Abstract

A considerable number of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients are infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is correlated with their poor outcomes. However, the role of HBV infection in DLBCL treatment failure remains poorly understood. Here, our data demonstrated that HBV infection was closely associated with poorer clinical prognosis independent of its hepatic dysfunction in germinal center B-cell type (GCB type) DLBCL patients. Interestingly, we found that DLBCL cells expressing hepatitis B virus X protein (HBX) did not exhibit enhanced cell growth but did show reduced sensitivity to methotrexate (MTX) and cytarabine (Ara-C), which induced S-phase arrest. Mechanism studies showed that HBX specifically inhibited the phosphorylation of checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2, a key DNA damage response protein). CHK2 depletion similarly conferred resistance to the S-phase arrest-inducing chemotherapeutics, consistent with HBX overexpression in DLBCL cells. Moreover, overexpression of wild-type CHK2 rather than its unphosphorylated mutant (T68A) significantly restored the reduced chemosensitivity in HBX-expressing cells, suggesting that HBV infection conferred resistance to chemotherapeutics that induced S-phase arrest by specifically inhibiting the activation of CHK2 response signaling in DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which accounts for 30–40% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), is an aggressive disease featuring heterogeneous genetic, phenotypic, and clinical characteristics1. The combination of rituximab and CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) has dramatically improved the outcome in DLBCL patients, with the 3-year event-free survival ranging from 65 to 80%2. However, approximately 30–40% of DLBCL patients will develop relapsed or refractory, which remains the major cause of mortality3. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the mechanisms of relapse and refractory to develop better chemotherapy options.

Virus infection is considered as a critical inducer of various diseases, especially cancer. Epstein–Barr virus has been proven to associate with the occurrence and progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and NHL4. Hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus (HBV) are also able to promote NHL5. HBV has infected 350 million people worldwide and is responsible for 340,000 cases of liver cancer and 500,000 to 1.2 million liver-related deaths annually. In addition, epidemiologic investigations in HBV endemic areas, including China, South Korea, and Japan, show that HBV infection is more common in NHL patients compared with the general population (19.94% vs. 7.18%)6–8. Importantly, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive DLBCL patients display poorer chemotherapy responses and shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with HBsAg-negative patients as an independent prognostic factor in DLBCL6,9. These reports mainly focus on investigating the clinical correlation between HBV infection and poor prognosis of DLBCL, but the exact mechanisms remain unexplored. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBX), has been reported to induce hepatocarcinogenesis by interacting with various signal transduction pathways, such as the SIRT10, Wnt/β-catenin11, signal transducer and activator of transcription12, and nuclear factor-κB pathway13 to induce hepatocarcinogenesis. The lymphotropic characteristic of HBV renders the HBX detectable in lymphoma tissue14–17. However, the role of HBX in causing progression and poor outcome in DLBCL patients has not been extensively studied.

Chemoresistance is the major cause of treatment failure, which results in relapsed and refractory DLBCL. The activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) allows cells self-repair to resist external damage via activating the downstream cyclins and apoptotic proteins, which results in chemoresistance18. DDR suppression is believed to sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapeutic treatments by causing cell death or senescence in the absence of checkpoints and efficient DNA repair19–23. On the other hand, DDR inhibition attenuates the cell cycle arrest that occurs during self-repair, which can reduce sensitivity to chemotherapeutic24,25. The role of DDR signals in the chemoresistance of DLBCL patients with HBV infection is still unclear.

After retrospectively analyzing 428 DLBCL patients, we found that HBV infection was closely associated with reduced responses to chemotherapy and poor OS and PFS of DLBCL patients, especially in germinal center B-cell type (GCB type) independent of its liver damage. Our results also showed that HBX conferred resistance to chemotherapeutics that induced S-phase arrest by specifically blocking the activation of checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) signaling in vitro and in vivo, which explained the poor outcome caused by HBV infection in DLBCL patients.

Results

HBV infection is correlated with poor prognosis of GCB-type DLBCL patients independent of its liver-damaging effects

We examined 428 DLBCL patients from January 2004 to July 2014 in Changhai Hospital (Shanghai, China) for HBsAg, and 93 cases were HBsAg positive. The HBV infection rate was much higher in DLBCL patients (21.7%) than that in the general population (7.18%)6. The clinical and pathological characteristics of DLBCL patients with or without HBV infection were shown in Table 1. The proportion of male patients with HBV infection (69.9%) was significantly higher than that without HBV infection (56.1%) (P = 0.017, Table 1). HBV-positive patients tended to be younger than HBV-negative patients (median age, 47.0 vs. 55.0, P = 0.032). There were no differences in cell of origin, Ki67 expression, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and proportions of rituximab included chemotherapy regimens between two groups, but HBV infection was closely associated with more advanced stages (P = 0.014, Table 1) and increased frequency of treatment failure (P = 0.028, Table 1), indirectly suggesting that HBV infection contributed to poor outcome.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative subjects in Changhai Hospital (n=428)

| Characteristics, n (%) | HBV (-), n = 335 (78.3%) | HBV (+), n = 93 (21.7%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.017 | ||

