Abstract

Objective(s)

The aim of this study was to determine the association between intraoperative/pre-surgical grade of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and mortality. Additionally, we sought to determine if surgical correction of TR correlated with an increased chance of survival as compared to patients with uncorrected TR.

Methods

Grade of TR assessed by intraoperative TEE prior to surgical intervention was reviewed for 23,685 cardiac surgery patients between 1990 and 2014. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to determine association between grade of TR and the primary end-point of all-cause mortality. Association between tricuspid valve (TV) surgery and survival was determined with Cox proportional hazard regression model after matching for grade of TR.

Results

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrated a relationship between all grades of TR. Multivariable analysis of the entire cohort demonstrated significantly increased mortality for moderate (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.4; P=<.0001) and severe TR (HR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.57 to 2.6; P=<.0001). Mild TR displayed a trend for mortality (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.99–1.16, P=0.075). After matching for grade of TR and additional confounders, patients who underwent TV surgery had a statistically significant increased likelihood of survival (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.91; P=.004).

Conclusion

Our study of over 20,000 patients demonstrates that grade of TR is associated with increased risk of mortality after cardiac surgery. Additionally, all patients who underwent TV surgery, had a statistically significantly increased likelihood of survival compared to those with the same degree of TR who did not have TV surgery.

Introduction

Appreciation for the complex nature of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and its impact on long-term survival is rapidly growing. It is no longer considered a benign disease, and has garnered significant attention in regards to optimal echocardiographic assessment and timing of surgical intervention 1–3.

Current AHA/ACC guidelines give a Class I recommendation for surgical correction of severe TR in patients undergoing concurrent left-sided valve surgery4. However, uncertainty remains in relation to the appropriate management of mild and moderate TR at the time of cardiac surgery5–8. There are only Class IIa/IIb recommendations supporting surgical correction of less than severe grades of TR. This recommendation is only given in the context of left sided valve surgery and requires the presence of additional clinical and echocardiographic metrics beyond TR severity. These guidelines are reflective of the fact that limited data exists to suggest that uncorrected mild and moderate grades of TR are independent predictors of survival after cardiac surgery and that surgical correction translates into a significant survival benefit.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the association between grade of TR at the time of cardiac surgery and patient survival. Additionally, we sought to determine if surgical correction of TR correlated to an increased chance of survival as compared to patients with unrepaired TR.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

After IRB approval, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all cardiac surgical patients at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 1990 and 2014.

Data Collection

Demographic and clinical were stored in an encrypted database. Finalized intraoperative transesophageal examination (TEE) reports were obtained from an institutional database. Intraoperative pre-cardiopulmonary bypass grade of TR (mild, moderate, or severe) was assigned based on what was recorded on the finalized TEE report. Standard practice at our institution is to assign grade of TR according to the ASE guidelines for valvular regurgitation. Patients without information pertaining to the grade of TR were excluded from the study. All patients who underwent heart transplant were excluded from the study.

Endpoint

All-cause mortality was the primary endpoint. We matched operative records from our departmental TEE database with the Partners Healthcare System Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR) to obtain mortality data, which was updated from the National Death Index.

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis was performed in order to further control for potential confounding variables not available in our original database. This subgroup included all patients with additional clinical data available for query in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. Patients without additional clinical data found in the STS database were excluded from the subgroup analysis. Clinical data collected included body mass index (BMI), race, smoking history, history of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, and urgency of operation.

Statistical analysis

In the demographic tables, continuous variables and categorical variables were presented as mean ± SD and proportions, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed in R 3.1.1 (https://www.r-project.org) using the “survival” package. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using a two-sided non-parametric log-rank test. All eligible patients during the study time frame with available data were included in a univariable analysis to examine the association between potential predictors and outcome. Subsequently, a multivariable model was created which included all potential predictors. We defined the potential predictors based on a priori knowledge and decided to put all the potential predictors in the multivariable models. Mortality analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression models with follow-up as a time scale. The severe grade group did not have any outcome events after 15-years of follow-up, thus we performed the survival analyses using the 15-year follow-up data. The same statistical analysis was then repeated on the subgroup population mentioned above. To determine the association between TV surgery and mortality, we created a matching subset derived from the entire patient population, matching patients for exact tricuspid regurgitation grade, exact age category, exact left and right ventricular function, and exact year category. A Cox proportional hazard regression model with the matching variables as strata was used to determine the association between TV surgery and mortality. The proportional hazards assumption was validated by a goodness-of-test based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals We stratified by variables for which the proportional hazards assumption did not hold. The discrimination power of Cox proportional hazard regression models were evaluated by c-statistic. For all analyses, a two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 23,685 patients underwent cardiac surgery during the study period. TR was present in 32% of the population. The mean age of the patient population was 66 years with males representing 64% of the cohort. Additional baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Entire Cohort - Demographic information and baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Total cohort | TR grade=0 (n=13524) | TR grade=1 (n=4249) | TR grade=2 (n=1559) | TR grade=3 (n=620) | TR grade=missing (n=3733) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (%) | ||||||

