Key Points

Question

For patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection, does adjuvant chemotherapy confer a survival benefit compared with observation?

Findings

In this propensity score–matched analysis of 10 086 patients using the National Cancer Database, the median overall survival was significantly longer in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy compared with patients who underwent observation.

Meaning

In patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma, adjuvant chemotherapy following preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection may be warranted.

This propensity score–matched analysis uses National Cancer Database data on patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection to explore whether adjuvant chemotherapy confers a survival benefit compared with observation.

Abstract

Importance

Distant recurrence following preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma is common. Adjuvant chemotherapy may improve survival.

Objective

To compare adjuvant chemotherapy with postoperative observation following preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Propensity score–matched analysis using the National Cancer Database. We included adult patients who received a diagnosis between 2006 and 2013 of clinical stage T1N1-3M0 or T2-4N0-3M0 adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus or gastric cardia who were treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and curative-intent resection. Patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were matched by propensity score to patients undergoing postoperative observation.

Exposures

Adjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative observation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overall survival.

Results

We identified 10 086 patients (8840 [88%] male; mean [SD] age, 61 [9.5] years), 9272 in the postoperative observation group and 814 in the adjuvant chemotherapy group. Patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were younger (18-54 years: 252 [31%] vs 1989 [21%]; P < .001) and were more likely to have advanced disease (ypT3/4: 458 [62%] vs 3531 [46%]; P < .001; ypN+: 572 [72%] vs 3428 [39%]; P < .001), as well as shorter postoperative inpatient stays (>2 weeks: 94 [13%] vs 1589 [20%]; P < .001). A total of 732 patients in the adjuvant chemotherapy group were matched by propensity score to 3660 patients in the postoperative observation group. Adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved overall survival compared with postoperative observation (median survival: 40 months; 95% CI, 36-46 months vs 34 months; 95% CI, 32-35 months; stratified log-rank P < .001; hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88). Overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 88%, 47%, and 34% in the observation group, and 94%, 54%, and 38% in the adjuvant chemotherapy group, respectively. Adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a survival benefit compared with postoperative observation in most patient subgroups.

Conclusions and Relevance

For patients with locally advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and resection, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved overall survival. Our findings have important implications for the postoperative treatment of this patient group for which few data are available.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal (GE) cancer is an important and increasing cause of cancer burden globally. Despite advancements in multimodality therapy, GE cancer remains a leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide owing to its aggressive nature and poor prognosis. Multiple trials have demonstrated improved outcomes in patients with GE cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) followed by surgical resection. In particular, the phase 3 randomized Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer Followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) trial showed that preoperative CRT doubled the median survival from 24 to 49 months when compared with resection alone. The survival benefit was most pronounced in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma but was less definitive for those with adenocarcinoma (P = .07). In particular, approximately one-third of patients developed distant recurrence. The reduced duration and dose of systemic chemotherapy in preoperative CRT may have limited the regimen’s efficacy to prevent distant failure. For patients with GE adenocarcinoma, additional chemotherapy may reduce the risk of distant recurrence and improve survival.

Currently, there are few data to support the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) to preoperative CRT and resection for GE adenocarcinoma. Limited institutional studies have shown that the use of adjuvant therapy in patients with residual disease was associated with a modest survival benefit. In this study, we compared overall survival between AC and postoperative observation (POB) in patients with GE adenocarcinoma following preoperative CRT and resection.

Methods

Database and Patient Population

We identified patients with adenocarcinoma (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition [ICD-O-3], morphological codes 821, 822, 825, 826, 831, 848, 849, and 857) involving the distal esophagus (ICD-O-3 topographical codes C15.2 and C15.5) or gastric cardia (C16.0) in the National Cancer Database (NCDB) participant user data file between years 2006 and 2013. The NCDB is a national cancer registry receiving information from more than 1500 Commission-on-Cancer–accredited cancer programs in the United States. Approximately 70% of incident cancer cases in the United States are captured in the NCDB. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern. Informed consent of study patients was waived by the review board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

We included patients older than 18 years with clinical stage T1N1-3M0 or T2-4N0-3M0 according to the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) TNM staging manual. Only patients who received preoperative CRT and underwent a curative-intent resection were included. We excluded patients who underwent a palliative resection aimed at controlling symptoms or alleviating pain.

