Abstract

The rapidly growing field of functional, molecular and structural bio-imaging is providing an extraordinary new opportunity to overcome the limits of invasive liver biopsy and introduce a “digital biopsy” for in vivo study of liver pathophysiology. To foster the application of bio-imaging in clinical and translational research, there is a need to standardize the methods of both acquisition and the storage of the bio-images of the liver. It can be hoped that the combination of digital, liquid and histologic liver biopsies will provide an innovative synergistic tri-dimensional approach to identifying new aetiologies, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the optimization of personalized therapy of liver diseases and liver cancer. A group of experts of different disciplines (Special Interest Group for Personalized Hepatology of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, Institute for Biostructures and Bio-imaging of the National Research Council and Bio-banking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure) discussed criteria, methods and guidelines for facilitating the requisite application of data collection. This manuscript provides a multi-Author review of the issue with special focus on fatty liver.

Keywords: Biobank, Bio-imaging, Fatty liver, Genomics, Liver biopsy, Liver cancer, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Magnetic resonance, Radiomics, Ultrasound

Core tip: The manuscript provides an extended expert review on the issue of bio-imaging of the liver with special focus on fatty liver and the need for a new integrated approach to bio-banking.

INTRODUCTION

Autopsy, from the Greek autopsía, namely seeing with our own eyes or direct examination after death, gave birth to modern pathology during the Italian Renaissance when autopsies were performed by such artists as Leonardo da Vinci to paint and sculpt the human body and by such medical doctors as Benivieni to understand the causes of death. Two and half centuries later, the father of anatomical pathology Morgagni executed hundreds of autopsies and released the monumental five-volume On the Seats and Causes of Disease[1]. The first liver aspiration biopsy on a living patient was performed in 1883 by Paul Ehrlich, but the breakthrough that allowed the spread of liver biopsy as a diagnostic tool in clinical practice was the simple and effective technique invented by Menghini in 1958[2]. The combination of liver histology from conventional biopsy and circulating biomarkers (liquid biopsy) helps in generating an understanding of the interplay between genes and epigenetic factors in physio-pathogenic processes, providing a bimodal approach for the study and understanding of liver physio-pathology. The liver biopsy specimen however, provides a random sampling of just 1/150000th of the liver, and as such is subject to considerable sampling errors in cases with an inhomogeneous distribution of the pathologic lesion[3]. Moreover, it is obtained by an invasive procedure, unsuitable for the repeated sampling necessary to follow the in vivo dynamics of many physio-pathologic mechanisms. In addition, in the process of fixation and staining, the melting of intracellular fat results in artifactual ghost droplets. In short, histology provides a dead, isolated frame from a living film that runs throughout the liver, and this has deeply limited the advancement of knowledge regarding the physiopathology of fatty liver.

Modern biomedical imaging techniques offer an attractive non-invasive option for the in vivo study of liver physiopathology and have the capacity to provide detailed anatomical and biochemical information on the whole organ, thereby overcoming the limit of sampling error. The combination of image-based digital liver biopsy with liver histology and liquid biopsy could yield a new multimodal approach to the study of the fatty liver in clinical pathology. To foster this approach in clinical and translational research there is a need to standardize the methods of both acquisition and storage of bio-images of the liver.

ACQUISITION OF HEPATIC BIO-IMAGES

Biomedical tomographic images are rich in information that is increasingly subject to quantitative radiological assessment. A major development in computer-aided research and diagnosis in recent years is based on computing multiple image features from volumes of interest (VOIs) or regions of interest (ROIs) of an organ and/or pathological tissue, and linking them to clinical or physio-pathological features, namely radiomics[4-6]. Automatic and semiautomatic image algorithms are mandatory for computing large numbers of image features from standardized VOIs and or ROIs for 2D/3D[7-12]. After computation, the image features can be used in correlation studies with physio-pathological and clinical characteristics and to build predictive models[13,14]. Because many of the computed features are correlated, appropriate machine learning methods are useful for establishing sustainable pattern recognition analysis[15-17].