| Age (years) Mean, SD (n=23685) | 66.4 (13.5) | 65.1 (13.7) | 68 (13.5) | 69.4 (13.6) | 66.5 (15.1) | 66.5 (15.1) |

| Male (n=23685) | 15076 (63.7%) | 8984 (66.4%) | 2434 (57.3%) | 734 (47.1%) | 253 (40.8%) | 2671 (71.6%) |

| Grade of LV Dysfunction (n=19948) | ||||||

| None (%) | 12953 (64.9%) | 9122 (67.5%) | 2392 (56.3%) | 776 (49.8%) | 342 (55.2%) | 321 (8.6%) |

| Mild (%) | 3015 (15.1%) | 1918 (14.2%) | 682 (16.1%) | 257 (16.5%) | 104 (16.8%) | 54 (1.4%) |

| Moderate (%) | 2303 (11.5%) | 1326 (9.8%) | 601 (14.1%) | 248 (15.9%) | 69 (11.1%) | 59 (1.6%) |

| Severe (%) | 1677 (8.4%) | 882 (6.5%) | 444 (10.4%) | 223 (14.3%) | 87 (14%) | 41 (1.1%) |

| Grade of RV Dysfunction (n=19837) | ||||||

| None (%) | 16839 (84.9%) | 12100 (89.5%) | 3191 (75.1%) | 962 (61.7%) | 290 (46.8%) | 296 (7.9%) |

| Mild (%) | 2011 (10.1%) | 883 (6.5%) | 658 (15.5%) | 287 (18.4%) | 143 (23.1%) | 40 (1.1%) |

| Moderate (%) | 735 (3.7%) | 197 (1.5%) | 242 (5.7%) | 175 (11.2%) | 110 (17.7%) | 11 (0.3%) |

| Severe (%) | 252 (1.3%) | 88 (0.7%) | 42 (1%) | 62 (4%) | 56 (9%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Surgical type (n=23680) | ||||||

| Tricuspid Valve (%) | 949 (4%) | 86 (0.6%) | 108 (2.5%) | 330 (21.2%) | 402 (64.8%) | 23 (0.6%) |

| Mitral Valve (%) | 5168 (21.8%) | 3030 (22.4%) | 1445 (34%) | 517 (33.2%) | 47 (7.6%) | 129 (3.5%) |

| CABG (%) | 10544 (44.5%) | 5830 (43.1%) | 1311 (30.9%) | 255 (16.4%) | 20 (3.2%) | 3128 (83.8%) |

| Aortic Valve (%) | 3940 (16.6%) | 2746 (20.3%) | 768 (18.1%) | 163 (10.5%) | 15 (2.4%) | 248 (6.6%) |

| Other (%) | 3079 (13%) | 1830 (13.5%) | 617 (14.5%) | 291 (18.7%) | 136 (21.9%) | 205 (5.5%) |

TR, tricuspid regurgitation; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle

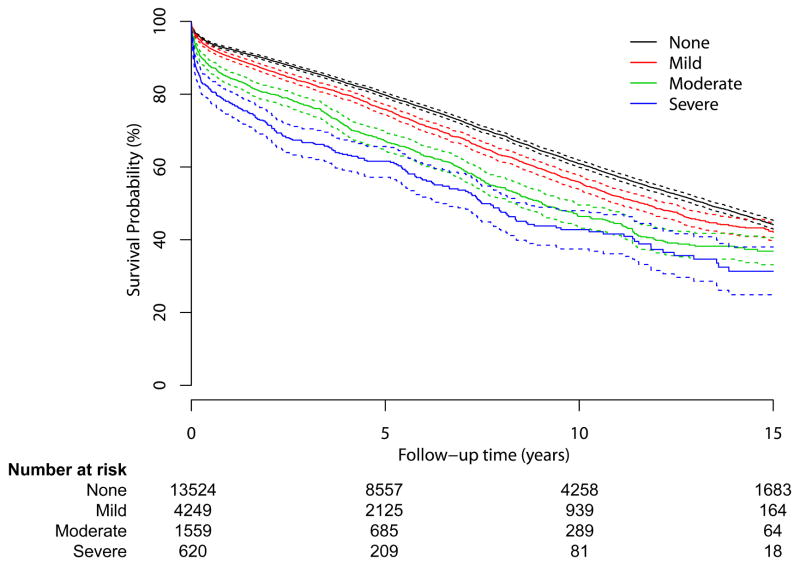

Over the 24-year study period, Kaplan-Meier survival curve demonstrated a clear relationship between the grade of TR and survival (Figure 1). Univariate analysis demonstrated a significant increase in mortality across all grades of TR severity (Mild [HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.24; P=<.0001], Moderate [HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.43 to 1.68; P=<.0001], Severe [HR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.79 to 2.28; P=<.0001]) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of grade of tricuspid regurgitation and all-cause mortality.

Table 2.

Subgroup - Demographic information and characteristics

| Characteristics | Total cohort | TR grade=0 (n=7411) | TR grade=1 (n=2930) | TR grade=2 (n=1052) | TR grade=3 (n=455) | TR grade=missing (n=2774) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (%) | ||||||

| Age (years) Mean, SD (n=14622) | 66.7 (13.1) | 65.1 (13.5) | 68.5 (13.2) | 69.7 (13.3) | 66.4 (15.1) | 66.5 (15.1) |

| BMI Mean, SD (n=14622) | 28.3 (6.1) | 28.3 (5.7) | 28 (6) | 27.4 (6.5) | 27.1 (6.4) | 27.1 (6.4) |

| Male (n=14622) | 9521 (65.1%) | 5147 (69.5%) | 1700 (58%) | 493 (46.9%) | 187 (41.1%) | 1994 (71.9%) |

| Past Medical History | ||||||

| Past smoker (n=14622) | 6799 (46.5%) | 3508 (47.3%) | 1298 (44.3%) | 436 (41.4%) | 179 (39.3%) | 1378 (49.7%) |

| Present smoker (n=14622) | 1200 (8.2%) | 695 (9.4%) | 188 (6.4%) | 52 (4.9%) | 21 (4.6%) | 244 (8.8%) |

| Diabetes (n=14622) | 3817 (26.1%) | 1860 (25.1%) | 685 (23.4%) | 233 (22.1%) | 107 (23.5%) | 932 (33.6%) |

| HLD (n=14622) | 10452 (71.5%) | 5129 (69.2%) | 2000 (68.3%) | 670 (63.7%) | 264 (58%) | 2389 (86.1%) |

| HTN (n=14622) | 10205 (69.8%) | 5039 (68%) | 2003 (68.4%) | 699 (66.4%) | 286 (62.9%) | 2178 (78.5%) |

| PVD (n=14622) | 2023 (13.8%) | 1081 (14.6%) | 377 (12.9%) | 134 (12.7%) | 47 (10.3%) | 384 (13.8%) |

| Creatinine Last (n= 14614) | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.3 (1) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| Race (n=14622) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 13704 (93.7%) | 6978 (94.2%) | 2753 (94%) | 976 (92.8%) | 419 (92.1%) | 2578 (92.9%) |

| Asian | 159 (1.1%) | 74 (1%) | 25 (0.9%) | 14 (1.3%) | 3 (0.7%) | 43 (1.6%) |

| Black | 332 (2.3%) | 149 (2%) | 73 (2.5%) | 33 (3.1%) | 18 (4%) | 59 (2.1%) |

| Hispanic | 252 (1.7%) | 116 (1.6%) | 49 (1.7%) | 20 (1.9%) | 11 (2.4%) | 56 (2%) |

| Native American | 175 (1.2%) | 94 (1.3%) | 30 (1%) | 9 (0.9%) | 4 (0.9%) | 38 (1.4%) |

| Grade of LV Dysfunction (n=11771) | ||||||

| None (%) | 7803 (66.3%) | 5044 (68.1%) | 1776 (60.6%) | 545 (51.8%) | 257 (56.5%) | 181 (6.5%) |

| Mild (%) | 1813 (15.4%) | 1072 (14.5%) | 461 (15.7%) | 173 (16.4%) | 76 (16.7%) | 31 (1.1%) |

