Abstract

The magnetic actuation of deposited drops has mainly relied on volume forces exerted on the liquid to be transported, which is poorly efficient with conventional diamagnetic liquids such as water and oil, unless magnetosensitive particles are added. Herein, we describe a new and additive‐free way to magnetically control the motion of discrete liquid entities. Our strategy consists of using a paramagnetic liquid as a deformable substrate to direct, using a magnet, the motion of various floating liquid entities, ranging from naked drops to liquid marbles. A broad variety of liquids, including diamagnetic (water, oil) and nonmagnetic ones, can be efficiently transported using the moderate magnetic field (ca. 50 mT) produced by a small permanent magnet. Complex trajectories can be achieved in a reliable manner and multiplexing potential is demonstrated through on‐demand drop fusion. Our paramagnetofluidic method advantageously works without any complex equipment or electric power, in phase with the necessary development of robust and low‐cost analytical and diagnostic fluidic devices.

Keywords: drops, liquid marbles, liquid transport, magnetic control, microfluidics

Controlling the motion of drops on surfaces is the cornerstone of a broad range of scientific and technological operations.1, 2 In the large majority of cases, the drop motion is induced by an interfacial energy gradient at a solid/liquid interface (wettability gradient) and/or at a free interface (Marangoni stress).3 This has resulted in a plethora of studies to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms that convert such gradients into drop motion4 as well as to develop strategies to manipulate drops under the control of various external signals, such as thermal,5 electrical2, 6, 7 and optical8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 stimuli. Most of these approaches necessitate the implementation of rather complex components, such as electrodes or optical elements, or the development of systems that are intrinsically responsive to the desired stimulus, such as photo‐ or thermosensitive substrates.8, 9 This has led to the emergence of a broad variety of powerful drop actuation strategies that work in a laboratory environment, that is, require specific equipment and well‐controlled conditions (for example, protection from ambient light or precise control of temperature and surface tension). However, broadly applicable strategies for robust and cost‐effective manipulation of discrete liquid entities have yet to be identified. Apart from thermal, optical, and electrical stimulation, magnetic field‐induced drop actuation could be the basis to achieve such a goal.14, 15 In particular, permanent magnets are available in a variety of sizes and shapes at affordable prices and can be easily handled without any specific environmental requirement. However, although drops composed of strongly responsive fluids, such as paramagnetic liquids16, 17 or ferrofluids,18, 19, 20 are commonly actuated by magnets, the majority of conventional drops are made of diamagnetic liquids (for example, water and oil) and cannot be efficiently manipulated unless a strong magnetic field is applied. To our knowledge, the only strategy for moving discrete diamagnetic liquid entities in air using moderate magnetic fields has consisted in using magnetosensitive particles, dispersed inside the liquid21 or coating the liquid to form liquid marbles.14, 22, 23, 24, 25 Using magnetic particles inside or outside the liquid increases sample cost, reduces applicability, and poses the problem of sample contamination. Moreover, although liquid marbles allow efficient liquid transport,26, 27 they remain, unlike their drop counterparts, difficult to merge and split apart for digital fluidic operations.2 Herein, we propose a new way to move and merge any kind of discrete liquid entity, including diamagnetic and nonmagnetic ones, using external small permanent magnets. Our method does not require the use of any magnetosensitive particles, nor has it any specific restrictions in terms of environmental conditions. It consists in using a paramagnetic liquid as a substrate and exploits the deformation induced by an approaching magnet as the driving force for a floating entity. To our knowledge, although the magnetic field‐induced deformation of a paramagnetic liquid is a well‐known phenomenon that has been used in various scientific fields,28, 29 it has never been exploited to transport guest liquid entities. We characterized the deformation induced by small permanent magnets and analyzed the resulting motion of different floating entities, including oil drops and water‐based liquid marbles of various compositions. We also experimentally and theoretically quantified the marked contribution of the substrate deformation to the motion of a floating object under magnetic stimulation. We finally used mobile magnets to perform various operations such as long‐term transport along complex trajectories and magnetically controlled drop fusion.