In parallel to these developments, a great deal of new knowledge about the physiopathology of fatty liver disease has been accumulated in recent years, revealing the complexity of the mechanisms involved in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and the severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation[18-20]. The most recent guidelines and expert opinions for the management of NAFLD patients call for a new, systems medicine approach to the study of the interplays between the major physiology systems that control the vital relations of the liver with the environment, brain and nervous system, endocrine system, digestive system (gut and microbiota) and immune system[19]. New concepts for patient stratification are needed to identify different clinically significant profiles within the generic context of metabolic-syndrome[18]. This is especially important given that NAFLD affects almost one third of the general population, is an emerging cause of liver related mortality, and no reliable predictors of disease progression and response to therapy are yet available that can be applied on a large scale.

In keeping with this premise, we propose the digital liver biopsy as a new paradigm for full exploiting the information contained in multi-modality or multi-contrast conventional and molecular liver imaging, with the aim of establishing a comprehensive platform of liver radiomics, capable of capturing the heterogeneity of liver pathology associated with intra-hepatic fat accumulation. Central to our vision is that digital liver biopsies be archived together with stored specimens from both liquid and histologic biopsies in a national bio-imaging repository network including reference hepatology units and an accredited biobank hub[21]. This will foster the advancement of liver radiomics analysis, incorporating multiple texture and intensity-based features to identify those consistent with morphological transformations and highly correlated with clinic-pathologic characteristics. These imaging biomarkers will increase the potential of translational and clinical research and properly address several unmet needs for precision medicine[22-25]. The approach also encourages studies combining new imaging techniques with liver and blood metabolomics, as well as the analysis of the interplay between specific genes and the epigenetic factors conditioning their expression; opening a very interesting new way to target the dynamics of the pathogenic processes involved in NAFLD/NASH. While we hope that these new studies will identify different aetiologies, new diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and therapy targets; the underlying aim is to establish a basis for better patient stratification in respect to both prevention and outcome prediction that can support personalized treatment of NAFLD. The starting points for such work are the imaging technologies that are already well-established in clinical routine or well-advanced as imaging biomarkers. From current translational research and clinical practice there are several relevant PET/TC developments, as well as offshoots of ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging techniques[24-27].

LIVER ELASTOGRAPHY FOR ASSESSMENT OF FIBROSIS

Liver stiffness has been measured using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), ultrasound-based transient elastography (TE, Fibroscan), and acoustic radiation force impulse imaging techniques in order to assess fibrosis for defining different degrees of the disease and predicting clinical outcomes[28-32]. Despite their many advances, these techniques have several limitations that must be taken into account[33-36]. TE for instance, is hampered by the presence of significant fat and/or fluid between the chest wall and the liver. These result in unreliable TE measurements in about a quarter of obese patients: A figure that likely can be reduced using a larger probe, at least in non-severely obese individuals[35,36]. Lee et al[37] compared the diagnostic performance of transient elastography (TE) with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging (ARFI) for staging fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver stiffness correlated with fibrosis stage (P < 0.05) and the area under the ROC curve of TE (kPa) was slightly better than ARFI (m/s), namely 0.757 vs 0.657. MRE is more accurate than TE, especially for detection of initial stages of liver fibrosis, but it is influenced by iron overload and requires additional hardware[38]. Other limitations of MR elastography are technical, such as ensuring coupling of the driver to the abdomen, and ensuring that wave interference and attenuation do not compromise the stiffness values in some parts of the liver. Despite these obstacles and the limited clinical use seen at present due to expense and restricted availability, it is expected that MRE will come to represent the “gold standard” for tissue stiffness measurement[39,40].

The most important limitation of liver stiffness measures is that they are surrogates of liver fibrosis rather than a metric of fibrosis itself. Moreover, fibrosis is just one of the three major pathophysiological vectors, that determine liver stiffness; the others being congestion and inflammation[33,34]. The impact of congestion can easily be ruled out in patients without right heart failure through examination under standard fasting conditions, but there remains a need for additional clinical and pathological information and/or biomarkers to precisely characterize the different and relative contributions of inflammatory and/or fibrotic processes to liver stiffness in the single patient[34].