| Male | 188 (56.1%) | 65 (69.9%) | |

| Female | 147 (43.9%) | 28 (30.1%) | |

| Median age | 55.0 | 47.0 | 0.032 |

| Stage | 0.014 | ||

| I+II | 130 (38.8%) | 23 (24.7%) | |

| III+IV | 205 (61.2%) | 70 (75.3%) | |

| Cell of origin | 0.598 | ||

| Non-GCB | 190 (56.7%) | 57 (61.3%) | |

| GCB | 97 (29.0%) | 25 (26.9%) | |

| Not available | 48 (14.3%) | 11 (11.8%) | |

| Liver function | 0.002 | ||

| Normal | 320 (95.5%) | 79 (84.9%) | |

| Abnormal | 15 (4.5%) | 14 (15.1%) | |

| LDH | 0.082 | ||

| Normal | 231 (69.0%) | 55 (59.1%) | |

| Elevated | 104 (31.0%) | 38 (40.9%) | |

| Median Ki67 expression | 71.85% | 70.00% | 0.833 |

| Chemotherapy outcome | 0.028 | ||

| CR+PR | 246 (73.4%) | 57 (61.3%) | |

| Relapse+NR | 89 (26.6%) | 36 (38.7%) | |

| Rituximab included | 0.069 | ||

| No | 118 (35.2%) | 43 (46.2%) | |

| Yes | 217 (64.8%) | 50 (53.8%) |

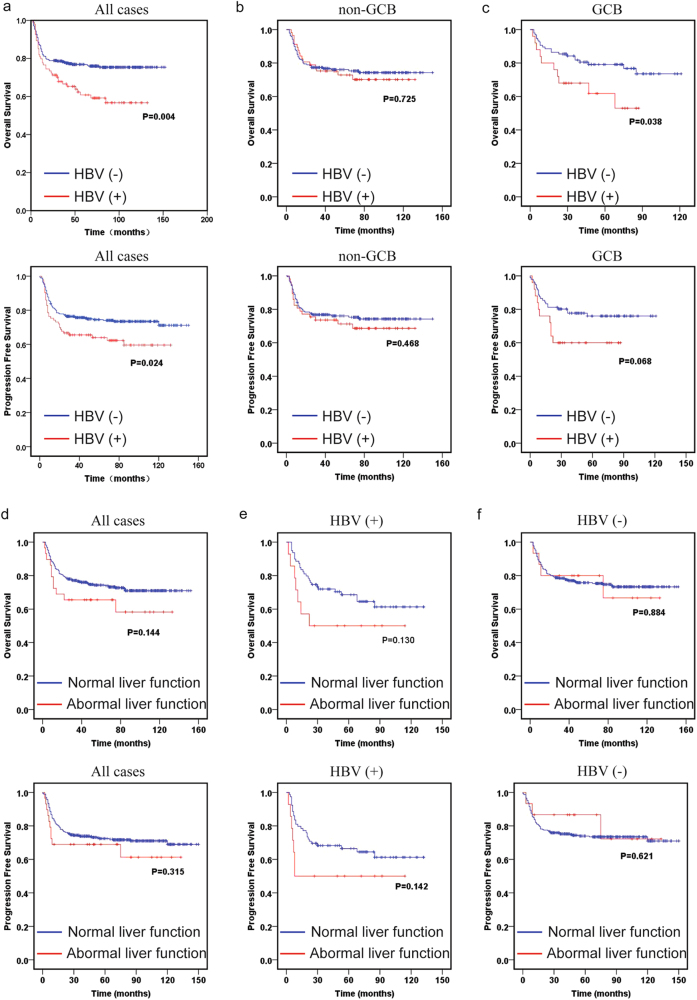

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the HBV-positive and HBV-negative cohorts revealed that HBV infection had a profound negative impact on the prognosis of DLBCL patients. Patients with HBV infection had significantly shorter OS and PFS than HBV-negative patients (Fig. 1a). After stratifying all the patients into GCB and non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) types, we found that DLBCL patients with HBV infection had significantly shorter OS in GCB type, but not non-GCB type, suggesting HBV infection mainly influenced the poor prognosis of GCB-type DLBCL patients (Figs. 1b, c). Increased hepatitis indicators, including alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, albumin, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin, were more frequently observed in whole course of HBsAg-positive subjects (Supplementary Fig. 1a), in spite that they received anti-viral treatment before chemotherapy until 6 months after chemotherapy. We surprisingly found that abnormal liver function showed no significant impact on OS and PFS of the whole group, the HBV-positive cohort, or the HBV-negative cohort (Figs. 1d–f). In accordance with previous studies14–17, the HBX protein could be detected in lymphoid tissues of HBV-infected patients (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Our results thus indicated that HBV infection might reduce the OS and PFS of DLBCL patients by directly affecting the biological properties of DLBCL cells independent of its liver-damaging effects.

Fig. 1. HBV infection associated with poor prognosis independent of its liver-damaging effects in GCB-type DLBCL.

a-c Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were performed to compare the OS and PFS of DLBCL patients with or without HBV infection in total cohort a, non-GCB type b, and GCB type c. d-f Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test were performed to compare the OS and PFS of DLBCL patients of normal and abnormal liver function in total cohort d, HBV-positive e, and HBV-negative f, DLBCL patients

HBX attenuates the proliferation inhibition of chemotherapeutics that induce S-phase arrest