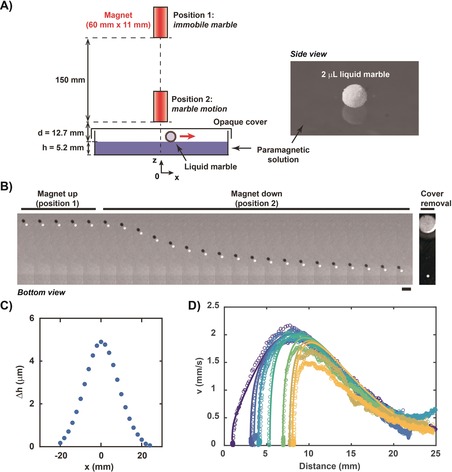

Our experimental set‐up consisted of a Petri dish containing a paramagnetic HoCl3 solution used as a deformable substrate. The liquid thickness (5.2 mm) was fixed at a value larger than the capillary length of the system (ca. 2.7 mm). A portable, permanent NdFeB magnet was released from a fixed position far from the substrate surface to follow a free fall trajectory and reach a second fixed position close to the substrate surface (12.7 mm), resulting in motion of floating objects deposited on the substrate. We first used a 2 μL liquid marble (LM), made of hydrophobically modified silica nanoparticles surrounding a water core,27 as the entity to be transported (Figure 1 A). With the magnet maintained in position 1, no marble motion was detected. Switching the magnet from position 1 to 2 led to an immediate and radial motion of the marble away from the magnet axis (Figure 1 B and the Supporting Information, Movie S1). To our knowledge, this is the first reported magnetically induced motion of a liquid marble that does not contain any ferromagnetic or paramagnetic component (in the coating particles or in the inner core). A key component of this motion is the deformation of the substrate resulting from the applied magnetic field (Supporting Information, Figure S1). When the magnet was switched from position 1 to position 2, the surface was elevated toward the magnet forming a stationary radially symmetric bump with a maximum height of about 5 μm and a radial extent of about 20 mm (Figure 1 C), thus creating a slope onto which the marble could slide.27 Regardless of the initial distance between the LM and the magnet axis, the LM first rapidly accelerated up to a maximal speed v max≈2 mm s−1 and then slowly decelerated (Figure 1 D, symbols). This maximal speed could be increased by simply bringing the magnet closer to the substrate. For instance, decreasing the magnet‐to‐substrate distance in position 2 from 12.7 mm to 9.8 mm led to v max≈4.8 mm s−1 (Supporting Information, Figure S2 and Movie S2).

Figure 1.

Magnetic actuation of a water liquid marble on a paramagnetic liquid substrate. A) Experimental set‐up with a 2 μL water liquid marble (diameter 1.6 mm) floating on a paramagnetic solution ([HoCl3]=100 mm) in a closed Petri dish. The free‐fall switch of a permanent magnet from position 1 (far from the substrate surface) to position 2 (close to the substrate surface) induces marble motion. B) Kymograph of the marble (bottom view) upon switching the magnet from position 1 (up) to position 2 (down). The white and black disks are the marble and its shadow, respectively. Frames are separated by 2 s. Scale bar=5 mm. The last image on the right indicates the position of the magnet that can be seen once the cover has been removed. The corresponding video is provided as Movie S1. C) Radial elevation of the substrate surface, Δh, when the magnet is switched from position 1 to position 2. Error bars are smaller than the symbol size. D) Speed of the liquid marble as a function of the distance to the central axis of the magnet. Each curve corresponds to a different initial position. Symbols are experimental data and solid lines are theoretical curves calculated using the experimental measurements of both magnetic field profile and surface deformation and the same value of C for all curves (Supporting Information, Section S1).

