Abstract

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) as a treatment in severe aortic stenosis (AS) is an excellent alternative to conventional surgical replacement. However, long-term outcomes are not benign. Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade has shown benefit in terms of adverse remodelling in severe AS and after surgical replacement.

Methods and analysis

The RAS blockade after TAVI (RASTAVI) trial aims to detect if there is a benefit in clinical outcomes and ventricular remodelling with this therapeutic strategy following the TAVI procedure. The study has been designed as a randomised 1:1 open-label study that will be undertaken in 8 centres including 336 TAVI recipients. All patients will receive the standard treatment. The active treatment group will receive ramipril as well. Randomisation will be done before discharge, after signing informed consent. All patients will be followed up for 3 years. A cardiac magnetic resonance will be performed initially and at 1 year to assess ventricular remodelling, defined as ventricular dimensions, ejection fraction, ventricular mass and fibrosis. Recorded events will include cardiac death, admission due to heart failure and stroke. The RASTAVI Study will improve the management of patients after TAVI and may help to increase their quality of life, reduce readmissions and improve long-term survival in this scenario.

Ethics and dissemination

All authors and local ethics committees have approved the study design. All patients will provide informed consent. Results will be published irrespective of whether the findings are positive or negative.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult cardiology, echocardiography, heart failure, valvular heart disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Ventricular remodelling following tanscatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has not been studied much, to date. This is the first study to prospectively explore the impact of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) modulation in this scenario; in addition, the consequences of RAS blockade in major outcomes of patients harbouring a TAVI device will also be explored.

The design as a randomised 1:1 open label study (ramipril vs standard care) and the vast experience of the participating institutions will confer great validity to future findings.

Also, the central analysis of cardiac magnetic resonance examinations will increase the accuracy of measurements and, therefore, validity.

As a limitation, bias could be derived from the unblinded nature of the study for the treating specialist; external monitoring will be performed to control this risk.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the result of a slow progressive disease related to atherosclerosis, inflammation, haemodynamic factors and active calcification.1 It presents an age-related growing incidence as a result of these degenerative mechanisms and, therefore, it has a great impact in the ageing population of developed countries.2 In parallel, old patients often present an increased risk for conventional surgery due to frailty and comorbidities. For this reason, in the last decade the use of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) as a less invasive alternative to treat AS has increased exponentially.3–5

Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of TAVI in high-risk and intermediate-risk patients,3–7 but clinical practice has rapidly moved forward in this scenario, often beyond current evidence and despite a number of unanswered questions remaining, that include the identification of factors with potential impact in long-term outcomes.8 In particular, the presence of fibrosis and myocardial hypertrophy in patients with AS has been related to worse prognosis especially if they persist once the valvular obstruction has been treated.9–13 Therefore, better outcomes may be achieved with the use of strategies improving cardiac remodelling by reversing fibrosis and hypertrophy.14–16 In this regard, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade has been shown to have a positive impact in remodelling and in major clinical outcomes in alternative scenarios.17–24 In particular, its use in patients with AS and in those undergoing conventional surgery, has demonstrated consistent benefit.25–28 However, there are no data regarding the effects of this therapy for TAVI recipients.

The RAS blockade after TAVI (RASTAVI) Study (http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03201185) aims to investigate the effect of adding ramipril to the standard care in patients successfully treated with TAVI in terms of ventricular remodelling as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and in the main clinical outcomes.

Methods and analysis

The RASTAVI Study is a national, multicentre, open-label and randomised 1:1 trial aiming to determine the effect of ramipril on cardiac events, functional capacity and the evolution of cardiac remodelling on patients with AS undergoing TAVI. Online supplementary files 1–3 show the official version of the protocol, the financial sources and the model consent form, respectively.