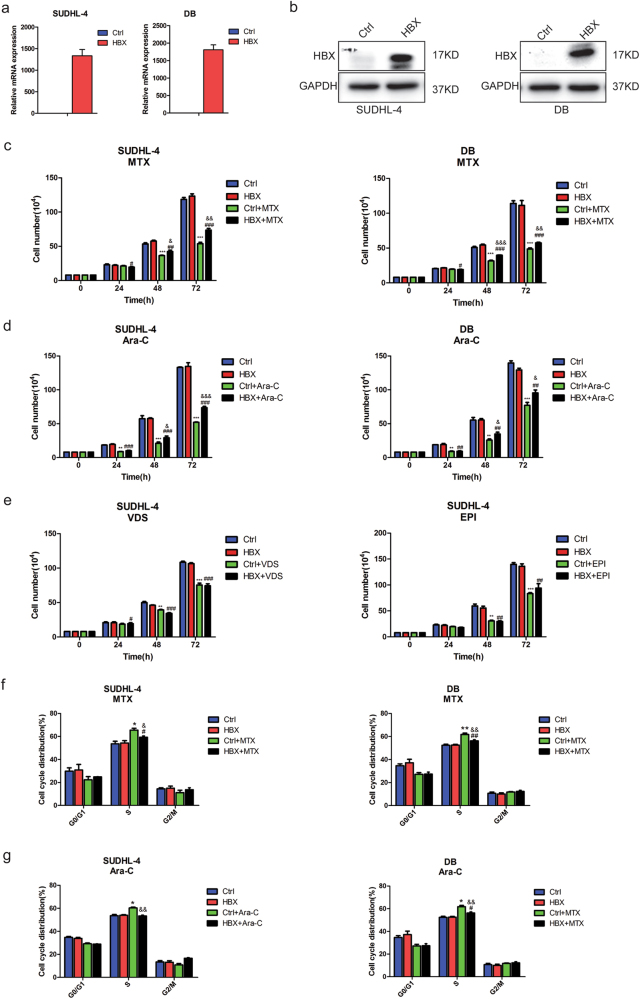

According to our clinical data analysis, the DLBCL patients with GCB-type HBV infection exerted shorter OS than that without HBV infection (Fig. 1c). We then focus on investigating the exact effects of HBX on the biological properties of GCB-type DLBCL cells. To analyze the effect of HBX on DLBCL cell growth, HBX was ectopically overexpressed in GCB-type DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL-4 and DB), which was verified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and western blotting (Figs. 2a, b). However, HBX-expressing DLBCL cells did not exhibit enhanced proliferation or differences in cell cycle distribution compared with control cells (Supplementary Figs. 2a and b). There was also no significant difference in the expression of cell cycle-related proteins upon exogenous expression of HBX compared with control cells (Supplementary Figs. 2c and d). Neither control cells nor HBX-expressing cells exhibited obvious apoptosis, as evaluated by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 2e). These data suggested that HBX had no significant effect on the proliferation, cell cycle distribution, or apoptosis of DLBCL cells.

Fig. 2. HBX attenuates the proliferation inhibition of chemotherapeutics that induce S-phase arrest.

a, b Ectopic overexpression of HBX in SUDHL-4 and DB cells was determined by qPCR a, and western blotting b. c, d Cell-counting assay for control or HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 and DB cells treated with MTX (4 ng/ml) or Ara-C (20 ng/ml); the cell numbers were measured at 24, 48, and 72 h. e Cell-counting assay for control or HBX-expressing SUDHL cells treated with VDS (0.6 ng/ml) or EPI (100 ng/ml); the cell numbers were measured at 24, 48, and 72 h. f, g Quantification of the cell cycle distributions in control and HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 and DB cells treated with MTX f, or Ara-C g, for 48 h. These results are shown as the mean ± SEM from triplicate experiments. “*” Represents Ctrl + agents versus Ctrl: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. “#” Represents HBX + agents versus HBX: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. “&” Represents HBX + agents versus Ctrl + agents: &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001

We further sought to investigate the effect of HBX on the response to chemotherapeutics. We tested the growth of control and HBX-expressing cells treated with the chemotherapeutic agents methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine (Ara-C), vindesine (VDS), and epirubicin (EPI) at a concentration of the IC50 value for 24, 48, and 72 h. Compared with control cells, SUDHL-4 and DB cells overexpressing HBX showed enhanced resistance to MTX and Ara-C after treatment for 48 and 72 h (Figs. 2c, d), whereas there was no significant difference in proliferation inhibition upon treatment with VDS and EPI (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, the cell cycle distributions analysis of control and HBX-expressing cells treated with or without MTX or Ara-C, which were characterized by inducing S-phase arrest, showed that HBX overexpression significantly attenuated the S-phase arrest in both SUDHL-4 and DB cells upon treatment with MTX and Ara-C (Figs. 2f, g). These findings indicated that HBX prevented the cytotoxicity and impaired the S-phase arrest of chemotherapeutics, which might explain why HBV infection cause poor outcome in DLBCL patients.

