Abstract

BACKGROUND

Young people may experience school-based violence and bullying victimization related to their gender expression, independent of sexual orientation identity. However, the associations between gender expression and bullying and violence have not been examined in racially and ethnically diverse population-based samples of high school students.

METHODS

This study includes 5469 students (13–18 years) from the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys conducted in 4 urban school districts. Respondents were 51% Hispanic/Latino, 21% black/African-American, 14% white. Generalized additive models were used to examine the functional form of relationships between self-reported gender expression (range: 1=Most gender conforming, 7=Most gender nonconforming) and 5 indicators of violence and bullying victimization. We estimated predicted probabilities across gender expression by sex, adjusting for sexual orientation identity and potential confounders.

RESULTS

Statistically significant quadratic associations indicated that girls and boys at the most gender conforming and nonconforming ends of the scale had elevated probabilities of fighting and fighting-related injury, compared to those in the middle of the scale (p < .05). There was a significant linear relationship between gender expression and bullying victimization; every unit increase in gender nonconformity was associated with 15% greater odds of experiencing bullying (p < .0001).

CONCLUSIONS

School-based victimization is associated with conformity and nonconformity to gender norms. School violence prevention programs should include gender diversity education.

Keywords: bullying, child & adolescent health, public health, stress, violence, special populations

There has been heightened attention to bullying and violence victimization in US schools, particularly for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth.1–5 Less is known about bullying and violence directed at adolescents who do not conform to societal expectations for masculine or feminine appearance and behavior (that is, have a nonconforming gender expression). Some research suggests that youths with a nonconforming gender expression are also at high risk of bullying victimization, discrimination, and violence.2,6,7 A 2013 national convenience sample of LGBT high school students found that 55% of respondents had been verbally harassed and 11% had been physically assaulted at school due to their gender expression.2 However, data from heterogeneous population-based samples of youth are lacking.

There is a particular need to understand links between victimization and perceived gender expression for youth of all sexual orientation identities. Evidence indicates that sexual minority youth are more likely to be gender nonconforming.8–10 Yet, gender expression is distinct from sexual orientation identity and many heterosexual youth also report gender nonconformity.11,12 Thus, to increase our understanding of the stigma-related factors that contribute to adolescent experiences of bullying and violence, it is essential to investigate the relationship between gender expression and victimization, and its potential implications for adolescent health, independently of sexual orientation identity. Indeed, violence and bullying victimization toward those perceived as gender nonconforming have been associated with adverse mental and physical health outcomes, including depression and suicidality, not only among sexual minorities13 but across all sexual orientation identities, including heterosexuals.12,14

In addition to a need for research on gender expression and victimization for those of all sexual orientation identities, few studies have been able to examine violence and bullying victimization across the full range of gender expression (from highly gender conforming to highly gender nonconforming). The relationship between having a highly conforming gender expression and violence or bullying is especially poorly understood, although there is evidence that pressures to conform to gender norms may also impact health risks for more gender conforming adolescents. For example, men who report greater conformity to masculinity norms are more likely to engage in risk-taking, including high-risk alcohol use and more frequent tobacco use,15–17 and to have engaged in intimate partner violence.18 Few studies have quantified relationships between conformity to femininity norms and risk-taking or violence exposure, although qualitative research has linked conventional feminine gender ideologies in girls and women to increased tolerance of sexual risk behavior and risk of intimate partner violence.19,20

Leveraging data from the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System on gender expression in school contexts, this study sought to address these gaps by examining the association between self-reported gender expression and school-based victimization within ethnically diverse probability samples of public high school students from 4 urban locations.

METHODS

Participants

The current study used 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data from 4 jurisdictions that included a novel measure of perceived gender expression (described below): Broward County, FL; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA; and San Diego, CA (N = 6000). Each survey used a 2-stage cluster sample design to produce a representative sample of 9th through 12th grade students.21 The surveys were conducted following local parental permission procedures. Due to small sample size, participants who were 12 years of age were excluded. Individuals missing responses on key variables were excluded from the analysis (gender expression, 4.9%; sex, <1%; key covariates, 3.1%). In addition, respondents missing information on each outcome were excluded from outcome-specific analyses. Final unweighted analytic samples ranged from N = 5412 to N = 5469.