MAGNETIC RESONANCE RELAXOMETRY FOR ASSESSMENT OF FIBROSIS

Contrast in MR images is the product of exponential relaxation processes, the time constants of which (T1, T2, and T2*) are determined by the physico-chemical environment of the tissues. While T2 values are typically dominated by tissue water content, the use of T2 measurements for characterizing liver inflammation is complicated by iron sequestration and storage in hepatocytes. In fact, the use of T2 shortening (seen with spin-echo sequences) is well established for estimating high levels of iron overload, while T2* shortening (evident with gradient echo sequences) being more iron-sensitive is used in characterizing low levels of iron content. Similarly, several studies[24,41,42] have reported that liver T1 varies with degree of fibrosis. A number of fast imaging approaches have been developed that permit whole-liver T1 and T2 mapping within a small number of breath-holds, raising the potential for their clinical use. As yet however, these techniques are not widely available and need to be validated for use as surrogate endpoints in clinical trials[43].

Building on these components, a multi-parametric MR strategy has recently been established[26] that includes T1 mapping for the in vivo characterization of fibrosis/inflammation, T2* mapping for liver iron quantification, and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) for liver fat quantification (see below) without the intravenous injection of contrast agents. A good agreement with histology was shown in a cohort of patients with chronic liver disease of different etiologies[26]. Excitingly, other emerging MR biomarkers, including magnetization and saturation transfer, intra-voxel incoherent motion imaging, and perfusion mapping, most of which are well established in neurological imaging, offer potential to further characterize fibrosis, but remain to be optimized and adapted to liver imaging.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY FOR ASSESSMENT OF STEATOSIS

Sensitivity to the subtle differences in magnetic fields affecting atoms of a given species due to their different positions within a molecule or in different molecules has rendered magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) one of the most powerful tools in biochemistry. In the face of the complex chemical environment of the liver, and in the modest static magnetic fields available for in vivo use, however, the scope for MRS is greatly limited. Nonetheless, in expert hands, it is considered a gold standard technique for ex vivo evaluation of tissue fat content and commonly used as an in vivo reference standard[45-47]. In terms of analysis, MRS is straightforward. One simply integrates the area under the water and the individual fat component peaks of the hydrogen spectrum, and then calculates the ratio of fat signal to the total hydrogen signal.

Although the acquistion of the hydrogen spectrum is relatively fast, there are a number of difficulties with this technique. Firstly, it measures only in a small region of the liver, and so lacks information on heterogeneity within the liver. Second, the positioning of the volume is subject to uncertainty due to patient respiration – in particular differences in breath-hold position between planning and acquistion can produce large errors in the fat fraction estimation[48]. Third, the presence of iron accumulation can affect the reliability of the measurement. One approach for overcoming the limit of a single sampling volume is to perform MRS in multiple voxels simultaneously so that an image can be formed (chemical shift or spectroscopic imaging)[47]. Relative to conventional MRS however, spectroscopic imaging is time consuming, and requires specialized pulse sequences that are not uniformly available across centres. More importantly, the resolution of the images remains rather poor, and contamination errors due to blurring reduce the accuracy of fat fraction measurements. In fact, at least one report has suggested that neither MR spectroscopy nor chemical shift imaging provide adequate accuracy for clinical decision-making[46].

PROTON-DENSITY FAT FRACTION MEASUREMENT

When observed in weak magnetic fields (≤ 1T), the MR spectrum of fat is largely reduced in its primary peak associated with hydrogen bound to carbon along the backbone of the fat molecule (triglycerides). This observation has given rise to a widely used method of creating water and fat images in MRI that was initially proposed by Dixon[48]. Because of their different resonant frequencies, the water and the primary fat peak cycle in and out of phase after excitation. The difference between an image formed when the peaks are in-phase and one formed when they are out-of-phase is proportional to the quantity of fat present and one can readily calculate a fat fraction. A significant limitation of this “two-point” Dixon (or in-phase: out-phase) technique is ambiguity as to which (i.e., water or fat) is the dominant component. Uncorrected, the assumption that water dominates leads to significant errors when the fat fraction exceeds 50%[45]. In the liver, a further complication of the two-point Dixon technique is associated with the presence of iron, which can be increased several hundredfold in patients with iron overload[44]. At elevated iron contents, the MR signal decays significantly between the in and out of phase echoes, creating an artificial elevation of the fat fraction (or reduction if the out of phase echo is acquired first).