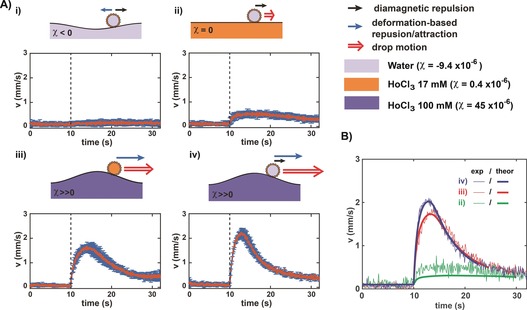

We hypothesized that the two main components leading to marble motion were the diamagnetic repulsion exerted on the marble and the deformation‐induced gravity force, both of which induced a repulsion of the marble from the magnet axis. To quantify the relative contribution of each component, we varied the magnetic susceptibility (χ) of the liquid marble as well as that of the substrate (Figure 2), by using HoCl3 solutions of different concentrations (Supporting Information, Figure S3). We first used a water LM on a water substrate (χ=−9.5±0.4×10−6 for both the LM and the substrate). No significant motion could be detected, which was attributed to the attractive contribution of the surface deformation (depression) counteracting the diamagnetic repulsion (Figure 2 A, i). The effect of the diamagnetic repulsion only on the water LM was assessed by using a 17 mm HoCl3 solution as the substrate (χ=0.4±0.1×10−6), so that no surface deformation occurred (Figure 2 A, ii). The LM then moved at a relatively low speed (v max=0.6±0.1 mm s−1). In contrast, a much higher speed (v max=1.7±0.2 mm s−1) was obtained when a 17 mm HoCl3 LM was used on a 100 mm HoCl3 substrate (χ=45±1.7×10−6), that is, in the case of a motion induced by the substrate deformation only (Figure 2 A, iii). When the water LM was placed on this substrate (same conditions as in Figure 1), the strongest response to the magnet was obtained (v max=2.2±0.2 mm s−1) as a result of the additive contributions of both the diamagnetic repulsion and the substrate deformation (Figure 2 A, iv). We built an analytical model (Supporting Information, Section S1) for the LM motion including weight, buoyancy, surface tension, drag force, and magnetic repulsion exerted on the LM floating on the liquid substrate, which led to Equation (1):

| (1) |

Figure 2.

The motion is mainly driven by substrate deformation. A) Scheme of the main components of marble motion and speed as a function of time for a 2 μL liquid marble made of water (i, ii, and iv, χ<0) or 17 mm HoCl3 (iii, χ≈0) on a water substrate containing different amounts of HoCl3: 0 mm (i, χ<0); 17 mm (ii, χ≈0); and 100 mm (iii and iv, χ≫0, bottom). The marble motion (double red arrow) results from the combination of the diamagnetic repulsion (black arrow) and the substrate deformation‐driven gravity force (blue arrow). Each graph shows the experimental speed data (mean±sd for 6 independent experiments) with an initial distance between the marble and the magnet axis within the range of 0–5 mm. The dashed line indicates the time at which the magnet was switched from position 1 to 2. B) Three sets of experimental data (thin lines) taken in the three configurations in which marble motion was observed (ii, iii, and iv) and corresponding theoretical curves (thick lines) calculated with the same value of C as in Figure 1, using the experimental measurements of both magnetic field profile and surface deformation (Supplementary Information, Section S1).

where and and χ, , , , and are the magnetic susceptibility, velocity, mass, radius, volume, and wrapping angle of the LM, respectively (Supporting Information, Scheme S1), and is the local elevation of the substrate, is the vacuum permeability, and C is a numerical prefactor of the drag force (on the order of 130). was determined according to Ooi et al.31 and found to be around 14°. Equation (1) was integrated numerically using the experimentally determined values for both and . The only unknown parameter, C, was determined by fitting the data for the water LM on a 100 mm HoCl3 substrate and was kept constant for all other conditions. The resulting calculated curves reproduced particularly well the experimental data, even in the absence of any adjustable parameter (Figure 2 B), showing that the marble motion is essentially a combination of substrate deformation‐induced and diamagnetic repulsions. Our model thus confirmed the experimental observation that the main contribution to the motion of a marble floating on a paramagnetic substrate was the magnetically induced substrate deformation and not the magnetic effect on the marble itself. Our method thus constitutes a new way to efficiently transport floating objects, even diamagnetic (for example, water) or non‐magnetic (for example, 17 mm HoCl3) ones. Our model also reproduced well the distance‐dependent behaviour (Figure 1 D, solid lines), emphasizing the interest of using substrate deformation to achieve a long‐range actuation of remote objects.

