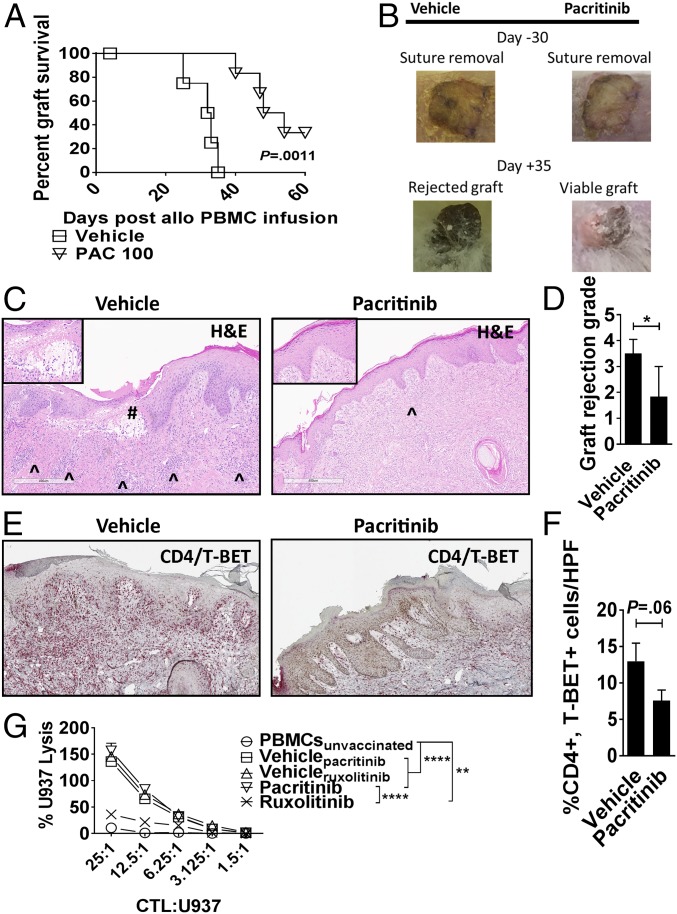

Fig. 6.

Pacritinib reduces xenograft rejection. NSG mice received a 1-cm2 split thickness human skin graft. After 30 d of rest to ensure engraftment, an inoculum of 5 × 106 human PBMCs (allogeneic to the skin) were administered by i.p. injection. Unique pairs of donor skin and allogeneic PBMCs were used for each set of experiments. Pacritinib 100 mg/kg or vehicle was given twice a day from days 0 to +14. (A) Graph shows human skin graft survival among pacritinib- or vehicle-treated NSG hosts (log-rank test). (B) Representative images show skin at time of suture removal (day −30) and at day +35. (C) Histologic representations of the skin grafts uniformly harvested on day +21 demonstrate that pacritinib reduces lymphocytic infiltration (^) and severe basal vacuolar changes of the graft, such as the subepidermal blister (#). Low power at 6×, high-power Inset at 20×. (Scale bar, 400 µm.) (D) Bar graph shows pathologic skin graft rejection scores at day +21 among vehicle- and pacritinib-treated mice. (E and F) Immunohistochemistry and accompanying bar graph shows skin-resident Th1 cells at day +21 by dual staining of CD4 (red) and T-BET (brown). n = 2 experiments, 5–6 mice per arm. (G) Graph depicts mean specific lysis ±SEM by human CD8+ CTL generated in vivo using NSG mice transplanted with human PBMCs (30 × 106) and vaccinated with irradiated U937cells (10 × 106) on days 0 and +7. Mice were treated with pacritinib (100 mg/kg twice a day), ruxolitinib (30 mg/kg twice a day), or vehicle from day 0 up to day +12. Human CD8+ T cells were harvested from euthanized mice between days +10 to +12. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments. U937 lysis was measured by colorimetric assay after 4 h. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. (Magnification: C and E, slides were scanned using a 20×/0.8 N.A. objective and viewed using a 6.5× digital zoom in ImageScope software.)