Abstract

Although gastric metastases have been estimated to occur in less than 2% of cancer patients, an increased use of upper digestive tract endoscopy allows for a higher detection of secondary gastric tumors. We describe the case of a 66-year-old male patient presenting with mild pain in the sternum and upper abdominal area. Physical examination revealed a right parietal skull tumor, with no other significant clinical changes. Upon exclusion of an acute coronary syndrome, upper digestive tract endoscopy was performed, showing the presence of an ulcerated tumor located in the gastric fundus. Histopathologic examination of the biopsy sample and immunohistochemical tests suggested a pulmonary origin of the gastric tumor. Whole body computer tomography showed the presence of tumors in the gastric fundus, left lung, liver, kidneys, bones and brain. Transbronchial biopsy of the lung tumor certified the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer, with the same immunohistochemical profile as the gastric tumor. Hence, it was considered the origin of the metastases. Biopsy of the skull tumor also had the identical tumor histology. Whole brain radiotherapy was performed for the brain metastases and subsequent chemotherapy was administered. Although non-specific, gastrointestinal signs and symptoms occurring in lung cancer patients should alert the clinicians as to the possibility of gastrointestinal metastases and prompt endoscopic evaluation.

Keywords: immunohistochemistry, gastric metastases, non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

During the last 20 years, novel therapies for lung cancer have led to the prevention of more than 1.7 million deaths (1). Even with this optimistic news, lung cancer remains the leading cause of death in USA (1). Approximately 50% of lung cancer patients have widespread metastatic disease at presentation, most frequently with cerebral, hepatic or adrenal involvement. The gastrointestinal tract is only rarely involved (2). The prognosis of gastric metastases with origin in lung cancer is very poor, survival rates being estimated at 20% at 1 year and 1% at 5 years (3,4). Although gastric metastases of lung cancer were believed to be exceptionally rare, autopsy studies report an incidence ranging from 0.19 to ≥11% (5–9).

Gastric metastases are rarely symptomatic and therefore easily overlooked when investigating lung cancer patients (10). Nevertheless, gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation have been reported and are often fatal. In light of these findings, an increased use of esophagogastroduodenoscopy may be needed to achieve a higher detection of secondary gastric tumors. For the early detection of gastric tumors one can enhance the performances of esophagogastroduodenoscopy by associating narrow band imaging (NBI) technology and in vivo staining examination techniques (11,12). The most frequent staining agents used for the assessment of digestive tract tumors are methylene blue, toluidine blue and Lugol iodine (13–15). The NBI technology improves specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of the methylene blue video staining method providing essential information regarding the superficial vascular network and the features of the cellular field (11). A thorough evaluation of tumor cell-specific characteristics utilizing ELISA assay and flow cytometry can improve the diagnostic and treatment protocol (16).

In the present study, we report a case of advanced lung cancer presenting as a symptomatic gastric tumor. This is an infrequent situation, only a few similar cases being reported in the past decades, to the best of our knowledge. We discuss the clinicopathological features of secondary gastric cancer with emphasis on the differential diagnosis and review the available treatment options.

Case report

A 66-year-old male patient, with a history of smoking, was admitted in August 2015 in the Department of Cardiology Elias Emergency Hospital (Bucharest, Romania) for mild pain in the sternum and upper abdominal area for >4 h. The physical examination revealed the presence of a right parietal skull tumor, the rest of the general examination being unremarkable. All cardiac causes for the pain were excluded and the patient was referred to the Department of Gastroenterology. Abdominal ultrasound was not relevant due to the patient's lack of compliance. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed the presence of an ulcerated tumor 80×70 mm in size located in the gastric fundus.