We abstracted patient information (patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, income, and insurance type) and tumor data (year of diagnosis, location, histologic type, grade, clinical and pathological UICC/AJCC TNM stages, tumor extension, and involved lymph nodes). In the NCDB, comorbidity conditions are mapped from up to 10 secondary diagnosis codes. Patients who received a diagnosis between 2006 and 2009 were staged initially using the sixth edition of the UICC/AJCC TNM staging manual. We adjusted their staging to reflect the stage categories of the manual’s seventh edition. A more detailed description of these adjustments can be found elsewhere. Treatment data on the type of resection, the time from diagnosis to resection, and receipt of preoperative and/or postoperative chemotherapy and radiation were available. Per the NCDB participant user data file data dictionary, pre- and postoperative chemotherapy reflect the receipt of at least 2 courses of chemotherapy pre- and postoperatively, respectively. The NCDB data dictionary also specifies that treatment information recorded in the NCDB database pertain to first-course treatment only. Thus, treatment given for disease progression or recurrence is excluded. In addition, we abstracted data on number of lymph nodes examined, resection margins, and early postoperative outcomes including length of hospital stay, 30-day unplanned readmissions, and 30-day and 90-day mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Conditional Landmark Analysis

We used conditional landmark analysis to account for the immortal time bias in the AC group. The bias reflects the fact that patients in the AC group must have survived the postoperative period, as well as the period during which they received at least 2 cycles of AC. As such, we included in our analysis only patients who survived at least 90 days postoperatively. Our choice of landmark time at postoperative 90 days relates to this period’s significance as a surgical performance and quality of care metric.

Estimation of Missing Data

We used multiple imputation by chained equations to impute missing data for hospital teaching status (0.3% missing), race (0.8%), insurance type (1.8%), income (1.2%), diagnosis to resection time (1.5%), tumor grade (14.4%), pathological T stage (17.1%), pathological N stage (5.4%), resection margin (3.7%), number of lymph nodes examined (5.2%), postoperative length of stay (14.2%), and unplanned 30-day readmissions (3.7%). We used baseline information, as well as treatment allocation variables, to generate 20 imputed data sets.

Propensity Score Matching

We used propensity score matching to compare overall survival between the AC and POB groups. We estimated, in each imputed data set, the propensity score, that is, the conditional probability of receiving AC, using a multivariable logistic regression model. In this model, we explored clinically relevant variables, as well as factors associated either with the receipt of AC or with overall survival to estimate the propensity scores. These variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, comorbidity score, income, insurance type, facility type, time from diagnosis to resection, tumor location, grade, clinical T and N stages, pathological T and N stages, number of lymph nodes examined, resection margins, length of stay, and 30-day unplanned readmissions. The latter 2 variables were included to account for selection bias related to the fact that patients with postoperative complications are less likely to receive AC. The C statistic for the logistic regression models ranged between 0.73 and 0.74 among the 20 imputed data sets. The estimated propensity scores from all imputed data sets were then combined using the mean of the individual estimates in each data set, according to the Rubin rule.(pp75-81)

Within the 2 tumor location categories, distal esophagus and gastric cardia, a 1-to-5 (AC to POB) matching by propensity score, without replacement, was performed using the nearest neighbor method within a caliper of 0.1. We performed matching separately within each tumor location stratum primarily because surgical resections are expectedly less variable within each tumor location stratum; therefore, postoperative complications are more likely to be homogenous. In addition, specific details about the type of resections are lacking in the NCDB. The choice of a 1-to-5 matching ratio was determined by maximizing this ratio while maintaining a 90% match rate in the AC group. Propensity score matching was performed using the Matching package in R, version 3.3.1 (R Foundation). Balance in the baseline covariates after matching was examined using standardized differences. An absolute standardized difference less than 0.1 implies an adequate match. Balance in baseline variables was also evaluated using the likelihood ratio test following conditional logistic regression modeling of the management approach (AC, POB) in the matched data.