| Moderate (%) | 1220 (10.4%) | 649 (8.8%) | 339 (11.6%) | 158 (15%) | 46 (10.1%) | 28 (1%) |

| Severe (%) | 935 (7.9%) | 446 (6%) | 270 (9.2%) | 136 (12.9%) | 65 (14.3%) | 18 (0.6%) |

| Grade of RV Dysfunction (n=11726) | ||||||

| None (%) | 9980 (85.1%) | 6614 (89.2%) | 2325 (79.4%) | 670 (63.7%) | 221 (48.6%) | 150 (5.4%) |

| Mild (%) | 1161 (9.9%) | 489 (6.6%) | 363 (12.4%) | 187 (17.8%) | 109 (24%) | 13 (0.5%) |

| Moderate (%) | 445 (3.8%) | 107 (1.4%) | 138 (4.7%) | 121 (11.5%) | 74 (16.3%) | 5 (0.2%) |

| Severe (%) | 140 (1.2%) | 41 (0.6%) | 26 (0.9%) | 33 (3.1%) | 40 (8.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Status (n=14620) | ||||||

| Elective surgery (%) | 9715 (66.4%) | 5231 (70.6%) | 1995 (68.1%) | 683 (64.9%) | 277 (60.9%) | 1529 (55.1%) |

| Emergent Surgery (%) | 264 (1.8%) | 100 (1.3%) | 64 (2.2%) | 44 (4.2%) | 16 (3.5%) | 40 (1.4%) |

| Urgent Surgery (%) | 4643 (31.8%) | 2080 (28.1%) | 871 (29.7%) | 325 (30.9%) | 162 (35.6%) | 1205 (43.4%) |

| Surgical type (n=14620) | ||||||

| Tricuspid Valve (%) | 696 (4.8%) | 30 (0.4%) | 78 (2.7%) | 254 (24.1%) | 314 (69%) | 20 (0.7%) |

| Mitral Valve (%) | 3032 (20.7%) | 1568 (21.2%) | 1006 (34.3%) | 351 (33.4%) | 32 (7%) | 75 (2.7%) |

| CABG (%) | 6663 (45.6%) | 3179 (42.9%) | 908 (31%) | 185 (17.6%) | 16 (3.5%) | 2375 (85.6%) |

| Aortic Valve (%) | 2983 (20.4%) | 1950 (26.3%) | 674 (23%) | 139 (13.2%) | 14 (3.1%) | 206 (7.4%) |

| Other (%) | 1246 (8.5%) | 683 (9.2%) | 264 (9%) | 122 (11.6%) | 79 (17.4%) | 98 (3.5%) |

BMI, body mass index; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; HLD, hyperlipidemia; HTN, hypertension; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

After adjusting for significant confounders (sex, year of operation, age, left and right ventricular function and type of surgery), the moderate and severe TR groups continued to demonstrate significantly increased risk of mortality (moderate TR [HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.1–1.4, P = <.0001]; severe TR [HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.57–2.6, P =<.0001]). The mild TR group displayed a trend for increased mortality (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.99–1.16, P=0.075) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of mortality for entire cohort: Cox proportional hazard regression univariable analyses

| Variable | Category | HR | CI (95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <30 | Ref | - | ||