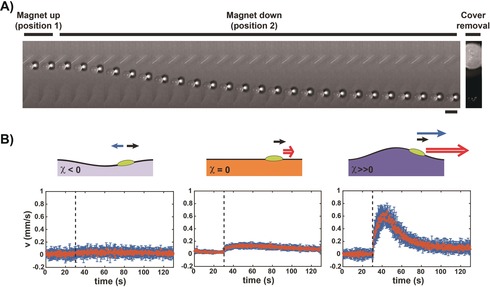

Liquid marbles have the remarkable advantage that they can encapsulate virtually any kind of liquid,32 making this method of transport particularly versatile. We then wanted to know whether it can be applied to conventional liquid drops without any specific coating. We thus performed the same experiment as in Figure 1 but using a 2 μL oil drop instead of a liquid marble. Interestingly, switching the magnet from position 1 to position 2 led to immediate motion of the drop (Figure 3 A and the Supporting Information, Movie S3). To our knowledge, this is the first magnetic actuation of a diamagnetic floating liquid drop, which does not rely on any magnetosensitive solid entities such as magnetic particles. To assess the contribution of the substrate deformation to the drop motion, we performed experiments on substrates of various magnetic susceptibilities. Similarly to what was observed with the liquid marble, we could not detect any significant motion when pure water was used as a substrate (Figure 3 B, left), confirming the importance of the paramagnetic nature of the substrate to achieve significant drop transport. Using a nonmagnetic substrate (17 mm HoCl3) in which no deformation occurred (Figure 3 B, middle), resulted in drop motion at a low speed (v max=0.2±0.04 mm s−1), which was due to the diamagnetic repulsion exerted on the drop (χ=−10.3±0.3×10−6). In contrast, the drop acquired a much higher speed (v max=0.7±0.1 mm s−1) when a strongly paramagnetic and thus highly deformable substrate (100 mm HoCl3) was used (Figure 3 B, right). The same trend was observed when the concentration of HoCl3 was varied in a systematic manner. Values of v max increased with an increase in [HoCl3], that is, when χ and therefore the substrate deformation increased (Supporting Information, Figure S4). In the same way as for the liquid marble actuation, these results showed that the magnetically induced motion of the drop on a paramagnetic substrate (Figures 3) was mainly driven by the substrate deformation, to which was added the weak contribution of the diamagnetic repulsion. The behaviour of the velocity as a function of distance to the magnet was also similar to that of liquid marbles (Supporting Information, Figure S5). Although the liquid marble and the oil drop had a similar magnetic susceptibility, the maximum speed for the drop was typically half that of the marble, which was attributed to a stronger dissipation at the liquid/liquid interface between the drop and the paramagnetic liquid substrate.

Figure 3.

Magnetic actuation of an oil drop. A) Kymograph of the magnet‐triggered motion of a 2 μL mineral oil drop on a 100 mm HoCl3 substrate using the same experimental set‐up as in Figure 1 A. The bright spot surrounded by a dark ring is the shadow of the drop. Frames are separated by 1.6 s. Scale bar=5 mm. The corresponding video is provided as Movie S3. B) Scheme (top) and speed as a function of time (bottom) of a 2 μL mineral oil drop on a water substrate containing different amounts of HoCl3: 0 mm (left, χ<0); 17 mm (middle, χ≈0); and 100 mm (right, χ≫0). Each graph shows the experimental speed data (mean±sd for 10 independent experiments) with an initial distance between the drop and the magnet axis within the range of 0–5 mm. The dashed line indicates the time at which the magnet was switched from position 1 to 2.