Survival Data Analysis

We used Kaplan-Meier curves to estimate the overall survival from the time of diagnosis in the AC and POB groups in the matched data. A log-rank test stratified on matched patients was used to compare survival in both groups. The association between postoperative management approach, AC vs POB, and overall survival was evaluated using a Cox proportional hazards model stratified on matched patients. The assumption of proportional hazards was evaluated by examining the scaled Schoenfeld residuals.

We evaluated for heterogeneity in treatment effects within baseline covariates using tests for interaction. We also estimated the treatment effect using a Cox regression model within each level of each covariate. The following covariates were evaluated: tumor location, pathologic T stage, pathologic N stage, and resection margin status.

Sensitivity Analyses

One of the criticisms of propensity score matching is the reduction of sample size, which can lead to a decrease in power. To address this possibility, we evaluated the association between the postoperative management plan and overall survival in the entire patient cohort using propensity score weighting. The weights were constructed to estimate the mean treatment effect in the AC group, analogous to the treatment effect estimated using matching by propensity score.(pp239-255) The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy compared with postoperative observation did not appreciably change in direction or significance (data not shown); therefore, we report only the results of the primary analysis, matching by propensity score.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to quantify the effect of the unmeasured postoperative complications, which is not available in the NCDB and may affect overall survival, on the association between the postoperative management approach (AC vs POB) and overall survival. To do so, we assessed the extent to which the proportion of postoperative complications needs to be imbalanced between AC and POB to eliminate the treatment effect of AC (ie, the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval [CI] for the hazard ratio [HR] crosses 1). We reestimated the HR and its 95% CI, over a range of hypothetical proportions, elicited from the literature and expert opinion, of postoperative complications in the AC and POB groups—such that the proportion of complications is assumed to be higher in the POB group—and for various estimates of the association between postoperative complications and overall survival.

In this study, significance level was .05 for all hypothesis tests. Apart from propensity score matching, all analyses were conducted using STATA, version 14.

Results

Baseline Characteristics in the Original (Unmatched) Data

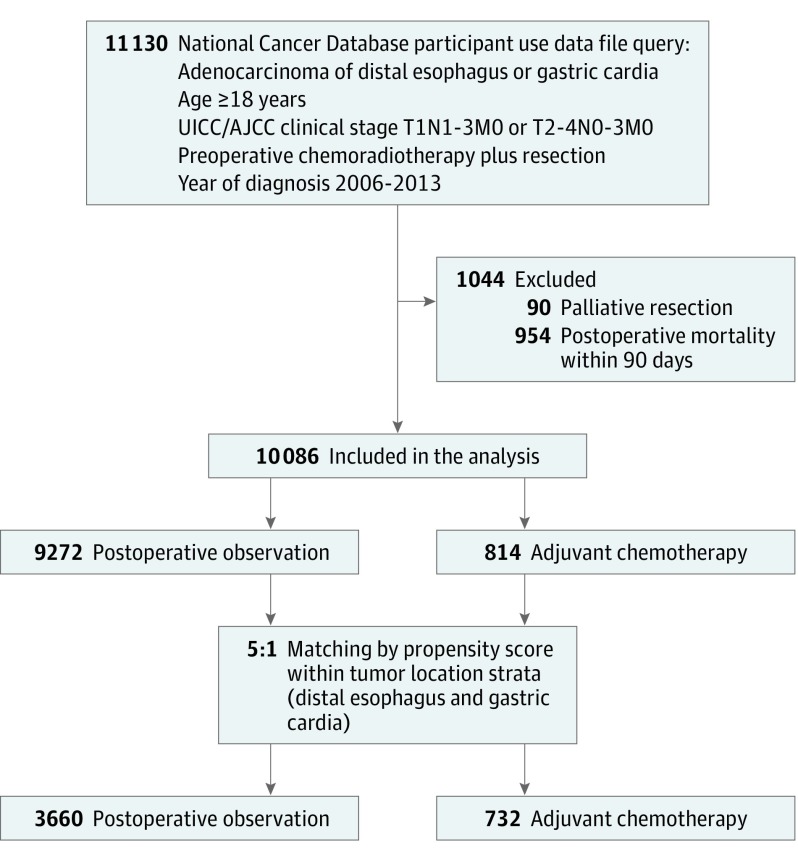

Between 2006 and 2013, we identified 11 130 adult patients with adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus or gastric cardia who completed preoperative CRT and curative-intent resection (Figure 1). A total of 10 086 patients were included in the analysis after the exclusion criteria were applied; 6317 (63%) patients had tumor involving the distal esophagus and 3769 (37%) patients had disease at the gastric cardia. There were 9272 (92%) patients in the POB group and 814 (8%) patients in the AC group. The Table summarizes select baseline characteristics of patients in each treatment group in the original (unmatched) data (a complete list of baseline characteristics can be found in eTable 1 in the Supplement). Compared with patients in the POB group, patients who received AC were younger (252 [31%] vs 1989 [21%] for patients aged 18-54 years; P < .001) but had similar comorbidity profiles (Charlson/Deyo score of 0: 617 [76%] vs 6858 [74%]; P = .50). The AC group was more likely to have private insurance (513 [64%] vs 4826 [53%]; P < .001), advanced disease (ypT3/4: 458 [62%] vs 3531 [46%]; P < .001; ypN+: 572 [72%] vs 3428 [39%]; P < .001), an adequate number of examined lymph nodes (15 lymph nodes: 381 [49%] vs 3533 [40%]; P < .001), positive resection margin (78 [10%] vs 440 [5%]; P < .001), a shorter diagnosis to resection time (>5 months: 130 [16%] vs 2503 [27%]; P < .001), and shorter inpatient length of stay (>2 weeks: 94 [13%] vs 1589 [20%]; P < .001).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on Cancer; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control.

Table. Comparison of Select Baseline Variables Between the Postoperative Observation (POB) and Adjuvant Chemotherapy (AC) Groups in the Original (Unmatched) and the Matched Data Sets.

| Variable | Original (Unmatched) Dataa | Matched Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Valueb | No. (%) | Sdiff | P Valuec | |||

| POB (n = 9272) |

AC (n = 814) |

POB (n = 3660) |

AC (n = 732) |

||||

| Age, y | |||||||

| 18-54 | 1989 (21) | 252 (31) | <.001 | 1018 (28) | 197 (27) | 0.02 | .95 |

| 55-59 | 1518 (16) | 142 (17) | 654 (18) | 134 (18) | 0.01 | ||

| 60-64 | 1987 (21) | 191 (23) | 873 (24) | 174 (24) | 0.00 | ||

| ≥65 | 3778 (41) | 229 (28) | 1115 (30) | 227 (31) | 0.01 | ||

| Male sex | 8111 (87) | 729 (90) | .08 | 3273 (89) | 654 (89) | 0.00 | .95 |

| White race | 8713 (95) | 755 (93) | .04 | 3396 (94) | 681 (93) | 0.01 | .74 |

| Charlson/Deyo score | |||||||

| 0 | 6858 (74) | 617 (76) | .50 | 2756 (75) | 552 (75) | 0.00 | .94 |

| 1 | 1965 (21) | 162 (20) | 753 (21) | 148 (20) | 0.01 | ||

| ≥2 | 449 (5) | 35 (4) | 151 (4) | 32 (4) | 0.01 | ||

| Diagnosis to resection time, mo | |||||||

| <4 | 3323 (36) | 413 (51) | <.001 | 1727 (48) | 340 (47) | 0.02 | .90 |

| 4-5 | 3304 (36) | 261 (32) | 1240 (34) | 252 (35) | 0.01 | ||

| >5 | 2503 (27) | 130 (16) | 636 (18) | 130 (18) | 0.01 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | |||||||