| 31–40 | 1.55 | 1 – 2.4 | .051 | |

| 41–50 | 2.13 | 1.43 – 3.19 | <.0001 | |

| 41–60 | 3.15 | 2.13 – 4.65 | <.0001 | |

| 61–70 | 5.33 | 3.62 – 7.84 | <.0001 | |

| 71–80 | 9.84 | 6.69 – 14.47 | <.0001 | |

| 81–90 | 14.82 | 10.06 – 21.84 | <.0001 | |

| >91 | 19.61 | 12.63 – 30.44 | <.0001 | |

| Male Gender | 0.85 | 0.82 – 0.89 | <.0001 | |

| TR | ||||

| None | Ref | - | ||

| Mild | 1.17 | 1.1 – 1.24 | <.0001 | |

| Moderate | 1.55 | 1.43 – 1.68 | <.0001 | |

| Severe | 2.02 | 1.79 – 2.28 | <.0001 | |

| Type of Surgery | ||||

| Tricuspid valve | Ref | - | ||

| Mitral valve | 0.66 | 0.6 – 0.74 | <.0001 | |

| CABG | 0.74 | 0.67 – 0.82 | <.0001 | |

| Aortic valve | 0.50 | 0.45 – 0.56 | <.0001 | |

| Other | 0.80 | 0.72 – 0.9 | <.0001 | |

| Year of Surgery | ||||

| 2010–2014 | Ref | - | ||

| 1990–1994 | 1.85 | 1.66 – 2.07 | <.0001 | |

| 1995–1999 | 1.90 | 1.72 – 2.09 | <.0001 | |

| 2000–2004 | 1.55 | 1.4 – 1.7 | <.0001 | |

| 2005–2009 | 1.11 | 1 – 1.23 | .048 | |

| LV dysfunction | ||||

| None | Ref | - | ||

| Mild | 1.50 | 1.41 – 1.59 | <.0001 | |

| Moderate | 1.82 | 1.7 – 1.94 | <.0001 | |

| Severe | 2.05 | 1.91 – 2.21 | <.0001 | |

| RV dysfunction | ||||

| None | Ref | - | ||

| Mild | 1.53 | 1.43 – 1.64 | <.0001 | |

| Moderate | 1.70 | 1.53 – 1.89 | <.0001 | |

| Severe | 2.04 | 1.72 – 2.42 | <.0001 | |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis of patients with additional clinical data available included 11,336 patients. In the univariable analysis, all grades of TR continued to be associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality in a step-wise manner (Mild [HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.33 to 1.59; P=<.0001], Moderate [HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.78 to 2.25; P=<.0001], Severe [HR, 2.79; 95% CI, 2.37 to 3.28; P=<.0001]). Moderate and severe TR continued to demonstrate a significantly increased risk of mortality in the multivariable analysis adjusted for confounders (Moderate [HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.63; P=<.0001], Severe [HR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.61 to 3.26; P=<.0001]). The mild TR group displayed a trend for increased mortality (HR 1.11, 95% CI 1–1.1.25 P=0.06) (Table 4). The risk of mortality associated with severe TR (2.79) was greater than any other variable included in the analysis.

TABLE 4.

Grade of TR and mortality for entire cohort: Cox proportional hazard regression model multivariate analysis

| Grade of TR (n=19,157) | HR | CI (95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (%) | Ref | - | |

| Mild (%) | 1.07 | 0.99–1.16 | .076 |

| Moderate (%) | 1.24 | 1.1–1.4 | <.0001 |

| Severe (%) | 2.12 | 1.64–2.76 | <.0001 |

Model stratified by operation year, age, left and right ventricular function, and type of surgery. 7,214 death events during the follow-up. C-statistic=0.52; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

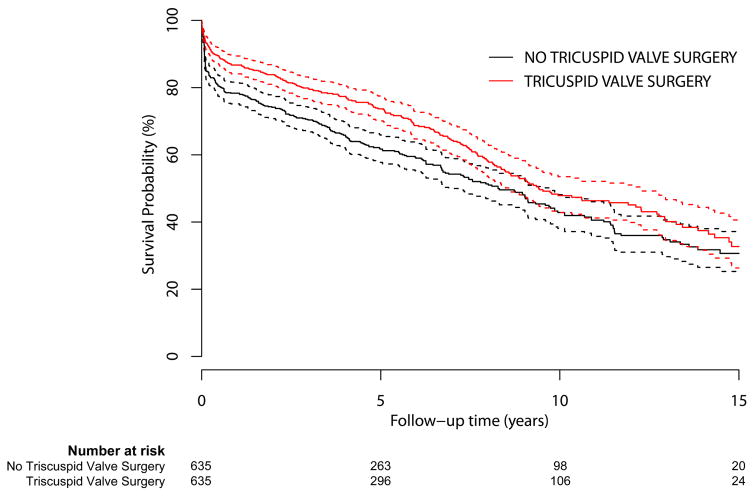

Tricuspid valve surgery

In the entire cohort of patients, TV surgery was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.24–1.53, P=<.0001). However, after matching for grade of TR and adjusting for age, LV and RV function, operation year, and sex, TV surgery was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of survival (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61–0.91, P=0.004) as compared to those who did not (Table 6). Kaplan-Meier survival curve demonstrated a robust relationship between tricuspid valve surgery and survival (Figure 2).

TABLE 6.