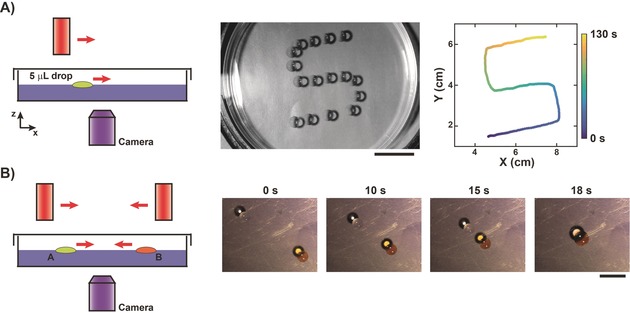

Finally, we explored how this new universal principle for magnetically induced motion of discrete liquid entities can be exploited for more complex operations of drop manipulation. First, using a mobile and portable magnet, drop motion could be maintained for extended periods of time and complex trajectories including curves (Figure 4 A and the Supporting Information, Movie S4) and self‐crossing points (Supporting Information, Figure S6 and Movie S5) were easily achieved with precision. Liquid marbles were also successfully transported along complex trajectories, such as “S” and “J” shapes (Supporting Information, Figure S7). To program drop fusion, we simply used a pair of mobile magnets to move two drops toward each other and therefore guide their fusion (Figure 4 B and the Supporting Information, Movie S6).

Figure 4.

Digital magnetofluidic operations: Complex transport and fusion. A) The magnet was placed at a distance of 12 mm from the surface of a 100 mm HoCl3 substrate and manually moved to direct the motion of a 5 μL mineral oil drop (left). Superposition of images (middle, each image separated by 8.6 s, scale bar=2 cm) and XY positions of the drop as a function of time (right) for an imposed S‐shaped trajectory. The corresponding video is provided as Movie S4. B) Two identical magnets were placed at a distance of 10 mm and moved manually to direct the motion of two 5 μL mineral oil drops, without (drop A) and with (drop B) Sudan II dye, and induce their fusion (left). Images show the magnetically induced drop fusion (right). The scale bar=1 cm. The corresponding video is provided as Movie S6.

In summary, we described a new mode of interfacial transport in which magnetic field‐induced liquid substrate deformation was used to actuate floating objects. This is the first method that allows the magnetically controlled actuation and manipulation of discrete liquid entities in air, which does not rely on the use of magnetosensitive particles. It was demonstrated to be particularly versatile as it is compatible with both conventional drops and liquid marbles; and any liquid, including most common diamagnetic liquids such as oil and water, can be actuated. Deformation‐based forces, especially capillary interactions, have been widely exploited to assemble or organize objects at interfaces,33 but deformation‐based fluidic transport27 has been a much more rarely explored principle.34 From a fundamental point of view, we showed that the contribution of the substrate deformation, even within a range of only a few microns, largely dominated that of the magnetic force exerted on the transported object. This made it possible to actuate the system with cost‐effective permanent magnets, paving the way for a new generation of microfluidic devices powered by miniature magnets and which are able to work without complex elements such as pumps, valves, or electrodes. This electric power‐free principle can also contribute to expanding the possibilities of low‐cost microfluidics and diagnostics,35, 36 making solutions developed in laboratories more broadly available to people and societies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) [European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007‐2013/ERC Grant Agreement No. 258782)], the Mairie de Paris [Emergence(s) 2012], the Institut de France (Subvention Scientifique Del Duca), the European Commission (FP7‐PEOPLE‐2013‐IEF/ Project 624806 “DIOPTRA”), and the Labex IPGG (ANR‐10‐LABX‐31). D.B. proposed the idea, conceived and supervised the entire project; S.R and N.K. optimized the liquid marble formulation; S.N.V., M.H., and J.V. built the magnetic actuation set‐up; J.V. and M.H. performed the magnetic actuation experiments on marbles (J.V.) and drops (J.V., M.H.) under supervision of M.A., M.M., and D.B.; J.V. and M.A. performed the surface deformation experiments; N.K. performed the theoretical work; all authors analyzed the data; D.B. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

J. Vialetto, M. Hayakawa, N. Kavokine, M. Takinoue, S. N. Varanakkottu, S. Rudiuk, M. Anyfantakis, M. Morel, D. Baigl, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16565.