| Well | 374 (5) | 27 (4) | <.001 | 121 (4) | 27 (4) | 0.02 | .74 |

| Moderate | 3235 (41) | 242 (34) | 1157 (36) | 225 (35) | 0.02 | ||

| Poor | 4167 (53) | 439 (61) | 1873 (58) | 383 (59) | 0.02 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 135 (2) | 12 (2) | 61 (2) | 9 (1) | 0.04 | ||

| Pathologic T stage | |||||||

| ypT0 | 1429 (19) | 70 (10) | <.001 | 304 (10) | 69 (10) | 0.03 | .93 |

| ypT1 | 1238 (16) | 69 (9) | 328 (10) | 67 (10) | 0.01 | ||

| ypT2 | 1431 (19) | 138 (19) | 578 (18) | 128 (19) | 0.02 | ||

| ypT3 | 3282 (43) | 433 (59) | 1807 (58) | 373 (57) | 0.02 | ||

| ypT4 | 249 (3) | 25 (3) | 119 (4) | 23 (3) | 0.02 | ||

| Pathologic positive N stage | 3428 (39) | 572 (72) | <.001 | 2483 (70) | 490 (69) | 0.04 | .17 |

| Pathologic complete response | 1142 (15) | 39 (5) | <.001 | 169 (5) | 39 (6) | 0.02 | .78 |

| Lymph nodes examined ≥15 | 3533 (40) | 381 (49) | <.001 | 1619 (47) | 334 (47) | 0.01 | .96 |

| R1 resection | 440 (5) | 78 (10) | <.001 | 285 (8) | 57 (8) | 0.01 | .95 |

| 30-d Readmission | 497 (6) | 38 (5) | .38 | 183 (5) | 33 (5) | 0.02 | .61 |

Abbreviation: Sdiff, standardized difference.

Missing data not included.

P value for the χ2 test.

P value for likelihood ratio test following conditional logistic regression.

