Abstract

Aims

To report on the development and initial testing of a clinical tool, The Patient Preferences for Patient Participation tool (The 4Ps), which will allow patients to depict, prioritize, and evaluate their participation in health care.

Background

While patient participation is vital for high quality health care, a common definition incorporating all stakeholders' experience is pending. In order to support participation in health care, a tool for determining patients' preferences on participation is proposed, including opportunities to evaluate participation while considering patient preferences.

Methods

Exploratory mixed methods studies informed the development of the tool, and descriptive design guided its initial testing. The 4Ps tool was tested with 21 Swedish researcher experts (REs) and patient experts (PEs) with experience of patient participation. Individual Think Aloud interviews were employed to capture experiences of content, response process, and acceptability.

Results

‘The 4Ps’ included three sections for the patient to depict, prioritize, and evaluate participation using 12 items corresponding to ‘Having Dialogue’, ‘Sharing Knowledge’, ‘Planning’, and ‘Managing Self‐care’. The REs and PEs considered ‘The 4Ps’ comprehensible, and that all items corresponded to the concept of patient participation. The tool was perceived to facilitate patient participation whilst requiring amendments to content and layout.

Conclusions

A tool like The 4Ps provides opportunities for patients to depict participation, and thus supports communication and collaboration. Further patient evaluation is needed to understand the conditions for patient participation. While The 4Ps is promising, revision and testing in clinical practice is required.

Keywords: clinical tool, content validity, instrument development, patient participation, qualitative analysis

Introduction

Throughout the Western world, the last 50 years have shown a trend towards recognizing individuals' autonomy1 and today, most Western countries' legislations include references to patients' rights, including various aspects of ‘patient participation’. While the term ‘participation’ is ambiguous, earlier studies indicate that patients and health professionals may apply different perspectives to the concept of patient participation.2, 3 To support a common understanding of patient participation in clinical health‐care interactions, we propose a tool for patients to determine individual preferences with regard to participation, and opportunities to evaluate the experience of participation considering these preferences.

Background

In 1994, the World Health Organization, WHO, endorsed the declaration of patients' rights in Europe, advocating the promotion and sustaining of ‘beneficial relationships between patients and health‐care providers, and in particular to encourage a more active form of patient participation’.4 Not only does patient participation fuel patient autonomy, but also patient‐centred care and patient satisfaction, for example satisfaction with care.5, 6 While there are a number of concepts to promote different aspects of participation, such as patient empowerment,7 shared decision making8 and self‐management,9 the concept of participation itself is frequently applied in policies and legislations. In addition, patients' preferences for participation and/or effects of patient participation are continuously studied in health‐care research.10 Yet, the concepts of ‘participation’, and further, ‘patient participation’, offer a number of interpretations: ‘participation’ connotes ‘the action of partaking’, ‘taking part’, ‘associating’, or ‘sharing’ with others in some action or matter.11 More specifically, ‘participation’ can be ‘the involvement of members of a community or organization in decisions which affect their lives and work’.11 With a lack of lexical definitions of the term ‘patient participation’ in particular, the principal legislative definition corresponds to the latter, that is to say, patient participation as the involvement of a patient in decisions that affect his/her care and/or treatment. The origin of this interpretation is uncertain. Rather, over the years, a few concept analyses propose to clarify patient participation; in the early 1990s patient participation was suggested to involve ‘shared aims as well as shared desires between interactants’,12 suggesting that the health‐care giver and the health‐care receiver must have a common understanding as well as respect for each other's contribution. Later, Cahill compared patient participation with partnership, collaboration and involvement, presenting these in a hierarchical order, wherein involvement/collaboration is at the lowest level, participation mid‐level and partnership the highest level.13 Further, a more recent concept analysis in nursing defines patient participation as ‘an established relationship between nurse and patient, a surrendering of some power or control by the nurse, shared information and knowledge, and active engagement together in intellectual and/or physical activities’.14 Again, the analyses provide a diverse conception, as do health terminologies.15

Even before a common definition of patient participation has been agreed, health‐care staff are to provide conditions for patient participation in everyday health‐care interactions; for example, in Swedish health care, professionals are required to provide for patient participation by means of ‘individually adjusted information’, ‘the possibility to choose between different treatment alternatives’ and ‘the possibility for a second opinion’.16 Similar legislations exist in the other Nordic countries.17 Over the years, most efforts to evaluate patients' experiences of quality of care have included patient participation, mainly assessing the patient's view of their involvement in decision making, and in health care during the health‐care process and transition (e.g. Arnetz et al.18). However, our studies show that patients apply a wider notion to patient participation, defining the concept by comprehension, mutual communication, having and applying knowledge, and being confident.10 This signifies that patients' definition of participation is beyond decision making, implying a need for further efforts to promote patient participation in health care from a patient perspective. To support health‐care professionals to recognize patients' preferences for participation, there is a need for a tool that provides not only evaluation opportunities, but also the conditions for a dialogue on preferences in the initiation of a health‐care interaction. The aim of this article was to report on the development and initial testing of such a clinical tool, The Patient Preferences for Patient Participation tool (The 4Ps), which will allow patients to depict, prioritize and evaluate their participation in health care.