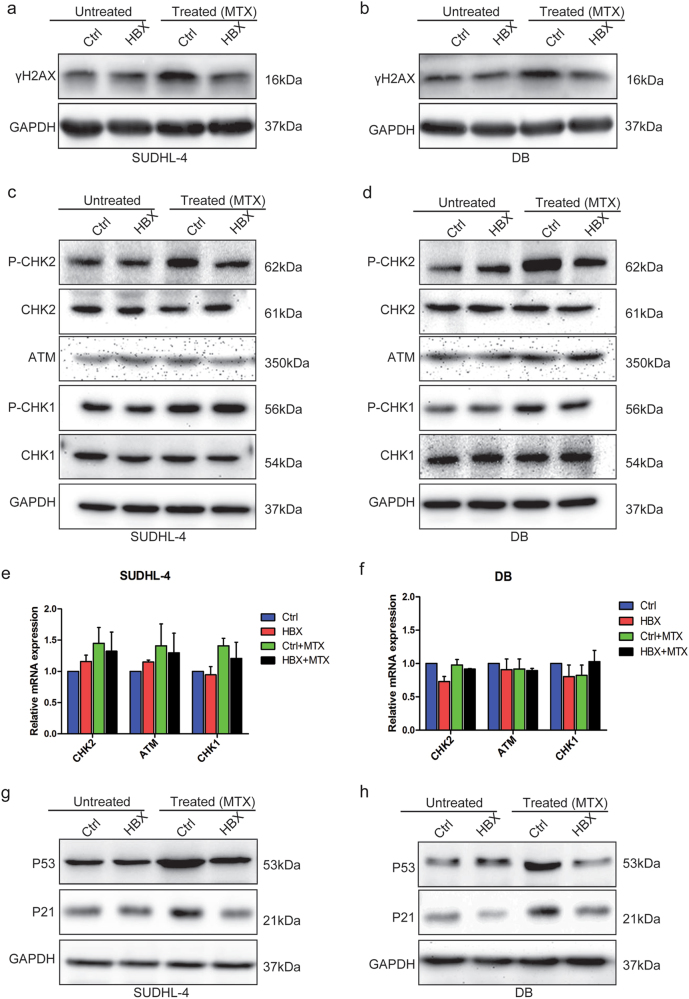

HBX specifically inhibits CHK2 phosphorylation

DDR has been reported to be intimately correlated with chemoresistance26. Phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX) is one of the early response to DNA damage, which is considered as a sensitive biomarker for DDR27,28. We found that HBX-expressing cells presented lower expression of γH2AX than control cells after treated with MTX, indicating that HBX expression attenuated the chemotherapeutic-induced DNA damage in DLBCL cells (Figs. 3a, b). To gain mechanistic insight into the molecules potentially involved in the decreased chemosensitivity resulting from HBV infection, alterations in two major DDR pathways ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/CHK2, and ATM and Rad-3 related (ATR)/checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) were assessed. The expression level of P-CHK1 was increased after treatment with MTX for 48 h in both control and HBX-expressing cells, but neither the baseline nor the post-treatment level of P-CHK1 was affected by overexpressing HBX. Unexpectedly, the expression level of P-CHK2 in control cells was markedly increased to a greater extent than that in HBX-expressing cells after treatment with MTX for 48 h, whereas no significant difference was observed in the baseline P-CHK2 level between control and HBX-expressing cells (Figs. 3c, d). Both the mRNA and protein levels of CHK1, CHK2, and ATM (an upstream kinase of CHK2) were largely unchanged, indicating that HBX might specifically inhibit the phosphorylation of CHK2 (Figs. 3e, f). Activated CHK2 signaling induced cell cycle arrest through activating P53 followed by P2129. Our results showed that the expression levels of P53 and P21, consistent with the expression level of P-CHK2, were less increased in HBX-overexpressing cells after treatment with MTX than that in control cells (Figs. 3g, h). Together, these results indicated that HBX overexpression appeared to specifically inhibit CHK2 phosphorylation caused by MTX treatment in DLBCL cells.

Fig. 3. HBX specifically inhibits CHK2 phosphorylation.

a, b Western blotting for γH2AX in control and HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 a, and DB b, cells with or without MTX treatment (4 ng/ml) for 48 h. c, d Western blotting for DDR proteins (P-CHK2/CHK2/ATM and P-CHK1/CHK1) in control and HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 c, and DB d, cells with or without MTX treatment (4 ng/ml) for 48 h. e, f The mRNA levels of DDR proteins (ATM, CHK2, and CHK1) were largely unchanged in control and HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 e, and DB f, cells with or without MTX treatment. g, h The expression of the P-CHK2 downstream genes P53 and P21 in control and HBX-expressing SUDHL-4 g, and DB h, cells with or without MTX treatment. The results are shown as the mean ± SEM from triplicate experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control