Measures

Sex

Respondents were asked “What is your sex?” with response options male or female. No jurisdiction included a question on gender identity or other items that would permit identification of transgender respondents.

Gender expression (GE)

Perceived GE was assessed with a self-report question, based on a 2-item measure developed for adolescents22 and adapted and tested for use in YRBS questionnaires by making it specific to school contexts.23 This item purposefully solicits self-reported perceptions, given the central role that such perceptions play in stigmatization processes.22,24 Respondents were asked: “A person’s appearance, style, dress, or the way they walk or talk may affect how people describe them. How do you think other people at school would describe you?” with response options ranging on a seven-point scale from “very feminine” to “very masculine.” Responses were recoded based on respondent sex to create a continuous variable indicating degree of conformity or nonconformity to societal norms of GE (range: 1 = most gender conforming, 7 = most gender nonconforming).

School-based violence and bullying victimization

In the jurisdictions in this study, 6 items assessed violence and bullying victimization. Three items asked about experiences of physical violence in the past year (“How many times were you in a physical fight on school property?” “How many times has someone threatened or injured you with a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property?” “How many times were you in a physical fight in which you were injured and had to be treated by a doctor or nurse?”), with 5 to 8 response options. One item asked about perceived safety (“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school because you felt you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school?”). Each outcome was dichotomized (0 = no occurrence, 1 = at least one occurrence). Two dichotomous items asked about bullying victimization in the past year: “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property?” and “During the past 12 months, have you ever been electronically bullied?” The distribution of these 2 items was similar across GE, and thus, the items were combined into a single indicator of any past year bullying victimization (in-school or electronic; 0 = no, 1 = yes).

Sexual orientation identity and other demographic characteristics

Sexual orientation identity was assessed with the question: “Which of the following best describes you?” (heterosexual (straight), gay or lesbian, bisexual, not sure). Race/ethnicity was assessed using two survey questions: “Are you Hispanic or Latino?” (yes or no) and “What is your race?” (select all that apply). Responses were classified as Hispanic/Latino, black/African-American, white, Asian/Pacific Islander, and another race/multiracial. Age was assessed via self-report in years.

Data Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses and hypothesis testing using SAS version 9.3 procedures designed to account for the complex sampling design and survey weights (eg, PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC).25 Following descriptive analyses, we used generalized additive models (GAMs; SAS PROC GAM) to examine the functional form (that is, function that describes the shape of the relationship between variables) of the associations between GE score and the proportion reporting each outcome. GAMs help in examining potential non-linear associations by relaxing assumptions of linearity and generating smoothed curves of association with 95% confidence intervals.26 Based on patterns observed in GAMs, we used logistic regression models including linear, quadratic, and cubic polynomial functions of GE as predictors of the odds of reporting each form of victimization, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation identity. Sex-by-GE and sexual orientation identity-by-GE interactions were included to examine whether sex or sexual orientation identity, respectively, modified the associations between GE and each outcome. Finally, the predicted probability of endorsing each outcome across the GE spectrum was calculated as the inverse logit of the model-based estimate; probabilities were calculated at the average sample age (16.1 years), weighting the racial/ethnic and sexual orientation identity variables by their marginal distributions.