Methods

Design

While the tool for Patients Preferences for Patient Participation, called ‘The 4Ps’, originated from exploratory mixed methods,19 it was initially validated with regard to how researcher experts (RE) and patient experts (PE) experienced its content, the response process and acceptability20 employing qualitative design.21 In this study, ‘acceptability’ was defined as: if the tool is considered realistic (or not) to apply in clinical practice; if considered useful (or not) for dialogues on and evaluation of patient participation in clinical practice; and/or if considered of potential (or not) for promoting patient participation in clinical practice.

Development of The 4Ps tool

The structure and content of the tool

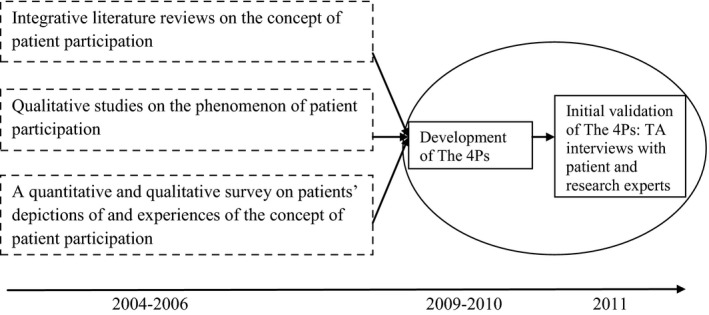

Although our earlier studies on patients' conceptualization of participation did not primarily aim for the development of a tool, the findings indicated that, to patients, a broader definition than merely participation in decision making applies to ‘patient participation’, and that there was more to the concept of patient participation than what was included in the prevailing instruments used at that point in Sweden.10 Thus, to support everyday health‐care interactions to provide conditions for patient participation, The 4Ps was created; the progress of the development to date outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the earlier studies underpinning the items of The 4Ps, the development of the tool, and the initial validation process; the parts marked by an oval are represented in this article.

To the patient informants of our earlier studies, an ordinary concept such as ‘patient participation’ seemed to be novel. Thus, a principal idea was for the tool to first provide for the individual to consider what patient participation means to him/her. The conceptualization process in The 4Ps was supported by suggested items, to be chosen according to the individual patient's understanding of ‘patient participation’. The basics of these items were identified in two qualitative studies on the phenomenon of patient participation in patients with chronic heart failure,3, 22 a survey on adult somatic health‐care patients' experience of patient participation,15, 23 and two parallel integrative literature reviews.10 Secondly, the tool should incorporate a section for the patient to define the importance of the different items of participation for his/her upcoming health‐care interaction, that is to define preferences for patient participation.24 Lastly, the tool was to include a section for the patient to evaluate to what extent he/she had experienced patient participation.

All three sections were designed to include the same predefined items of patient participation; those identified in earlier studies on what patients describe as participation suggested in relation to different aspects of patient participation found in our studies,10 the latter presented as headings to each cluster of items.

The tool was created in order for the two first sections to be shared by the patient with the health‐care professionals, to provide for a common understanding by patient and health‐care staff of the patient's idea of and preferences in terms of participation in a particular situation and health‐care interaction. Thus, those sections could be kept within the patient's record until the evaluation. The third section was intended to be completed after some health‐care interactions or a period of time, to be decided by the organization applying the tool. Overall, the tool had guidance on how to proceed when completing the tool and how and when to complete the three different sections.

The rating scales for patient's prioritization and evaluation

The first section, on depicting patient participation, included no rating scale, but the patient ticks the or those of the suggested items (if any). For the rating in section 2, where the patient prioritizes to what extent each item is important to experience patient participation, a 4‐point Likert scale was suggested, ranging from ‘Completely unimportant’ to ‘Very important’ per item. For section 3, where the patient was asked to evaluate to what extent he/she had experienced patient participation using the same 12 items (phrased in past tense), each item came with a 4‐point Likert response scale, ranging from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Completely’.25 The Likert scales were a pragmatic choice: they are commonly used in patient surveys in Sweden (e.g. Arnetz et al.18, Arnetz and Arnetz26, Wilde et al.27), and thus possibly familiar to patients, and a 4‐point scale was suggested to provide for health‐care professionals to easily capture and understand, as the tool was suggested to provide for: (i) a dialogue on the patient's priority in terms of participation (section 2), and (ii) the patient's evaluation of the participation (section 3).