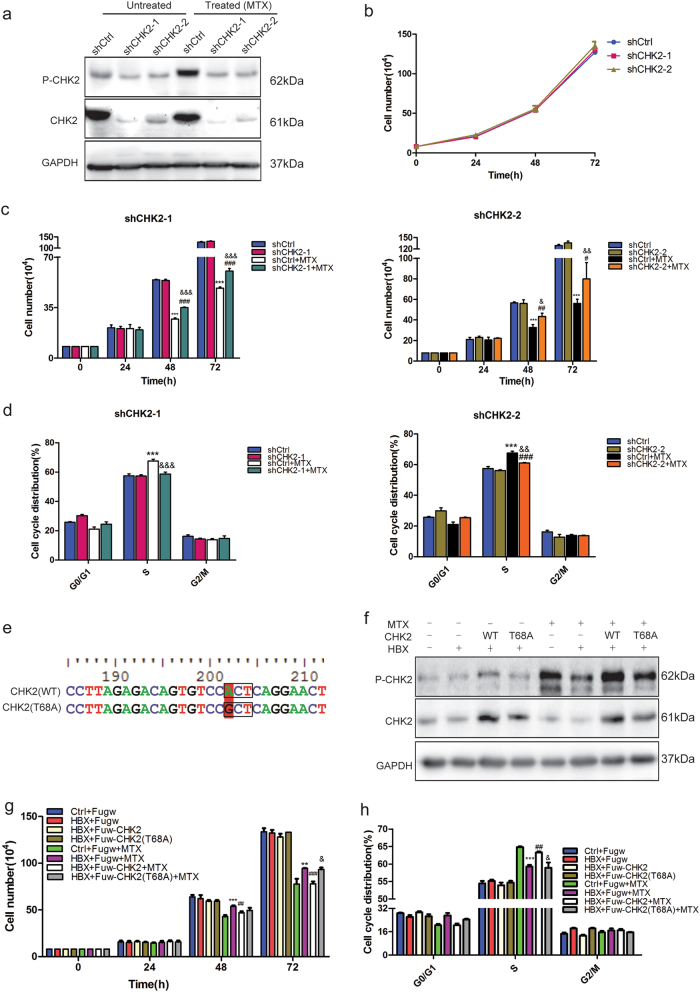

CHK2 phosphorylation rescues chemosensitivity in HBX-expressing cells

To investigate the functional role of P-CHK2 in chemoresistance, we attempted to downregulate CHK2 in SUDHL-4 cells using short hairpin RNA (shRNA). CHK2 depletion led to reduced expression of both P-CHK2 and CHK2 (Fig. 4a). The increase in P-CHK2 was less pronounced in shCHK2-1 and shCHK2-2 cells with MTX treatment compared with control cells (Fig. 4a). We further found that CHK2-depleted cells exhibited normal cell growth compared to control cells, consistent with previous reports (Fig. 4b)30. CHK2-depleted cells displayed a modest proliferation decrease and S-phase increase after MTX treatment for 48 h, which simulated the effects of HBX overexpression on proliferation and the proportion of cells in S-phase (Figs. 4c, d). As downregulation of CHK2 could result in enhanced chemoresistance after MTX treatment, we tried to reverse the reduced chemosensitivity of HBX-expressing cells by overexpressing wild-type CHK2 (WT) or an unphosphorylated CHK2 mutant (T68A) (Fig. 4e). An increase in the CHK2 level was detected after overexpressing both CHK2 (WT) and CHK2 (T68A), whereas increased expression of P-CHK2 was only observed after CHK2 (WT) overexpression (Fig. 4f). As expected, overexpressing CHK2 (WT) rather than mutant CHK2 (T68A) reversed the reduced proliferation inhibition and decreased S-phase arrest caused by HBX overexpression after MTX treatment (Figs. 4g, h). These results indicated that CHK2 could overcome HBX-induced chemoresistance and that this effect was dependent on its phosphorylation.

Fig. 4. CHK2 phosphorylation rescues chemosensitivity in HBX-expressing cells.

a The expression of CHK2 and P-CHK2 was measured by western blotting upon CHK2 depletion by two independent shRNAs with or without MTX treatment. b Depletion of CHK2 showed no significant effect on the proliferation of DLBCL cells. c Cell-counting assays for control, shCHK2-1 and shCHK2-2 SUDHL-4 cells with or without MTX (4 ng/ml) treatment at 24, 48, and 72 h. d Quantification of the cell cycle distributions of control and HBX-expressing cells with or without MTX treatment for 48 h. The results are shown as the mean ± SEM from triplicate experiments. “*” Represents shCtrl + MTX versus shCtrl: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. “#” Represents shCHK2 + MTX versus shCHK2: ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. “&” Represents shCHK2 + MTX versus shCtrl + MTX: &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001. e The schematic diagram of wild-type and mutant (T68A) CHK2. f Western blotting analysis for CHK2 and P-CHK2 in control and HBX-expressing cells transfected with Fuw (empty vector), Fuw-CHK2 (WT), or Fuw-CHK2 (T68A) with or without MTX treatment. GAPDH was used as a loading control. g, h Cell counting g, and cell cycle distribution analysis h, of the indicated groups with or without MTX treatment. The results are shown as the mean ± SEM from triplicate experiments. “*” Represents HBX + MTX versus Ctrl + MTX: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. “#” Represents HBX + CHK2(WT) + MTX versus HBX + MTX: ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. “&” Represents HBX + CHK2(T68A) + MTX versus HBX + CHK2(WT) + MTX: &P < 0.05

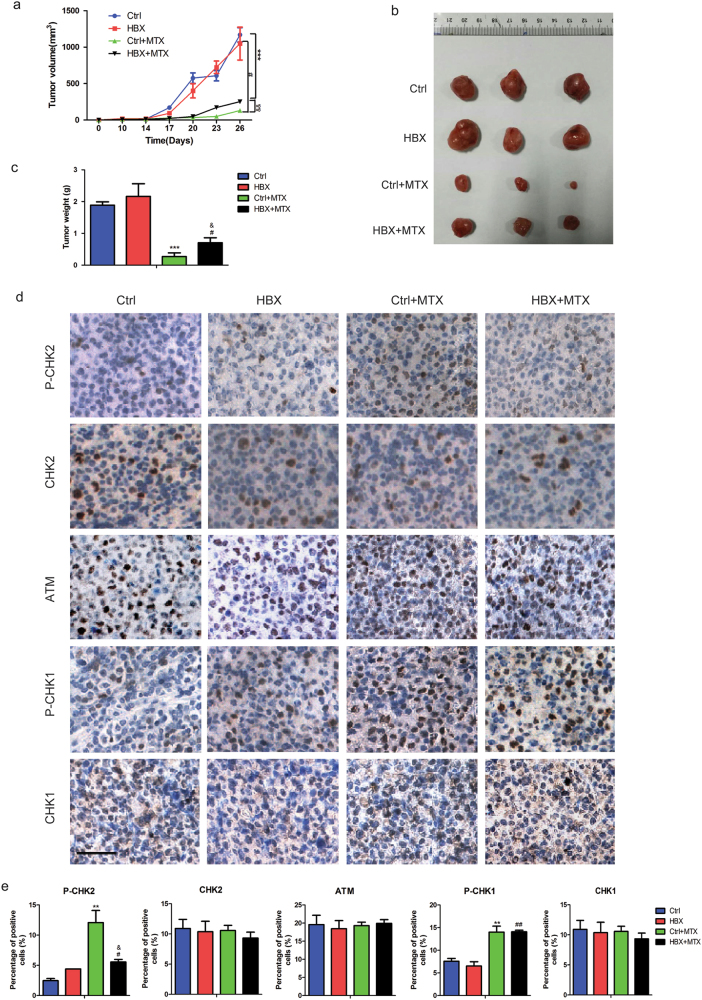

HBX confers resistance to chemotherapy in vivo

To further assess HBV infection as a mediator of chemoresistance, we examined the inhibition effect of MTX on control and HBX-expressing cells in vivo. Control and HBX-overexpressing DB cells were grafted into the nonobese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency disease (NOD-SCID) mice. Two weeks after injection, the mice were treated with MTX (10 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection every 3 days), and tumor sizes were measured (Fig. 5a). MTX treatment significantly reduced the tumor burden of mice injected with control cells compared with untreated mice (Figs. 5b, c). However, the tumor burden in mice injected with DB cells expressing HBX was not reduced as effectively as that in mice injected with control cells (Figs. 5b, c). The tumor specimens were then subjected to immunohistochemical staining to analyze the expression of DDR proteins, and our data showed that the expression level of P-CHK2 was mildly increased in tumors derived from HBX-expressing cells compared with those derived from control cells, whereas the increase extent of P-CHK1 was not affected by HBX overexpression (Figs. 5d, e). Consistent with the results in vitro, the expression levels of CHK2, ATM, and CHK1 were largely unchanged in both control and HBX-expressing cells with or without MTX treatment (Figs. 5d, e). These in vivo findings showed that HBV infection was a potent mediator of resistance to chemotherapeutics that induce S-phase arrest.