RESULTS

The analytic sample included 2921 girls and 2548 boys in high school who participated in a 2013 YRBS in one of the 4 included jurisdictions. Weighted socio-demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in the first column of Table 1. Table 1 also presents the weighted distributions of each of the five violence and bullying victimization outcomes by sociodemographic characteristics and by GE.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Reported School-related Violence and Bullying Victimization among 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Respondents (ages 13–18 years) from 4 Urban School Districtsa

| Total, % | In 1+ physical fights (past yr.) |

Threat/injury w. weapon (past yr.) |

Injured in fight, needed trt. (past yr.) |

Missed school because felt unsafe (past mo.) |

Any bullying vict. (past yr.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % (N) | (N=5412) % | (N=5448) % | (N=5437) % | (N=5424) % | (N=5469) % | |

| Overall | 100 (5469) | 8.8 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 7.7 | 17.9 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 50.5 (2921) | 6.5 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 8.2 | 20.7 |

| Male | 49.5 (2548) | 11.1 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 7.1 | 15.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 55.9 (2793) | 8.2 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 17.6 |

| Black/African American | 21.0 (1076) | 13.7 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 9.6 | 15.5 |

| White | 13.5 (812) | 4.6 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 7.5 | 21.8 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6.4 (504) | 6.2 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 19.6 |

| Multi/Another | 3.2 (284) | 9.6 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 18.3 |

| Sexual orientation identity | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 88.6 (4855) | 8.2 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 6.9 | 15.8 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.9 (104) | 20.4 | 19.8 | 10.9 | 21.8 | 29.7 |

| Bisexual | 5.6 (302) | 14.8 | 8.3 | 6.3 | 10.7 | 34.0 |

| Not Sure | 3.9 (208) | 8.8 | 9.6 | 7.4 | 13.1 | 35.1 |

| Gender expression scoreb | ||||||

| 1 | 33.7 (1816) | 9.9 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 7.0 | 14.7 |

| 2 | 32.5 (1866) | 6.1 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 5.4 | 15.6 |

| 3 | 14.9 (802) | 7.3 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 20.6 |

| 4 | 10.3 (564) | 8.0 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 8.5 | 25.2 |

| 5 | 3.0 (164) | 13.9 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 13.6 | 26.2 |

| 6 | 1.8 (96) | 14.3 | 16.1 | 6.2 | 14.2 | 21.7 |

| 7 | 3.8 (161) | 24.4 | 16.0 | 12.5 | 21.6 | 26.2 |

Note.

For all demographic variables and outcomes % is weighted; n is unweighted

Broward Co., FL; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA; San Diego, CA

Gender expression score range: 1 = Most gender conforming; 7 = Most gender nonconforming

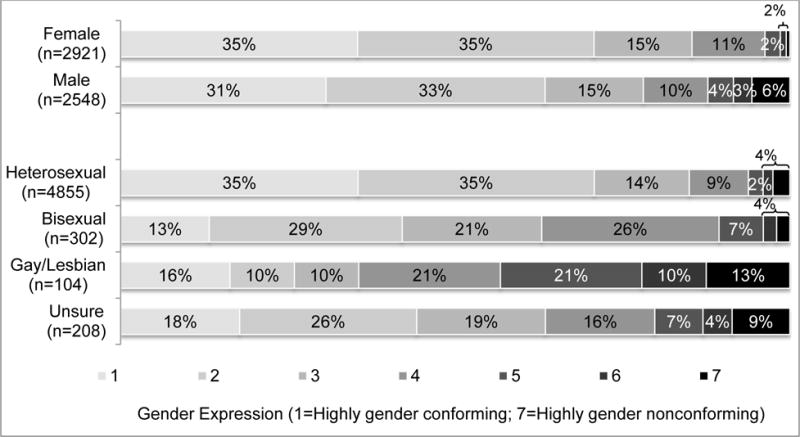

Figure 1 depicts the weighted distribution of GE across sex and sexual orientation identity in this sample. A higher proportion of male than female participants were located at the most gender nonconforming end of the spectrum (for example, 6% vs. 1%, respectively, for those with a GE score = 7). Greater gender nonconformity was also associated with sexual minority identities: there were higher proportions of those identifying as gay/lesbian (13%) or unsure (9%) than those identifying as heterosexual (3%) at the most nonconforming end of the spectrum. Conversely, a higher proportion of heterosexual respondents (35%) than sexual minority respondents (16% for gay/lesbian, 13% for bisexual, and 18% for unsure) located themselves at the most gender conforming end of the spectrum (GE score = 1).