Sample and procedure for testing The 4Ps tool

The 4P's tool was subject to TA‐interviews among experts purposefully sampled for having experience of patient participation from either research or clinical interactions;28 we identified Swedish health‐care researchers who during the last 10 years had published studies on patient participation, or related issues such as: communication in health‐care interactions; shared decision making; and tools on quality of care including patient participation. All had their background in various health professions. Further, we recruited laypersons of different sex and age, all being able to communicate in Swedish, who had been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and/or chronic heart failure (CHF) and thus had experience of being in the patient role and of self‐care. Consequently, they were considered to be PEs;28 PEs with COPD and/or CHF was a pragmatic choice as The 4Ps was proposed for evaluating a later intervention in this group of patients. The PEs were identified within a Swedish county including a city, towns and rural areas, and thus representative of the country. The PEs were identified through either their specialist nurse for COPD or CHF in primary care, or by the head of the local Swedish Heart and Lung Association, respectively; these contacts suggested persons adhering to the above criteria to the research team, providing names and addresses. Both REs and PEs were contacted via mail with information about the study, and within 1–2 weeks a researcher on the team contacted them, and asked if willing to partake in an individual study interview. Of the 30 experts contacted (11 REs and 19 PEs), 10 REs and 11 PEs consented to partake. The final PEs participating were six men and five women, 56–77 years of age (mean: 66 years). They were diagnosed with either COPD (n = 6) or CHF (n = 5) and had known about their diagnosis between 1 month and 14 years prior to the TA‐interview, and thus considered representative for the patient groups.

Data collection and data analysis

To test The 4Ps, individual TA‐interviews with REs and PEs were performed in early 2011.21 Pilot interviews with two REs and four PEs suggested TAs suitable yet indicated a need for REs to have further information on how the tool was to be used in practice prior to the TA, and for PEs, more probes to keep thinking aloud. All study interviews were carried out by the same researcher (KL), and followed a set structure; each TA‐interview was initiated by information on the purpose of the interview and how to proceed, that is, to consider The 4Ps while thinking aloud. The participant had two trial questions on everyday issues, to set the participant's mind on continuously phrasing what he/she read and what he/she thought when reading, and sharing the thinking and reflections made. Next, the expert was handed The 4Ps, reminded that the interview was about The 4Ps, and encouraged to think aloud whatever came to mind while considering the tool. The interviewer only interacted to remind the expert to think aloud and to phrase probing questions when necessary, such as: ‘do you have any further thoughts on that?’ In the interviews, lasting between 31 and 60 min (mean 46 min), the respondents considered the entire tool at once. All TA‐interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim for later analysis.

Qualitative content analysis29 was conducted: The analysis was initiated by the 21 transcribed interviews being read through to get a sense of the data and the whole. As most experts were found to have considered The 4Ps in correspondence with the structure of the tool, that is, the section 1, 2 and 3 in succession, including content and layout, an unconstrained matrix was formed. The matrix included: (i) the concept of patient participation in general, (ii) the four aspects of patient participation presented, (iii) the 12 items of patient participation organized by three for each aspect, (iv) missing items or aspects, (v) layout, (vi) instructions, (vii) items' response scales, (viii) response process and (ix) acceptability. Next, each interview was read repeatedly, identifying all meaning units corresponding to the matrix. Advancing the analysis, meaning units were formed into subcategories, guided by the essence of the meaning units. Subsequently, the subcategories were formed into categories, corresponding to the aim of the TA‐test that is, experts' experience of The 4Ps’ content validity, the response process and the acceptability of the tool. To support trustworthiness of the analysis, two authors (KL and ACE) performed the analysis separately, informing the dialogue in the ongoing analysis until agreement.

Ethics

The validation study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Uppsala, Sweden (number 2011/032). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their TA‐interview.

Findings

The 4Ps tool as presented to the researcher and patient experts

The version of The 4Ps tool used in this study consisted of three sections: for (1) depicting, (2) prioritizing and (3) evaluating patient participation. Section 1 was where the patient was instructed to tick the, or those of, 12 items that convey his or her idea of patient participation. The 12 predefined items were organized three by three in four aspects of patient participation: ‘Having Dialogue with Health Care Staff’, ‘Sharing Knowledge’, ‘Partaking in Planning’ and ‘Managing Self‐care’. The aspects and items applied in The 4Ps tool used in the study are presented in Table 1, along with the source of each item. In the second section, the patient was asked to prioritize the 12 items of ‘patient participation’, suggesting how important he/she considers each item to be in the approaching health‐care interaction. The third and final section of the tool included the opportunity for the patient to assess to what extent he/she had experienced patient participation, again using the same 12 items (Table 1).

Table 1.