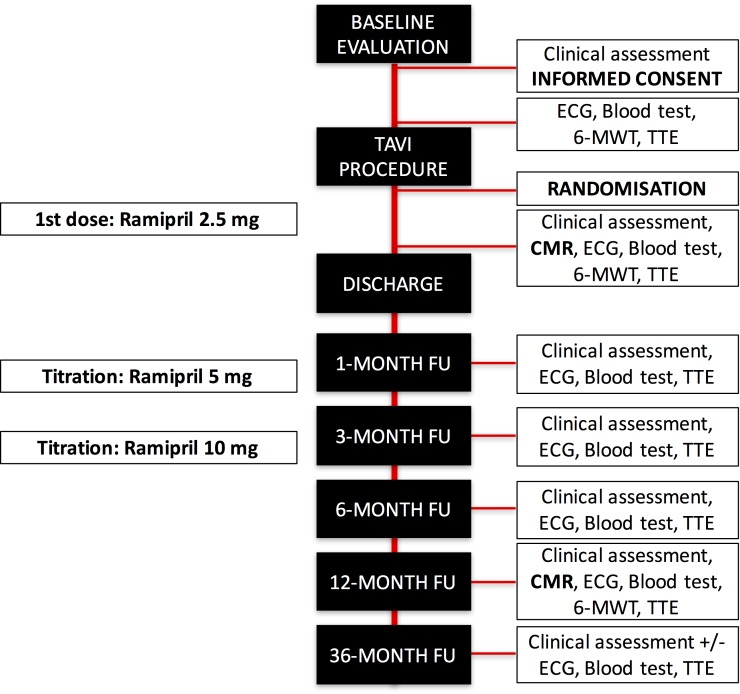

Patients across eight centres (summarised in table 1) will be randomised to receive conventional treatment or conventional treatment plus ramipril. Regular pathways exist to communicate important protocol modifications if any. Workflow has been schematically depicted in figure 1. Briefly, after initial clinical evaluation to determine the suitability of the candidate, informed consent will be obtained by the investigators and standard baseline evaluation including transthoracic echocardiography, blood tests and 6-minutes walk test will be performed. After the TAVI procedure the patients will be randomised to receive either standard care or an initial dose of ramipril (2.5 mg). Titration of the ramipril dose will be performed at 1-month and 3 month follow-up visits aiming 10 mg daily if tolerated; in case there are symptoms related to dose increase, it will be reduced to the previous dose. Patients in the control group will not receive RAS inhibitors throughout the study; if their blood pressure is beyond recommended parameters (140/90 mm Hg) the physician responsible for the patient will administer any medication to control it except for RAS blockers.

Table 1.

RASTAVI Study expected recruitment

| Centre | City | Country | Expected number of patients recruited (2 years) |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (coordinating centre) |

Valladolid | Spain | 50 |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | Madrid | Spain | 50 |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro | Madrid | Spain | 35 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | Málaga | Spain | 50 |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos | Madrid | Spain | 50 |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | Barcelona | Spain | 35 |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron | Barcelona | Spain | 35 |

| Hospital Universitario de Vigo | Vigo | Spain | 35 |

RASTAVI, renin-angiotensin system blockade after transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Figure 1.

Schematic workflow for the RAS blockade after TAVI (RASTAVI) Study. 6-MWT: 6-min walk test; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; FU, follow-up; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography. Note: telephonic 36-month follow-up visit is allowed.

A baseline CMR will be performed and repeated at 1-year follow-up. Central analysis of all images will be performed by an independent unit (www.icicorelab.es). Main parameters to be recorded are summarised in box 1. The steering committee in the coordinating centre will determine adjudication of the responsibilities and events according to the criteria defined in the study protocol.

Box 1. Main clinical and imaging parameters that will be recorded for each patient.

1) Clinical evaluation

Age, gender, height, weight, body mass index, body surface, cardiovascular risk factors, medications, familial and personal background, date of first diagnosis of aortic stenosis, former ischaemic cardiomyopathy, former cerebrovascular events, peripheral arterial disease, pulmonary disease, main symptoms (including NYHA class), arterial pressure, heart rate, murmurs, heart failure signs, quality of life questionnaire, frailty evaluation.

ECG: sinus rhythm, atrial fibrillation, pacemaker, atrial or ventricular hypertrophy.

Blood tests: haemoglobin, haematocrit, lipids, NT-proBNP, T-Tn, electrolytes, C reactive protein, creatinine, glomerular filtration rate.

2) Transthoracic echocardiography (height, weight, arterial pressure and heart rate will be recorded)

Left atrium: telediastolic diameters; telesystolic diameters.

Basal interventricular septum and posterior wall width; LV mass.

LV telediastolic and telesystolic volume, stroke volume, ejection fraction (Teicholz and Simpson).

Aortic valve: peak velocity, peak and mean gradient and VTI for LVOT and aortic valve; LVOT diameter, estimated aortic valve area, presence and severity of aortic regurgitation (I/II/III), location of regurgitation (periprosthetic or intraprosthetic).

Mitral valve: normal; degenerative; rheumatic; severity of regurgitation (I/II/III); mechanism of regurgitation (functional due to annular dilation/functional due to tenting/rheumatic/ degenerative); ERO.