Figure 1.

Gender Expression among High School Students by Sex and Sexual Orientation Identity in 4 Urban School Districts (2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys; N = 5469)

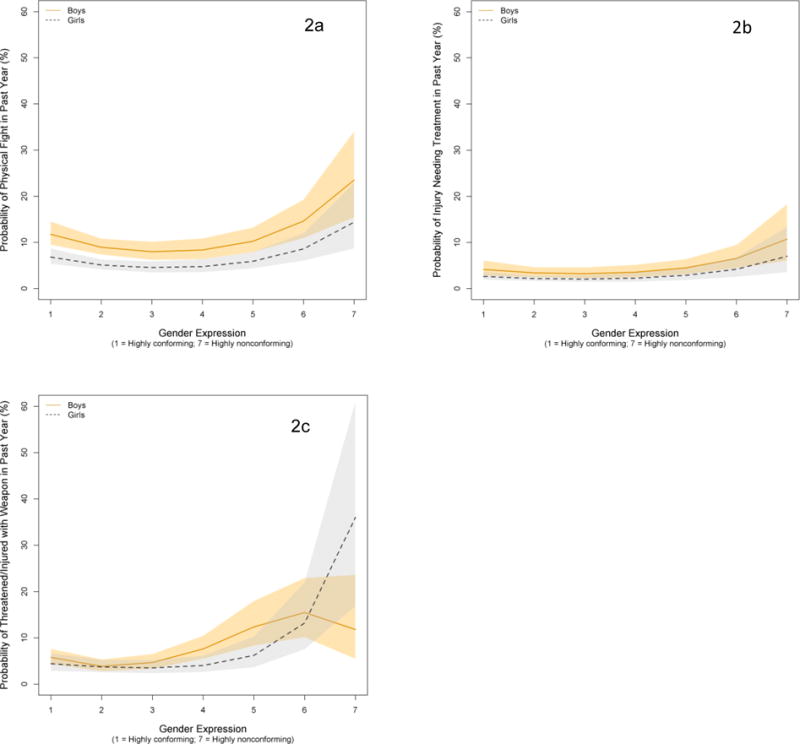

GAM analyses and subsequent multivariable logistic models demonstrated statistically significant quadratic associations between GE and fighting and fight-related injury needing treatment, for both boys and girls (Figures 2a, 2b). Notably, sex was significantly associated with both outcomes, with boys having a higher probability of fighting (p < .001) and of injury in a fight (p = .006) across all levels of GE; no sex-by-GE interactions were observed for these outcomes. The J-shaped relationship between GE and fighting, in particular, suggests that the most gender conforming and the most gender nonconforming respondents had an elevated risk of fighting, relative to respondents in the middle of the GE spectrum (Figure 2a). For example, the adjusted predicted probability (95% confidence interval) of having been in at least one fight was 6.8% (5.3%, 8.7%) for girls and 11.8% (9.4%, 13.5%) for boys at the most gender conforming end of the scale (GE = 1) compared to their more moderately conforming peers (GE = 2: 5.1% [4.1%, 6.3%] for girls and 8.9% [7.4%, 10.8%] for boys). At the most nonconforming end of the GE range (GE = 7), the probability of having been in a fight was 14.4% (8.7%, 22.9%) for girls and 23.5% (15.4%, 34.1%) for boys.

Figure 2. Predicted Probabilities of Fighting or Violence Victimization in School Settings by Perceived Gender Expression and Sex among High School Students in 4 Urban School Districts (2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys; N = 5469).

Note.

Graphs show predicted probabilities separately by sex (girls=dashed line; boys=solid line). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals around predicted probabilities. All models account for clustering by school district, are weighted to account for sampling design, and are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation identity. Models: (2a) probability of having been in a physical fight in past year; (2b) probability of injury in a physical fight, needing treatment by a doctor or nurse in the past year; and (2c) probability of having been threatened or injured with a weapon in the past year. In all models, a main effect of sex was observed; in Model 2c, there was also a significant interaction between sex and gender expression. There were no significant interactions between sexual orientation identity and gender expression.

There was a significant sex-by-GE interaction when modeling the risk of being threatened or injured with a weapon (interaction p-values < .05). GAM analyses suggested a significant quadratic relationship between GE and this outcome for girls and a significant cubic relationship between GE and this outcome for boys (Figure 2c). Among girls, the quadratic model indicated a pronounced elevated probability of victimization with a weapon for the most gender nonconforming girls (36% predicted probability for the most nonconforming girls compared to 4% for those in mid-range of GE). Among boys, the cubic model indicated increased probability of victimization with a weapon for boys at the most conforming end of the range (5.7% if GE = 1 compared to 3.9% if GE = 2), and an overall elevated probability among the nonconforming boys, tapering off for the most nonconforming (15.5% if GE = 6, 11.8% if GE = 7).

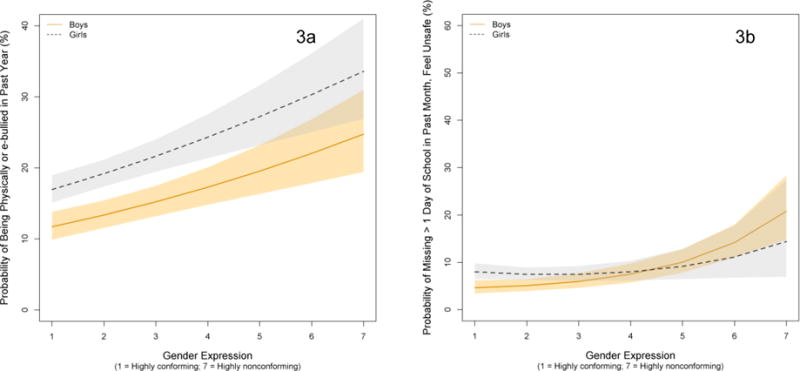

In contrast to the above outcomes, a linear relationship best fit the association between GE and bullying victimization and missing school due to feeling unsafe (Figures 3a, 3b). Greater gender nonconformity was significantly associated with higher odds of having experienced in-school or electronic bullying victimization in the past year or having missed school for safety reasons in the past month (both p < .001). Girls had a higher probability of being bullied across all levels of GE (p < .001). Sex-by-GE interaction terms were only significant for missing school (p < .001): the most gender conforming boys were less likely, while the most nonconforming boys were more likely, than girls to have missed school for safety reasons. There were no significant interactions between sexual orientation identity and GE for any outcome; thus, these interaction terms were not included in final models.

Figure 3. Predicted Probabilities of Bullying or Missing School for Safety Reasons by Perceived Gender Expression and Sex (girls=dashed line; boys=solid line) among High School Students in 4 Urban School Districts (2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys; N = 5469).

Note.

Graphs show predicted probabilities separately by sex (girls=dashed line; boys=solid line). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals around predicted probabilities. All models account for clustering by school district, are weighted to account for sampling design, and are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation identity. Models: (3a) probability of experiencing at-school or electronic bullying victimization in past year; and (3b) probability of having missed school 1+ days in past month due to feeling unsafe. In all models, a main effect of sex was observed; additionally, in Model 3b, there was a significant interaction between sex and gender expression. There were no significant interactions between sexual orientation identity and gender expression.

DISCUSSION

In probability samples of public high school students from four urban locations, the odds of being targeted for bullying and violence were found to significantly differ by gender expression, after adjusting for the effects of sexual orientation identity. The J-shaped relationships for violence-related outcomes suggest increased risk for youths who are perceived by others at school as highly gender conforming as well as those perceived as highly gender nonconforming. In contrast, there was a linear relationship between gender nonconformity and odds of in-school or electronic bullying or missing school due to feeling unsafe.