The items included in the trial version of The 4Ps tool, with the corresponding aspects of patient participation, and sources

| Item order | Aspects | Items | Source of items |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Having dialogue with health‐care staff | There are conditions for mutual communication | 15, 23 |

| 2 | My knowledge and preferences are respected | 15, 22 | |

| 3 | Health‐care staff listen to me | 15, 22, 23 | |

| 4 | Sharing knowledge | I get explanations for my symptoms/issues | 15, 22, 23 |

| 5 | I can tell about my symptoms/issues | 15, 23 | |

| 6 | Health‐care staff explain the procedures to be performed/that are performed | 23 | |

| 7 | Partaking in planning | Knowing what is planned for me | 23 |

| 8 | Taking part in planning of care and treatment | 23, 26, 48 | |

| 9 | Phrasing personal goals | 22, 41 | |

| 10 | Managing self‐care | Performing some care myself, like e.g. managing my medication or changing dressing | 22, 23, 49 |

| 11 | Managing self‐care, like e.g. adjusting diet or performing preventive health care | 22, 23, 49 | |

| 12 | Knowing how to manage my symptoms | 15, 22, 23 |

Researchers' and patient experts' validation of The 4Ps tool

The Researchers' and patient experts' experiences of The 4Ps was concluded as: ‘The 4Ps tool essentially mirrors the concept of patient participation and it may facilitate patient participation in clinical practice among patients with chronic conditions, while revision is needed for comprehensibility, and to better target patients' experience of their condition’. All categories and their corresponding subcategories sustaining the conclusion are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Subcategories and categories from the analysis of the TA‐interviews with researchers (REs) and patient experts (PEs) on The 4Ps tool

| Subcategories | Categories | Primarily illustrating validity aspect |

|---|---|---|

| The concept of patient participation is captured in the aspects and the items | Aspects and items reflect the concept of patient participation; it is crucial that examples target patients' experiences; propose an opportunity to provide additional aspects | Content validity |

| The aspects and the items of the tool are relevant | ||

| The items are essential for a tool on patient participation | ||

| The items capture reciprocity, which is crucial for patient participation | ||

| Participation a main thread throughout the tool | ||

| The items are prerequisites for patient participation | ||

| An open‐ended option to define additional aspects of patient participation is wanting (REs only) | ||

| The self‐care examples are not related to COPD or CHF | ||

| Difficult to relate to items' with limited content | ||

| Items illustrating what one has not experienced are challenging (PEs only) | ||

| The aspects and items are discrete | Aspects and items are easy to understand when phrased in everyday language and each includes one perspective only | Content validity |

| The phrasing of the aspects and items makes them easy to understand | ||

| Items not phrased in everyday language difficult to understand | ||

| Item perceived to contain two issues is ambiguous | ||

| The content of some items may be abstract for patients (REs only) | REs expect patients to have needs and trouble understanding the content of and level of complexity of the tool that PEs do not demonstrate or describe | Content validity |

| Participation requires reciprocity, lacking in some items (REs only) | ||

| Examples of self‐care and own goals related to experiences provided (PEs) | ||

| Patients should have opportunity for a next of kin to answer the tool as proxy (REs only) | ||

| The phrasing of some items not in everyday language (REs only) | ||

| The aspects ‘Having a dialogue’, ‘Partaking in planning’ and ‘Managing self‐care’ are equally related to the aspect ‘Sharing knowledge’ | Items relate to their corresponding aspect; some aspects lack logic of the items' order | Content validity |

| Items in the aspects related | ||

| Items in the aspects ‘Having a dialogue’, ‘Sharing knowledge’, and ‘Managing self‐care’ lack logical order | ||

| Appealing design and format of the tool | The structure and layout is appealing but aspects categorizing the items create confusion | Response process |

| Confusing that each section is divided into four parts with aspects of patient participation as headings | ||

| The introduction is relevant and clear | The instructions are relevant and easy to understand when phrased in consistent, everyday language | Response process |

| The instructions for the tool and each section are relevant and clear with an intuitive phrasing | ||

| The same phrasing should be used consistently in the instructions | ||

| If not phrased in everyday language, instructions are not easy to understand | ||

| The verbal scales (section 2 and 3) easy to understand, and possible to consider the items using them | The scales are easy to consider, but a response alternative is lacking | Response process |

| The alternatives in the scales (section 2 and 3) are relevant and clear | ||

| One option in section 3 does not fit all items | ||

| The scales (section 2 and 3) have irregular intervals | ||

| Because of supreme end values, there is a risk that the whole scale will not be used (section 2 and 3) (REs only) | ||

| An option stating that an item is not applicable is lacking (section 2 and 3) | ||

| The tool is distinct and understandable | The tool is easy to respond to, but sections 1 and 2 are duplicates | Acceptability |

| Confusing to consider the entire tool when suggested for different points of time | ||

| The number of issues in the tool is manageable | ||

| The tool is easy to respond to | ||

| It is quick and easy to complete the tool | ||

| The tool is responded to as intended | ||

| Section 1 of the tool, where the patient is to define patient participation, can be evaluation of previous health care contact | ||

| To consider items twice consecutively, in section 1 and 2, is a duplication | ||

| Section 2, where the patient prioritize patient participation is relevant | ||

| The change of wording and tenses in the evaluation (section 3) confusing when considering all three sections together | ||

| Valuable that patient participation can be evaluated by patients | The tool can facilitate participation in patient – staff interactions in health care, if obvious which health care contact it refers to and the evaluative section is not part of the patient's record | Acceptability |

| The tool is relevant for patient participation in clinical use | ||

| After a period of time/series of health‐care interactions, patients can re‐respond to the tool based on new experiences | ||

| The content of the tool provides for sincere responses | ||

| The tool is appealing to respond to in one's health care contact | ||

| A risk for unreliable answers if the evaluation (section 3) becomes part of the patient's record | ||

| A clear timeframe for when to complete the evaluation (section 3) is necessary |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The 4Ps tool was considered to be relevant and patients are likely to be sincere in their responses in a health‐care setting they regularly visit. Further, it was perceived valuable that patients get an opportunity to depict their participation, and of importance that patient participation is evaluated. The tool was considered to be useful for health‐care teams and suitable to be applied intermittently in clinical practice.

The items suggested in the tool were perceived to accurately depict the categories of patient participation. Rather, both REs and PEs considered items indispensable in a patient participation tool were included. PEs and REs considered the items easy to understand. While most items were considered to be phrased in an intuitive language and therefore easily understandable, two items were identified as needing revision: one item on preferences considered including two issues, and one not clearly linking to the patients' individual care. Both REs and PEs perceived the term ‘knowledge’ as one not being commonly used by laypeople but instead by professionals, and suggested that the term ‘information’ was lacking in the tool.

Despite agreement on most items, having them organized three by three with their corresponding aspects was considered to be confusing; the aspects were interpreted as headings and made the respondents uncertain about whether one, two or all items could be ticked, regardless of the instructions.

In general, the instructions were considered to be relevant, understandable and phrased in lay language even though single words were considered to be difficult to interpret, such as ‘preferences’, and some sentences were thought to be too long. Inconsistent wording was identified (e.g. ‘to be participating’ vs. ‘to experience participation’, and ‘being involved as a patient’ vs. ‘involvement in care’). In particular, the section 3 instructions needed clarification, to explain that this was a later evaluation. While the REs and PEs considered the entire tool at one point (rather than as suggested, i.e. section 1 and 2 separately, and section 3 later), they found the alterations in tense confusing.

In terms of comprehending the items, the REs further suggested that items such as ‘performing self‐care’ might be distressing for patients and that ‘setting one's own goal’ would be unfamiliar to patients. Conversely, the PEs did consider these aspects to be familiar, and suggested that they do perform these aspects of patient participation in their role as patients; PEs provided examples of themselves setting goals, on their own or in collaboration with the health‐care staff, including long‐term goals such as altered lifestyle (e.g. smoking cessation). Some examples provided in the managing self‐care item, such as ‘modify my diet’, were considered relevant, while examples in terms of performing care myself, like ‘change dressing’, were not. Rather, the PEs gave examples of preventive health care and symptom management, related to their own experience of CHF and/or COPD. The one item PEs shared having trouble relating to was ‘participation in planning’ where they lacked or had limited experience. The item ‘to get explanations for my symptoms’ was considered to be limited; despite the absence of the identification of any single medical explanation for a symptom, knowledge exchange (being an aspect of participation) can take place. Further, REs and PEs suggested that not only do examinations need explanations, but also other health‐care procedures.

REs and PEs considered all three items for ‘having a dialogue’, ‘sharing knowledge’ and ‘managing self‐care’, respectively, relevant for their corresponding aspect. Yet, the items in these aspects were not presented in the most logical order (as they were in ‘partaking in planning’). Further, the response scales were considered to be relevant, easy to understand and easy to use. However, the REs suggested including a fifth response alternative, such as ‘not relevant’. The REs also suggested assuring consistency of the intervals.

In general, the REs and PEs considered the tool to be attractive, with its limited number of sections and items. In particular, the PEs experienced the tool to be easy and quick to complete. To define what patient participation is, in section 1, and then to indicate how important each item is in section 2 was considered to be repetitive. Section 2 alone was considered to be relevant, and it was considered to be important to provide an opportunity to share what one as a patient depicts as preferred aspects of participation.