Contributor Information

Jacopo Vialetto, http://www.baigllab.com/.

Prof. Dr. Damien Baigl, Email: damien.baigl@ens.fr.

References

- 1. Whitesides G. M., Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fair R. B., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2007, 3, 245–281. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baigl D., Lab Chip 2012, 12, 3637–3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cira N. J., Benusiglio A., Prakash M., Nature 2015, 519, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brzoska J. B., Brochard-Wyart F., Rondelez F., Langmuir 1993, 9, 2220–2224. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Velev O. D., Prevo B. G., Bhatt K. H., Nature 2003, 426, 515–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mugele F., Baret J.-C., J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2005, 17, R705–R774. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ichimura K., Oh S.-K., Nakagawa M., Science 2000, 288, 1624–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berná J., Leigh D. A., Lubomska M., Mendoza S. M., Pérez E. M., Rudolf P., Teobaldi G., Zerbetto F., Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diguet A., Guillermic R. M., Magome N., Saint-Jalmes A., Chen Y., Yoshikawa K., Baigl D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9281–9284; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 9445–9448. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diguet A., Li H., Queyriaux N., Chen Y., Baigl D., Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2666–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Venancio-Marques A., Barbaud F., Baigl D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3218–3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Venancio-Marques A., Baigl D., Langmuir 2014, 30, 4207–4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nguyen N. T., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2012, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pamme N., Lab Chip 2006, 6, 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coey J. M. D., Aogaki R., Byrne F., Stamenov P., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8811–8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown P., Bushmelev A., Butts C. P., Cheng J., Eastoe J., Grillo I., Heenan R. K., Schmidt A. M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2414–2416; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 2464–2466. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bormashenko E., Pogreb R., Bormashenko Y., Musin A., Stein T., Langmuir 2008, 24, 12119–12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nguyen N.-T., Zhu G., Chua Y.-C., Phan V.-N., Tan S.-H., Langmuir 2010, 26, 12553–12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Timonen J. V. I., Latikka M., Leibler L., Ras R. H. A., Ikkala O., Science 2013, 341, 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Long Z., Shetty A. M., Solomon M. J., Larson R. G., Lab Chip 2009, 9, 1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ooi C. H., Nguyen N.-T., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2015, 19, 483–495. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorvee J. R., Derfus A. M., Bhatia S. N., Sailor M. J., Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao Y., Xu Z., Parhizkar M., Fang J., Wang X., Lin T., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2012, 13, 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khaw M. K., Ooi C. H., Mohd-Yasin F., Vadivelu R., John J. S., Nguyen N.-T., Lab Chip 2016, 16, 2211–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aussillous P., Quéré D., Nature 2001, 411, 924–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kavokine N., Anyfantakis M., Morel M., Rudiuk S., Bickel T., Baigl D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11183–11187; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 11349–11353. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reisin C. R., Lipson S. G., Appl. Opt. 1996, 35, 1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laird P., Caron N., Rioux M., Borra E. F., Ritcey A., Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ooi C. H., Van Nguyen A., Evans G. M., Dao D. V., Nguyen N.-T., Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ooi C. H., Vadivelu R. K., St John J., Dao D. V., Nguyen N.-T., Soft Matter 2015, 11, 4576–4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McHale G., Newton M. I., Soft Matter 2015, 11, 2530–2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Whitesides G. M., Grzybowski B., Science 2002, 295, 2418–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu D. L., Bush J. W. M., Nature 2005, 437, 733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martinez A. W., Phillips S. T., Butte M. J., Whitesides G. M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1318–1320; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 1340–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bhamla M. S., Benson B., Chai C., Katsikis G., Johri A., Prakash M., Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary