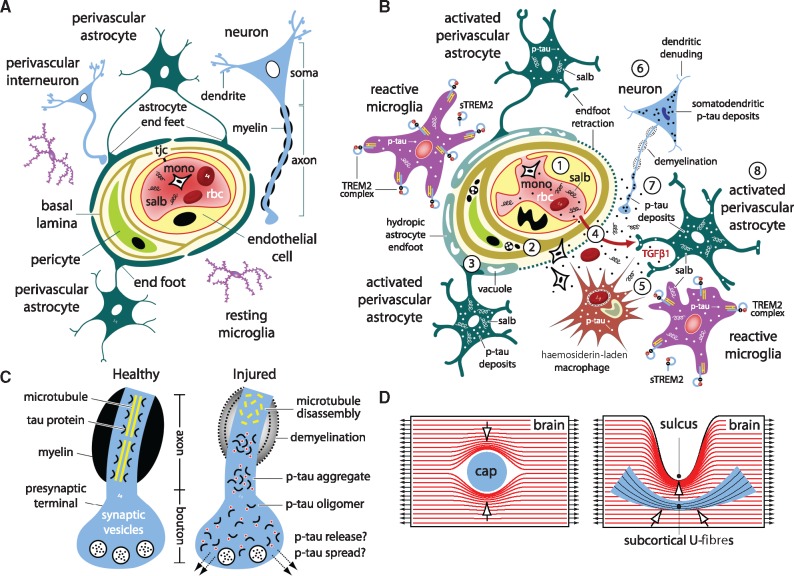

Figure 8.

Model of traumatic microvascular injury, blood–brain barrier disruption, microglial activation, perivascular neuroinflammation, myelinated axonopathy, and phosphorylated tauopathy after closed-head impact injury. (A) Brain capillary with intact blood–brain barrier and neurovascular unit. The contents within the capillary lumen include blood plasma, blood proteins (including serum albumin, salb) and formed elements (red blood cells, rbc; circulating monocytes, mono; other white blood cells and platelets, not shown). The capillary luminal wall is a structurally continuous sheath formed by endothelial cell membranes that are joined at intercellular clefts by tight junction complexes (tjc). The basal lamina separates endothelial cells from pericytes, multifunctional mural cells that support microvascular and neurovascular unit function. Astrocyte endfeet ensheath the abluminal capillary wall. The neurovascular unit comprises endothelial cells, astrocytes, pericytes, neurons, and extracellular matrix components that regulate blood–brain barrier function, gas exchange, and bidirectional transit of fluid, metabolites, nutrients, and signalling molecules between the blood and brain. (B) Injured brain capillary after neurotrauma. (1) Intraparenchymal shearing forces initiated by focal mechanical injury disrupt local microvascular structure and blood–brain barrier functional integrity. (2) Compensatory changes in the extracellular matrix, elaboration and expansion of the basal lamina, formation of stress granules, inclusion bodies, and autophagosomic vacuoles are indicative of traumatic microvascular injury and post-traumatic repair and remodelling. (3) Astrocytic endfoot engorgement (astrocytic hydrops), organelle degradation (autophagy, mitophagy), and vacuolization are prominent ultrastructural features of capillaries damaged by neurotrauma. Perivascular astrocytes assume a reactive phenotype with concomitant loss of endfoot organellar integrity and secondary fluid accumulation (presumably from vascular fluid transit and pump failure or endfoot membrane loss). Together these processes lead to loss of cellular polarity and astrocyte endfoot retraction (involution) along the abluminal capillary wall. (4) Post-traumatic alterations in microvascular structure further compromise blood–brain barrier integrity and promote extravasation of pro-inflammatory plasma proteins (e.g. serum albumin, salb) into the brain parenchyma. Damaged capillaries may also facilitate inflammatory cell diapedesis and red blood cell transit (microhaemorrhage) into the brain parenchymal. (5) Serum albumin and other blood proteins (e.g. fibrinogen) are highly stimulatory to astrocytes, microglia, and CNS-resident macrophage and drive cellular transformation from resting to reactive phenotypes. These and other molecular triggers induce local activation and phenotypic transformation of brain-resident microglia, including increased expression of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), an innate immune receptor expressed on the surface of activated microglia. Microglial TREM2 expression may be accompanied by endoproteolytic cleavage of the TREM2 ectodomain and shedding of the resulting cleavage product (sTREM2). Our results indicate that post-traumatic microglial activation and phenotypic transformation precede infiltration and accumulation of peripheral inflammatory cells at sites of focal brain injury. Localized clusters of hemosiderin-laden macrophage represent chronic residua of prior microhaemorrhage. (6) Secondary changes in neurons triggered by neurotrauma lead to axonopathy (e.g. demyelination, blebbing, axonal transport dysfunction, phosphorylated tau protein aggregation), dendritic denuding, hyperexcitability, synaptic dysfunction, and neurodegeneration. (7) Tau protein dissociates from microtubules, undergoes pathogenic phosphorylation (p-tau), aggregates abnormally within axons, and stimulates pathogenic transport to and miscompartmentalization within the soma and dendrites of traumatized neurons. (8) P-tau also accumulates in activated microglia, reactive astrocytes, and possibly other brain cells. P-tau propagation and spread may proceed via extracellular, paracellular, transcellular, and/or glympathic mechanisms. (C) Schematic representation of the axonal compartment of a healthy neuron (left) and traumatized neuron (right). In healthy neurons, tau protein associates with and stabilizes microtubules in axons and dendrites. In traumatized neurons, tau protein dissociates from microtubules and undergoes aberrant phosphorylation. P-tau is prone to pathogenic oligomerization, aggregation, and accumulation within axons, terminals, dendrites, spines, and soma of affected neurons. Miscompartmentalization of abnormally processed phosphorylated tau promotes release and transmission of p-tau species that contribute to progressive neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. (D) Internal force lines (red) show increased stress concentration at structural dishomogeneities in the brain. Anatomical features such as capillaries (cap), depths of cortical sulci, and grey-white matter interfaces are subject to shear stress amplification (stress concentration) and focal mechanical trauma (arrows). See text for details and discussion.