Discussion

While patient participation remains a vital aspect of high quality health‐care interactions,4 a common definition including all stakeholders is pending. Concept analyses suggests the inclusion of different perspectives,12, 13, 14, 30 but only a few studies have investigated what patients define as and expect in terms of participation in health care.10 Rather, most have focused on decision making (e.g. Heggland et al.31). While the notion of, for example, ‘shared decision‐ making’ corresponds to the origin of patient participation, that is, autonomy as ‘the exercise of considered, independent judgement to effect a desirable outcome’,32 it is not the only way to interpret ‘patient participation’ in particular.15 Rather, the way patients depict participation corresponds to, for example, the ICF definition, as the ‘involvement in a life situation’, including learning and applying knowledge, communication, self‐care and interpersonal interactions.33

In this study, a core that includes qualitative and quantitative studies and literature reviews was used as a base for the initial version of the patient participation tool, ‘The 4Ps’, adding also patients' perspectives to the concept. Further, we used both researcher and patient experts to test the content, response process and acceptability of the tool.20 The findings suggest The 4Ps tool to be relevant and comprehensible on the whole, as well as a valuable addition for clinical practice to provide for and evaluate patient participation. Yet, there were aspects of the tool, both by content and by layout, found to require revision.

While our earlier studies indicated that dwelling on one's experience of the phenomenon patient participation helped participants to depict the concept (e.g. Eldh et al.22), the REs and PEs shared that the benefit of being able to conceptualize participation while at the same time determining the importance of each item to the process of patient participation was overlooked. An earlier survey applying items to depict patient participation and non‐participation suggested that the item format could be appropriate for a clinical tool. Meanwhile, in, the two sections on depiction and prioritizing, respectively, applying the same 12 items was considered to be iteration, calling for revision of The 4Ps.

Both PEs and REs expected The 4Ps to facilitate patient participation in health‐care interactions because of the correspondence between items and the concept of patient participation; even with a need for some rephrasing and better correlation between examples and the experiences of the target group, the items were considered to be relevant. However, more context‐specific examples should be included in the tool to acknowledge the extensive knowledge of people affected by a long‐term condition (e.g. Ref. 34). This would supposedly provide a more relevant tool corresponding to the target patient groups; in this study, The 4Ps was tested for patients with COPD and/or chronic heart failure (CHF).

Again, both REs and PEs applied a broader definition to ‘patient participation’ than the common, legislative aspect, which focuses on partaking in decision making. It is notable how the idea of patient participation has been pointed towards decision making – and the lack of clarity as to the origin of this interpretation; particularly as the experience of being faced with a decision‐making situation as a patient can be perceived as non‐participation.35 While a growing number of studies stress the ‘shared decision‐making’ aspect of participation, it seems that the ‘sharing’ aspect of decision making is vital. In addition, the process preceding a decision‐making situation provides conditions for other aspects of patient participation: by sharing knowledge and paying respect to both the health professional's and the patient's contributions to the dialogue.23

While PEs and REs considered all items in The 4Ps to be essential elements of patient participation and that they correspond with ‘having a dialogue’, ‘sharing knowledge’, ‘partaking in planning’ and ‘managing self‐care’, they suggested that ‘information’, in addition to knowledge, should be included in the tool. Communication and participation has been found to be linked,36 and the information process is a vehicle for communication.37 Our understanding is that the relationship is reciprocal: communication, including information sharing, is fundamental for participation, just as sharing knowledge is also essential for shared decision making.38 The knowledge of patients affected by long‐term conditions is extensive, and self‐care is shown to be essential and a key factor of quality care (e.g. Jeon et al.34). Even though self‐care, as well as sharing information, has been found to be an aspect of participation from a patient perspective,22 little is known about what promotes communication on self‐care and other aspects of participation.39 Further, the managing self‐care aspect is central to and corresponds with participation, adding to the conceptual aspect of patient participation as suggested, for example, in the ICF.33

Although REs and PEs agreed that the items in The 4Ps represented patient participation, some differences were detected between the two expert groups: The PEs, being laypeople with experience of being in the patient role due to chronic heart or pulmonary disease, not only considered most items to be uncomplicated, but they also provided extended suggestions as to how and what goals they set for themselves, an item the REs doubted that the patients would recognize; while PEs provided examples of, for example, self‐care, suggesting that this is an aspect of participation, the REs suggested this item might be puzzling for patients. Ill‐health has been suggested to be a serious threat to autonomy,40 yet our findings also remind us that the perceptions and values of health‐care professionals may also affect the health‐care interaction.

