Abstract

Objective

Concomitant non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and coeliac disease (CD) have not been adequately studied. This study investigated the frequency of CD among NAFLD patients and the clinicopathological and immunological patterns and outcome of concomitant NAFLD and CD.

Design

This prospective longitudinal study screened patients with NAFLD for CD (tissue transglutaminase antibodies (TTGA); anti-TTGA and antiendomysial antibodies (EMA)). Patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD and patients with either NAFLD or CD were enrolled and followed. Duodenal biopsy, transient elastography, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, transforming growth factor-beta, interleukins (ILs) 1, 6, 10, 15 and 17, folic acid and vitamins B12 and D were performed at baseline and 1 year after gluten-free diet (GFD).

Results

CD was confirmed in 7.2% of patients with NAFLD. Refractory anaemia and nutritional deficiencies were frequent in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD who had advanced intestinal and hepatic lesions, higher levels of TNF-α, IL-15 and IL-17 compared with patients with CD and NAFLD. Patients concomittant CD and NAFLD showed clinical response to GFD, but intestinal histological improvement was suboptimal. Combining EMA-IgA or anti-TTGA with either IL-15 or IL-17 enhances the prognostic performance of both tests in predicting histological response to GFD.

Conclusion

Concomitant NAFLD and CD is not uncommon. Recurrent abdominal symptoms, refractory anaemia, nutritional deficiencies in patients with NAFLD warrant screening for CD. The study has important clinical implications since failure in diagnosing CD in patients with NAFLD patients results in marked intestinal and hepatic damage and suboptimal response to GFD that can be alleviated by early diagnosis and initiation of GFD.

Keywords: celiac disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, cytokines, gluten free diet, small intestinal biopsy

Summary box.

What is already known about this subject?

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may be associated with coeliac disease (CD) in some patients.

The intestinal abnormalities in CD may contribute to NAFLD pathogenesis.

What are the new findings?

This large prospective study identified a set of clinical symptoms and signs that raise the clinical suspicion of CD and warrant testing and identified non-invasive markers that allow better monitoring of response to GFD.

Patients with concomitant NAFDL and CD achieve similar clinical improvement after adherence to gluten free diet. However, histological intestinal improvement is less and delayed in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The study findings may result in better earlier diagnosis and management of CD among patients with NAFLD to improve the outcome and prevent complication of both diseases.

Affordable alternatives of gluten-containing foods will be produced according to the economic status of different communities

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide.1 2 The estimates of the worldwide prevalence of NAFLD ranges from 6.3% to 33%, with a median of 20% in the general population, based on the assessment method.3 However, the estimated prevalence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is lower, ranging from 3% to 5%3 with prevalence rates of 20%–25% in Western countries and 25%–40% in the Middle East.3–7 NAFLD is an important cause of chronic liver disease in Egypt and Arabian Gulf countries such as Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Bahrain and United Arab Emirates (UAE) in adults and paediatric due to the high prevalence of risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome in these countries.8–12 The prevalence of NAFLD ranges between 10% and 15%, between 17% and 52% and between 8% and 11% in Egypt, KSA and UAE, respectively.7–13 NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of conditions ranging from hepatic steatosis, to NASH, to advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.1 Histologically, NAFLD is categorised into non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and NASH. NAFL is defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis with no evidence of hepatocellular injury in the form of ballooning of the hepatocytes. NASH is characterised by the presence of hepatic steatosis and inflammation with hepatocyte injury (ballooning) with or without fibrosis.14 Several metabolic, genetic, inflammatory and environmental factors are involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD.14–17

Coeliac disease (CD), the most frequent food intolerance in the world, is a chronic immune-mediated entropathy resulting from abnormal response to gluten leading to injury to the small intestine, chronic malabsorption, macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies and a wide range of intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations.18–20 Active CD (aCD) may present with abdominal symptoms of different intensity.18 19 However, CD may be silent or latent in some instances.18–21 The prevalence of CD varies between countries and populations. In Europe and the USA, the mean frequency of CD in the general population is approximately 1%22 23 but reaches 1.5%, 1.8%, 2%, 3% in Italy, San Marino, Finland and Sweden, respectively.24–26 Few reports suggested that CD is a common disorder in some North African and Middle Eastern countries26–32; however, the diagnostic rate is still very low in these countries, mostly due to low availability of diagnostic facilities and poor disease awareness. The prevalence and features of CD in Egypt are not clear, and the diagnosis of CD is often missed particularly among adults.

Some studies reported an association of CD with NAFLD.33–39 A study33 showed that patients with NAFLD have 8.6-fold increased risk of CD (95% CI 5.5 to 13.3). Another study demonstrated that 3.4% of studied patients with NAFLD had proven CD.39 However, neither the characteristics nor the significance of such association has been adequately investigated. Therefore, we conducted this prospective, longitudinal, parallel-group, multicentre study to assess the frequency, clinicopathological manifestations, cytokine responses, NAFLD and CD outcome and management in a well-characterised cohort of patients with concomitant CD and NAFLD in addition to patients with either NAFLD alone or CD. We also evaluated the diagnostic and prognostic performance of some serum cytokines for detection of CD in patients with NAFLD and prediction of the response to gluten-free diet (GFD).

Patients and methods

Study design and study population

The current study consists of an initial cross-sectional screening phase followed by a prospective, longitudinal, parallel-group phase. The study was conducted in several Egyptian centres in Cairo, delta and upper Egypt (Ain Shams University Hospitals, Cairo, and gastroenterology centres in Cairo and Minya) and PSAU University Hospital from September 2011 to September 2016. The study protocol and patients’ informed consent were approved by the institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at the participating sites. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with the International Conference on Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice.

Hepatic steatosis grades were assessed by ultrasound (Philips EPIQ7G ultrasound machine; Philips, Reedsville, Pennsylvania, USA) based on visual analysis of the intensity of the echogenicity, provided that the gain setting is optimum. Steatosis is considered grade I (mild) when the echogenicity is slightly increased. In grade 2 (moderate) steatosis, the echogenic liver obscures the echogenic walls of portal vein branches. In grade III (severe steatosis), the echogenic liver obscures the diaphragmatic outline.40 41

Patients with ultrasound findings suggestive of NAFLD/NASH were further tested using ‘NAFLD liver fat score (NAFLD-LFS)’,42 ‘Fatty Liver Index (FLI)’43 and ‘Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI)’44 and were then calculated according to the previously described formulas. Other causes of liver disease and hepatic steatosis were excluded by relevant tests (online supplementary material).

bmjgast-2017-000150supp001.docx (59.5KB, docx)

Patients were enrolled in the study if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) presence of hepatic steatosis; (2) NAFLD-LFS values >−0.640, FLI values >60 and HSI values >36; (3) absence of any evidence of other chronic liver diseases and other causes of hepatic steatosis; (4) no history of significant alcohol consumption and (5) elevated aminotransferase levels found in one of three situations. Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were further evaluated for liver stiffness (LS) and fibrosis assessment by transient elastography (TE). Serial transient elastography (TE; Fibroscan, Echosens, Paris, France) at enrolment and follow-up as previously described and the results were reported in kilopascals (kPa).45

