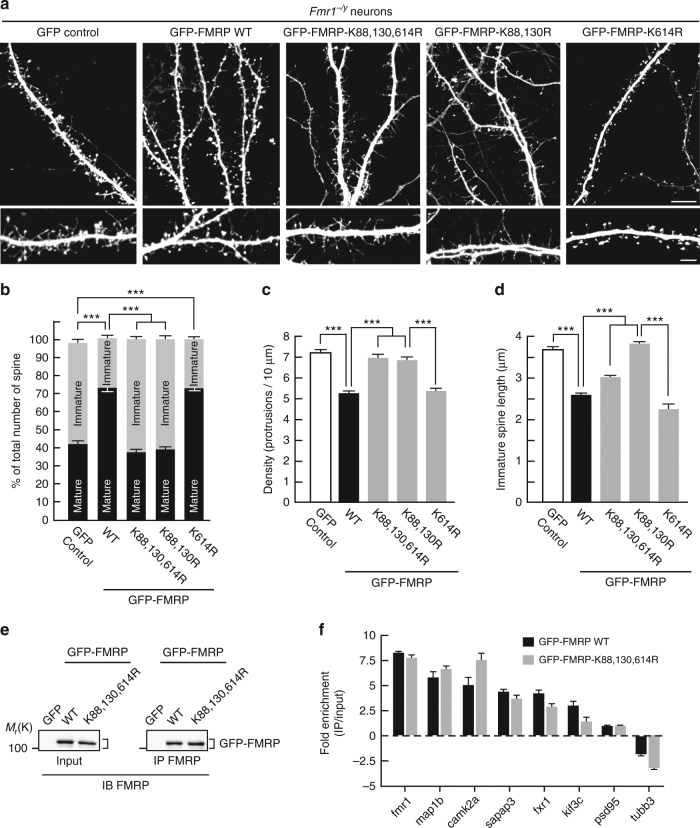

Fig. 2.

The N-terminal sumoylation of FMRP is involved in the regulation of the spine density and maturation. a Representative confocal images of dendrites from transduced Fmr1−/y neurons expressing free GFP, the WT or the non-sumoylatable K88,130,614R, K88,130R, or K614R forms of GFP-FMRP for 24 h. Bar, 10 μm. Enlargements of dendrites are also shown. Bar, 5 μm. Histograms show the relative proportion of mature and immature dendritic spines b and the density of the protrusions c in GFP, in WT, and mutated GFP-FMRP-expressing cells as shown in a. d Histograms of immature spine length measured from Fmr1−/y neurons expressing the indicated constructs. Data shown in b–d are the mean ± s.e.m. and statistical significance determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferonni post-test. N = ~4500 protrusions per condition from four independent experiments. ***p < 0.001. e, f CLIP analysis from transduced Fmr1−/y cortical neurons expressing the WT or the K88,130,614R form of GFP-FMRP revealed that they bind the same RNA repertoire. e Representative immunoblots anti-FMRP of the indicated neuronal extracts subjected or not (Input) to immunoprecipitation (IP) with FMRP antibodies. GFP-expressing Fmr1−/y neurons were used as a negative control. f Enrichment (CLIPed/Input) of a set of FMRP-target RNA fragments in the indicated conditions. Several known RNA targets of FMRP (fmr1, map1b, camk2a, sapap3, fxr1, kif3c, and psd95) as well as a non-targeted RNA (tubb3) were detected by quantitative PCR. Fold enrichment were calculated as described in the Methods section and did not show any statistical differences