Abstract

High-intensity focused ultrasonography is the only completely non-invasive thermal therapy. To date its applications have been limited but clinical indications are expanding with enhanced technological advances that have increased the accuracy of targeting and decreased the duration of treatment times. We report its first use for rectal cancer.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Rectal cancer, Transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound

Locally recurrent rectal cancer can give rise to unpleasant symptoms such as tenesmus, mucus discharge and bleeding. Symptom progression usually results in deterioration of quality of life, especially following failure of conventional treatment options such as radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy. There is a clear and unmet need for new therapeutic options in this situation.

High-intensity focused ultrasonography (HIFU) is a novel non-invasive ablative technology. By delivering high-power ultrasound waves to a small focal area, temperatures above 60°C (usually 80–90°C) can be reached. This results in coagulative necrosis and cavitation.1 HIFU transducers produce sequential, adjacent cigar shaped zones of ablation that are very versatile and able to treat any size or shape of tissue that lies at the focal length of the ultrasound beam.

Although HIFU has been attempted for the treatment of both benign and malignant disease over many decades, its use has previously been limited by technological imperfections such as the accuracy of targeting and long treatment times.1 Recent improvements in HIFU technology and wider experience in applications of HIFU techniques have led to increasing recognition of its potential and a rise in numbers of treatments and clinical indications.1

HIFU can be delivered by either an intracavitary or an extracorporeal device, using B-mode ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for real-time feedback.1 HIFU is most commonly used to treat prostate cancer1,2 (intracavitary/transrectal) and uterine fibroids1,3 (extracorporeal) in which the ability to ablate abnormal tissue precisely, avoiding normal surrounding tissue, is important. Treatment in other cancers, including liver and pancreas, is being explored.1

HIFU may be used either alone or in combination as multimodal therapy and can also be used repeatedly as there appears to be no limiting cumulative effect.

We have initiated a clinical trial (number 09/H0808/43) approved by the UK national ethics committee to investigate the feasibility, toxicity and tumour response of HIFU in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. We report the first use of HIFU to treat rectal cancer.

Patient and treatment details

A 78-year-old male patient had an open anterior resection for a pT4 N2 M0 adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon with restoration of bowel continuity. Histology revealed a tumour within 1mm of the posterior circumferential resection margin and 19 of 47 lymph nodes were positive. The patient was considered too frail to undergo post-surgical adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy at that time.

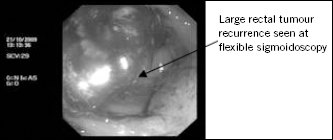

Five months after surgery, the patient developed tenesmus and frequent bowel motions (every 30 minutes) mixed with blood and mucus. A flexible sigmoidoscopy demonstrated a hemicircumferential rectal anastomotic recurrence on the posterior wall, 6cm from the anal verge (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

MRI and computed tomography showed circumferential thickening of the distal sigmoid and rectum most marked on the right, measuring 3cm with associated local lymph node enlargement and a large liver metastasis (9.0cm x 7.2cm).

HIFU treatment

Following written informed consent, a transrectal HIFU device (Sonablate® 500, Focus Surgery Inc, Indianapolis, IN, US) was passed easily into the rectum under general anaesthetic. The tumour was imaged in real time using the built-in diagnostic ultrasound probe in order to plan and monitor treatment. The total tumour volume was estimated at 30cm3. For safety, the proposed treatment volume was defined to include one-third of the tumour volume only. In addition, only the exophytic and superficial parts of the recurrence were targeted in order to minimise the risk of perforation or fistula formation.