Overall Survival in the Matched Data

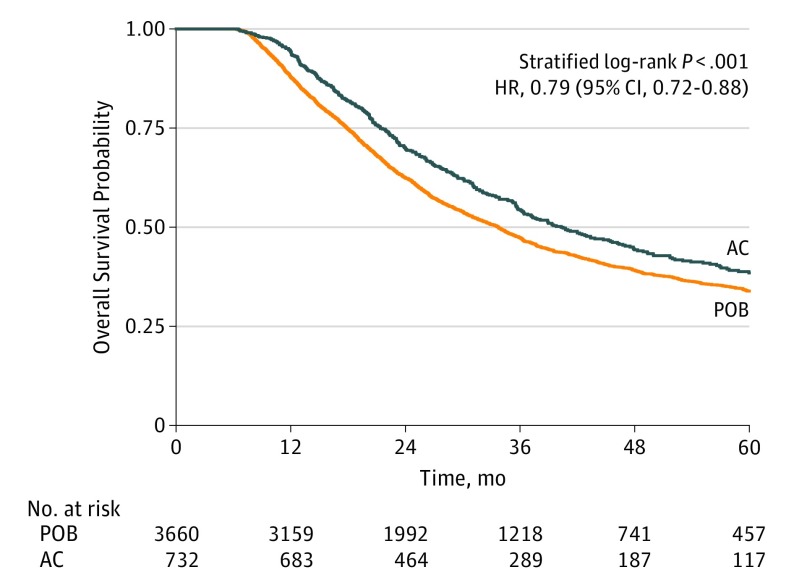

Following the 5-to-1 matching by propensity score, 732 patients in the AC group were matched to 3660 patients in the POB group, yielding a 90% match rate. The baseline covariates between the 2 treatment groups in the matched data were adequately matched as evidenced by small standardized differences (0.04) and nonsignificant likelihood ratio tests (Table). The median follow-up of the entire matched cohort was 27 months (interquartile range [IQR], 17-44 months). For most patients (3559 [82%]), the time from diagnosis to resection was less than 5 months. Median duration of preoperative therapy was 5.6 weeks (IQR, 5.1-6.0 weeks) in both groups. The median overall survival was 34 months (95% CI, 32-35 months) in the POB group and 40 months (95% CI, 36-46 months) in the AC group (stratified log-rank P < .001) (Figure 2). The overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 88%, 47%, and 34% in the POB group, and 94%, 54%, and 38% in the AC group, respectively. The addition of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting was associated with improved overall survival compared with observation only (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve for Overall Survival Between Patients in the Postoperative Observation Group (POB) and Patients in the Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group (AC) in the Matched Data.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

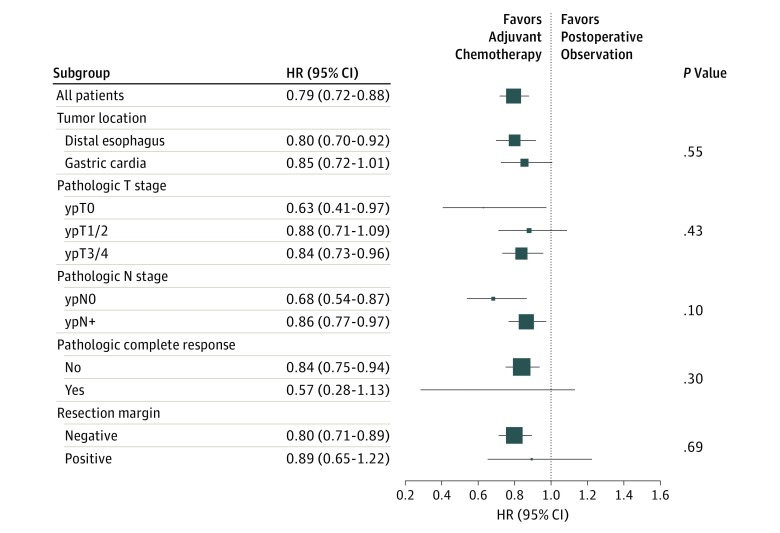

There was no significant evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect among the tumor-specific covariate levels (P ≥ .10 for interaction among all examined covariates) (Figure 3). In the subgroup analysis, AC was associated with improved overall survival compared with POB in most examined baseline tumor-specific covariates. The survival benefit was largest, although not statistically significant, in patients with pathologic complete response (ypT0N0; HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.28-1.13)—a relevant finding given that this patient group has a 23% risk of recurrence.

Figure 3. Mortality Hazard Ratios According to Baseline Covariates.

Marker size is proportional to the precision of the hazard ratio (HR) estimate. CRT indicates chemoradiotherapy; P values are for interaction.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results from the sensitivity analysis performed to quantify the effect of postoperative complications, an unmeasured confounder, on the association between AC and survival are presented in eTable 2 in the Supplement. The survival benefit of AC over POB remained significant over a range of hypothetical estimates of postoperative complications. In other words, postoperative complications would need to be as high as 50% in the POB group and as low as 5% in the AC group as well as the HR for postoperative complications on survival to be at least 1.5—all of which are reasonably extreme values—for the impact of unmeasured postoperative complications to nullify the treatment effect of AC on overall survival (ie, render the hazard ratio for AC vs POB not significant).

Discussion

Multiple trials have shown that preoperative CRT and resection for GE cancer improves the rate of complete pathologic response, local tumor control, and margin-negative resection along with overall survival. However, few data exist regarding the use of adjuvant chemotherapy after resection. In this study, we showed that adjuvant therapy was associated with improved overall survival compared with POB in patients with GE adenocarcinoma who completed preoperative CRT and curative-intent resection. This survival benefit was nearly uniform across patient subgroups.

