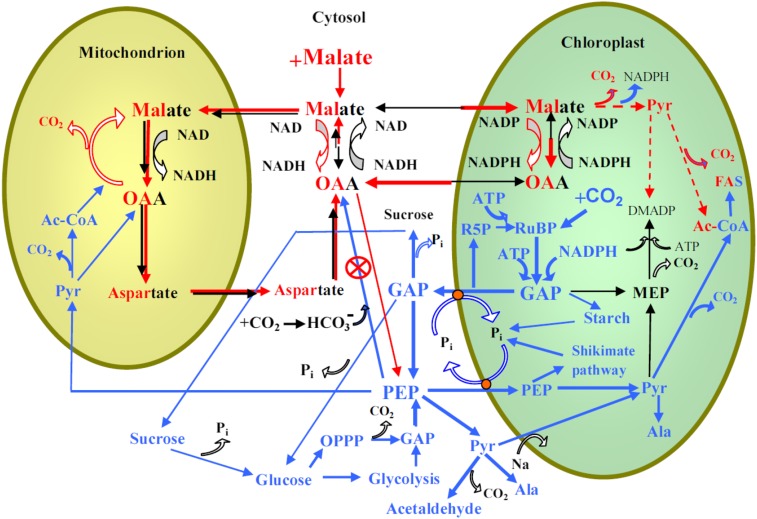

Figure 6.

Postulated scheme of the relationships between cytosolic, chloroplastic, and mitochondrial processes as affected by exogenous feeding by malate and increases in CO2 concentration. The processes enhanced by malate feeding are shown by red lines, whereas the thickness of the lines corresponds to the proposed magnitude of fluxes. Mixed red and black fonts denote compound pools affected by malate feeding. The processes suggested to be involved in the responses of photosynthesis and isoprene emission to the rise in CO2 (Fig. 1) are shown by blue lines, and the corresponding compound pools are shown by blue font. The action of PEPC-specific inhibitors such as DOA used in our study (Fig. 5) is also shown. The key effect of exogenous malate is the reversal of the malate-OAA shuttle such that the chloroplast reductive status increases. This leads to feedback inhibition of photosynthetic electron transport, ultimately suppressing net assimilation (Table I) and isoprene emission rates due to curbed DMADP pool size (Table II). The cytosolic PEP pool size is determined by PEP formation from GAP, its export to chloroplasts and mitochondria, and carboxylation to OAA by PEPC. Cytosolic GAP can originate from chloroplasts or be formed via glycolysis or via the oxidative pentose phosphate cycle (OPPP). Malate accumulation in cytosol enhances OAA concentration, curbing PEPC activity and enhancing cytosolic PEP pool size and transport into chloroplast. The activation of NADP+-malic enzyme in malate-fed leaves can further increase chloroplastic pyruvate (Pyr) concentrations, and cytosolic pyruvate can also be transported directly to chloroplast via an Na-dependent carrier (Furumoto et al., 2011). Enhanced dark and light respiration in malate-fed leaves is associated with both greater mitochondrial respiratory substrate availability and increased release of CO2 due to chloroplastic processes positively affected by malate feeding, including increased malic enzyme activity and fatty acid synthesis. Malate-feeding (Table II; Fig. 3) and DOA-feeding (Fig. 4) experiments indicate that cytosolic PEP availability cannot curb isoprene emission under high CO2 concentration, contrary to the hypothesis (Fig. 1). In fact, multiple pieces of evidence indicate that elevated CO2 actually enhances chloroplastic pyruvate levels (Rasulov et al., 2009b, 2011). Instead, the experimental evidence in this study suggests that the elevated CO2-dependent reduction in isoprene emission is due to the reduced share of photosynthetic electron flow to isoprene.