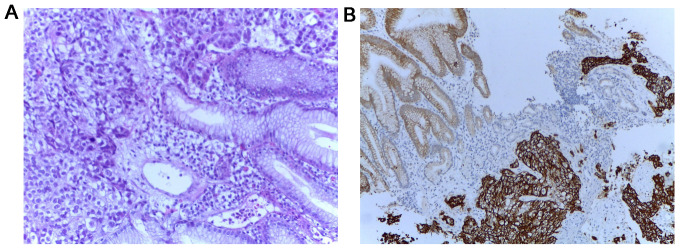

Multiple endoscopic biopsies were performed as well as a histopathologic examination, followed by hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining. Positive tumor protein 63 (P63), positive cytokeratin 34βE12 (CK34βE12), weakly positive thyroid transcriptional factor-1 (TTF-1), negative cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and negative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Fig. 1) confirmed the diagnosis of gastric metastasis of pulmonary origin.

Figure 1.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (×20) and immunohistochemical staining (×10) results of the gastric tumor biopsy showing poorly differentiated carcinoma. (B) Strongly positive CK34βE12 staining.

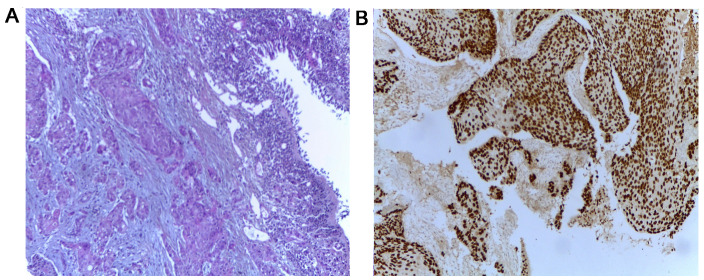

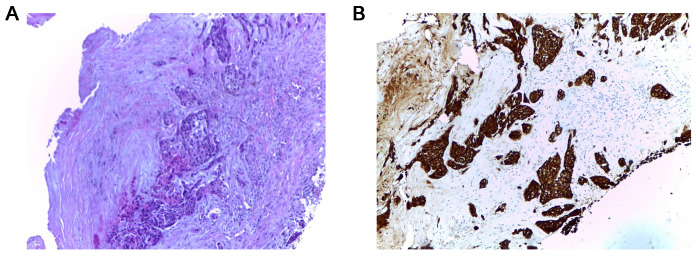

Whole body computed tomography (CT) scan identified multiple tumors: One in the gastric fundus, one in the left lung and numerous tumors in the liver, kidneys, bones and brain, the clinical stage being cT2N3M1. Bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy of the left lung tumor were carried out to establish the origin of the lung tumor (Fig. 2) leading to the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or non-small cell lung cancer. As the lung and gastric tumor had identical immunohistochemical profiles, it was considered the origin of the metastases. The tissue tested negatively for EGFR mutation and no ALK rearrangement was reported. Biopsy of the skull tumor also showed the same histologic pattern (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (×10), and (B) immunohistochemical staining (×10) results of the transbronchial lung biopsy showing the invasion of squamous cell carcinoma and expression of P63.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (×10) and immunohistochemical staining (×10) results of the skull tumor biopsy showing carcinoma with morphology similar to that of the primary tumor in (A) the lung. (B) Strongly positive CK34βE12 staining.

Laboratory findings showed no specific changes. Whole brain radiotherapy was performed for the brain metastases (total dose, 30 Gy). It was well tolerated, with no serious adverse events. Following radiotherapy, the patient underwent chemotherapy with paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC6 and osteoclast inhibitors (zoledronic acid), measured as q3w. After the second cycle, grade II aplastic anemia and mild elevation of liver enzymes occurred. Nevertheless, the oncology board, comprising a medical oncologist, gastroenterologists and hematologists continued the aggressive treatment, with daily monitoring of the hemogram and liver enzymes.

The patient received 6 cycles of chemotherapy, with stable disease, according to response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST). Due to grade IV anemia and hepatotoxicity from chemotherapy, oncological treatment was ceased and the patient offered best supportive care. The patient succumbed four weeks later to multiple organ failure.