At higher magnetic field strengths, and in the presence of good magnetic field shimming, the hydrogen spectrum becomes more complex as the different physical-chemical environments occupied by hydrogen within fats contribute additional frequencies (chemical shifts) relative to water. As not all of the peaks are in-phase (nor out-of-phase) at any given time, the additional peaks produce variability in the fat fraction estimates when using the two-point Dixon technique[48]. To deal with the errors due to the contributions from the minor fat peaks in the hydrogen spectrum, Yu et al[49] proposed the use of multi-component model fitting to multi-echo MRI data to produce proton density fat fraction (PDFF) measurements. After a rapid evolution to further account (up to certain limits) for ambiguities in water or fat dominance, T2* effects associated with iron content, and the possibility to perform quantification with or without phase information[50-54], PDFF has emerged as the preferred MR imaging strategy for fat quantification[55].

Although PDFF measurements[56] have been reported to better correlate with biochemical analysis (Folch method[57]) than with the conventional histopathology grading of fat content, there is a relatively good concordance between MRI-PDFF and liver histology[58,59]. Relative to the conventional Dixon technique, PDFF measurements offer increased accuracy and repeatability, and can be used to assess the full range of fat values with less risk of inversion between water and fat values. The fact that the entire liver can be examined with PDFF scans provides a considerable advantage over MR spectroscopy for measurement stability as a high number of voxels contribute to estimates of fat fraction in the liver as a whole or in individual lobes thereof. Achieving this improved performance however, requires care in the choice of imaging parameters acquisition, and software specifically adapted to the fitting process.

There are now numerous PDFF software solutions that offer varying degrees of support, cost and availability for clinical and research use. Most free-ware solutions for example, do not offer support either in use of the software, or for the optimization of imaging parameters and data preparation. The maturity, cost and support for commercially available software is varied, and their reliability and accuracy are still being established in practice.

INTRAHEPATIC FAT MEASURED BY ULTRASOUND

US imaging has many advantages over MRI/MRS since it is simple, quick, less expensive and well tolerated. Moreover, the equipment is relatively widely available and, if needed, can be brought to the patient and conventional US is already widely used for diagnosis and management of liver pathologies. However, while US provides reliable qualitative diagnosis of liver steatosis when liver fat is above roughly 20%[60-62], its quantitative assessment is considered unreliable due to operator dependence. As described above, US can be used to measure shear wave propagation as an indicator of liver stiffness in fibrosis[58,59] and the Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) score provided by Fibroscan (Echosens, Paris, France) was the first widely available quantitative US measure of intrahepatic fat in clinical practice[63,64]. It is based upon a single parameter, the US beam attenuation rate along a beam transmission line.

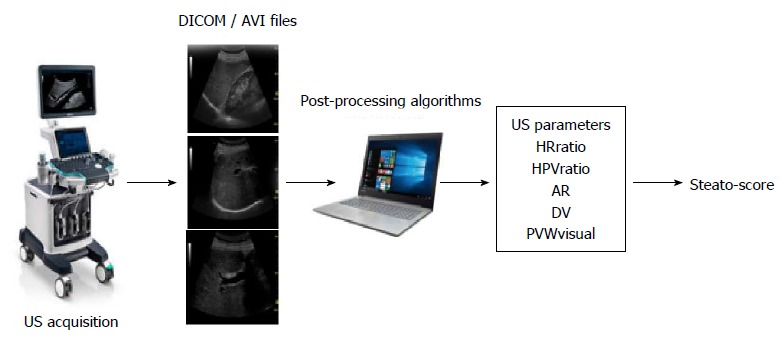

There is now a trend to adopting multi-parametric strategies to better assess steatosis quantitatively. One such approach is based on the acquisition of common scan projections (both subcostal longitudinal and oblique views) available with commercial US systems[65]. Two recordings (clips of 5 s) allow the quantification of 5 different parameters associated with intrahepatic fat accumulation (Figure 1). These include the hepatic-renal ratio (HRratio) and the hepatic-portal vein ratio (HPVratio)[60,61] that describe the echogenicity of the liver parenchyma in comparison with renal cortex and inner portal vein, respectively. In addition, the attenuation rate (AR) takes into account the reduction of US beam penetration[61], while grades are assigned to diaphragm visualization (DV, assessing the degree of diaphragm line visualization) and portal vein wall visualization (PVWvisual, assessing blurring of the portal vein walls). An algorithm (Steato-score) combining these five parameters showed good diagnostic performance discriminating presence (≥ 5%) or absence (< 5%) of steatosis relative to 1H-MRS with an area under the receiving operator characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.98 and roughly 90% specificity and sensitivity[65].