Fig. 5. HBX confers resistance to chemotherapy in vivo.

a Tumor volumes were measured every 3 days after day 14 post-injection in the indicated groups (n = 3 per group). b, c Representative images b, and weight statistics c, of tumors isolated from the mice for one of the batches at day 26 post-injection. d Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor sections from four groups using the indicated antibodies (P-CHK2, CHK2, ATM, P-CHK1, and CHK1). Scale bar, 25 μm. e Histogram statistics for the cells positive for the indicated proteins are shown. “*” Represents Ctrl + MTX versus Ctrl: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. “#” Represents HBX + MTX versus HBX: #P < 0.05,## P < 0.01. “&” Represents HBX + MTX versus Ctrl + MTX: &P < 0.05,&&P < 0.01

Discussion

Large-scale epidemiological investigations have suggested that HBV infection is positively correlated with the onset and progression of NHL. A large cohort study enrolling 603,585 individuals (53,045 HBV positive) in Korea indicated that the HBV-positive population had an increased risk of developing DLBCL throughout 14 years of follow-up31. It has also been reported that HBsAg-positive DLBCL patients exhibit more advanced disease stages, lower response to chemotherapy, and worse outcomes compared with HBsAg-negative DLBCL patients5,9. HBV-infected DLBCL patients are more likely to experience liver damage, while it is still conflicted that whether hepatic dysfunction serves as a prognosis factor for DLBCL during chemotherapy6,9. Our data demonstrated that HBsAg-positive DLBCL patients especially GCB type had lower chemotherapy efficacy and poorer outcomes than HBsAg-negative patients and that HBV-induced chemoresistance, but not hepatic dysfunction, contributed to the poor outcome.

Chemoresistance is widely known as a major cause of treatment failure18,32–34. HBV-infected DLBCL patients are more likely to exhibit advanced disease stages, which often preclude the first-line chemotherapies, including CHOP and R-CHOP. Our results showed that overexpression of the HBX protein resulted in resistance to the S-phase arrest-inducing chemotherapeutics (MTX and Ara-C) rather than two other drugs (VDS and EPI) in DLBCL cells, which was further confirmed by the impaired S-phase arrest in HBX-overexpressing DLBCLs treated with MTX or Ara-C. Thus, our findings indicated that HBV infection might result in lower sensitivity to MTX- or Ara-C-based second-line chemotherapy regimens including ESHARP (etoposide, Ara-C and prednisone), MA (MTX and Ara-C), DHAP (cisplatin, Ara-C and prednisone,and CODOX-MTX (cyclophosphamide, VDS, doxorubicin, and HD-MTX). Further investigations of autologous hematopoietic hepatocyte transplantation35 and other intensive chemotherapies, including R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)36,37, which have shown favorable effects in the treatment of aggressive DLBCL, might be of great benefit to DLBCL patients infected with HBV. Several studies have indicated that HBV infection results in the onset and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma because of its hepatotropic peculiarity38,39. HBV-DNA is consisted of four segments (S, P, C, and X). HBX, coded by HBV-X segment, is considered as a small “transcriptional activator” that stimulates transcription by activating Ras–Raf–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade and promotes cell proliferation by deregulating cell cycle checkpoint controls, then contributes to viral carcinogenesis40,41. HBX was also reported to promote hepatocarcinogenesis by regulating various signals10–12. However, our present data found that HBX had no effects on the cell growth, cell cycle distribution, or apoptosis of DLBCL cells, but reduced the chemosensitivity to drugs that induce S-phase arrest. The roles of other HBV segments in the DLBCL cell property needed to be further explored. Collectively, our study indicated a new function of HBX in regulating DLBCL cell chemoresistance and suggested that HBsAg-positive DLBCL patients would benefit less from MTX- or Ara-C-based chemotherapy than HBsAg-negative ones.

Much work has demonstrated that DDR is closely related to chemoresistance18,42,43. ATM/CHK2 and ATR/CHK1, two key pathways in DDR signaling, are activated upon DNA damage, leading to cell cycle arrest19–23. Our results showed that both MTX- and Ara-C-induced DNA damage dramatically activated CHK2 signaling and caused S-phase arrest to inhibit DLBCL cell growth. HBX overexpression significantly attenuated the activation of CHK2 signaling induced by S-phase arrest drugs, together with its downstream proteins P53 and P21, but did not affect the CHK1 pathway. CHK2 knockdown mimicked HBX-induced resistance to the S-phase arrest-inducing agents, and CHK2 overexpression overcame the resistance caused by HBX overexpression, indicating that CHK2 might serve as a potential mediator of HBX-induced chemoresistance and its de-phosphorylation caused by HBX impaired the S-phase arrest via inhibiting the downstream P53-P21 pathway in DLBCL. Furthermore, our present data showed that the chemosensitivity of HBX-expressing cells could be rescued by overexpressing wild-type CHK2, but not the unphosphorylated CHK2 mutant (T68A). HBX has previously been reported to modulate the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/AKT and MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signals in liver and pancreatic cancer44,45 and to activate CHK2 phosphorylation to delay the cell cycle in hepatocarcinogenesis46, suggesting that the direct regulation of protein phosphorylation is an important mechanism for HBX in carcinogenesis. Our findings first indicated that HBX specifically inhibited CHK2 phosphorylation, which conferred resistance to chemotherapeutics that induced S-phase arrest in DLBCL.