Discussion

Gastric site metastasis from primary lung cancer was rarely reported, portending an inferior prognosis even with aggressive oncologic treatment (17). Breast cancer, esophageal cancer, melanoma, as well as testicular seminoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, choriocarcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma can also be the origin of secondary gastric tumors and should be included in the differential diagnosis (18–21).

In 1993, large cell lung cancer was reported to be the most common histologic type of primary lung cancer associated with gastric metastases (22). Nevertheless, according to more recent reports, pulmonary adenocarcinoma has become the leading disease, followed by SCC, small cell lung cancer, and pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung (23). The distinction between subtypes is critical for the selection of appropriate targeted therapies (erlotinib/crizotinib/bevacizumab/pemetrexed).

Lung cancer cells spread hematogenously to the gastric submucosa (17). The tumor is thus clinically silent until it reaches considerable sizes. Although non-specific, symptoms and signs such as epigastric pain, vomiting, anorexia and chronic upper gastrointestinal bleeding manifesting as melena and anemia occurring in cancer patients should alert the clinician and prompt endoscopic evaluation (17,24). However, such complaints are generally misinterpreted as side-effects of chemotherapy. Severe complications including acute bleeding and perforation may also occur and are usually lethal.

Endoscopic findings can mimic other gastric tumors, but a volcano-like or umbilicated mass (‘the bull's eye sign’) is considered a classic endoscopic appearance of metastatic gastric cancer, as was first suggested by Pomerantz and Margolin in 1962 (25). Nodules, solitary or multiple, sometimes ulcerated polypoid submucosal masses, as well as infiltrating constricting tumors have also been described (25–28). The most frequent locations of gastric metastases are reported to be the middle or upper third of the stomach. Usually, the greater curvature is involved (29,30). Given the variable morphology and the lack of characteristic appearances on endoscopy, metastases to the stomach may also be confused with gastric ulcer, ectopic pancreas, eosinophilic granuloma, lymphoma, carcinoid and Kaposi's sarcoma (31).

The histopathologic examination of gastric tumors in lung cancer patients raises yet another diagnostic challenge given the difficulty to distinguish between a metastasis from primary lung cancer and an initial gastric cancer, especially when considering adenocarcinoma. Hence, immunohistochemical tests are the most important step in the diagnostic algorithm of these cases and are crucial for optimal management (26). The common markers used for subtyping non-small cell lung cancer include TTF-1, CK7, Napsin-A for adenocarcinoma and p63, CK5/6, and CK34βE12/CK903 for SCC (32). In our patient, the positive P63 and CK34βE12 staining and the weakly positive TTF-1 staining support the lung origin of the metastasis.

Serum tumor markers were tested in order to complete the diagnosis: CEA and SCC levels were 3-fold higher than normal values, CA 19-9 was within reasonable limits. It is known that, each serum tumor marker has its specificity and sensitivity and can be used mainly to establish the prognosis of the disease. Non-small cell lung cancer also demonstrated the overexpression of endocan (33). This marker of angiogenesis was studied in several types of cancer and was used as a possible prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer and gastrointestinal cancer (34–36).

Gastrointestinal metastases secondary to lung cancer represent a late stage of disease, usually being associated with metastases in other organs. Patients rarely survive longer than 16 weeks after diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastases (9).

The therapeutic management of such patients includes surgery, chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy, molecularly targeted therapies and supportive care. Surgical intervention in patients with lung cancer metastatic to the stomach remains controversial as some authors report longer survival rates in the best supportive care approach (37), while others support metastasectomy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and unique metastasis not involving the brain or the adrenal gland (38,39). However, life-threatening complications such as massive hemorrhage or perforation can be prevented by surgical intervention (37,40). Therefore, treatment should be personalized. Our patient did not undergo surgery given the presence of multiple other extrathoracic metastases. We managed to control the disease and patient's symptoms for 22 weeks by offering 6 cycles of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and best supportive care when his performance status did not allow us to continue active oncological treatment.

