroll S, Lordick F, Meyer H-J, Sandermann A, Schumacher C, Wilke H (2015) Perioperative chemotherapy with ECX +/- panitumumab in locally advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas (GEA): A randomized study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie and the Chirurgische Arbeitsgemeinschaft Onkologie of the German Cancer Society. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33(3_suppl): 104. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl M, Mariette C, Haustermans K, Cervantes A, Arnold D ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2013) Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 24(Suppl 6): vi51–vi56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketa T, Sudo K, Correa AM, Wadhwa R, Shiozaki H, Elimova E, Campagna MC, Blum MA, Skinner HD, Komaki RU, Lee JH, Bhutani MS, Weston BR, Rice DC, Swisher SG, Maru DM, Hofstetter WL, Ajani JA (2014) Post-chemoradiation surgical pathology stage can customize the surveillance strategy in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12(8): 1139–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, Atkinson EJ (1997) An introduction to recursive partitioning using the RPART routines: Report no. 61. Available at: http://www.mayo.edu/research/documents/biostat-61pdf/doc-10026699.

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJ, Busch OR, ten Kate FJ, Creemers GJ, Punt CJ, Plukker JT, Verheul HM, Spillenaar Bilgen EJ, van Dekken H, van der Sangen MJ, Rozema T, Biermann K, Beukema JC, Piet AH, van Rij CM, Reinders JG, Tilanus HW, van der Gaast A Group C (2012) Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 366(22): 2074–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TT, Chirieac LR, Abraham SC, Krasinskas AM, Wang H, Rashid A, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, Ajani JA, Swisher SG (2007) Excellent interobserver agreement on grading the extent of residual carcinoma after preoperative chemoradiation in esophageal and esophagogastric junction carcinoma: a reliable predictor for patient outcome. Am J Surg Pathol 31(1): 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.