Further, the act of setting and sharing individual health‐care goals correspond to aspects of participation as shared aims, one of the initial notions of patient participation.12 In addition, earlier studies have shown that setting common goals supports the collaboration between patient and health professional and maximizes the possibility that the patient will achieve those goals.41 We suggest that successful collaboration requires mutual respect for one another and the distinctive knowledge brought into the interaction by both patients and health professionals. This corresponds with a more recently introduced concept in health care: person‐centred care. Person‐centred care suggests that care should be underpinned by values of respect for persons, individuals' right to self‐determination, and mutual respect and understanding.42 Further, person‐centred care includes the process of decision making.43 For our study, the one item that the PEs did not recognize from their own experiences was the shared planning; a finding possibly mirroring the fact that health professionals do not take the opportunity to involve patients in a dialogue on what should or needs to be done for the individual. However, setting goals was seen to be more problematic by patients with CHF than COPD, possibly as an effect of the variation and unpredictability of the disease.34 This finding emphasizes the necessity of adhering to patient groups and individuals when reflecting on what patient participation may mean, but also illustrates the need for further testing of The 4Ps to better understand which aspects of patient participation are relevant in different health‐care interactions and according to what needs.

‘Patient participation’ is just one aspect of what constitutes health‐care interactions of high quality. Is a tool to measure patient participation in particular then necessary? This study suggests that The 4Ps tool will support patient participation in clinical practice, though further testing is necessary. A recent report from Swedish health care emphasizes the continuing need to improve opportunities for knowledge sharing and patient‐centred care44 and an earlier study among surgical care patients suggest that a tool to raise issues considered important to them as individuals is useful in the dialogue, particularly with the registered nurses.45 Despite the availability of valid questionnaires in Swedish for measuring patients' perceptions of their involvement during hospitalization for myocardial infarction care,18 and for patient participation in emergency departments,46, 47 respectively, ‘The 4Ps’ is innovative in providing both an opportunity for the patient to prioritize aspects important to experience patient participation, and, at a later occasion, evaluate the same aspects of patient participation that the patient has experienced.

Limitations

The Swedish context provided a limitation in terms of the number of available researchers on patient participation. Rather, not all REs had their entire focus on patient participation and thus, the input provided was somewhat diverse. Yet, presenting The 4Ps tool to international researchers would have required a translation and validation of the tool in English considered to be beyond the scope of the initial testing. Further, while the TA‐technique has being proposed as an appropriate method for qualitative testing of instruments,21 the structure of the tool did impact on the TA‐interviews; given the findings, the interviews could have benefited from more follow‐ups on the experts' ideas of improving the tool. In addition, further psychometric testing of The 4Ps tool is needed, along with future studies on potential overlap between this tool on patient participation and measures of related concepts, such as patient‐centred care and shared decision making. Further, before employing The 4Ps tool in other groups of patients than people suffering from CHF and/or COPD, additional testing is essential.

Conclusion

Patient participation remains a vital aspect of high quality health‐care interactions, both from a policy and stakeholder perspective. Yet, a common definition of patient participation also including patients' experiences is pending. In this study, we found ‘The 4Ps’ considered to be a useful tool which most likely will reinforce quality in health‐care interactions, while supporting patients to depict, prioritize and evaluate patient participation, of relevance for Swedish health care and beyond. The development and testing of ‘The 4Ps’ contributes to the progress of better understanding the concept of participation, confirming that both researcher and patient experts agreed that the items did correspond to aspects of participation, such as ‘Having Dialogue with Health Care Staff’, ‘Sharing Knowledge’, ‘Partaking in Planning’ and ‘Managing Self‐care’. However, the structure, layout and phrasing of The 4Ps tool needs some revision, and further testing is necessary.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contribution

ACE developed the tool, supervised the validation study, and drafted and revised the manuscript. KL carried out the validation data collection, analysis and reporting, and contributed to the revision of the paper. ME provided intellectual input to the development of the tool and to the manuscript.

Funding

The development of the tool was carried out with the support of a planning grant in 2008 from the Capio Research Fund, Sweden. The validation study was carried out as a part of a doctoral student's research, supported by the Family Medicine Research Centre, Örebro county council.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Professor I. Ekman, the Sahlgrenska Academy at Goteborg's University, Sweden, for valuable input to the development of the tool on patient participation.