The rationale for adjuvant chemotherapy is to decrease the rate of distant recurrence to improve survival. The risk of distant disease recurrence is considerable in patients undergoing preoperative CRT and resection for GE cancer, with nearly 50% of patients demonstrating distant recurrence in some trials. The reduced chemotherapy dose and/or the protracted chemotherapy course in preoperative CRT regimens may partly explain more frequent recurrence and worse survival observed in patients undergoing observation. We found that AC was used in only 8% after preoperative CRT and resection. Patients receiving AC demonstrated higher-risk features including advanced disease stage, greater positive resection margin rate, and lower rates of pathologic complete response.

The limited data available regarding the use of any postoperative therapy, including chemotherapy, following preoperative CRT and resection consists of retrospective studies and single-arm trials. The ability to administer postoperative therapy is limited by toxicity. Adelstein et al and Rodriguez et al investigated various perioperative CRT protocols for patients with esophageal cancer. Despite adjusting the radiation schedules and chemotherapy regimens, overall survival remained poor and perioperative mortality approached 18%. Recently, Heath et al and Kim et al demonstrated that the administration of postoperative therapy was feasible and suggested a potential survival benefit. However, the single-arm designs and small sample sizes of these studies preclude a definitive conclusion regarding the superiority (or inferiority) of adjuvant therapy over POB.

Our findings reflect current practice patterns at NCDB institutions during the study period rather than treatment within a clinical trial setting. As such, there is likely substantial heterogeneity in patient selection, preoperative regimens, patient follow-up, and radiotherapy and surgical quality control. These factors may dilute the estimated treatment effect between AC and POB, reflecting an average effect of a mixture of AC regimens.

Although the NCDB lacks details about the specific chemotherapy received, we assume that the regimens were variable throughout the study period. Cisplatin and fluorouracil were more likely to have been administered in the early years of this study because those agents were frequently used in preoperative CRT trials for esophageal cancer, whereas carboplatin and paclitaxel were more frequent following the publication of the CROSS trial in 2012. The difference in the type of systemic chemotherapy and the exposure period in the preoperative setting may have an impact on the effect of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival. However, there was no differential treatment effect between the period prior to the year 2012 and the period 2012 to 2013 (P of the interaction term = .32), suggesting that the probable wide use of CROSS regimens did not drastically change the treatment effect of AC on survival. Notably, our study cannot account for treatment of recurrent disease. Possible variations in second-line treatment between AC and POB may affect survival, and, as a result, our conclusions. However, the impact of this is likely minor. Extrapolating from data on unresectable GE cancer, prognosis for recurrent disease is invariably dismal, and available treatment regimens unfortunately do not impart meaningful differences in survival.

The estimated effect of AC on overall survival is subject to selection bias and immortal time bias given that the study was observational. We used matching by propensity score to account for the former and conditional landmark analysis to mitigate the effects of the latter. Importantly, we addressed selection bias related to postoperative complications in the following ways: (1) we excluded patients who died within 90 days postoperatively, (2) we included postoperative length of stay and unplanned readmission in estimating the propensity score, and (3) we matched by propensity score within the strata of tumor location. We also showed using sensitivity analysis that the survival benefit of AC was robust to large ranges of imbalance in an unmeasured confounder such as postoperative complications. Performance status is also a potential source of selection bias that is not collected in NCDB.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. We used propensity scoring and conditional landmark analysis to mitigate selection bias and immortal time bias. Another important limitation is that the NCDB lacks detailed information on certain variables, such as detailed chemotherapy regimens, that would provide more granular data for analysis.

Conclusions

The findings from this study support adding chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting to improve overall survival in patients with GE adenocarcinoma who complete preoperative CRT and resection. These findings, while not confirmatory, provide compelling motivation to explore the potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in a randomized clinical trial. Given the moderate difference in overall survival between patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy and those who receive POB, as well as the lack of data on the type and period of adjuvant chemotherapy, a 2-arm phase 2 trial design using recurrence-free survival as a primary end point is an appealing first step. The success of such a trial will depend primarily on the choice of preoperative CRT and adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, the feasibility of delivering these regimens, and their tolerability in this patient population.

eTable 1. Comparison of baseline variables between the observation and adjuvant chemotherapy groups in the original (unmatched) and the matched datasets

eTable 2. Sensitivity analysis

References

- 1.Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, et al. ; Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration . The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):505-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, et al. . Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):851-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, Kelly A, Keeling N, Hennessy TP. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):462-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. . Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1086-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Hagen P, Hulshof MCCM, van Lanschot JJB, et al. ; CROSS Group . Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2074-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. ; Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group . Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):681-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oppedijk V, van der Gaast A, van Lanschot JJB, et al. . Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heath EI, Burtness BA, Heitmiller RF, et al. . Phase II evaluation of preoperative chemoradiation and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for squamous cell and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):868-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim GJ, Koshy M, Hanlon AL, et al. . The benefit of chemotherapy in esophageal cancer patients with residual disease after trimodality therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(2):136-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Surgeons National Cancer Data Base. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. Accessed January 25, 2016.

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH; Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration . Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: data-driven staging for the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Cancer staging manuals. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3763-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biondi A, Hyung WJ. Seventh edition of TNM classification for gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4338-4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strong VE, D’Amico TA, Kleinberg L, Ajani J. Impact of the 7th Edition AJCC staging classification on the NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology for gastric and esophageal cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(1):60-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giobbie-Hurder A, Gelber RD, Regan MM. Challenges of guarantee-time bias. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2963-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damhuis RA, Wijnhoven BP, Plaisier PW, Kirkels WJ, Kranse R, van Lanschot JJ. Comparison of 30-day, 90-day and in-hospital postoperative mortality for eight different cancer types. Br J Surg. 2012;99(8):1149-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talsma AK, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Wijnhoven BPL, Van Lanschot JJB. The 30-day versus in-hospital and 90-day mortality after esophagectomy as indicators for quality of care. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat Med. 2014;33(7):1242-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekhon J. Multivariate and propensity score matching software with automated balance optimization: the Matching package for R. J Stat Softw. 2011;42(7):1-52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 24.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine—reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2189-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo S, Fraser MW. Propensity Score Analysis: Statistical Methods and Applications. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin DY, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA. Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies. Biometrics. 1998;54(3):948-963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitra N, Heitjan DF. Sensitivity of the hazard ratio to nonignorable treatment assignment in an observational study. Stat Med. 2007;26(6):1398-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon J-P, et al. . Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1715-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fields RC, Strong VE, Gönen M, et al. . Recurrence and survival after pathologic complete response to preoperative therapy followed by surgery for gastric or gastrooesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(12):1840-1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Gebski V, et al. ; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group; Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group . Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for resectable cancer of the oesophagus: a randomised controlled phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(9):659-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adelstein DJ, Rice TW, Becker M, et al. . Use of concurrent chemotherapy, accelerated fractionation radiation, and surgery for patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80(6):1011-1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adelstein DJ, Rice TW, Rybicki LA, et al. . A phase II trial of accelerated multimodality therapy for locoregionally advanced cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction: the impact of clinical heterogeneity. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30(2):172-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez CP, Adelstein DJ, Rice TW, et al. . A phase II study of perioperative concurrent chemotherapy, gefitinib, and hyperfractionated radiation followed by maintenance gefitinib in locoregionally advanced esophagus and gastroesophageal junction cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(2):229-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, Iannettoni M, Forastiere A, Strawderman M. Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(2):305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohtsu A, Shimada Y, Shirao K, et al. ; Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205) . Randomized phase III trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer: the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205). J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. ; V325 Study Group . Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):4991-4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Comparison of baseline variables between the observation and adjuvant chemotherapy groups in the original (unmatched) and the matched datasets

eTable 2. Sensitivity analysis