Figure 1.

Quantitative multi-parametric assessment of intrahepatic fat by ultrasound. Workflow of the image acquisition, processing and data elaboration leading to a score provided by an algorithm (Steato-score)[65]. US: Ultrasound; AR: Attenuation rate; DV: Diaphragm visualization.

In a further refinement, the five parameters (HRratio, HPVratio, AR, DV, PVWvisual) will be combined with texture analysis of the liver parenchyma in the images to discriminate multiple steatosis classes using machine learning approaches. Taking 1H-MRS values as ground-truth, the diagnostic performance of advanced algorithms will extend the quantification of higher intrahepatic fat levels by ultrasound[65-67].

PET TO STUDY LIVER METABOLISM

Positron emission tomography (PET) is able to image in vivo biochemical processes quantitatively; molecules labeled with positron-emitting radioisotopes are used in trace quantities (i.e., without pharmacological effect) to visualize and measure rates of biochemical processes in vivo. Among the various PET-tracers, the fluorinated glucose analogue [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), is the most widely used for metabolic, neurologic, and oncologic research as well as in clinical practice. Inflammatory and cancer cells are both metabolically active and show an increased uptake of FDG which is subsequently phosphorylated to FDG-6-phosphate and trapped intracellularly because most of FDG-avid cells, including inflammatory cell, do not express glucose-6-phosphatase. Hepatocytes on the other hand, do express this enzyme, and release FDG back into the blood.

Several studies have examined the potential of this difference in FDG kinetics in the study of fatty liver[68-70], comparing hepatic FDG uptake in NAFLD patients to controls using the semi-quantitative measurement of standardized uptake value (SUV). The results however, are mixed with some reporting a negative correlation between liver FDG uptake and NAFLD[69], others a positive[70] and others no association[69]. These conflicting results may be the consequence of the many factors, both physiological and technical that can affect SUV values[71,72]. Interestingly, FDG PET studies have nonetheless shown a link between vascular inflammation and NAFLD[73] as well as that liver SUV in patients with NAFLD may be a prognostic factor for cardio-cerebrovascular events[74,75].

From a metabolic point of view the options on PET tracers are manyfold providing a role to play in the study of NAFLD pathology. A first example is the study of hepatic metabolism in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome and its clinic-pathologic correlates (e.g., diabetes, hypertension and obesity). A negative correlation between higher hepatic glucose uptake HGU and liver fat content was reported in overweight subjects with type 2 diabetes[76]. These results support the notion that NAFLD is epiphenomenon of insulin resistance. The liver is an insulin sensitive organ[77] and thus, hepatic glucose uptake is reduced in subjects with insulin resistance.

Other aspects of liver metabolism such as fatty acid uptake, oxidation, and perfusion are also amenable to study with PET techniques. In a recent study in morbidly obese subjects, Immonen and coworkers, using a palmitate analog, [18F]-fluoro-6-thiaheptadecanoic acid (18F-FTHA), found morbidly obese subjects to have elevated hepatic fatty acid uptake (HFU) before bariatric surgery that decreased after surgery, though it did not normalize relative to lean subjects. Intriguingly, HFU and liver fat content in these patients were not related[78]. Iozzo et al[79] using 11C-palmitate-PET scanning showed that obese subjects have higher rate of fatty acid oxidation than lean subjects. According to these authors, the assessment of fatty acid oxidation is of major importance in characterizing subjects with NAFLD, since fatty acid oxidation is a significant source of reactive oxygen species in obesity-related hepatic lipotoxicity. Finally, with appropriate modeling, PET like MRI can be used in the quantification of liver perfusion in humans[78,80].

