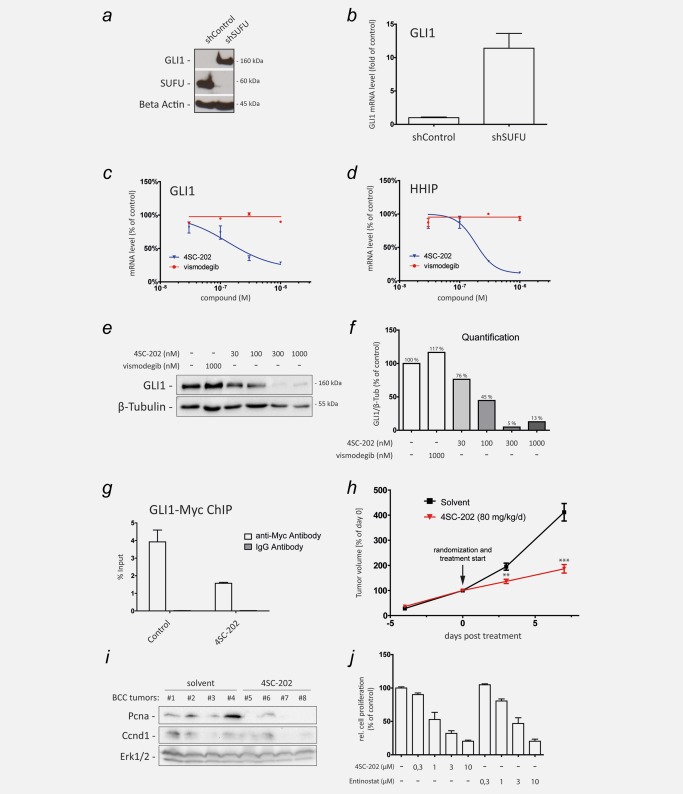

Figure 3.

4SC‐202 inhibits HH/GLI signaling in SMOi‐resistant cancer cells. (a) Western blot analysis of GLI1 expression in cells with lentiviral shRNA‐mediated knockdown of SUFU (shSUFU) or control knockdown (shControl). Beta Actin served as loading control. (b) qPCR analysis of GLI1 mRNA expression in SUFU knockdown (shSUFU) and control cells (shControl) transduced with lentiviral nontargeting scrambled shRNA. (c and d) qPCR analysis of GLI1 (c) and HHIP mRNA expression (d) as readout for HH/GLI signaling activity in SUFU‐depleted SMOi‐resistant cells showing resistance to vismodegib but sensitivity to 4SC‐202 treatment. (e) Western blot analysis of SUFU‐depleted Daoy cells treated with vismodegib or 4SC‐202 at the concentrations indicated. β‐Tubulin served as loading control. Vismodegib was unable to reduce GLI1 protein levels, while 4SC‐202 treatment effectively abolished GLI1 protein expression. (f) Relative densitometric quantification of GLI1/β‐Tubulin protein levels shown in (e). (g) ChIP analysis of MYC‐tagged GLI1 binding to the GLI target promoter PTCH in response to control or 4SC‐202 treatment. Enrichment of GLI1 bound promoter DNA was measured by qPCR. IgG isotype antibody was used as control. (h) Murine BCC cells were subcutaneously injected into dorsal flanks of 12 NSG mice. 4SC‐202 was administered by oral gavage at 80 mg/kg/day. The tumor volume at day 0 (i.e., start of drug treatment (arrow)) was set to 100%. (i) Western blot analysis of solvent (allografts #1–#4) and 4SC‐202 treated (allografts #5–#8) BCC lysates probed for proliferation‐cell‐nuclear‐antigen (Pcna) and Ccnd1 expression. Erk1/2 expression served as loading control. (j) Analysis of in vitro cell proliferation of murine BCC cells in response to 4SC‐202 and entinostat treatment. ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.