Abstract

Using longitudinal data from the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, this study examines the association of insurance gains and losses with prescription drug access.

Prescription drugs can effectively treat many diseases, improving quality of life, life expectancy, and population health. However, prescription drug spending has been rising rapidly in the United States resulting in concerns about affordability and patient access. Health insurance is strongly associated with prescription drug access in cross-sectional studies, but estimates may partly reflect differences between individuals with and without insurance, rather than effects of insurance coverage. To address this limitation, we used longitudinal data from the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to assess the effects of insurance gains and losses on prescription drug access.

Methods

Using longitudinal MEPS data spanning from 2008 to 2014, we categorized adults aged 18 to 64 years by insurance coverage during 2-year panels: (1) continuously insured (n = 38 231); (2) insured year 1 and lost coverage for at least 6 months in year 2 (n = 1320); (3) continuously uninsured (n = 13 516); and (4) uninsured year 1 and gained coverage for at least 6 months in year 2 (n = 1619). Unmet need for prescription drugs was measured in year 1 and year 2 based on responses to questions about delays or inability to obtain needed prescription drugs. We compared unmet need in years 1 and 2 across the 4 insurance categories and controlled for patient characteristics associated with insurance coverage and medical need (ie, age, sex, race and ethnicity, and time-varying measures of self-reported health, number of chronic conditions, and income as a percentage of federal poverty line) with a multivariable linear probability model using STATA statistical software (version 14, STATA corp). The study was covered under an institutional review board agreement designed for the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey with regard to approval and patient written informed consent.

Results

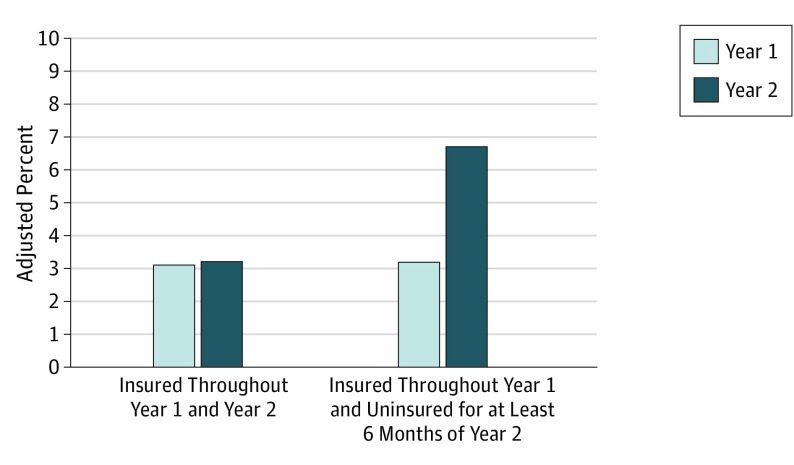

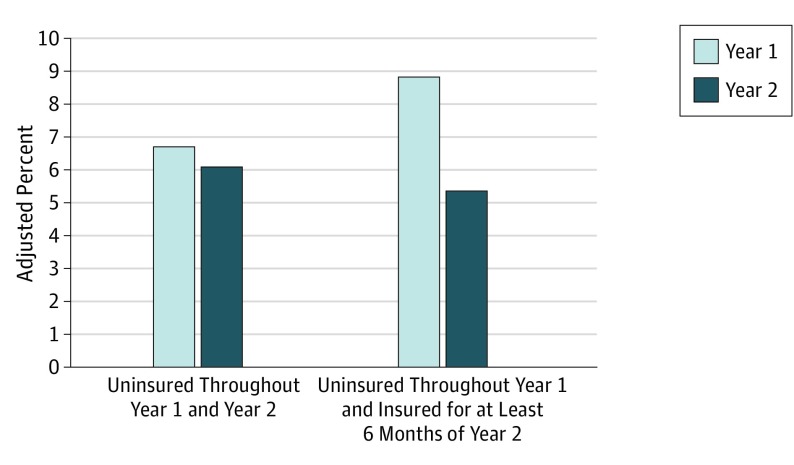

Among individuals with continuous coverage, the percent with unmet need for prescription drugs was low in years 1 and 2 (3.2% and 3.3%, respectively). In contrast, among individuals who had coverage in year 1 but lost it in year 2, the percent with unmet need more than doubled, from 3.1% to 6.6% (difference, 3.5%; 95% CI, 1.3 to 6.1; P < .05). Adjusted estimates were similar (Figure 1) and increases in unmet need for those losing insurance were significantly greater than for the continuously insured. Among individuals continuously uninsured, unmet need was similar in year 1 and year 2 (6.2% and 5.5%, respectively). However, initially uninsured individuals who gained coverage in year 2 had a 3.4 percentage point decline in unmet need (8.8% to 5.4%; 95% CI, −5.9 to −1.3; P < .05). Adjusted estimates were similar (Figure 2) and declines in unmet need for those gaining insurance were significantly greater than for the continuously uninsured. Findings were robust in sensitivity analyses of duration of insurance loss or gain and all combinations of time-varying self-reported health and individual chronic conditions.

Figure 1. Unmet Need for Prescription Drugs Among Adults Insured Throughout Year 1.

Estimates from multivariable linear probability model controlling for the effects of age, sex, and race/ethnicity in year 1 and time-varying measures of household income as a percentage of the federal poverty line, self-reported health, and number of chronic conditions (coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, other heart disease, stroke, emphysema, high cholesterol, diabetes, arthritis, and asthma). Increase in unmet need for those losing health insurance in Year 2 was significantly greater than for the continuously insured.

Figure 2. Unmet Need for Prescription Drugs Among Adults Uninsured Throughout Year 1.

Estimates from multivariable linear probability model controlling for the effects of age, sex, and race/ethnicity in year 1 and time-varying measures of household income as a percentage of the federal poverty line, self-reported health, and number chronic conditions (coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, other heart disease, stroke, emphysema, high cholesterol, diabetes, arthritis, and asthma). Decrease in unmet need for those gaining health insurance in Year 2 was significantly greater than for the continuously uninsured.

Discussion

Our findings that unmet need for prescription drugs declined among initially uninsured adults who gained coverage and doubled among initially insured adults who lost coverage provide longitudinal evidence that having and maintaining health insurance is a key protection against unmet need for prescription drugs in a nationally representative sample. However, having insurance does not guarantee coverage completeness or access to care. Patient cost sharing is increasing through higher deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance rates and medical financial hardship is increasingly documented in the United States, especially in relation to prescription drug use.

Although findings were robust in sensitivity analyses, the study was limited by self-reported measures and lack of cost-sharing information. Self-reported unmet need may not correspond exactly to objective clinical measures.

Prescription drug spending is projected to continue rising, increasing fiscal pressures on commercial, federal, state, and family budgets. For individuals with high drug costs, these trends may erode some of the protective effect of insurance coverage documented in this study. It is therefore imperative that research continue to monitor the relationship between insurance coverage and unmet need, assess spending and clinical outcomes, and that survey, administrative, and clinical data be available to do so.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Health Expenditure Data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-systems/Statistics-Trends-and-reports/NationalHealthExpendData/index.html, Accessed April 21, 2017.

- 2.Access to Healthcare in America , ed. M. Millman. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen RA, Villarroel MA. Strategies used by adults to reduce their prescription drug costs: United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(184):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure--out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1484-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]