In the oncologic field, FDG-PET scanning is the gold standard, due to the avidity of tumors for glucose. Moreover, as used in this context, serial SUV measurements is a reliable tool, with the individual patient serving as their control before and after treatment. In hepatocellular carcinoma, FDG-PET has shown its usefulness both for identifying more aggressive tumors predictive of lower survival rates, and for capturing early signs of response to treatment. In pre-clinical models, FDG-PET scanning showed capacity to quantify tumor response[81] with potential usefulness in tumor monitoring. In the clinical setting, FDG-PET has proven useful as survival predictor: patients with lower tumor to liver ratio (TLR) at time 0 showed three times longer survival than patients with high TLR[82] and the SUVmax parameter was an independent predictor of survival in HCC patients undergoing Sorafenib treatment[83]. Most interestingly, the discriminating capacity of FDG-PET associated with the clinic pathologic response to the anti-angiogenetic drug was shown to be detectable as soon as three weeks from the beginning of treatment[84], thus an ealry FDG-PET scan after starting anti-angiogenetic treatment seem to be a promising technique for monitoring early response[85].

Undoubtedly, PET imaging in the liver has provided new insight in quantifying different metabolic pathways in humans. Whereas measuring inflammation in the liver until now has been proven challenging, FDG-PET has a clear role in patients affected from hepatocellular carcinoma.

IMAGING MASS SPECTROMETRY

IMS combines the mass spectrometry with the Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) technique, and allows the visualization of the spatial distribution of metabolites, drugs, peptides, proteins and lipids, directly on tissue sections without the need for extraction (biochemical analysis) or the use of specific markers (enzyme- or immune-histochemistry). The advantage of this technique is in mapping the subcellular localization and morphology on tissue sections and, at the same time, providing qualitative and quantitative evaluation of thousands of analytes. This bi-dimensional technique can also be adapted to fathom below the tissue surface to produce a three-dimensional map of the molecules (having molecular weights between 1000 to 70000 Da) present in the histological sections. The signals of ions obtained from the histological section/sample can be mapped in specific regions of the tissue and transformed into images on the basis of the density of the ions inside the tissue.

As an example of the use of IMS, accumulation of C14:1 acylcarnetine in a steatotic liver has suggested a deficiency of very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase permitting molecular genetics analysis to be addressed towards the detection of the underlying mutations[86].

There are in fact a growing number of techniques similar to IMS, including synchrotron infrared and ToF-SIMS (time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry) micro-spectroscopies[87] capable of identifying molecular species of lipids concentrated in steatotic vacuoles or present in small lipid droplets that most probably correspond to the first step of lipid accretion. Likewise these techniques are of interest for tracking and understanding the effects (pharmacokinetics, toxicology, metabolomics) of drugs on cells in metabolic diseases and NAFLD. While not applicable in vivo they are likely to play an increasing role in the chemical imaging/analysis of pathology samples to provide high resolution targets, in both spatial and biochemical terms for the understanding of radiological findings of NAFLD.