Tricuspid valve: TAPSE; lateral S wave; regurgitation; severity of regurgitation (I/II/III); systolic peak gradient between right ventricle and right atrium; dimensions of inferior vena cava and respiratory variations (no/less than 50% or more than 50%).

Diastolic function parameters: E and A waves; E/A; deceleration time of E wave; isovolumetric relaxation time; E' wave; A' wave.

3) Cardiac magnetic resonance (all exams will be performed with 1.5 Tesla systems, synchronised and during respiratory apnoea; height, weight, arterial pressure and heart rate will be recorded)

Locators of three planes in the space (axial, coronal and sagittal) enclosing the entire cardiac area.

Right and left ventricular function study: SSFP sequences (TrueFISP, bTFE, FIESTA): a) four-chamber view (horizontal long-axis), two-chamber view (vertical long-axis) and complete short-axis; b) 30 phases, 8 mm width, 0 mm gap.

Quantification of residual aortic regurgitation through contrast phase sequences.

Delayed enhancement inversion recovery sequences after administration of 0.2 mmol/kg of gadolinium: a) Beginning 10 min after gadolinium administration; b) four-chamber, two-chamber and short axis views acquisition; c) Analysis of the following parameters: Telediastolic left ventricular volume (mL/m2); telesystolic left ventricular volume (mL/m2); stroke volume (mL); left ventricular ejection fraction (%); cardiac mass (g/m2); segmentary wall width (mm); telediastolic right ventricular volume (mL/m2); telesystolic right ventricular volume (mL/m2); right ventricular stroke volume (ml); right ventricular ejection fraction (%); myocardial deformation parameters: strain, strain rate, shift, speed, torsion and torsion rate; longitudinal strain, radial strain and circumferencial strain; quantification of residual aortic regurgitation (regurgitant volume ml; regurgitant fraction, %); presence and degree of myocardial fibrosis: location (subendocardial, subepicardial, intramyocardial), total fibrotic mass (total grams and % of total left ventricular mass).

bTFE, balanced turbo field echo; ERO, effective orifice area; FIESTA, Fast imaging employing steady state; LV, left ventricle; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NT-proBNP, N-termina pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SSFP, steady-state free precession; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; T-Tn, T-Troponin; TrueFISP, True fast imaging with steady state precession; VTI, velocity-time integral.

Inclusion criteria

The target population will include patients over 60 years of age with severe AS assessed by transthoracic echocardiography who successfully undergo TAVI following approval by the heart team. Patients must be capable of understanding, accepting and signing informed consent. Successful TAVI procedure will follow the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 definition of ‘device success’.29

Exclusion criteria

Patients presenting with any of the following conditions will be excluded from the study: mitral disease requiring intervention, ventricular ejection fraction below 40%, prior myocardial infarction or dilated cardiomyopathy, presence of magnetic resonance incompatibilities (ie, devices, morbid obesity or claustrophobia), use of drugs for RAS blockade within the last 3 months or intolerance, allergy or contraindication for their use, including glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min and persistent hypotension (defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure <100 or <60 mm Hg, respectively.)

Objectives

The primary aim is to analyse the impact of ramipril associated with conventional treatment following percutaneous aortic valve replacement in terms of reduction of cardiac mortality, heart failure admissions and cerebrovascular events at 3-year follow-up.

Secondary objectives include left ventricular remodelling determined by ventricular mass, fibrosis and ejection fraction as assessed by CMR. Also, functional capacity after 1 year will be analysed.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation was based on former studies in patients with AS.22–24 First, the study by Dahl et al27 included 114 patients and evaluated left ventricular mass after 1 year under treatment or standard care with a significant greater reduction of mass in the active group. Analysis of these data suggests the need for at least 79 patients in each group. Second, the research by Goel et al26 retrospectively included 1752 patients aiming to analyse the impact on mortality; a propensity score subanalysis including 594 patients reported a 5-year mortality rate of 10% in the active group and 22% in the control group. From these data we estimated that two groups with 150 patients each were necessary. In addition, in the Heart Outcome Prevention Evaluation Study,30 ramipril was stopped in 7% of the patients due to persistent cough. Taking this into consideration and after fixing α and β errors of 0.05 and 0.20, respectively, we estimate a sample size of 336 patients for the RASTAVI Study (including 5% potential missing subjects).

We will use the C4-Study design pack (Glaxo Welcome, V.1.1) as an independent system for blocked randomisation with balance across groups and blocks of four and six patients that will be randomly selected.