Screening for CD

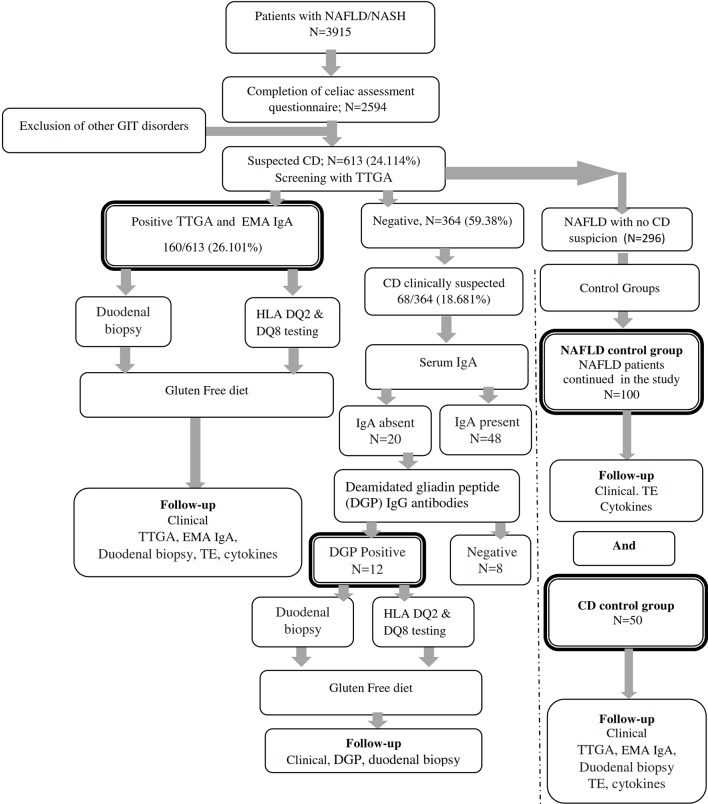

Figure 1 summarises the flow of patients through the study phases. Patients with NAFLD/NASH provided written informed consents before the screening phase of the study. Patients were invited to complete a validated Arabic version questionnaire adapted from the Coeliac UK assessment tool46 in addition to an Arabic locally validated food-frequency questionnaire that captures food intake and dietary intake over 7 days. Patients were then screened by tissue transglutaminase antibodies (TTGA; QUANTA Lite human-TTGA ELISA kit; INOVA Diagnostics, San Diego, California, USA) in which TTGA antibody titres greater than 10 U/mL were considered positive. Antiendomysial antibodies (EMA) (antiendomysial antibody IgA (EMA IgA, ELISA Kit; Biosource, San Diego, California, USA) were used for confirmation of results. Patients with symptoms suggestive of CD but negative TTGA/EMA results were tested for potential IgA deficiency (Abcam human IgA ELISA Kit). Serum IgA concentration <0.07 g/L was considered as IgA deficiency. Patients with IgA deficiency were screened by deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) IgG antibody (DGP IgG ELISA kit). The cut-off levels for positive DGP IgG was 20 U/mL.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the trial. CD, coeliac disease; DGP, deamidated gliadin peptide; EMA IgA, endomysial antibody IgA; GIT, gastrointestinal disorders; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; TE, transient elastography; TTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody.

Patients with positive anti-TTGA, EMA IgA or DGP were informed that they may have CD and were invited to join the study and undergo further investigations. Those who accepted to be enrolled in the study signed another informed consent before entry and before any study-related investigation or upper endoscopy. Enrolled patients completed an Arabic version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale questionnaire (online supplementary material).47 Enrolled patients were subjected to careful history, clinical examination, laboratory investigations, fasting insulin and fasting glucose, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR),48 serum iron, ferritin, folic acid, vitamins D and B12, antinuclear antibodies, thyroid function tests, cytokine assessment and gastrointestinal endoscopy with duodenal biopsy. Lactose intolerance was assessed by lactose tolerance test and lactose hydrogen breath test as previously described.49 DQB1*02 and DQB1*0302 typing (PCR sequence-specific oligonucleotide typing (QIAxcel system and QIAxcel DNA Fast Analysis Kit Product # 929008, QiagenI, Stamford, Connecticut, USA) was performed in a subset of patients.

Cytokines assessment

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL) 1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15 and IL-17 (ELISA Kits, Biosource) and YKL-40 (human YKL-40 ELISA kit, Quidel, San Diego, California, USA) were measured at baseline and end of follow-up according to the manufacturers’ instructions (online supplementary material).

Endoscopy and small intestinal biopsy

At baseline, all patients with serological evidence of CD had upper endoscopy and duodenal biopsy, which were repeated 1 year after GFD in a subset of patients who agreed to the follow-up endoscopy. At least six mucosal biopsies were taken from the second part of duodenum and bulb. Sections were stained with H&E and Giemsa and were examined by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist (author: LN) according to the Modified Marsh classification for CD50 (online supplementary material). Villous atrophy was defined as a Marsh 3 lesion or villous height: crypt depth ratio below 3.0.

Initiation of GFD, monitoring GFD adherence and assessment of response to GFD

Patients diagnosed with CD were informed about the disease and the importance and benefits of following a lifelong GFD. A full nutritional consultation and information sheet including detailed diet regimen and different affordable, easily prepared gluten-free food items were provided to all patients. Adherence to GFD was assessed during clinical visits scheduled every 3 months. During each visit, GFD compliance was assessed by follow-up of initial symptoms or the appearance newly developed ones in addition to completing an Arabic version of Gluten-Free Diet Compliance Questionnaire51 (online supplementary material). After 1 year of GFD, patients repeated EMA IgA or DGP, cytokines, performed follow-up biopsy and TE. Complete clinical improvement was defined as the complete resolution of baseline symptoms after 1 year of GFD. Clinical partial improvement was defined as a resolution of at least 50% of the baseline symptoms after 1 year of GFD. Complete histological improvement is defined as resolution of villous atrophy associated with the absence of crypt hyperplasia and ≤40/100 intraepithelial lymphocytes. Partial histological recovery is defined as improvement of at least one grade on the Marsh classification compared with the initial histology.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were analysed descriptively for all patients using Student’s t tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskall-Wallis test as appropriate for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. Cytokine levels were examined in box plots as continuous variables. A Kruskal Wallis one-way ANOVA test tested for a significant overall shift in cytokine levels in cases and controls, and the Mann-Whitney U test examined identified sample pairs. Comparison of cytokine levels and upper endoscopy findings before and after GFD was assessed by paired t-test. Pearson r correlation test was used to assess the relation between cytokines levels and Marsh class. Using Wilson method, the 95% CIs of the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. Logistic regression was used to predict CD among patients with NAFLD. Results are expressed as mean values±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.22, GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) and Med Calc Statistical software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

Of the 2542 patients with hepatic steatosis who completed the screening questionnaire, 1873 (73.78%) patients fulfilled the criteria of NAFLD and 669 (26.32%) had NASH (data not shown). CD was suspected in 613/2542 patients who were screened by anti-TTGA, which was positive in 160/613 (26.101%) patients. Patients were further tested by EMA IgA. Despite negative TTGA and EMA, CD was still clinically suspected in 68 patients (11.093%). Those patients were tested for serum IgA and DGP IgG antibodies. DGP was positive in 12/68 (17.647 %) tested patients. Thus, serodiagnosis identified 182 NAFLD patients with CD, which represents 7.2% of the patients with NAFLD who completed the initial screening questionnaire. Patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD comprised group A (n=182), patients with NAFLD alone comprised group B (n=100) and 50 patients with proven CD were enrolled in group C.

Patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics and laboratory results

Patients with concomitant CD and NAFLD had significantly lower BMI than those with NAFLD alone (p<0.0001). CD was symptomatic in 123 (67.7%) and 44 (88%) in groups A and C patients, respectively, while silent coeliac was detected in 56 (30.8%) and 6 (12%) patients in groups A and C patients, respectively (table 1). Recurrent bloating, diarrhoea, abdominal pain dyspepsia and nausea were frequently reported by patients with CD with or without NAFLD (table 1). Such abdominal symptoms in NAFLD patients strongly suggested CD (OR: 10.2784; 95% CI 5.9099 to 17.8760; p<0.0001). Dermatitis herpetiformis was detected in 67 (36.8%) and 20 (40%) patients in groups A and C, respectively. Oral ulcers/angular stomatitis occurred in 92 (50.5%) and 21 (42%) of patients with CD with or without NAFLD, respectively (table 1) and strongly predicted CD in patients with NAFLD (OR: 19.4222, 95% CI 7.5483 to 49.9743; Z statistics: 6.152; p<0.0001). Clinical symptoms suggestive of lactose intolerance with positive lactose tolerance test were detected in 15 (8.24%) patients with concomitant coeliac and NAFLD versus 17 (34%) patients with CD (p<0.001). Coeliac crisis with severe diarrhoea and electrolyte disturbances requiring hospitalisation was the presenting symptom in five patients (2.747%) with concomitant NAFLD and CD (who were not aware that they had CD) versus one patient (2%) with proven CD who had a gluten-rich diet. Thyroiditis and diabetes mellitus showed no significant differences in the three groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics and laboratory data of patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD

| Parameter | Group A Patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD n=182 |

Group B NAFLD without CD control group n=100 |

P Value between patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD versus NAFLD control group | Group C Coeliac alone control group n=50 |

P value between patients with CD alone versus patients with concomitant CD and NAFLD |

| Age (years); mean±SD | 42.391±7.374 | 41.968±10.017 | 0.2066 | 38.241±11.286 | 0.0024* |

| Male:Female | 89:93 | 52:48 | 0.8142 | 21:29 | 0.1643 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 24.473±4.207 | 28.718±5.519 | <0.0001** | 22.168±2.137 | 0.0002** |

| Normal (BMI <25) | 159 (87.363) | 5 (5) | <0.0001** | 50 (100) | 0.0056 ** |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–<30) (n (%)) | 19 (10.44) | 58 (58) | <0.0001** | 0 | <0.0001** |

| Obese (30) (n (%)) | 4 (2.19) | 37 (37) | <0.0001** | 0 | <0.0001** |

| Recurrent diarrhoea (n (%)) | 118 (64.835) | 2 (2) | <0.0001** | 30 (60) | 0.6185 |

| Constipation (n (%)) | 8 (4.395) | 36 (36) | <0.0001** | 4 (8) | 0.2942 |

| Abdominal colicky pain (n (%)) | 157 (86.264) | 25 (25) | <0.0001** | 40 (80) | 0.2715 |

| Bloating (n (%)) | 157 (86.264) | 17 (17) | <0.0001** | 47 (94) | 0.2180 |

| Heartburn (n (%)) | 56 (30.769) | 7 (7) | <0.0001** | 14 (28) | 0.862 |

| Nausea/vomiting (n (%)) | 25 (13.736) | 9 (9) | 0.3391 | 19 (38) | 0.0004** |

| Lactose intolerance (n (%)) | 15 (8.242) | 2 (2) | <0.0001** | 17 (34) | <0.0001 ** |

| Coeliac crisis (n (%)) | 5 (2.747) | 0 | <0.0001** | 1 (2) | 1.0000 |

| Clinical jaundice (n (%)) | 24 (13.187) | 45 (45) | 0.0130* | 2 (4) | 0.0784 |

| Reported weight loss (n (%)) | 85 (46.703) | 6 (6) | <0.0001** | 28 (36) | 0.2664 |

| Fatigue (n (%)) | 79 (43.407) | 27 (27) | 0.0342 | 21 (42) | 0.8736 |

| Bone or joint pain (n (%)) | 53 (29.212) | 18 (18) | 0.0619 | 13 (26) | 0.7261 |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis (n (%)) | 67 (36.813) | 1 (1) | <0.0001** | 20 (40) | 0.7422 |

| Numbness in hands and/or feet (n (%)) | 28 (15.385 | 8 (8) | 0.0932 | 7 (14) | 1.000 |

| Oral ulcers/angular stomatitis (n (%)) | 92 (50.549) | 3 (3) | <0.0001** | 21 (42) | 0.3385 |

| Thinning of hair (n (%)) | 31 (17.033) | 15 (15) | 0.7376 | 17 (34) | 0.0011** |

| Irritability/anxiety (n (%)) | 19 (10.439) | 6 (6) | 0.3773 | 9 (18) | 0.1487 |

| Depression (n (%)) | 13 (7.143) | 3 (3) | 0.1854 | 11 (22) | 0.0065* |

| Family history of proven CD (n (%)) | 6 (3.297) | 0 | <0.0001** | 10 (20) | 0.0003 ** |

| Diabetes (n (%)) | 41 (22.527) | 26 (26) | 0.5594 | 13 (26) | 0.7057 |

| Thyroid disease (n (%)) | 19 (10.439) | 14(14) | 0.4392 | 9 (18) | 0.1487 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (normal: 0.3–1.0 mg/dL) | 2.04±1.85 | 1.97±1.06 | 0.7217 | 1.39±0.72 | 0.0150 * |

| ALT (U/L) (normal: 10–40 U/L) | 98.3±31.27 | 67.2±26.14 | <0.0001 | 46.31±9.47 | <0.0001** |

| AST (U/L) (normal: 10–40 U/L) | 69.36±29.46 | 59.92±21.74 | 0.0038 | 42.18±10.15 | <0.0001** |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) (normal: 3.5–5.5 g/dL) |

3.5±0.81 | 3.6±0.21 | 0.3870 | 3.635±0.88 | 0.2035 |

| HOMA-IR score | 4.931±2.43 | 4.615±3.241 | 0.3164 | 2.305±2.363 | <0.0001** |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (normal: <150 mg/dL) |

148.753±32.184 | 141.83±29.38 | 0.0619 | 124.51±20.16 | <0.0001** |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) (normal: <200 mg/dL) |

198.23±27.68 | 181.065±21.78 | <0.0001 | 135.64±26.18 | <0.0001** |

| Haemoglobin (range: men: 13.5–17.5 g/dL; women: 12.0–15.5 g/dL) |

9.48±2.13 | 13.52±2.17 | <0.0001 | 9.893±2.607 | 0.2494 |

| RBCs (1×106 cells/µL) (range: men: 4.7–6.1 million cells/µL; women: 4.2–5.4 million cells/µL) |

3.102±0.52 | 4.21±0.86 | <0.0001 | 3.004±0.859 | 0.2805 |

| Total leucocytic count (range: 4500–10 000 cells/µL) | 6674±2730 | 7621±3.86 | 0.8469 | 6293±3104 | 0.1430 |

| Platelets (range: 150 000–450 000/µL |

179 271±71 201 | 193 194±48 937 | 0.0202* | 195 107±73 286 | 0.7112 |

| Serum iron (µg/dL) (60–178 µg/dL) |

63.816±31.948 | 173.716±39.851 | <0.0001** | 59.486±19.643 | 0.3558 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) (range: 10–250 ng/mL) | 106.319±38.821 | 198.317±49.182 | <0.0001** | 105.425±41.106 | 0.8826 |

| HLA DQ2 | 38/40 (75%) | 2/12 (16.667) | <0.0001** | 13/16 (93.75) | 0.0269* |

| HLA DQ8† | 1/40 | 4/16 | |||

| CD status | 0 | – | |||

| Symptomatic CD | 123 (67.68) | 44 (88) | 0.0042* | ||

| Silent CD | 59 (32.42) | 6 (12) | 0.0004* | ||

| Latent CD | 0 | 0 |

p, P value (Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables).