Type of surgery and mortality: Cox proportional hazard regression model multivariate analysis

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| No Tricuspid valve surgery (n = 635) | Ref | - |

| Tricuspid valve surgery (n = 635) | 0.74 (0.61–0.91) | .004 |

Matched (strata-method) for tricuspid regurgitation (exact match by grade), age (category), left and right ventricular function (grade), year as per above category, and sex. CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of matched patients with and without tricuspid valve surgery and all-cause mortality.

Discussion

Tricuspid regurgitation is commonly found in the general population and has a reported prevalence of up to 18.4% for grades of mild or greater9. Echocardiographic evidence of TR was present in over 30% of the 20,713 cardiac surgery patients included in our study. Understanding the prognostic implication of a risk factor as prevalent as TR, is important for counseling patients and guiding management decisions.

The significance of TR, despite its prevalence in the cardiac surgery patient population, was historically overlooked due to the theory that TR resolves after correction of left-heart pathology10. However, evidence suggests that TR often persists despite correction of left heart pathology. Even mild degrees of TR may progress to become severe in nature over time 11–17. Unfortunately, significant uncorrected TR and reoperation for TR, are both associated with increased mortality11,18–21. Consequently, several authors have suggested that in the context of left sided valve surgery, surgical correction of mild and moderate TR may be considered in order to prevent future progression.11,15,17,22,23.

The most recent AHA/ACC guidelines have now evolved to include indications for surgical intervention on the TV for less than severe grades of TR. Surgery for mild and moderate degrees of TR are only indicated, however, if the patient is already undergoing left-sided valve surgery and there is evidence of either tricuspid annular dilation, pulmonary hypertension, or right heart failure as they have may be risk factors for progression of mild and moderate TR15,17,24. If the aforementioned criteria are met, the guidelines give only a class IIa/b indication and cite a limited body of evidence (Level B/C). This has fueled continued debate, uncertainty, and further investigation.

Our retrospective study including over 20,000 patients spanning a 24-year period demonstrates that TR assessed at the time of cardiac surgery confers an increased risk of mortality. This important correlation was found to be independent of multiple known confounding variables including age, LV or RV function, and type of surgery. Most importantly, even moderate TR demonstrated a significantly increased risk of mortality. Although mild TR showed a trend for increased mortality, we did not find statistical significance.

Tricuspid annuloplasty in the setting of left-sided valve surgery may not constitute additional risk of morbidity or mortality25. However, evidence that surgical correction of less than severe TR at the time of left heart surgery significantly improves survival is limited and the results are conflicting15,26,27 In our study, prior to adjusting for confounding variables, TV surgery was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality. However, after matching for grade of TR and controlling for multiple confounding variables, patients who underwent TV surgery demonstrated a significantly increased likelihood of survival as compared to those who did not. Therefore, even patients with mild and moderate grades of TR had a significantly increased likelihood of survival if TV surgery was performed.

A particular feature of this study is its reinforcement that the TEE assessment of TR at the time of cardiac surgery is an important and relevant measure. Although there may be uncertainty about the most relevant and accurate echocardiographic metrics, this cohort suggests that intraoperative pre-surgical intervention quantification of TR severity according to ASE guidelines, is essential and has the potential to impact surgical planning and patient outcomes.

Limitations

Despite the large sample size and extensive study period, this study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Our results may support the growing body of evidence that TR is not a benign disease, but meaningful changes to clinical practice or guidelines have historically been most influenced by randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis.

It should be pointed out that we included patients undergoing a variety of cardiac surgical procedures including CABG, whereas much of the discussion regarding TR is in the context of mitral or aortic valve surgery. Additionally, we did not distinguish between TV replacement and repair.

Although we adjusted for many factors known to influence survival in cardiac surgery, the possibility for unknown confounders, or a historical bias effect despite adjusting for the year of surgery, exists. Of note, we did not consider the presence of pulmonary hypertension or tricuspid annular dilation, which are criteria for intervention in mild and moderate grades of TR. It should also be pointed out however, that echocardiographic measurement of the tricuspid annulus has inherent limitations and often differs from direct measurement by the surgeon. Additionally, TR can progress in severity despite absence of annular dilation.

We recognize that this study utilizes assessment of TR severity determined by intraoperative TEE. Surgical planning is often based on transthoracic imaging as assessment of valve regurgitation under general anesthesia may differ due to altered physiological conditions occurring under general anesthesia. Further study is warranted to compare the preoperative grade of TR assessed by TEE under general anesthesia to the pre-operative grade of TR assessed on the transthoracic echocardiogram under baseline physiological conditions and their respective relationships with operative mortality.