Finally, statistical analysis for categorical variables will be expressed both as absolute values and percentages and for continuous variables as average and SD, median and IQR. Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test will be performed for comparisons between groups with qualitative variables, and Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. All P values will be bilateral and will be considered statistically significant when <0.05. Statistical package SSPS V.23 will be used.

Analysis

There is a growing use of TAVI in younger patients and it is expected to become the standard care for AS in the coming years. However, outcomes following TAVI are not benign at all. In this regard, consensus exists regarding the need for measures and therapies that improve the long-term results following percutaneous aortic valve replacement.

The development of left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis results in poor outcome in patients with AS9 10 and the persistence of hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction after surgical valve replacement increases mortality.23 24 Likewise, we can assume a similar role of adverse remodelling following TAVI. Moreover, the common presence of other concomitant cardiovascular diseases such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension increases the risk for developing heart failure, reducing the quality of life and survival after TAVI, even in patients without previous myocardial infarction and with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. For this reason, the first-year readmission rate for any reason (44%), and specifically due to heart failure (12%), still remains high.31

A putative beneficial effect of RAS blockade after aortic valve replacement has been explored in several studies. A retrospective work in 150 patients showed that RAS blockade reduced hospital admission and deaths.25 Of note, this effect was independent of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes, suggesting a benefit of RAS blockade in patients with normal ventricular function and dimensions. A propensity analysis in 1752 patients suggested a better outcome when RAS was pharmacologically blocked.26 Both studies have important limitations, including their retrospective nature, the lenient inclusion criteria and the lack of information regarding type and dose of drugs given to the patients. Although some authors had suggested a drug class effect of RAS inhibitors, it is generally accepted that there is no such effect given the differences in lipophilia, half life, effect duration and other pharmacological properties. Ramipril presents a favourable clinical profile and excellent results in prior clinical trials. Yusuf et al demonstrated that ramipril could prevent adverse ventricular remodelling and reduce adverse events including death, myocardial infarction and stroke in patients with high cardiovascular risk and no ventricular dysfunction or heart failure.30

There is only one prospective study in the surgical setting, with 114 patients, in which candesartan (32 mg per day) was compared with a control group.27 One year after valve replacement, a reduction in left ventricular mass was more pronounced in the active group. Also, one single study has analysed retrospectively the effects of RAS blockade in patients harbouring a TAVI device suggesting that this therapy could be associated with greater left ventricular mass index regression and reduced all-cause mortality.32 However, any randomised trial has confirmed this hypothesis. The RASTAVI Study is the first formal attempt to clarify the role of RAS inhibitors in the prognosis of these patients.

Limitations include a potential risk of high unexpected cross-over that might force to increase the number of participating institutions. Also, the unblinded nature of the study for the treating specialist can represent a potential bias that will be addressed by external monitoring of all clinical records and independent central analysis of all imaging parameters by experts in cardiac imaging, unaware of the assignment of the patients.

In conclusion, patients with AS treated with TAVI are at risk for developing persistent left ventricular adverse remodelling, heart failure and, consequently, early mortality. The results of the RASTAVI Study will contribute to improve the management of patients after TAVI and, if the results are positive for the active group, may potentially increase the quality of life, reduce rehospitalisations and improve the long-term survival in this scenario.

Clinical events will be recorded and will be adjudicated by a scientific committee including a clinical cardiologist, an interventional cardiologist and a neurologist who will be blinded to the therapeutic group to which the patient belongs. External independent monitoring of the study will be performed. Anonymised samples and imaging tests will be stored with restricted access to the investigators of the study. Liability insurance will be provided for compensation to those who may potentially suffer harm from trial participation. Only the principal investigator of each participating institution will have access to the final trial data set.

bmjopen-2017-020255supp001.pdf (478.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020255supp002.jpg (1.3MB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-020255supp003.pdf (36.9KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Hypothesis and study design: IJA-S, PC, JL, LHV-F, TS, RA, AR, JASR. Approval of the protocol and commitment to recruitment during the study duration: IJA-S, FDdH, JAF-D, JHA-B, MDT, AR, PJ-S, VS, EG-I, AJM-G, LN-F, MS, VAJ-D, BGdB, JASR. Imaging and clinical evaluation during the study duration: IJA-S, PC, FDdH, JAF-D, JHA-B, MDT, AR, PJ-S, VS, EG-I, AJM-G, LN-F, MS, VAJ-D, BGdB, JL, LHV-F, TS, RA, MDT, AR, JASR. Final approval of the manuscript of the study design: all authors.