*Significant.

**Highly significant.

†HLA analysis was performed in 40 patients in group A, 12 patients in group B and 16 patients in group C.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CD, coeliac disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; RBCs, red blood cells.

Patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD had significantly higher serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and asparta aminotransferase (AST), cholesterol and triglyceride levels and HOMA-IR compared with groups B and C. Patients with CD with or without NAFLD showed low haemoglobin, serum iron, ferritin, folic acid, vitamin D and vitamin B12 compared with patients with NAFLD alone (p<0.0001 for all) (tables 1 and 2). The following findings were significantly associated with CD in patients with NAFLD: haemoglobin levels <10 gm/dL (OR: 9.8358; 95% CI 5.6457 to 17.1355; p<0.0001), iron levels <60 µg/dL (OR: 13.0473; 95% CI 7.4001 to 23.0038; p<0.0001), folic acid levels below 2 ng/mL (OR: 11.0968; 95% CI 6.2783 to 19.6134; p<0.0001) and vitamin B12 levels below 200 pg/mL (OR: 6.4286; 95% CI 3.8458 to 10.7460; p<0.0001). DQ2 and DQ8 were positive in 51 (91.07%), 42 (42%) and 5 (8.93%) patients in groups A, B and C, respectively.

Table 2.

Serum iron, folic acid, vitamins, EMA IgA, TTGA and cytokine levels at baseline and after GFD in patients with concomitant NAFLD and coeliac disease versus patients with coeliac disease control group

| Parameter | Concomitant NAFLD and coeliac disease n=182 |

P value between baseline and post-GFD levels | Coeliac disease control group n=50 |

P value between baseline and post-GFD levels | p value between patients with concomitant coeliac disease and NAFLD versus patients with coeliac disease alone | ||

| Baseline | After GFD | Baseline | After GFD | ||||

| Serum iron (µg/dL); (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

63.816±31.948 (59.922 to 67.71) |

97.419±48.571 (91.499 to 103.339) |

<0.0001** | 59.486±19.64 (53.90352 to 65.068) |

101.317±37.468 (90.669 to 111.965) |

<0.0001** | Baseline: 0.3558 After GFD: 0.5914 |

| Folic acid (ng/mL); (mean±SD) (95% CI) | 2.817±2.014 (2.572 to 3.062) |

5.082±3.749 (4.6255 to 5.539) |

<0.0001** | 3.219±1.651 (2.7498 to 3.688) |

4.948±3.758 (3.879 to 6.016) |

0.0037** | Baseline: 0.0491 After GFD: 0.8171 |

| 1,25-Dihydroxy-cholecalciferol (ng/mL); (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

21.725±7.196 (20.848 to 22.602) |

32.873±9.274 (31.743 to 34.003) |

<0.0001** | 20.868±6.265 (19.088 to 22.648) |

34.057±8.763 (31.567 to 36.547) |

<0.0001** | Baseline: 0.4321 After GFD: 0.4049 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL); (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

268.283±164.831 (248.192 to 288.374) |

406.618±194.586 (382.901 to 430.335) |

<0.0001** | 235.664±198.569 (179.23134 to 292.097) | 397.756±269.027 (321.299 to 474.213) |

0.0009** | Baseline: 0.2165 After GFD: 0.7829 |

| TTGA (U/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

410.629±140.931 (393.452 to 427.807) |

113.726±49.594 (107.68118 to 119.77082) |

<0.0001** | 438.152±200.281 (381.233 to 495.071) |

99.395±33.170 (89.968 to 108.82181) |

<0.0001** | Baseline: 0.241 After GFD: 0.0509 |

| IL-1 (pg/mL); (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

728.0154±212.625 (699.399 to 748.968) |

195.286±103.715 (182.66896 to 207.90304) |

<0.0001** | 775.0962±161.67787 (767.718 to 861.0518) |

215.004±95.004 (188.00417 to 242.00383) |

<0.0001** | Baseline: 0.139 After GFD: 0.2131 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

552.4791±191.130 (479.818 to 543.437) |

115.027±124.570 (99.84365 to 130.21035) |

<0.0001** | 612.8123±193.63434 (557.7820503 to 667.8425497) |

98.618±87.736 (73.68371 to 123.55229) |

<0.0001** | Baseline:0. 042 After GFD: 0.3744 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

229.163±31.701 (225.29909 to 233.02691) |

199.429±31.578 (195.58008 to 203.27792) |

<0.0001** | 239.429±41.772 (234.241 to 258.251) |

187.6482±34.862 (177.740533 to 197.555867) |

0.0123 | Baseline: 0.011 After GFD: 0.0180 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

109.0846±56.767 (102.165 to 116.004) | 107.104±84.213 (96.83961 to 117.36839) |

0.7528 | 122.4574±62.516 (104.690556 to 140.2242) | 116.625±83.280 (92.95709 to 140.29291) |

0.6939 | Baseline: 0.134 After GFD: 0.4640 |

| IL-15 (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

388.1054±202.695 (284.188 to 303.458) |

87.392±39.481 (82.579 to 92.204) |

<0.0001** | 419.7824±240.104 (363.399 to 412.811) | 98.27±55.241 (82.57069 to 113.9693) |

<0.0001** | Baseline:0. 327 After GFD: 0.0973 |

| IL-17 (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

420.6127±189.19547 (397.5524076 to 443.6729924) | 171.725±94.104 (160.25503 to 183.19497) | <0.0001** | 440.3236±274.07684 (362.4312535 to 518.2147465) |

154.293±98.328 (126.34850 to 182.23750) |

<0.0001** | Baseline: 0.534 After GFD: 0.3673 |

| TGF-β (pg/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

519.5356±137.25651 (502.8053434 to 536.2646566) |

482.265±117.975 (67.88549 to 496.64451) |

0.0009 | 114.4371±65.74532 (95.752585 to 133.121615) |

112.208±82.094 (94.87715 to 135.53885) |

0.8812 | Baseline:<0.0001** After GFD:<0.0001** |

| YKL-40 (ng/mL) (mean±SD) (95% CI) |

256.0656±58.73954 (248.9060683 to 263.2251317) |

271.319±35.815 (266.95365 to 275.68435) |

0.0004 ** | 58.73954±21.309 (52.683 to 64.795) |

45.482±69.284 (25.79171 to 65.17229) |

0.1989 | Baseline:<0.0001** After GFD:<0.0001** |

Values are means±SD.

*Significant.

**Highly significant.

EMA IgA, endomysial antibodies IgA; GFD, gluten-free diet; IL, interleukin; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta; TTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody; YKL-40: chitinase-3-like-1 human cartilage glycoprotein-39.

