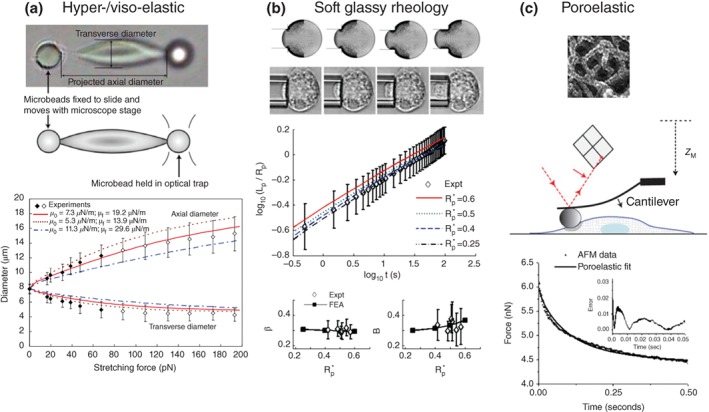

Figure 2.

Examples of experimental measurements and mechanical models of bulk mechanical properties of cells. (a) Mills et al.51 used optical tweezers to perform uniaxial extension and relaxation experiments on red blood cell to parameterize hyperelastic and viscoelastic constitutive equations of its mechanical behavior (Reprinted with permission from Ref 51. Copyright 2004 Tech Science Press); (b) Zhou et al.45 implemented a finite element model (top image in (b)) with a power‐law rheology based constitutive equation to capture the long‐time‐range soft‐glassy like response of cells as measured by creep tests using micropipette aspiration (middle of panel) (Reprinted with permission from Ref 45. Copyright 2012 Springer); (c) Herant and Dembo18 used the poroelastic continuum mechanics equations to account for the porous nature of the cytoskeletal network (image shown in the top panel of (c), reprinted with permission from Ref 18. Copyright 2010, Elsevier Inc.) and the movement of fluid through these pores. The influence of fluid reorganization during mechanical perturbations and the poroelastic nature of the cell have been recently experimentally measured (and fitted with a poroelasitc model) by Moeenderbary et al. 22 (middle and bottom panels, reprinted with permission from Ref 22. Copyright 2013 Nature Publishing Group).