These findings expand the existing literature on gender nonconformity and violence and discrimination among adolescents. Previously, most of this research has focused on sexual minorities.2,6,7,13 We found associations between gender nonconformity and violence and bullying even after accounting for sexual orientation identity. Further, sexual minorities were more likely to report a nonconforming gender expression; however, the majority of respondents at the gender nonconforming end of the scale were heterosexual, underscoring the importance of these issues for both heterosexual and sexual minority youth. These findings add support to prior studies conducted in a predominantly white, middle-income cohort that demonstrated increased risk of childhood abuse and bullying victimization among gender nonconforming heterosexual and sexual minority young people.12,14 Our findings indicate similar associations in an ethnically diverse adolescent sample. Although sample size limitations precluded an examination of differences by race/ethnicity in this analysis, future research is needed that explores these intersections.

We also observed modestly elevated odds of fighting, injury needing treatment, and missing school due to feeling unsafe for boys and girls reporting the highest levels of gender conformity. For the boys in the sample, this aligns with a robust body of work describing male conformity to masculinity norms as a predictor of aggression, violence perpetration, and violence victimization among men.27–30 Conformity to masculinity norms in adolescence and young adulthood has also been associated with heavier alcohol use,15,31 which raises risk of experiencing or perpetrating violence.32,33 One study even found differences in injury-risk behaviors associated with conformity to masculinity norms in children as young as 3–6 years old.34 However, few studies have specifically examined the experience of adolescents who report that they are perceived as having a highly conforming gender expression, which may be distinct from an individual’s adherence to conventional masculine and/or feminine ideologies.

In this study, there was some suggestion that the violence-related risks of highly gender conforming girls followed a pattern similar to that of the boys in the sample. Literature on violence and female conformity to femininity norms has largely focused on sexual and romantic relationships, including sexual risks and intimate partner violence.19,36 There is much still to be understood about the relationship between high degrees of gender conformity and violence perpetration as well as victimization, particularly given that perpetrators may also be victims of bullying and discrimination.37,38 The factors underlying the related but distinct outcomes examined may vary by gender in ways that are beyond the scope of this study. For example, highly gender conforming girls may be experiencing elevated levels of sexual harassment compared to girls in the middle of the spectrum, which may lead some to miss school due to feeling unsafe. Elevated odds of having been in a physical fight may be related to fighting back in response to harassment, may indicate exposure to intimate partner violence,39 or may be related to other forms of social group conflict.35 For example, Brown and Tappan35 described shifting femininity ideologies among US middle school age girls in conjunction with a rise in media images of teenage girls in physical fights, which could also have implications for the links between perceived gender conformity and physical fighting in girls.

Sex-by-gender expression interactions were found for two outcomes: having being threatened or injured with a weapon and having missed school due to feeling unsafe. For the outcome of threat or injury with a weapon, the cubic effect among boys was distinct from all other observed patterns, and the elevated risk among girls at the most nonconforming end of the spectrum was substantially higher than for all other outcomes except bullying. This differing shape may be driven by relatively sparse data for this outcome but also could be related to differences in the social environments and social experiences of boys and girls who reported being at the most nonconforming end of the scale compared to those who were slightly less nonconforming. These differences might reflect community-level differences in availability of guns, school violence policies, or local drug-related or law enforcement activity. Although this study adjusted for clustering by region and school, there may be other factors related to sex and perceived gender expression that remained unmeasured.

Overall, the prevalence of violence and bullying victimization in this four school district sample was similar to levels reported on the 2013 national YRBS, with the exception of physical fighting, which was reported by 9% of our sample compared to 25% of respondents nationwide.36 The lower prevalence of physical fighting in our sample is notable, and may suggest key differences between the districts in this sample and the US in general that could have implications for reducing exposure to violence and should be examined in future research.