Clinical response to GFD in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD versus patients with CD alone

Complete clinical improvement after GFD was achieved in 159 (87.363%) and 47 (94%) patients in groups A and C, respectively (p=0.3092). Partial improvement was detected in 18 (9.89%) and 3 (1.648%) patients in groups A and C, respectively (p=0.5813). Five patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD showed refractory CD (data not shown). Adherence to GFD resulted in clinical improvemnt as well as improvement in the nutritional parameters such as serum iron, folic acid and vitamins B12 and D (table 2).

Baseline and follow-up intestinal biopsy

At baseline, Marsh stage 3 (a, b and c) intestinal changes were detected in 181 (99.45%) and 47 (94%) patients in groups A and C, respectively (p=0.0323) (table 3). Thus, according to clinical manifestations, serology and baseline intestinal biopsy, patients with CD were classified into: (1) symptomatic CD with manifestations related to coeliac with positive serology and histological manifestations in intestinal biopsy; (2) silent CD with no or minimal symptoms, ‘damaged’ mucosa and positive serology; and (3) latent CD with positive serology but with normal intestinal mucosa and no symptoms (table 1). After 1 year of GFD, intestinal biopsy was performed in 101 patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD and 42 patients with sole CD. Complete histological improvement was achieved in 13 (12.87%) and 42 (84%) patients in groups A and C, respectively (p<0.0001). Partial histological improvement was detected in 79 (78.217%) and 8 (16%) patients in groups A and C, respectively (p<0.001). No improvement was detected in nine (8.91%) patients with concomitant NAFL and CD (table 3).

Table 3.

Modified Marsh Classification of histological findings (Oberhuber) in patients with concomitant CD and patients with CD alone at baseline and after GFD

| Marsh modified (Oberhuber) | Group | ||||||

| Class | Concomitant NAFLD and CD n=101 |

P value before versus after GFD |

CD n=30 |

P value before versus after GFD |

P value between concomitant NAFLD and CD and CD alone |

||

| Before GFD N (%) |

After GFD N (%) |

Before GFD N (%) |

After GFD N (%) |

||||

| Type 0 | 0 | 13 (12.871) | <0.0001** | 0 | 42 (84) | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 1.000 After GFD: 0.0306 |

| Type 1 | 0 | 79 (78.217) | <0.0001** | 0 | 8 (16) | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 1.000 After GFD:<0.0001 |

| Type 2 | 1 (0.99) | 2 (1.98) | 0.4448 | 3 10) | 0 | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 0.3830 After GFD:<0.0001 |

| Type 3a | 63 (62.376) | 7 (6.93) | <0.0001** | 12 (40) | 0 | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 0.2654 After GFD:<0.0001 |

| Type 3b | 23 (22.772) | 0. | <0.0001** | 9 (30) | 0 | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 0.2094 After GFD:<0.0001 |

| Type 3c | 14 (13.861) | 0 | <0.0001** | 6 (20) | 0 | <0.0001** | Before GFD: 0.3991 After GFD: 1.0000 |

| Complete histological improvement (n (%)) | 23 (22.772) | 42 (84) | p<0.0001 | ||||

| Partial histological improvement (n (%)) | 69 (68.316) | 8 (16) | p<0.0001 | ||||

| No improvement (n (%)) | 9 (8.91) | 0 | p<0.0001 | ||||

Histological classification is according to Modified Marsh Classification of histological findings in CDceliac disease (Oberhuber).42 The classification depends on assessment of four indicators: IEL/100 (intraepithelial lymphocytes) enterocytes jejunum, IEL/100 enterocytes duodenum, crypts hyperplasis and villi.

Classification:

type 0: normal mucosa; type 1: seen in patients on GFD (suggesting minimal amounts of gluten or gliadin are being ingested); patients with dermatitis herpetiformis; family members of patients with CD, not specific, may be seen in infections; type 2: seen occasionally in dermatitis herpetiformis; type 3: spectrum of changes seen in symptomatic CD.

The same classification system was used to assess the endoscopic appearance before GFD and 1 year after beginning the GFD; the endoscopist who performed the follow-up gastroscopy was unaware of the baseline endoscopic appearance. Complete histological improvement is defined as resolution of villous atrophy associated with the absence of crypt hyperplasia and ≤40/100 intraepithelial lymphocytes. Partial histological recovery is defined as improvement of at least one grade on the Marsh classification compared with the initial histology.

**Significant at p<0.05.

CD, coeliac disease; GFD, gluten-free diet; NAFLD, non alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Baseline and follow-up serum TTGA, EMA and cytokines

