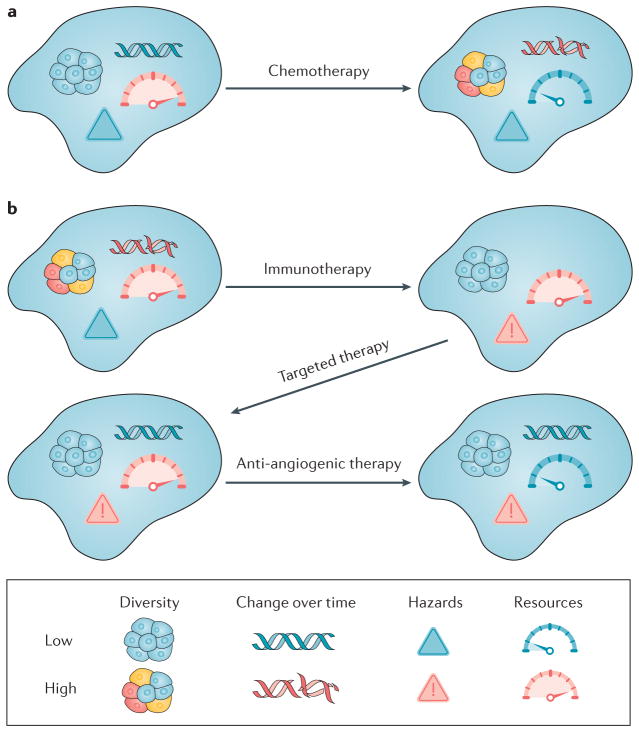

Figure 4. Changing the evolutionary class of a tumour through interventions.

With the classification system outlined in TABLE 2, we could examine how different interventions move tumours between categories. a | In this example, chemotherapy can be mutagenic and can select for hypermutator clones, generating new clones and more diversity40,186,187. It can also kill endothelial cells and thus have an anti-angiogenic effect188, resulting in a tumour (type 13) with one of the worst predicted prognoses. This may partly explain why tumours that recur after chemotherapy are so difficult to control. b | Immunotherapy, if successful, may increase the predation hazards to the tumour and perhaps select for a subclone, reducing diversity. Targeted therapy, unlike chemotherapy, probably does not cause significant DNA damage and may further genetically homogenize the tumour. Anti-angiogenic therapy is designed to restrict the resources of the tumour. At the end of this example sequence, the tumour is in the most manageable, least evolvable category (type 3 in TABLE 2). Of course, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy may have different effects depending on the details of those therapies and their interaction with the clones in the tumour and their ecosystem.