It is also possible that the severity of TR is actually a more sensitive surrogate for an underlying pathological condition that is the true cause of increased long term morality. Right ventricular dysfunction is one such potential etiology, causing both TR and worsened post-operative outcomes. After controlling for both left and right ventricular dysfunction, however, the observed relationship between TR and mortality remained significant.

Finally, in this study the grade of TR was based on the pre-cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) TEE rather than the post-CPB assessment at the completion of surgery and did not include follow up evaluations of TR severity. It is possible that the severity of TR was reduced postoperatively as a result of TV surgery or right ventricular remodeling. Despite this potential confounder, our comprehensive follow-up suggests that patient mortality remained significantly associated with their intraoperative, pre-CPB determined TR severity.

Conclusion

Within this large cohort of cardiac surgical patients, we have shown a robust relationship between grade of TR assessed by intraoperative TEE prior to surgical intervention and long-term mortality. This relationship remained even after controlling for known confounding variables. An important finding in our study was that even a moderate grade of TR was associated with significantly increased long-term mortality. Furthermore, our data demonstrated improved survival in patients who underwent tricuspid valve surgery for all grades of TR as compared to those who did not undergo surgical correction of TR. Going forward, randomized controlled trials are warranted to demonstrate a significant long-term survival benefit after surgical repair of less than severe grades of TR.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1. Entire Cohort: Demographic information and baseline characteristics

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 2. Subgroup - Demographics

Supplemental Table 3: Matching information

Video 1.

Video of the authors discussing the relevance of tricuspid regurgitation in the cardiac surgery patient population and the findings of this study.

TABLE 5.

Grade of TR and mortality for subgroup: Cox proportional hazard regression model multivariable analysis

| Variable | Category | HR | CI (95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade of TR (n=11,336) | ||||

| None (%) | Ref | - | ||

| Mild (%) | 1.11 | 1.0–1.25 | .060 | |

| Moderate (%) | 1.37 | 1.14–1.63 | <.0001 | |

| Severe (%) | 2.29 | 1.61–3.26 | <.0001 | |

| Male gender | 0.89 | 0.8–.98 | .019 | |

| BMI | 0.99 | .98–1.0 | .008 | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | Ref | - | ||

| Asian | 0.66 | 0.36–1.23 | .191 | |

| Black | 0.83 | 0.58–1.17 | .287 | |

| Hispanic | 0.67 | 0.45–1.0 | .051 | |

| Others | 0.8 | 0.48 to 1.32 | .381 | |

| Past smoker | 1.31 | 1.18–1.45 | <.0001 | |

| Current smoker | 1.11 | 0.92–1.33 | .263 | |

| Diabetes | 1.51 | 1.35–1.68 | <.0001 | |

| HLD | 0.91 | 0.81–1.02 | .105 | |

| HTN | 1.34 | 1.18–1.51 | <.0001 | |

| PVD | 1.46 | 1.3–1.64 | <.0001 | |

| Creatinine | 1.48 | 1.4–1.56 | <.0001 | |

| Status | ||||

| Elective (%) | Ref | - | ||

| Urgent (%) | 1.35 | 1.21–1.49 | <.0001 | |

| Emergent (%) | 1.36 | 0.99–1.87 | .057 | |

Model stratified by operation year, age, left and right ventricular function, and type of surgery. 2,636 death events during the follow-up. C-statistic = 0.64; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; BMI, body mass index; HLD, hyperlipidemia; HTN, hypertension; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Perspective.

There is limited data regarding the association between pre-operative grade of TR and mortality. Consequently, optimal management of mild and moderate TR remains controversial. We demonstrated that grade of TR is associated with increased mortality. Additionally, for patients matched by severity of TR, TV surgery was associated with increased survival.

Central Message.