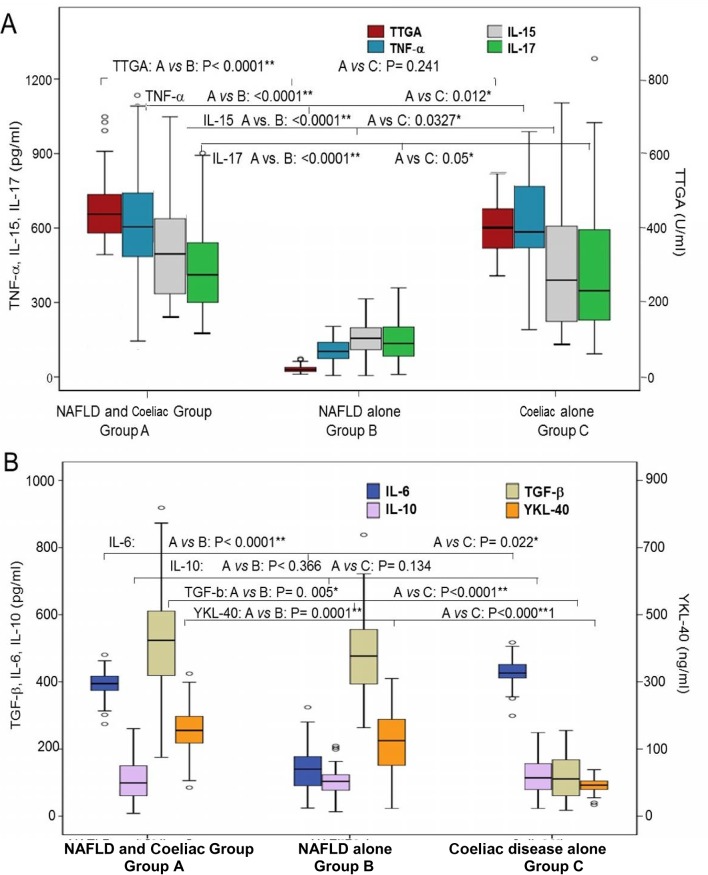

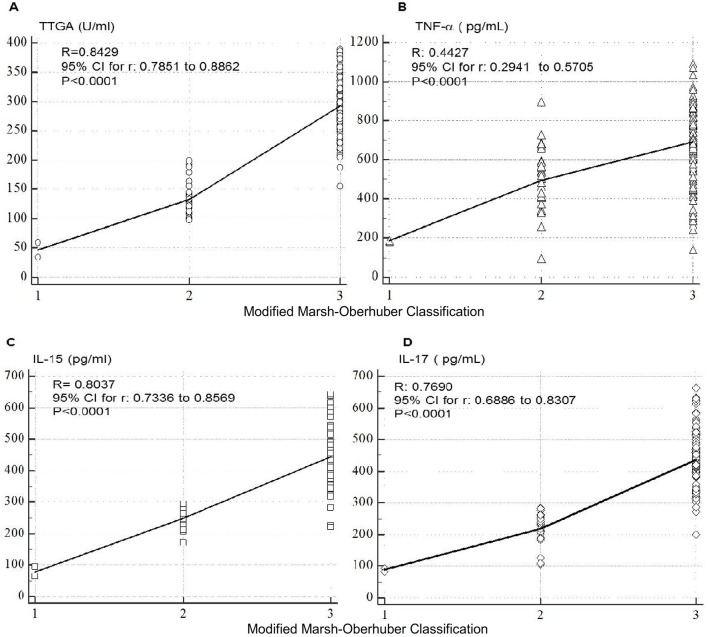

At baseline, anti-TTGA, IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-15, IL-17 cytokines were significantly higher in patients in groups A and C compared with those in group B (table 2, figure 2). TTGA, EMA, TNF-α, IL-15 and IL-17 titres correlated swith the severity of intestinal lesions in groups A and C patients (figure 3). TGF-β and YKL-40 were significantly higher in patients with NAFLD with or without CD compared with those with NAFLD alone (p<0.0001) (figure 2B) with significant differences between patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD and NAFLD alone (TGF-β: p=0.005, YKL-40: p=0.001). As shown in table 2, clinical improvement was associated with significant reduction in TTGA, IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6 as well as IL-15 and IL-17.

Figure 2.

Baseline cytokines in the three groups. (A) Baseline TTGA, TNF-α, IL-15 and IL-17 and (B) IL-6, IL-10 and TGF-β and YKL-40 in patients of the three groups. Group A: concomitant NAFLD and coeliac disease (n=182); group B: NAFLD (n=100); group C: coeliac disease (n=50). In the box plot, the black centre line represents the median for each dataset. The first and third quartiles (IQR) are located at the edges of the box. The points represent outliers. *Significant. **Highly significant. IL, interleukin; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody; YKL-40: chitinase-3-like-1 human cartilage glycoprotein-39.

Figure 3.

Correlation between individual cytokines and Modified Marsh classification for coeliac disease that assesses the intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 enterocytes (IEL/100 enterocytes), crypt hyperplasis and villi.42 IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody.

Diagnostic performance of TTGA, EMA IgA and serum cytokines in predicting CD in patients with NAFLD

Considering histological changes in intestinal biopsy as the gold standard for diagnosis of CD, we assessed the diagnostic performance of TTGA, EMA IgA and the tested cytokines. EMA IgA, IL-17, TTGA, TNF-α and IL-15 showed the high sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV in predicting the status of CD (Table 4). Combining the results of EMA IgA and TTGA with either TNF-α, IL-15 or IL-17 further improved the diagnostic performance of such cytokines (table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic performance of different antibody tests and cytokines in predicting coeliac disease in patients with NAFLD

| Cytokine | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Positive prepvdictive value | Negative predictive value |

| TTGA (95% CI) | 96.02% (92.80% to 98.07%) | 90.62% (88.83% to 95.43%) | 0.94 (0.90 to0.96) | 92.34% (88.76% to 94.84%) | 96.17% (93.18% to 97.88%) |

| EMA IgA (95% CI) |

97% (91% to99%) | 88% (65% to92%) | 0.91 (0.85 to0.97) | 89% (78% to94%) | 91% (79% to97%) |

| TNF-α (95% CI) | 95.60% (92.26% to 97.78%) | 91.91% (88.01% to 94.86%) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.96) | 91.57% (87.91% to 94.20%) | 95.79%–92.72% to 97.59 |

| IL-1 (95% CI) | 88.51% (84.00% to 92.11%) | 89.29% (85.06% to 92.65%) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.91) | 88.51% (84.56% to 91.55%) | 89.29% (85.58% to 92.12%) |

| IL-6 (95% CI) | 95.26% (91.46% to 97.70%) | 83.11% (78.40% to 87.16%) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | 79.76% (75.39% to 83.53%) | 96.17% (93.19% to 97.88%) |

| IL-10 (95% CI) | 69.35% (63.37% to 74.89%) | 52.38% (44.55% to 60.13%) | 0.61 (0.56 to 0.66) | 69.35% (65.44% to 73.00%) | 52.38% (46.57% to 58.12%) |

| IL-15 (95% CI) | 95.85% (92.50% to 97.99%) | 89.32% (85.11% to 92.68%) | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.95) | 88.51% (84.58% to 91.53%) | 96.17% (93.18% to 97.88%) |

| IL-17 (95% CI) | 94.72%–91.29% to 97.08% | 96.11% (92.96% to 98.12%) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.97) | 96.17% (93.18% to 97.88%) | 94.64%–91.37% to 96.71% |

| TTGA plus EMA IgA (95% CI) | 98% (90% to99%) | 95% (75% to97%) | 92% (82% to95%) | 93% (81% to98%) | |

| TTGA+TNF-α (95% CI) | 96.24% (93.20% to 98.18%) | 98.05% (95.50% to 99.36%) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98) | 98.08% (95.55% to 99.19%) | 96.17% (93.18% to 97.88%) |

| TTGA+IL-15 (95% CI) | 97.65% (94.95% to 99.13%) | 95.52% (92.31% to 97.67%) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98) | 95.40% (92.27% to 97.30%) | 97.71% (95.08% to 98.95%) |

| TTGA+IL-17 (95% CI) | 98.10% (95.62% to 99.38%) | 98.84% (96.65% to 99.76%) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 98.85% (96.54% to 99.62%) | 98.08% (95.55% to 99.19%) |

AUC, area under the curve; EMA IgA, endomysial antibody IgA; IL, interleukin; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody.

Impact of CD in liver histology and hepatic fibrosis progression

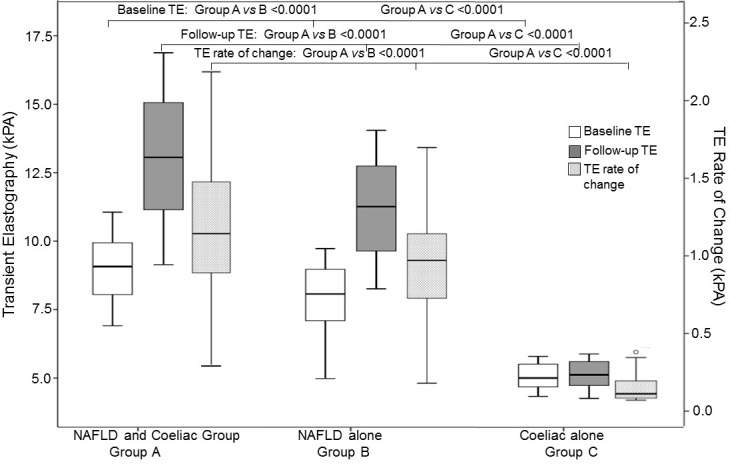

Baseline and follow-up LS values and TGF-β and YKL-40 levels showed significant differences between groups A, B and C patients. At the end of follow-up, more patients with concomitant NAFDL and CD progressed to NASH than patients with NAFLD alone (figure 2b, figure 4).

Figure 4.

Baseline and follow-up transient elastography (TE) in patients with concomitant NAFLD and coeliac disease (n=182; group A), patients with NAFLD (n=100; group B) and patients with coeliac disease alone (n=50; group C). NAFLD, NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Discussion

Given that the features and outcome of concomitant NAFLD and CD are not adequately investigated, we conducted the current prospective longitudinal study to investigate the frequency of CD among adult patients with NAFLD and investigate the clinical, histological and immunological features as well as the management of these patients.