RADIOMICS

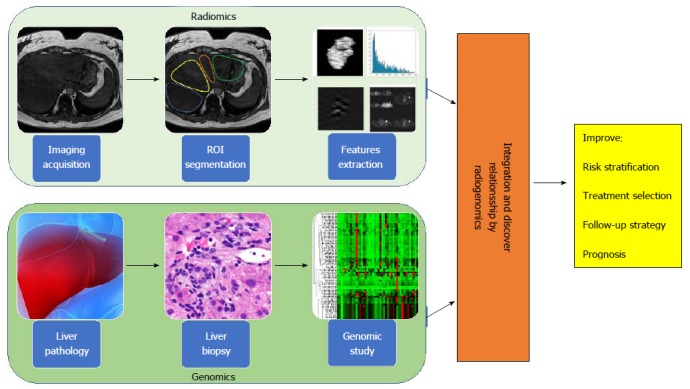

The success of precision medicine requires a clear understanding of disease heterogeneity at the single patient level, yet despite the large radiological armamentarium available, most imaging-based clinical decision-making is still based solely on visual assessment. The combination of visual assessment and image-processing techniques that describe and quantify numerous image features, such as intensity-based and textural properties that are difficult to convey consistenty in verbal reports, can provide a comprehensive characterization of imaging data sets. This approach adds value to the individual quantitative measure or visual subjective report and the derived results can be combined with statistical modelling techniques to predict clinical end points. The field of research that examines the relationships between advanced quantitative imaging features from medical images and clincal data is called “Radiomics”, while “Imaging Genomics” (or radiogenomics) refers to the study of imaging features in association with high-throughput genetic data[88] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radiogenomic approach to liver disease. Radiogenomics integrates radiomic data (upper panel), produced from the in silico extraction of features from bio-images, with genomic data (lower panel), coming from the study of bio-specimens with next generation sequencing technologies. Radiogenomics represents a powerful strategy to improve and personalize diagnostic accuracy, as well as measure response to therapy, leading to an overall improvement of patient management affected by liver disease.

Radiomic features are derived from the information contained in the voxels of a segmented structure of an image, and are typically grouped into families having similar derivational or statistical roots. First-order statistical features are reflected in the histogram of voxel intensities, and include: the mean value, dispersion (standard deviation, mean absolute deviation), central moments (skewness and kurtosis describing asymmetry and sharpness, respectively) and randomness (entropy, uniformity). Texture or greyscale variation features, refer to higher-order statistical measures that describe the local spatial arrangement of intensities. This typically reduces to expressing how different parent matrices capture the spatial intensity distribution of an image, and is widely used as a low-level step in pattern recognition. In contrast to the pre-defined features associated with texture analysis, the rapidly growing approach to radiomics represented by deep learning draws on advanced optimization of self-generated patterns to create networks for recognition analogous to neurons. While originally developed for planar images, intensity-based and textural features measures and deep learning can generally be calculated for volumetric datasets.

Radiomics analysis, as a technique that objectively measures the structural and/or functional heterogeneity of the tissue by quantifying the spatial patterns of pixel intensities on cross-sectional imaging, can improve the clinical usefulness of multimodal biopsy data. Recent pilot studies employing radiomic approaches on multimodal and hybrid imaging (CT, optical, PET/MRI, PET/CT) have shown the usefullness of quantifying the overall tissue spatial complexity in identifying the regions which drive disease transformation, progression, and drug resistance in a variety of pathologies[17,90-93].

Both radiomics and imaging genomics are at very early stages in hepatology and many problems remain to be solved. To date, the vast majority of liver-related radiomic studies have focused on the analysis of malignant lesions for establishing prognostic or predictive models. For example, in 2007, Kuo et al[88] observed significant correlation between tumour margins in arterial phase images and doxorubicin-response gene expression. In 2015, Miura and coauthors[96] identified 53 up-regulated and 71 down-regulated subsets of genes in the highly aggressive HCC group compared with the low-grade HCC group as distinguished by gadolinium ethoxybenzyl-DTPA magnetic resonance imaging hyperintensity. They have also shown that clinico-pathological and global gene expression analyses revealed low-grade malignancies within high-grade HCCs compared with low-grade HCCs. Recently, Zhou et al[97] have extracted radiomics features from arterial and portal venous phase using CT images, identifying twenty-one radiomics features from a panel of 300 candidate features, to predict the early recurrence (≤ 1 year) of hepatocellular carcinoma. A further example of the scope for synergy formed by the three-dimensional vision of digital, liquid and phsyical biopsy, is the recognition of relationships between histologic and clinical phenotypes including microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma evidenced via MRI diffusion-weighted imaging and hepatobiliary phase after gadoxetic acid[94,95].

In one of the few reports applying the radiomic approach to the study of NAFLD, in 2015 Vanderbeck et al[90] developed an automated classifier that detected and quantified macrosteatosis with at least 95% precision. They applied an automatic quantifier of lobular inflammation and ballooning to digital images of hematoxylin and eosin stained slides of liver biopsy samples from 59 individuals with normal liver histology and varying severity of NAFLD. Their results demonstrated that automatic quantification of cardinal NAFLD histologic lesions is possible, and offer promise for further development of automatic quantification of NAFLD biopsies in clinical practice.