Mild and moderate TR at the time of cardiac surgery increase mortality. Surgical correction of mild and moderate TR improves survival.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH R01 R01HL118266 (JDM)

Abbreviations

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASE

American Society Echocardiography

- BMI

body mass index

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

confidence interval

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HLD

hyperlipidemia

- HR

hazard ratio

- HTN

hypertension

- PVD

peripheral vascular disease

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

- TTE

transthoracic echocardiography

- TR

tricuspid regurgitation

- TV

tricuspid valve

Footnotes

IRB Protocol #: 2011P001259

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rogers JH, Bolling SF. The tricuspid valve: current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119:2718–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taramasso M, Vanermen H, Maisano F, Guidotti A, La Canna G, Alfieri O. The growing clinical importance of secondary tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:703–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers JH, Bolling SF. Valve repair for functional tricuspid valve regurgitation: anatomical and surgical considerations. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;22:84–9. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erin JP, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J American Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:e57–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raja SG, Dreyfus GD. Basis for intervention on functional tricuspid regurgitation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;22:79–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CK, Park PW, Sung K, Lee YT, Kim WS, Jun TG. Early and midterm outcomes for tricuspid valve surgery after left-sided valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ro SK, Kim JB, Jung SH, Choo SJ, Chung CH, Lee JW. Mild-to-moderate functional tricuspid regurgitation in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1092–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiran A, Sagie A. Tricuspid regurgitation in mitral valve disease incidence, prognostic implications, mechanism, and management. J Am Coll of Cardiol. 2009;53:401–08. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, Larson MG, Freed LA, Fuller DL, et al. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)01064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunwald NS, Ross J, Morrow AG. Conservative management of tricuspid regurgitation in patients undergoing mitral valve replacement. Circulation. 1967;35:63–69. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.4s1.i-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyfus GD, Corbi PJ, Chan KM, Bahrami T. Secondary tricuspid regurgitation or dilatation: which should be the criteria for surgical repair? Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duran CM. Tricuspid valve surgery revisited. J Card Surg. 1994;9:242–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1994.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuyama K, Matsumoto M, Sugita T, Nishizawa J, Tokuda Y, Matsuo T. Predictors of residual tricuspid regurgitation after mitral valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1826–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van de Veire NR, Braun J, Delgado V, Versteegh MI, Dion RA, Klautz RJ, et al. Tricuspid annuloplasty prevents right ventricular dilatation and progression of tricuspid regurgitation in patients with tricuspid annular dilatation undergoing mitral valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1431–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Sung K, Kim WS, Lee YT, Park SJ, Park PW. Clinical and hemodynamic influences of prophylactic tricuspid annuloplasty in mechanical mitral valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstone AB, Howard JL, Cohen JE, MacArthur JW, Jr, Atluri P, Woo YJ. Natural history of coexistent tricuspid regurgitation in patients with degenerative mitral valve disease: implications for future guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:2802–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Bonis M, Lapenna E, Pozzoli A, Nisi T, Giacomini A, Alfieri O. Mitral Valve Repair Without Repair of Moderate Tricuspid Regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:2206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King RM, Schaff HV, Danielson GK, Gersh BJ, Orsulak TA, Piehler JM, et al. Surgery for tricuspid regurgitation late after mitral valve replacement. Circulation. 1984;70:193–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernal JM, Morales D, Revuelta C, Llorca J, Revuelta JM, et al. Reoperations after tricuspid valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh SK, Tang GH, Maganti MD, Armstrong S, Williams WG, David TE, et al. Midterm outcomes of tricuspid valve repair versus replacement for organic tricuspid disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1735–41. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nath J, Foster E, Heidenreich PA. Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:405–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JW, Song JM, Park JP, Lee JW, Kang DH, Song JK. Long-term prognosis of isolated significant tricuspid regurgitation. Circ J. 2010;74:375–380. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chikwe J, Itagaki S, Anyanwu A, Adams DH. Impact of con-comitant tricuspid annuloplasty on tricuspid regurgitation, right ventricular function, and pulmonary artery hypertension after repair of mitral valve prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1931–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajbanshi BG, Suri RM, Nkoma VT, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Schaff HV. Influence of mitral valve repair versus replacement on the development of late functional tricuspid regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1957–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu TY, Wang JG, Meng X. Does concomitant tricuspid annuloplasty increase perioperative mortality and morbidity when correcting left-sided valve disease? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20:114–8. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navia JL, Brozzi NA, Klein AL, Ling LF, Kittayarak C, Blackstone EH, et al. Moderate tricuspid regurgitation with left-sided degenerative heart valve disease: to repair or not to repair? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Mauro M, Bivona A, Iacò AL, Contini M, Gagliardi M, Calafiore AM, et al. Mitral valve surgery for functional mitral regurgitation:prognostic role of tricuspid regurgitation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:635–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1. Entire Cohort: Demographic information and baseline characteristics

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 2. Subgroup - Demographics

Supplemental Table 3: Matching information