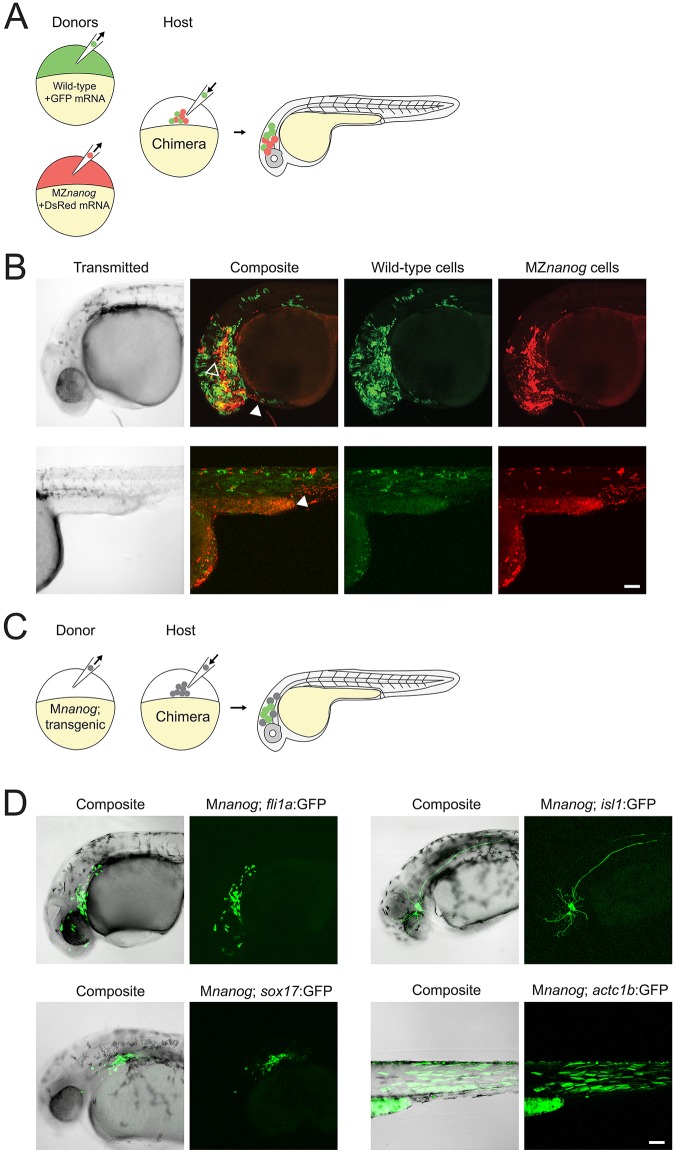

Fig. 6.

Transplantation of cells lacking Nanog into wild-type host embryos. (A) Diagram of co-transplantation of wild-type and MZnanog cells into wild-type host embryos, indicating their contribution to the host embryo. (B) Approximately 20 cells were transplanted from donor embryos (at 3-4 hpf) injected at the 1-cell stage with GFP mRNA (wild type) or DsRed mRNA (MZnanog) together into uninjected wild-type host embryos (n=27 across three independent trials). At 30 hpf, embryos were anesthetized, mounted and imaged by confocal microscopy. Two representative embryos are pictured, with arrowheads indicating contributions to eye (black arrowhead, upper row), hatching gland (white arrowhead, upper row), and muscle fibers (white arrowhead, lower row). (C) A diagram of transplantation of Mnanog; transgenic cells into a wild-type host embryo, with green cells in the host embryo indicating activation of the transgene in transplanted cells. Donor embryos (‘Mnanog; transgenic’) were the progeny of a Znanog female crossed to a transgenic male. (D) Approximately 20 cells were transplanted from donor embryos into uninjected wild-type host embryos. At 30 hpf, embryos were anesthetized, mounted and imaged by confocal microscopy. Representative embryos in all panels are displayed as maximum projections from a subset of a z-stack, with transgene or tracer expression overlaid onto the other channel or transmitted light channel for context (‘Composite’). Transgenic lines used were Tg(fli1a:GFP)y1 (n=11; Lawson and Weinstein, 2002), Tg(sox17:GFP)s870 (n=4, Sakaguchi et al., 2006), Tg(isl1:Gal4-VP16;UAS:GFP)zf154 (abbreviated isl1:GFP) (n=16; Sagasti et al., 2005) and Tg(actc1b:GFP)zf13 (n=5; Higashijima et al., 1997). Wild-type expression patterns for each transgene are shown in Fig. S4 for comparison. Scale bars: 100 μm.