Evidence has shown that combining cytotoxic chemotherapeutics with pharmacological CHK2 inhibitors can prevent damaged cancer cells from arresting and improve therapeutic efficacy25,47,48. CHK2 inhibitors have already entered phase I & II clinical trials48,49. However, it has also been reported that CHK2 depletion reduces the chemosensitivity of various DNA-damaging agents including MTX in the treatment of Burkitt lymphoma24. High expression of CHK2 also results in a better response to platinum-based chemotherapy in ovarian cancer25. Our results showed that HBV infection caused resistance to S-phase arrest-inducing drugs in DLBCL by suppressing CHK2 phosphorylation, suggesting that HBV-infected DLBCL patients might not benefit from the use of CHK2 inhibitors.

In summary, our study uncovered the association between HBV infection and resistance to MTX- or Ara-C-based chemotherapy mediated by the inhibition of CHK2 response signaling, which provides new insight into the role of HBV in the chemoresistance of DLBCL patients. Therefore, HBV-infected DLBCL patients may benefit less from the use of S-phase arrest-inducing chemotherapeutics or CHK2 inhibitors. Further prospective investigations utilizing HBX-directed targeted therapy may help manage this challenge.

Materials and methods

Patients

We collected clinical data (name, gender, stages, international prognostic index (IPI) score, cell of origin, Ki67 expression, LDH, chemotherapy regiments, therapeutic evaluation, HBsAg status, liver indicator, OS, and PFS) of 428 cases DLBCL patients with or without HBV infection from January 2004 to July 2014 in Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Changhai Hospital. The diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma used current World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria. HBV infection status was determined by HBsAg. Stage criteria were based on the Ann Arbor staging criteria. The treatment efficacy was evaluated according to WHO curative standard.

Cell culture and chemotherapeutics

Human 293T cells and DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL-4 and DB) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. The following chemotherapeutics were used: MTX (Pfizer, Shanghai, China), Ara-C (Pharmacia, Shanghai, China), EPI (Hisun, Hangzhou, China), and VDS (Minsheng, Hangzhou, China).

Plasmid construction and stable transfection

The DNA fragments of HBX gene cloned from HepG2.2.15 cells were inserted into the pLVX-3× flag-IRES-ZsGreen1 vector, and the CHK2 DNA fragments cloned from SUDHL-4 cells were inserted into the Fuw vector. The CHK2 shRNAs were inserted into the pLKO.1 vector. Plasmid transfection was performed according to protocols supplied with the X-tremeGENE (Roche, Indianapolis, USA). Viral supernatant harvested 48 h after transfection was used to infect DLBCL cells in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml). Infected cells were selected with puromycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. The primers are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Cell growth assays and cell cycle analysis

Cells (8 × 104) were seeded in a 12-well plate, and the indicated amounts of chemotherapeutics were added. Cell numbers were measured by Cell Counter Star after 24, 48, and 72 h. The cells were harvested at 48 h and fixed in 1 ml of pre-cooled 70% ethanol for at least 8 h. The cells were stained with propidium iodide/RNase (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. Cell cycle distributions were evaluated by flow cytometry using a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and analyzed by FlowJo software.

Western blotting and immunohistochemistry

Western blotting and immunohistochemistry were performed according to standard procedures50. The following antibodies were used: anti-HBX (ab39716, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-P-CHK2 (2197S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-CHK2 (ab47433, Abcam), anti-ATM (ab199726, Abcam), anti-P21 (ab7960, Abcam), anti-P53 (BS1913, Bioworld, Minnesota, USA), anti-γH2AX (ab26350, Abcam), anti-P-CHK1 (2348S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-CHK1 (10362-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-CDK2 (SC-6248, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), anti-Cyclin D1 (SC-718, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GAPDH (SC-47724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HRP-Ms (#7074, Cell Signaling Technology), and HRP-Rb (#7076, Cell Signaling Technology).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using RNAiso (9109, Takara, Japan). First-strand complementary DNA synthesis was performed using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit (RR037A, Takara). The qPCR analysis was performed using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq TM (RR420A, Takara) with an Agilent Stratagene Mx3000P instrument. The GAPDH gene was employed as an internal control. The primer sequences used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Tumor xenografts

Five-week-old NOD-SCID mice were purchased from the National Resource Center for Rodent Laboratory Animals of China. Control and HBX-expressing DB cells (1 × 107 each), suspended in 100 μl of one part Matrigel and two parts DMEM, were subcutaneously injected into the left and right thigh of mice, respectively. On day 14 after tumor cells injection, the mice were monitored to assess the tumor volume using the formula 1/2 (length × width2) and injected intraperitoneally with MTX (10 mg/kg) every 3 days until day 26. The mice were sacrificed on day 26 post-injection. All experiments were carried out as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tongji University.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used to generate and compare the OS and PFS between different groups. We used the chi-square test and non-parametric test to compare categorical variables. The statistics were prepared using Excel and GraphPad Prism 5 software. The experiments were performed in triplicate and all data were presented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Normally distributed groups were compared by two-tailed Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570179 and 81170499 to J. C).

Supplementary Information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Xinying Zhao and Xudong Guo contributed equally to this work.

Edited by H-U Simon.

