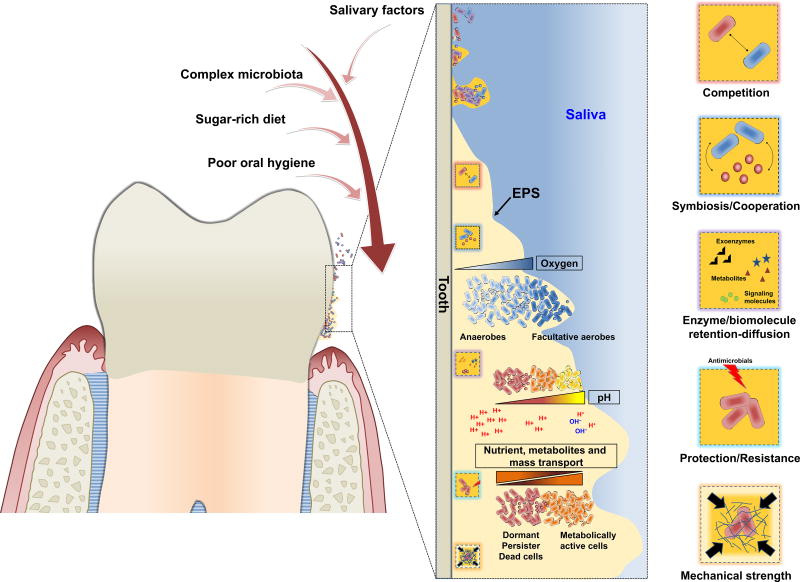

Figure 2. The biofilm properties: assembling a complex microenvironment.

In the oral cavity, a diet rich in sugar, particularly sucrose, provide substrate for the production of extracellular polysaccharides, which forms the core of the extracellular matrix in cariogenic biofilms. The matrix drastically changes the physical and biological properties of the biofilm. The exopolysaccharides enhance microbial adhesion-cohesion and accumulation on the tooth surface, while forming a polymeric matrix that embeds the cells. The matrix provides a multi-functional scaffold for structured organization and stability of the biofilm microbial community, where microorganisms co-exist and compete with each other. The diffusion-modifying properties of the matrix combined with the metabolic activities of embedded organisms help create a variety of chemical microenvironments, including localized gradients of oxygen and pH. Furthermore, the matrix can trap or sequester a diverse range of substances, including nutrients, metabolites and quorum sensing molecules. Similarly, enzymes can be retained and stabilized, transforming the matrix into a de facto external digestive system [1]. These properties provide the distinctive characteristics of the biofilm lifestyle, including mechanical stability, spatial and chemical heterogeneity and drug tolerance [1].