In the current study, CD was diagnosed by TTGA/EMA IgA or DPG and intestinal biopsy in 7.2% of our patients with NAFLD, which is within the range of 2%–14% that was reported in previous studies.33–36 38 Although two-thirds of patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD had gastrointestinal symptoms of varying intensity, CD was neither diagnosed or suspected prior enrolment in the study due to either low awareness of celiac disease or the unavailability and high costs of CD diagnostics. In the current study, undiagnosed recurrent bloating, repeated diarrhoea with or without angular stomatitis or dermatitis herpetiformis or suboptimal BMI (<24) or refractory anaemia, nutritional (vitamin B12, vitamin D and folic acid) in patients with NAFLD deficiencies were associated with high likelihood of CD and represented important warning signs raising the clinical suspicion of CD in patients with NAFLD and warranting screening.

The advanced intestinal inflammation and villous atrophy and higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines observed in our patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD suggest advanced intestinal injury in such patients compared with those with sole CD. Also, patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD had higher levels of hepatic steatosis, LS, hepatic fibrosis progression rates and profibrotic mediators compared with those with either NAFLD or CD alone. Such differences in severity of intestinal and hepatic damage may have several potential explanations. The previous diagnosis of coeliac enteropathy in several patients with sole CD and the initiation of GFD at some time point (despite lack of GFD strict compliance in the majority of patients) may have reduced intestinal lesions to some extent. In contrast, none of our patients with NAFLD was previously diagnosed with coeliac so patients pursued consuming typical Egyptian gluten-rich diet resulting in ongoing enteropathy, significant intestinal damage with release of proinflamatory cytokines, increased intestinal permeability and gut bacteria dislocation.52 53 The intestinal microbiome may increase influx of fatty acids intestinally derived toll-like receptor 4 and toll-like receptor 9 agonists into the efflux of the liver through the portal circulation which, in turn, activate hepatic TNF-α mediating the pathogenesis of NAFLD and its progression to NASH.53 Another explanation may be that patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD initially developed hepatic steatosis (due various risk factors), which represented the primary hit and CD gut-derived endotoxaemia represented the second hit that accelerated progression of NAFLD.37 54

Initiation and compliance to a GFD has been a real challenge in the current study. Gluten-containing foods are the cornerstone of the typical Egyptian diet characterised by inclusion of wheat and bread in almost all Egyptian meals. GFDs are rarely available in the Egyptian market, and if found they are extremely expensive and beyond the reach of the majority of patients. In the current study, it was mandatory to provide patients with detailed nutritional consultation and recipes of affordable GFDs from corn and rice flour. In the current study, CD patients with or without NAFLD showed significant clinical improvement after adherance to GFD. However, complete histological recovery was less or delayed in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD. This might be due to consumption of minimal amounts of gluten or due to potential cross-contamination while preparing food or due to the more baseline advanced intestinal damage in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD.

To date, histology of intestinal biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of CD and confirming complete response to GFD in many regions because other diagnostic procedures maybe unavailable.55 However, upper endoscopy is an invasive, expensive procedure, and repeating endoscopy for follow-up of the response of patients to GFD is inconvenient to many patients. Thus, we investigated the clinical utility of other potential non-invasive methods for screening, diagnosis and follow-up of CD. The current study showed that anti-TTGA was a good screening test with reasonable sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV; however, EMA IgA may be beneficial in confirming CD in anti-TTGA positive cases particularly in patients with concomitant NAFLD/NAASH. Some studies showed false-positive TTGA results in patients with connective tissue disorders, inflammatory bowel diseases and in chronic liver disease of different aetiologies. False-positive results of human TTGA in chronic liver disease may arise from evoking an immune response that is to some degree related to the amount of liver fibrosis probably because of the hepatic expression of TTGA.56–59 A study showed that that TTGA may play a role in the course of hepatic repair following a prolonged toxic injury, stress-induced damage and may be expressed in the progression of liver damage. However, the current study showed that EMA followed by TTGA with IL-17 or IL-15 have better sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV and more accuracy in predicting histological response to GFD than TTGA alone. Comparing the costs and benefits of endoscopic intestinal biopsy with EMA IgA or TTGA with cytokine use favours serology.

In accordance with previous studies,19–21 HLA DQ2 and DQ8 were detected in our CD patients with or without NAFLD. Although the current study shows that HLA DQ2 seems less prevalent in patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD, it is hard to make reliable conclusions since HLA phenotyping was performed only in a subset of patients. Taken together, HLA testing may not be incorporated as a routine diagnostic procedure for CD, particularly in resource-limited countries since it does not reflect the activity of the disease and adds to the costs of diagnosis.

The current study has several strengths such as the prospective longitudinal design, the well-characterised cohort, the comprehensive assessment of clinical, histopathological, immunological characteristics of patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD and the long follow-up. The study provided a set of clinical warning signs and non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic methods for detection of CD and in monitoring the response to GFD. The study also demonstrate the negative impact of CD on NAFLD. However, the study also has some limitations including screening patients for CD according to self-reported symptoms so latent CD may have been missed. Post-GFD intestinal biopsies were performed in a subset of patients who approved endoscopy. However, the missing follow-up intestinal biopsy results in some patients were statistically handled. Liver biopsies were not performed, and diagnosis of NAFLD depended on ultrasound and the FLI and HSI. Given the high prevalence of NAFLD in general population, it may be argued that the presence of NAFLD in patients with CD can be accidental, which cannot be entirely ruled out in the current study. Some studies28–30 55 showed that the frequency of CD in the general population is 0.53% and 6.4% among at-risk groups. However, large studies are needed to accurately assess the true prevalence of CD in patients with NAFLD and NASH in comparison with its prevalence in the general population.

Taken together, our study provided important new data that have various clinical implications. Our study showed that CD is not uncommon among patients with NAFLD but is often missed or ignored. The study identified a set of clinical warning signs and non-invasive biomarkers that increase the identification of CD in patients with NAFLD and monitoring of both diseases. Concomitant NAFLD and CD may have advanced intestinal damage and more advanced forms of NAFLD suggesting that both disorders have negative impact on each other. Thus, current study highlighted the importance of early detection and management of CD in patients with NAFLD to improve the outcome and reduce complications of both disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University. The authors would like to thank Dr Yasmin Massoud for her contribution in enrollment, clinical examination and follow-up of the patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed in clinical work, patient enrolment, data collection, data entry and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (grant no: PSAU291625), Ain Shams University (grant no: R-2094-2011), Science & Technology Development Fund (STDF) (grant no: STDF/384/2011-2015).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ain Shams University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional anonymous unpublished data from the study are available. The data may be accessed by the investigators.