References

- 1. Rothman DJ. The origins and consequences of patient autonomy: a 25‐year retrospective. Health Care Analysis, 2001; 9: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Florin J, Ehrenberg A, Ehnfors M. Patient participation in clinical decision‐making in nursing: a comparative study of nurses' and patients' perceptions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2006; 15: 1498–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eldh AC, Ehnfors M, Ekman I. The meaning of patient participation for patients and nurses at a nurse‐led outpatient clinic for chronic heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2006; 5: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . A Declaration on the Promotion of patients' Rights in Europe. Amsterdam: WHO Regional Office for Europe, WHO, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision‐making and evidence‐based practice. Community Mental Health Journal, 2006; 42: 87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dijkers MP. Issues in the conceptualization and measurement of participation: an overview. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2010; 91: S5–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson MO. The shifting landscape of health care: toward a model of health care empowerment. American Journal of Public Health, 2011; 101: 265–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xie B, Wang M, Feldman R, Zhou L. Internet use frequency and patient‐centered care: measuring patient preferences for participation using the health information wants questionnaire. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2013; 15: e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hook ML. Partnering with patients–a concept ready for action. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2006; 56: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eldh AC. Patient Participation – What it is and What it is not [Doctoral thesis]. Örebro: Örebro university, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simpson JA, Weiner ESC. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edn Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ashworth P, Longmate M, Morrison P. Patient participation: its meaning and significance in the context of caring. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1992; 17: 1403–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cahill J. Patient participation: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1996; 24: 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sahlsten M, Larsson I, Sjöström B, Plos K. An analysis of the concept of patient participation. Nursing Forum, 2008; 43: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eldh AC, Ekman I, Ehnfors M. A comparison of the concept of patient participation and patients' descriptions as related to health care definitions. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 2010; 21: 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Socialstyrelsen . Din Skyldighet att Informera och Göra Patienten Delaktig – Handbok för Vårdgivare, Verksamhetschefer och Personal [Your Obligation to Inform and Make the Patient Participate – Handbook for Health Organisations, Managers, and Professionals]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fallberg LH. Patients rights in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Health Law, 2000; 7: 123–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arnetz JE, Höglund AT, Arnetz BB, Winblad U. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for measuring patient views of involvement in myocardial infarction care. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2008; 7: 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd edn New York: Sage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The American Educational Research Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education . The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Quality of Life Research, 2003; 12: 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eldh AC, Ehnfors M, Ekman I. The phenomena of participation and non‐participation in health care: experiences of patients attending a nurse‐led clinic for chronic heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2004; 3: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eldh AC, Ekman I, Ehnfors M. Conditions for patient participation and non‐participation in health care. Nursing Ethics, 2006; 13: 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 1997; 29: 21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilson M. Constructing Measures: An Item Response Modeling Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arnetz J, Arnetz B. The development and application of a patient satisfaction measurement system for hospital‐wide quality improvement. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1996; 8: 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilde LB, Larsson G. Development of a short form of the Quality from the Patient's Perspective (QPP) questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2002; 11: 681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marshall MN. The key informant technique. Family Practice, 1996; 13: 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2008; 62: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ashworth PD. The meaning of participation. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 1997; 28: 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heggland LH, Mikkelsen A, Ogaard T, Hausken K. Measuring patient participation in surgical treatment decision‐making from healthcare professionals' perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2014; 23: 482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keenan J. A concept analysis of autonomy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1999; 29: 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jeon YH, Kraus SG, Jowsey T, Glasgow NJ. The experience of living with chronic heart failure: a narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Services Research, 2010; 10: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eldh AC, Ekman I, Ehnfors M. Considering patient non‐participation in health care. Health Expectations, 2008; 11: 263–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Farin E, Gramm L, Schmidt E. The congruence of patient communication preferences and physician communication behavior in cardiac patients. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 2011; 31: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kasper J, Légaré F, Scheibler F, Geiger F. Turning signals into meaning – ‘Shared decision making’ meets communication theory. Health Expectations, 2011; 15: 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siminoff LA, Ravdin P, Colabianchi N, Sturm CM. Doctor‐patient communication patterns in breast cancer adjuvant therapy discussions. Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Protheroe J, Blakeman T, Bower P, Chew‐Graham C, Kennedy A. An intervention to promote patient participation and self‐management in long term conditions: development and feasibility testing. BMC Health Services Research, 2010; 10: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones H. Autonomy and paternalism: partners or rivals? British Journal of Nursing, 1996; 5: 378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wressle E, Eeg‐Olofsson AM, Marcusson J, Henriksson C. Improved client participation in the rehabilitation process using a client‐centred goal formulation structure. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2002; 34: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C et al Person‐centered care – ready for prime time. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2011; 10: 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCance T, McCormack B, Dewing J. An exploration of person‐centredness in practice. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 2011; 16: 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Antemar G. Mer Patientperspektiv i Vården – Är Nationella Riktlinjer en Metod? [More Patient Perspective in Health Care – Are National Guidelines a Way?] Stockholm: Riksrevisionen, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jangland E, Carlsson M, Lundgren E, Gunningberg L. The impact of an intervention to improve patient participation in a surgical care unit: a quasi‐experimental study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2012; 49: 528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frank C, Asp M, Fridlund B, Baigi A. Questionnaire for patient participation in emergency departments: development and psychometric testing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2010; 67: 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Frank C, Fridlund B, Baigi A, Asp M. Patient participation in the emergency department: an evaluation using a specific instrument to measure patient participation (PPED). Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2011; 67: 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Författningssamling S. Hälso‐ och Sjukvårdslag [Swedish Health Care Act]. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ehnfors M, Ehrenberg A, Thorell‐Ekstrand I. Nya VIPS‐Boken. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2013. [Google Scholar]