Funding: Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad), grant number PI17/02237.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Insituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministry of Health). Local ethics committees have provided informed consent adhering to the directions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the legal dispositions 14/2007 and RD 1090/2015 regarding biomedical research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkilä J, et al. . Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:1220–5. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90249-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridgewater B, Gummert J. Fourth ECATS Adult Cardiac Surgical Database Report: towards global benchmarking. Dendrite Clinical Systems ISBN. 1-903968-26-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. . Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1597–607. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. . Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2187–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al. . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1790–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa1400590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. . Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1609–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reardon MJ, Adams DH, Kleiman NS, et al. . 2-Year outcomes in patients undergoing surgical or self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:113–21. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Trigo M, Muñoz-Garcia AJ, Wijeysundera HC, et al. . Incidence, timing, and predictors of valve hemodynamic deterioration after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:644–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cioffi G, Faggiano P, Vizzardi E, et al. . Prognostic effect of inappropriately high left ventricular mass in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Heart 2011;97:301–7. 10.1136/hrt.2010.192997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, et al. . Midwall fibrosis is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1271–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schunkert H, Jackson B, Tang SS, et al. . Distribution and functional significance of cardiac angiotensin converting enzyme in hypertrophied rat hearts. Circulation 1993;87:1328–39. 10.1161/01.CIR.87.4.1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fielitz J, Hein S, Mitrovic V, et al. . Activation of the cardiac renin-angiotensin system and increased myocardial collagen expression in human aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1443–9. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01170-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujisaka T, Hoshiga M, Hotchi J, et al. . Angiotensin II promotes aortic valve thickening independent of elevated blood pressure in apolipoprotein-E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2013;226:82–7. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwin SE, Katz SE, Weinberg EO, et al. . Serial echocardiographic-Doppler assessment of left ventricular geometry and function in rats with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition attenuates the transition to heart failure. Circulation 1995;91:2642–54. 10.1161/01.CIR.91.10.2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlöf B, Pennert K, Hansson L. Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients. A metaanalysis of 109 treatment studies. Am J Hypertens 1992;5:95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Díez J, Querejeta R, López B, et al. . Losartan-dependent regression of myocardial fibrosis is associated with reduction of left ventricular chamber stiffness in hypertensive patients. Circulation 2002;105:2512–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000017264.66561.3D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedberg K; CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987;316:1429–35. 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg B, Quinones MA, Koilpillai C, et al. . Effects of long-term enalapril therapy on cardiac structure and function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Results of the SOLVD echocardiography substudy. Circulation 1995;91:2573–81. 10.1161/01.CIR.91.10.2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalsgaard M, Iversen K, Kjaergaard J, et al. . Short-term hemodynamic effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with severe aortic stenosis: a placebo-controlled, randomized study. Am Heart J 2014;167:226–34. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bull S, Loudon M, Francis JM, et al. . A prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor Ramipril In Aortic Stenosis (RIAS trial). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:834–41. 10.1093/ehjci/jev043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bang CN, Greve AM, Køber L, et al. . Renin-angiotensin system inhibition is not associated with increased sudden cardiac death, cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol 2014;175:492–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadir MA, Wei L, Elder DH, et al. . Impact of renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy on outcome in aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:570–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund O, Erlandsen M, Dørup I, et al. . Predictable changes in left ventricular mass and function during ten years after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis 2004;13:357–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gjertsson P, Caidahl K, Farasati M, et al. . Preoperative moderate to severe diastolic dysfunction: a novel Doppler echocardiographic long-term prognostic factor in patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:890–6. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yiu KH, Ng WS, Chan D, et al. . Improved prognosis following renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in patients undergoing concomitant aortic and mitral valve replacement. Int J Cardiol 2014;177:680–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goel SS, Aksoy O, Gupta S, et al. . Renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy after surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:699–710. 10.7326/M13-1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahl JS, Videbaek L, Poulsen MK, et al. . Effect of candesartan treatment on left ventricular remodeling after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:713–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. . Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med;200:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, et al. . Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the valve academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2403–18. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold JM, Yusuf S, Young J, et al. . Prevention of heart failure in patients in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study. Circulation 2003;107:1284–90. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000054165.93055.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nombela-Franco L, del Trigo M, Morrison-Polo G, et al. . Incidence, causes, and predictors of early (≤30 days) and late unplanned hospital readmissions after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:1748–57. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochiai T, Saito S, Yamanaka F, et al. . Renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart 2017. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311738 [Epub ahead of print 6 Oct 2017]. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020255supp001.pdf (478.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020255supp002.jpg (1.3MB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-020255supp003.pdf (36.9KB, pdf)