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41419-017-0097-1) contains supplementary material.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: optimizing outcome in the context of clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Blood. 2015;125:22–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfreundschuh M, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coiffier B, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.zur Hausen H, et al. EBV DNA in biopsies of Burkitt tumours and anaplastic carcinomas of the nasopharynx. Nature. 1970;228:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/2281056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcucci F, Mele A. Hepatitis viruses and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: epidemiology, mechanisms of tumorigenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Blood. 2011;117:1792–1798. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-275818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, et al. Concurrent infection of hepatitis B virus negatively affects the clinical outcome and prognosis of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after chemotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a hepatitis B endemic area: a case-control study. Japanese journal of cancer research. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2002;93:471–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takai S, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection in haematological malignancies and liver injury following chemotherapy. Eur. J. Haematol. 2005;74:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng L, et al. Hepatitis B virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: unique clinical features, poor outcome, and hepatitis B surface antigen-driven origin. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25061–25073. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srisuttee R, et al. SIRT1 sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells expressing hepatitis B virus X protein to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;429:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z, et al. HBx mutations promote hepatoma cell migration through the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer. Sci. 2016;107:1380–1389. doi: 10.1111/cas.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao B, Wang H, Lafdil F, Feng D. STAT proteins - key regulators of anti-viral responses, inflammation, and tumorigenesis in the liver. J. Hepatol. 2012;57:430–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong F, et al. The enhanced expression of death receptor 5 (DR5) mediated by HBV X protein through NF-kappaB pathway is associated with cell apoptosis induced by (TNF-alpha related apoptosis inducing ligand) TRAIL in hepatoma cells. Virol. J. 2015;12:192. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pontisso P, Vidalino L, Quarta S, Gatta A. Biological and clinical implications of HBV infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008;8:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, et al. High hepatitis B virus infection in B-cell lymphoma tissue and its potential clinical relevance. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2012;21:261–267. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283498e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Sayed GM, Mohamed WS, Nouh MA, Moneer MM, El-Mahallawy HA. Viral genomes and antigen detection of hepatitis B and C viruses in involved lymph nodes of Egyptian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Egyptian J. Immunol. 2006;13:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umeda M, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in lymphatic tissues in inactive hepatitis B carriers. J. Hepatol. 2005;42:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwok M, et al. Synthetic lethality in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with DNA damage response defects by targeting the ATR pathway. Lancet (London, England) 2015;385(Suppl 1):S58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–429. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Phosphorylation of Ser-20 mediates stabilization of human p53 in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13777–13782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 2000;14:278–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukas C, Falck J, Bartkova J, Bartek J, Lukas J. Distinct spatiotemporal dynamics of mammalian checkpoint regulators induced by DNA damage. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2003;5:255–260. doi: 10.1038/ncb945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang H, Pritchard JR, Williams RT, Lauffenburger DA, Hemann MT. A mammalian functional-genetic approach to characterizing cancer therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:92–100. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin LP, Hamilton TC, Schilder RJ. Platinum resistance: the role of DNA repair pathways. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:1291–1295. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squatrito M, et al. Loss of ATM/Chk2/p53 pathway components accelerates tumor development and contributes to radiation resistance in gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha H, et al. Wip1 directly dephosphorylates gamma-H2AX and attenuates the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4112–4122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonner WM, et al. GammaH2AX and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannell IG, et al. A pleiotropic RNA-binding protein controls distinct cell cycle checkpoints to drive resistance of p53-defective tumors to chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:623–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkema NG, et al. Checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) supports sensitivity to platinum-based treatment in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;133:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engels EA, Cho ER, Jee SH. Hepatitis B virus infection and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in South Korea: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:827–834. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70167-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur R, et al. Inhibition of demethylase KDM6B sensitizes diffuse large B-cell lymphoma to chemotherapeutic drugs. Haematologica. 2016;102:373–380. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.144964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DH, et al. FCGR3A gene polymorphisms may correlate with response to frontline R-CHOP therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2006;108:2720–2725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-009480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, et al. SYK-dependent tonic B-cell receptor signaling is a rational treatment target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:2230–2237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrich AM, et al. Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood. 2014;124:2354–2361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-578963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chihara, D. et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and mid-cycle high dose methotrexate for patients with systemic lymphoma and secondary CNS involvement. Br. J. Haematol 179, 851-854. (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Purroy N, et al. Long-term follow-up of dose-adjusted EPOCH plus rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) in untreated patients with poor prognosis large B-cell lymphoma. A phase II study conducted by the Spanish PETHEMA Group. Br. J. Haematol. 2015;169:188–198. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizzetto M, Ciancio A. Chronic HBV-related liver disease. Mol. Aspects. Med. 2008;29:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi YH, Shi CH. Molecular characteristics and stages of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3099–3105. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benn J, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus HBx protein activates Ras-GTP complex formation and establishes a Ras, Raf, MAP kinase signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10350–10354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benn J, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus HBx protein deregulates cell cycle checkpoint controls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11215–11219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carroll BL, Pulkoski-Gross MJ, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. CHK1 regulates NF-kappaB signaling upon DNA damage in p53- deficient cells and associated tumor-derived microvesicles. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18159–18170. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, Mosel AJ, Oakley GG, Peng A. Deficient DNA damage signaling leads to chemoresistance to cisplatin in oral cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2401–2409. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, et al. The hepatitis B virus X protein promotes pancreatic cancer through modulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;380:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han M, et al. Hepatitis B virus-induced hFGL2 transcription is dependent on c-Ets-2 and MAPK signal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:32715–32729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein activates the ATM-Chk2 pathway and delays cell cycle progression. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96:2242–2251. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlessi L, et al. Biochemical and cellular characterization of VRX0466617, a novel and selective inhibitor for the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6:935–944. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garrett MD, Collins I. Anticancer therapy with checkpoint inhibitors: what, where and when? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;32:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lord CJ, Garrett MD, Ashworth A. Targeting the double-strand DNA break repair pathway as a therapeutic strategy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:4463–4468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rijal S, et al. Inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase II (INPP4B) is associated with chemoresistance and poor outcome in AML. Blood. 2015;125:2815–2824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-603555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]