In conclusion, although non-specific, gastrointestinal signs and symptoms occurring in lung cancer patients should alert the clinicians as to the possibility of gastrointestinal metastases and prompt endoscopic evaluation. Distinguishing between primary and secondary gastric tumors can be challenging and requires immunohistochemical tests. Early detection of gastric metastases and initiation of appropriate treatment can improve the patient's quality of life and prolong patient survival.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang CJ, Hwang JJ, Kang WY, Chong IW, Wang TH, Sheu CC, Tsai JR, Huang MS. Gastro-intestinal metastasis of primary lung carcinoma: Clinical presentations and outcome. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green LK. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach. A review of 67 cases. Cancer. 1990;65:1596–1600. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900401)65:7<1596::AID-CNCR2820650724>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MS, Kook EH, Ahn SH, Jeon SY, Yoon JH, Han MS, Kim CH, Lee JC. Gastrointestinal metastasis of lung cancer with special emphasis on a long-term survivor after operation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SY, Ha HK, Park SW, Kang J, Kim KW, Lee SS, Park SH, Kim AY. Gastrointestinal metastasis from primary lung cancer: CT findings and clinicopathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W197–W201. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillers TK, Sauve MD, Guyatt GH. Analysis of published studies on the detection of extrathoracic metastases in patients presumed to have operable non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 1994;49:14–19. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeill PM, Wagman LD, Neifeld JP. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1987;59:1486–1489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870415)59:8<1486::AID-CNCR2820590815>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antler AS, Ough Y, Pitchumoni CS, Davidian M, Thelmo W. Gastrointestinal metastases from malignant tumors of the lung. Cancer. 1982;49:170–172. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820101)49:1<170::AID-CNCR2820490134>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanescu DC, Ceachir O, Zainea V, Hainarosie M, Pietrosanu C, Ionita IG, Hainarosie R. Methilene blue video contact endoscopy enhancing methods. Rev Chim. 2016;67:1558–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hainarosie R, Ceachir O, Zainea V, Hainarosie M, Pietrosanu C, Zamfir C, Stefanescu DC. The test of lugol iodine solution associated with NBI examination in early diagnostic of tongue carcinoma. Rev Chim. 2017;68:226–227. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanescu DC, Ceachir O, Zainea V, Hainarosie M, Pietrosanu C, Ionita IG, Hainarosie R. The use of methylene blue in assessing disease free margins during CO2 LASER assisted direct laryngoscopy for glottis cancer. Rev Chim. 2016;67:1327–1328. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hainarosie R, Zainea V, Ceachir O, Hainarosie M, Pietrosanu C, Stefanescu DC. The use of methylene blue in early detection of the vocal fold cancer. Rev Chim. 2017;68:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanescu DC, Ceachir O, Zainea V, Hainarosie M, Pietrosanu C, Ionita IG, Hainarosie R. The value of toluidine blue staining test in assessing disease free margins of oral cavity carcinomas. Rev Chim. 2016;67:1255–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrică-Matei GG, Iordache F, Hainăroşie R, Bostan M. Characterization of the tumor cells from human head and neck cancer. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menuck LS, Amberg JR. Metastatic disease involving the stomach. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:903–913. doi: 10.1007/BF01070875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okazaki R, Ohtani H, Takeda K, Sumikawa T, Yamasaki A, Matsumoto S, Shimizu E. Gastric metastasis by primary lung adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:395–398. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i10.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLemore EC, Pockaj BA, Reynolds C, Gray RJ, Hernandez JL, Grant CS, Donohue JH. Breast cancer: Presentation and intervention in women with gastrointestinal metastasis and carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:886–894. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CP, Cheng JS, Lai KH, Lo GH, Hsu PI, Chan HH, Hsu JH, Wang YY, Pan HB, Tseng HH. Gastrointestinal metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Radiological and endoscopic studies of 11 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:536–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senadhi V, Dutta S. Testicular seminoma metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract and the necessity of surgery. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:499–501. doi: 10.1007/s12029-011-9274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa N, Yamasawa F, Kanazawa M, Kawashiro T, Kikuchi K, Kobayashi K, Ishihara T, Kuramochi S, Mukai M. Gastric metastasis of primary lung cancer. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;31:1390–1396. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Q, Su X, Bella AE, Luo K, Jin J, Zhang S, Luo G, Rong T, Fu J. Clinicopathological features and outcome of gastric metastases from primary lung cancer: A case report and systematic review. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1373–1379. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casella G, Di Bella C, Cambareri AR, Buda CA, Corti G, Magri F, Crippa S, Baldini V. Gastric metastasis by lung small cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4096–4097. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pomerantz H, Margolin HN. Metastases to the gastrointestinal tract from malignant melanoma. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1962;88:712–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sileri P, D'Ugo S, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Lolli E, Franceschilli L, Formica V, Anemona L, De Luca C, Gaspari AL. Solitary metachronous gastric metastasis from pulmonary adenocarcinoma: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scobie BA. Malignant gastric ulcer due to metastasis. Australas Radiol. 1966;10:119–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1966.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu CC, Chen JJ, Changchien CS. Endoscopic features of metastatic tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 1996;28:249–253. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu MH, Lin MT, Lee PH. Clinicopathological study of gastric metastases. World J Surg. 2007;31:132–136. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oda KH, Kondo H, Yamao T, Saito D, Ono H, Gotoda T, Yamaguchi H, Yoshida S, Shimoda T. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: Analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy. 2001;33:507–510. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YI, Kang BC, Sung SH. Surgically resected gastric metastasis of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:278–281. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i10.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reis-Filho JS, Carrilho C, Valenti C, Leitão D, Ribeiro CA, Ribeiro SG, Schmitt FC. Is TTF1 a good immunohistochemical marker to distinguish primary from metastatic lung adenocarcinomas? Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196:835–840. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(00)80084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grigoriu BD, Depontieu F, Scherpereel A, Gourcerol D, Devos P, Ouatas T, Lafitte JJ, Copin MC, Tonnel AB, Lassalle P. Endocan expression and relationship with survival in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4575–4582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldner MJ, Wirtz S, Jefremow A, Warntjen M, Neufert C, Atreya R, Becker C, Weigmann B, Vieth M, Rose-John S, et al. VEGF receptor signaling links inflammation and tumorigenesis in colitis-associated cancer. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2855–2868. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatfield KJ, Lassalle P, Leiva RA, Lindås R, Wendelboe Ø, Bruserud Ø. Serum levels of endothelium-derived endocan are increased in patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2011;16:351–356. doi: 10.1179/102453311X13127324303434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voiosu T, Bălănescu P, Benguş A, Voiosu A, Baicuş CR, Barbu M, Ladaru A, Nitipir C, Mateescu B, Diculescu M, Voiosu R. Serum endocan levels are increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Lab. 2014;60:505–510. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2013.130333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee PC, Lo C, Lin MT, Liang JT, Lin BR. Role of surgical intervention in managing gastrointestinal metastases from lung cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4314–4320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aokage K, Yoshida J, Ishii G, Takahashi S, Sugito M, Nishimura M, Ochiai A, Nagai K. Long-term survival in two cases of resected gastric metastasis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:796–799. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817c925c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salah S, Tanvetyanon T, Abbasi S. Metastatectomy for extra-cranial extra-adrenal non-small cell lung cancer solitary metastases: Systematic review and analysis of reported cases. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goh BK, Yeo AW, Koong HN, Ooi LL, Wong WK. Laparotomy for acute complications of gastrointestinal metastases from lung cancer: Is it a worthwhile or futile effort? Surg Today. 2007;37:370–374. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3419-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]