We note several limitations to this study. First, all measures are self-reported and there may be additional factors we could not account for that might lead some students to report higher levels of gender conformity or nonconformity, including factors also linked to violence or bullying victimization (such as characteristics of perpetrators). Further, gender expression is multidimensional, and our measure represents only one approach to the measurement of perceived masculine and feminine expression; although survey research requires brief, validated measures such as this one, alternate strategies for assessing gender expression at the population level should be explored in future research. In addition, the YRBS questionnaires did not include measures allowing for the identification of transgender youth, a group that may be heavily impacted by gender expression-related discrimination. Efforts have already begun—and should be expanded—to promote visibility of transgender youth on population-based surveys such as the YRBS.37,38

Second, as a cross-sectional study, temporal ordering of these relationships cannot be determined. There is robust evidence that gender nonconformity may be targeted by peers for discrimination and victimization,2,6,14 but there is also the possibility that prior victimization experiences may impact reported or actual gender expression. In a study of 5th graders, peer victimization in the fall term predicted decreased engagement in gender nonconforming behaviors in the spring for boys, while among girls, victimization predicted decreased engagement in both conforming and nonconforming activities.39 Longitudinal research is necessary to disentangle these relationships. Third, generalizability is limited as this sample comes from four urban school districts that were motivated to include a novel measure of gender expression. Yet, even in these jurisdictions that may already have been more attuned to issues of gender diversity in their student body, greater gender nonconformity was strongly associated with elevated odds of victimization, suggesting that these may be underestimates of the experiences of youth nationwide. Future uptake of this item by additional jurisdictions or as part of the national YRBS will allow for greater generalizability to the US high school student population, and will also permit needed examination of gender expression differences by race/ethnicity and geographic area.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use a geographically diverse population-based sample to better understand experiences related to gender expression, bullying, and violence in school contexts for 9th through 12th grade students. Based on these findings, schools should consider the following in efforts to address and prevent bullying and violence:

Both girls and boys who are more gender nonconforming may be at elevated risk of violence and bullying victimization in school settings;

These preventable experiences of stigmatization and discrimination based on gender expression impact not only LGBT students, but students of all sexual orientation identities;

Given our finding that highly gender conforming youth may be at elevated risk of fighting and victimization, school-based violence prevention programs should incorporate curriculum celebrating gender diversity and identifying the negative effects of gender stereotypes across a full spectrum of gender expression.

In our study’s probability sample, which was predominantly youth of color, findings emphasize the need for future research focused on the intersections of gender expression, racial/ethnic background, and sexual orientation identity. This will have additional implications for the development and implementation of effective anti-violence and anti-bullying initiatives that address the interplay of multiple forms and multiple levels of stigma and discrimination in school contexts (from state- and district-level policies pertaining to gender and sexual diversity to individual experiences of bullying or violence at school). Inclusion of gender expression norms and gender diversity in relation to other social determinants of health within school violence prevention efforts may offer new insights and pathways toward promoting school health and mitigating the social stressors that drive health inequities.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board determined that protocol approval was not necessary because the study used de-identified data from secondary sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey participants and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the data used in this study. AR Gordon is supported by NIH F32DA042505. JP Calzo is supported by NIH K01DA034753. SB Austin is supported by NIH R01 HD066963 and R01 HD057368 and by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services (T71-MC00009; T76-MC00001). The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Allegra R. Gordon, Fellow, Division of Adolescent & Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Avenue (AU-Box 17, BCH 3189), Boston, MA 02115.

Kerith J. Conron, Blachford-Cooper Distinguished Scholar and Research Director, The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1476.

Jerel P. Calzo, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Public Health, Core Investigator, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182-4162.

Matthew T. White, Statistician – Department of Clinical Research Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115.

Sari L. Reisner, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115.

S. Bryn Austin, Professor, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Professor, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115.