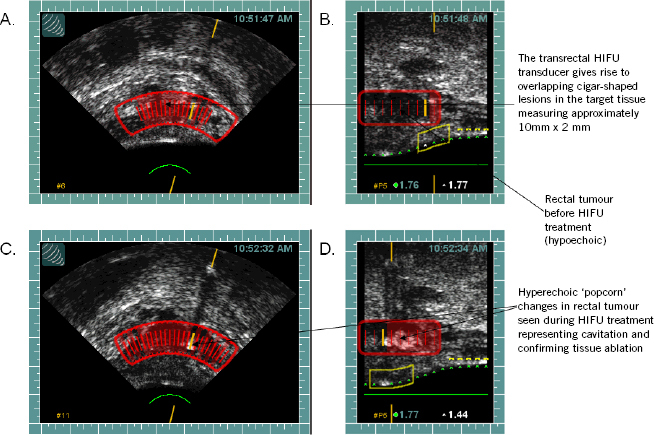

HIFU treatment of prostate cancer typically uses 35–40W/ cm2 per pulse with acoustic intensity at the focal area of approximately 1,500W/cm2. Our protocol started at 20W/cm2 per pulse. Real-time tissue changes in the form of hyperechoic greyscale changes on ultrasonography (Fig 2) provide feedback during HIFU that temperatures of sufficient magnitude have been reached to achieve tissue ablation. These were observed throughout the 29 minutes of treatment.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative transrectal diagnostic ultrasonography from HIFU device demonstrating the rectal tumour before treatment and hyperechoic changes after treatment in the sector targeted, confirming cavitation and tissue ablation. The Sonablate® 500 HIFU device is able to generate diagnostic ultrasonography and therapeutic HIFU simultaneously from the same transducer.

(A) Transverse and (B) sagittal intraoperative transrectal diagnostic ultrasonography and treatment planning template from the HIFU device, demonstrating the rectal tumour before treatment; (C) transverse and (D) sagittal intraoperative transrectal diagnostic ultrasonography from the HIFU device, demonstrating the rectal tumour after treatment with hyperechoic changes confirming cavitation and tissue ablation.

Post-treatment outcomes

There were no procedural related adverse events and no adverse events were reported by day 30. The patient reported immediate improvements in stool frequency, which within 24 hours had decreased from every 30 minutes to 3–4 times daily with little mucous and no bleeding, maintained to day 30.

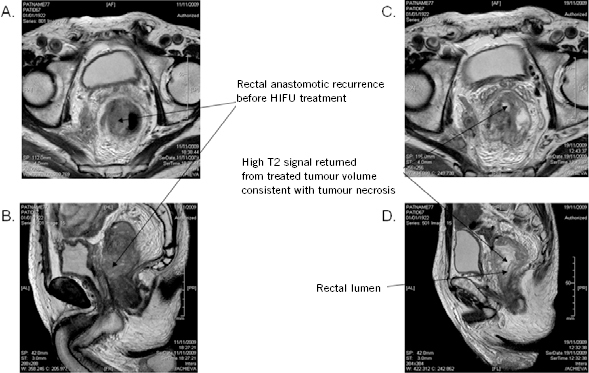

Repeat MRI was performed at 7 days post treatment and showed tumour necrosis as defined by a high signal on the T2 weighted images. This area corresponded to the area targeted by HIFU (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Pre and post-HIFU treatment pelvic MRI one day before HIFU treatment and one week after HIFU treatment showing areas of necrosis within the target volume. (A) 1 day pre-HIFU treatment T2W MRI PELvIS (axial); (B) 1 day pre-HIFU treatment T2W MRI PELvIS (sagittal); (C) 7 days post-HIFU treatment T2W MRI PELvIS (transverse); (D) days post-HIFU treatment T2W MRI PELvIS (sagittal) (T2W = T2 weighted)

Although unlimited re-treatments with HIFU are possible, this was not permitted in our current phase I/II study. The patient’s general clinical condition had improved sufficiently by day 30 to be treated with palliative radiotherapy to the rectum (30Gy in 10 fractions) with no recorded increase in additive acute or late toxicity by 5 months. He had been previously judged clinically unfit for this. HIFU does not appear to compromise subsequent radiotherapy.

Conclusions

This is the first report of HIFU in treating locally recurrent rectal cancer and has demonstrated that treatment is feasible, well tolerated, rapid and relieves local symptoms. Even at the relatively low intensity used in this study of 20W/cm2, HIFU produced tumour necrosis in the treatment volume targeted and improved symptoms. The optimal role of HIFU in the treatment of recurrent rectal cancer is currently being determined, as is the potential to offer unlimited re-treatment, an attribute lacking with other therapeutic modalities. This first attempt at rectal HIFU suggests a possible role in the palliative treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer and warrants further study. Modifications to the current transrectal HIFU device for this new application are now required to expand its application for rectal cancers.

Acknowledgements

We thank UKHIFU Ltd for supplying a Sonablate® 500 HIFU device and we are grateful for the funding of £45,000 from the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust National Institute for Health Research comprehensive biomedical research centre.

Conflicts of interest

P Abel and J Hand are party to a proposed university spinout for an extracorporeal device.

References

- 1.Kennedy JE. High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed HU, Zacharakis E, Dudderidge T et al. . High-intensity-focused ultrasound in the treatment of primary prostate cancer: the first UK series. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart EA, Gedroyc WM, Tempany CM et al. . Focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroid tumors: safety and feasibility of a noninvasive thermoablative technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]