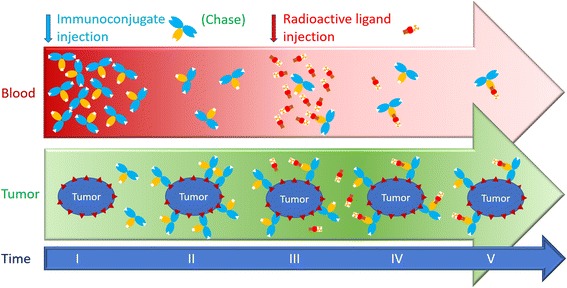

Fig. 1.

Pretargeting dosing schedule. The unlabelled immunoconjugate is injected first (I). It is allowed to distribute and bind the tumour for several hours or days (II). Then, the radioactive ligand is injected (III). It distributes rapidly and binds the tumour-associated immunoconjugate (IV). It also binds the circulating immunoconjugate that remains in the circulation. The immunoconjugate and the radiolabelled ligand must be carefully designed and the dosing schedule must be optimized to achieve the best tumour to tissue contrast ratios or the best irradiation dose ratio (V). If the amount of immunoconjugate remaining in the circulation is too high, the radiolabelled ligand is trapped in the circulation, reducing the contrast ratios and increasing the irradiation of normal tissues. If the immunoconjugate dose is insufficient, or if the radiolabelled ligand is injected too late, clearance of the immunoconjugate results in its wash-out from tumours and consequently the uptake of radioactivity in the tumour is reduced. To solve the problem, some pretargeting strategies use a clearing agent to chase the excess circulating immunoconjugate (Forero et al. 2004; Houghton et al. 2017; Knox et al. 2000; Paganelli et al. 2001). In other strategies, bivalent haptens, which bind more tightly to cell-bound than to circulating immunoconjugates, are used to carry the radionuclide (Bodet-Milin et al. 2016; Chatal et al. 2006; Gautherot et al. 2000; Kraeber-Bodéré et al. 1999; Kraeber-Bodéré et al. 2006; Kraeber-Bodéré et al. 2015; Peltier et al. 1993; Salaun et al. 2012; Schoffelen et al. 2010; Schoffelen et al. 2013; Schoffelen et al. 2014)