References

- 1. Bedossa P. Pathology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2017;37(Suppl 1):85–9. doi:10.1111/liv.13301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: selected practical issues in their evaluation and management. Hepatology 2009;49:306–17. doi:10.1002/hep.22603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellentani S. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2017;37(Suppl 1):81–4. doi:10.1111/liv.13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. . Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84. doi:10.1002/hep.28431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bedogni G, Miglioli L, Masutti F, et al. . Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology 2005;42:44–52. doi:10.1002/hep.20734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:274–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:686–90. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. el-Karaksy HM, el-Koofy NM, Anwar GM, et al. . Predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese and overweight Egyptian children: single center study. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2011;17:40–6. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.74476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Zayadi A, Attia M, Barakat EM, et al. . Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with HCV genotype 4. Gut 2007;56:1170–1. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.123331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zaki ME, Ezzat W, Elhosar YA, et al. . Factors associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese adolescents. Maced J Med Sci 2013;6:273–7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3889/MJMS.1857-5773.2013.0311 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-hamoudi W, El-Sabbah M, Ali S, et al. . Epidemiological, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of Saudi patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a hospital-based study. Ann Saudi Med 2012;32:288–92. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2012.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hannoun Z, Lessan N, Barakat MT. High prevalence of elevated liver transaminases among 38 727 patients in a diabetes centre in the United Arab Emirates. Endocrine Abstracts 2013;32:363 doi:10.1530/endoabs.32.P363 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. . The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American association for the study of liver diseases, American college of gastroenterology, and the American gastroenterological association. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:811–26. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petta S, Muratore C, Craxì A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis: the present and the future. Dig Liver Dis 2009;41:615–25. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2009.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016;65:1038–48. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anstee QM, Day CP. The genetics of NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:645–55. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2013.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 2010;51:679–89. doi:10.1002/hep.23280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang JY, Kang AH, Green A, et al. . Systematic review: worldwide variation in the frequency of coeliac disease and changes over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:226–45. doi:10.1111/apt.12373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Green PH, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2003;362:383–91. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turnbull JL, Adams HN, Gorard DA. Review article: the diagnosis and management of food allergy and food intolerances. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:3–25. doi:10.1111/apt.12984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB, et al. . Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol 2011;29:493–525. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-040210-092915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. . The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med 2010;42:587–95. doi:10.3109/07853890.2010.505931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. . Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:286–29. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.3.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Volta U, Bellentani S, Bianchi FB, et al. . High prevalence of celiac disease in Italian general population. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46:1500–5. doi:10.1023/A:1010648122797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alessandrini S, Giacomoni E, Muccioli F. Mass population screening for celiac disease in children: the experience in Republic of San Marino from 1993 to 2009. Ital J Pediatr 2013;39:67 doi:10.1186/1824-7288-39-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ivarsson A, Myléus A, Norström F, et al. . Prevalence of childhood celiac disease and changes in infant feeding. Pediatrics 2013;131:e687–94. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greco L, Timpone L, Abkari A, et al. . Burden of celiac disease in the Mediterranean area. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4971–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i45.4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abu-Zekry M, Kryszak D, Diab M, et al. . Prevalence of celiac disease in Egyptian children disputes the east-west agriculture-dependent spread of the disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;47:136–40. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815ce5d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Medhat A, Abd El Salam N, Hassany SM, et al. . Frequency of celiac disease in Egyptian patients with chronic diarrhea: Endoscopic, histopathologic and immunologic evaluation. J Physiol Pathophysiol 2011;2:1–5. doi:10.5897/JPAP [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shalaby SA, Sayed MM, Ibrahim WA, et al. . The prevalence of coeliac disease in patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Arab J Gastroenterol 2016;17:73–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abd El Dayem SM, Ahmed Aly A, Abd El Gafar E, et al. . Screening for coeliac disease among Egyptian children. Arch Med Sci 2010;6:226–35. doi:10.5114/aoms.2010.13900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hariz MB, Laadhar L, Kallel-Sellami M, et al. . Celiac disease in Tunisian children: a second screening study using a "new generation" rapid test. Immunol Invest 2013;42:356–68. doi:10.3109/08820139.2013.770012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reilly NR, Lebwohl B, Hultcrantz R, et al. . Increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease after diagnosis of celiac disease. J Hepatol 2015;62:1405–11. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marciano F, Savoia M, Vajro P. Celiac disease-related hepatic injury: Insights into associated conditions and underlying pathomechanisms. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:112–9. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hastier A, Patouraux S, Canivet CM, et al. . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis and type 1 refractory celiac disease: More than a fortuitous association? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2016;40:4–5. doi:10.1016/j.clinre.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trovato GM, Trovato FM, Pirri C, et al. . NAFLD and celiac disease in adult patients. Faseb J 2011;25:30 doi:10.1096/fj.1530-6860 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abenavoli L, Milic N, De Lorenzo A, et al. . A pathogenetic link between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and celiac disease. Endocrine 2013;43:65–7. doi:10.1007/s12020-012-9731-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lo Iacono O, Petta S, Venezia G, et al. . Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with abnormal liver tests: is it always coeliac disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2472–7. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bakhshipour A, Kaykhaei MA, Moulaei N, et al. . Prevalence of coeliac disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arab J Gastroenterol 2013;14:113–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Borges VF, Diniz AL, Cotrim HP, et al. . Sonographic hepatorenal ratio: a noninvasive method to diagnose nonalcoholic steatosis. J Clin Ultrasound 2013;41:18–25. doi:10.1002/jcu.21994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. von Volkmann HL, Havre RF, Løberg EM, et al. . Quantitative measurement of ultrasound attenuation and hepato-renal index in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Med Ultrason 2013;15:16–22. doi:10.11152/mu.2013.2066.151.hlv1qmu2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A, et al. . Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology 2009;137:865–72. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, et al. . The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol 2006;6:33 doi:10.1186/1471-230X-6-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. . Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis 2010;42:503–8. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gaia S, Carenzi S, Barilli AL, et al. . Reliability of transient elastography for the detection of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis. J Hepatol 2011;54:64–71. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coeliac UK assessment tool. https://www.isitcoeliacdisease.org.uk/login?redirect=assessment (accessed 15 May 2017).

- 47. Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:129–34. doi:10.1007/BF01535722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Salgado AL, Carvalho L, Oliveira AC, et al. . Insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) in the differentiation of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and healthy individuals. Arq Gastroenterol 2010. 47:165–9. doi:10.1590/S0004-28032010000200009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Chourasia D, et al. . Lactose hydrogen breath test versus lactose tolerance test in the tropics: does positive lactose tolerance test reflect more severe lactose malabsorption? Trop Gastroenterol 2009. 30:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bao F, Bhagat G. Histopathology of celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2012;22:679–94. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PH, et al. . Larazotide acetate for persistent symptoms of celiac disease despite a gluten-free diet: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1311–9. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1513–24. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mouzaki M, Comelli EM, Arendt BM, et al. . Intestinal microbiota in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013;58:120–7. doi:10.1002/hep.26319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, et al. . Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009;49:1877–87. doi:10.1002/hep.22848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smarrazzo A, Misak Z, Costa S, et al. . Diagnosis of celiac disease and applicability of ESPGHAN guidelines in Mediterranean countries: a real life prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol 2017;17:17: 17 doi:10.1186/s12876-017-0577-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bizzaro N, Tampoia M, Villalta D, et al. . Low specificity of anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Lab Anal 2006;20:184–9. doi:10.1002/jcla.20130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Villalta D, Crovatto M, Stella S, et al. . False positive reactions for IgA and IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in liver cirrhosis are common and method-dependent. Clin Chim Acta 2005;356:102–9. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2005.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Villalta D, Girolami D, Bidoli E, et al. . High prevalence of celiac disease in autoimmune hepatitis detected by anti-tissue tranglutaminase autoantibodies. J Clin Lab Anal 2005;19:6–10. doi:10.1002/jcla.20047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bizzaro N, Villalta D, Tonutti E, et al. . IgA and IgG tissue transglutaminase antibody prevalence and clinical significance in connective tissue diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:2360–5. doi:10.1023/B:DDAS.0000007875.72256.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgast-2017-000150supp001.docx (59.5KB, docx)