References

- 1.Birkett M, Russell ST, Corliss HL. Sexual-orientation disparities in school: the mediational role of indicators of victimization in achievement and truancy because of feeling unsafe. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1124–1128. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, Boesen MJ. The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. New York, NY: GLSEN; 2014. Available at: http://www.glsen.org/article/2013-national-school-climate-survey. Accessed April 19, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller AS, James W, Abrutyn S, Levin ML. Suicide ideation and bullying among us adolescents: examining the intersections of sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):980–985. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell ST, Ryan C, Toomey RB, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: implications for young adult health and adjustment. J Sch Health. 2011;81(5):223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon AR, Meyer IH. Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against LGB individuals. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3(3):55–71. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(6):1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieger G, Linsenmeier JAW, Gygax L, Bailey JM. Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):46–58. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rieger G, Savin-Williams RC. Gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, and psychological well-being. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(3):611–621. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey JM, Zucker KJ. Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation: a conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Dev Psychol. 1995;31(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plöderl M, Fartacek R. Childhood gender nonconformity and harassment as predictors of suicidality among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual Austrians. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;38(3):400–410. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity: a risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):410–417. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, Korr WS, Sites EW. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(5):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: an 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee CS, Takamatsu S, Gordon D. “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: the role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addict Behav. 2011;36(9):906–911. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR. The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):142–152. doi: 10.1037/a0022917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtenay WH. Engendering health: a social constructionist examination of men’s health beliefs and behaviors. Psychol Men Masc. 2000;1(1):4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Sexuality and the limits of agency among South African teenage women: theorising femininities and their connections to HIV risk practises. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(11):1729–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerrigan D, Andrinopoulos K, Johnson R, Parham P, Thomas T, Ellen JM. Staying strong: gender ideologies among African-American adolescents and the implications for HIV/STI prevention. J Sex Res. 2007;44(2):172–180. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system — 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wylie S, Corliss HL, Boulanger V, Prokop LA, Austin SB. Socially assigned gender nonconformity: a brief measure for use in surveillance and investigation of health disparities. Sex Roles. 2010 May; doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9798-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greytak EA, Gill A, Conron KJ, et al. Identifying transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys: special considerations for adolescents, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and intersex status. In: Herman JL, editor. Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population- based Surveys. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2014. pp. 29–43. Available at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAS Institute Inc. SAS Software, Version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized Additive Models. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong L. Toward a transformed approach to prevention: breaking the link between masculinity and violence. J Am Coll Health. 2000;48(6):269–279. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychol Men Masc. 2005;6(1):46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz J. Reconstructing masculinity in the locker room: the Mentors in Violence Prevention Project. Harv Educ Rev. 1995;65(2):163–175. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, et al. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychol Men Masc. 2003;4(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahalik JR, Burns SM. Predicting health behaviors in young men that put them at risk for heart disease. Psychol Men Masc. 2011;12(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells S, Flynn A, Tremblay PF, Dumas T, Miller P, Graham K. Linking masculinity to negative drinking consequences: the mediating roles of heavy episodic drinking and alcohol expectancies. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(3):510–519. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisco CG, Leone RM, Gallagher KE, Parrott DJ. “Demonstrating masculinity” via intimate partner aggression: the moderating effect of heavy episodic drinking. Sex Roles. 2015;73(1):73–71. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0500-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granié M-A. Gender stereotype conformity and age as determinants of preschoolers’ injury-risk behaviors. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42(2):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown LM, Tappan MB. Fighting like a girl fighting like a guy: gender identity, ideology, and girls at early adolescence. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2008;(120):47–59. doi: 10.1002/cd.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Suveillance – United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Federal Interagency Working Group on Improving Measurement of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Federal Surveys. Toward a Research Agenda for Measuring Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Federal Surveys: Findings, Recommendations, and Next Steps. Washington, DC: Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology; 2016. Available at: https://fcsm.sites.usa.gov/files/2014/04/SOGI_Research_Agenda_Final_Report_20161020.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.The GenIUSS Group. Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2014. Available at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ewing Lee EA, Troop-Gordon W. Peer socialization of masculinity and femininity: differential effects of overt and relational forms of peer victimization. Br J Dev Psychol. 2011;29(Pt 2):197–213. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2010.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]