Genome-wide association studies of hepatic fat content as determined radiologically on the other hand, have already led to major breakthroughs in the field, with the identification of genetic variants influencing hepatic fat accumulation[98,99]. In addition, although fibrosis stage is considered the major prognostic determinant in patients with NAFLD/NASH[100], recent data suggest that the amount of hepatic fat accumulation plays a causal role in determining the development of NASH and its progression[101]. Thus, a reliable non-invasive measure of intrahepatic fat may represent an important outcome predictor in both clinical research and practice.

Radiogenomics findings in hepatic oncology illustrate the potential for further clinical insights and diagnostic pathways. For example, Banerjee et al[106] found an interesting correlation between a “Radiogenomic Venous Invasion” biomarker (a contrast-enhanced CT parameter) and a 91-gene HCC “venous invasion” gene expression signature. This biomarker may be able to predict histological microvascular venous invasion in HCC that may be useful for identifying patients less likely to a durable benefit from surgical treatment. Renzulli et al[107] also found a correlation between multiple imaging biomarkers, such as tumor dimension, non-smooth tumor margins, peri-tumoral enhancement, and gene expression called “two-trait predictor of venous invasion”, as predictor of microvascular venous invasion.

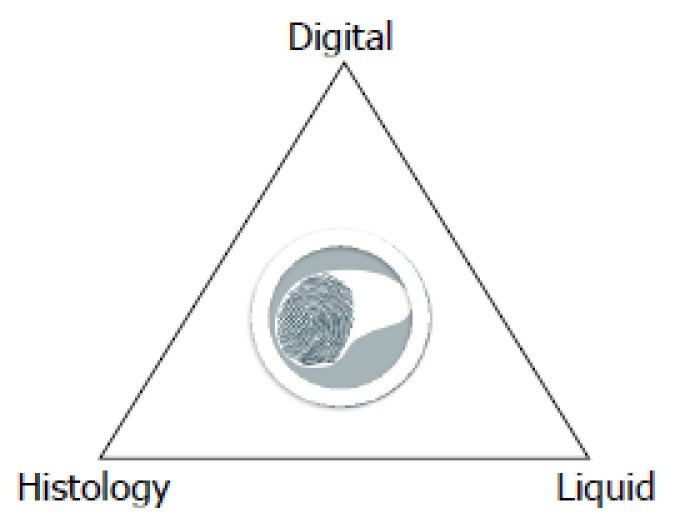

Hepatology is a particularly interesting field of application for the new radiogenomic approach; patient management already requires the combination of information coming from ex vivo analyses of circulating biomarkers (serum proteins, transaminases, etc.), histology and direct in vivo multimodal imaging data (ultrasound, CT, MR, etc.) (Figure 3). Nowadays however, all these data remain locked within the various departments and isolated between institutions, creating an obstacle to the creation of the coherent program of collaborative research.

Figure 3.

A new three-dimensional view of the liver biopsy. Digital biopsy, direct in vivo imaging of the whole liver, adds important pathophysiological and morphological context to liquid and invasive (percutaneous or surgical) liver biopsies that provide focal ex vivo analysis of circulating biomarkers and specimens of the liver respectively contributing to a three dimensional view for diagnosis and prognosis of liver disease.

BIO-BANKING FOR LIVER DISEASE

Institutional biobanks are service units dedicated to the collection, processing, storage and distribution of biological materials and associated patient information. Biobanks are becoming more and more central to translational research in the fields of human health, biotechnologies and development in life science.

Generally, institutional biobanks can be classified in terms of the profile of material contained in the collection as: population-based, disease-specific or rare disease oriented. The biological material can be constituted of different types of samples such as solid tissues, plasma, serum, RBC, buffy coats, white cells, DNA, RNA, proteins, cell lines, saliva, urine and fecal samples. The widest European consortium of Biobanks is represented by the Bio-banking and Bio-Molecular Research Infrastructure (BBMRI-ERIC)[103]. Recently, an additional class of biobanks has emerged in the form of imaging biobanks. Specifically, the European Society of Radiology defines imaging biobanks as “organized databases of medical images and associated imaging biomarkers (radiology and beyond) shared among multiple researchers, and linked to other biorepositories”[104,105]. The primary role of imaging biobanks is the identification of novel imaging biomarkers to be used in research studies, as well as to support validation of novel biological or genetic biomarkers of disease. It is important to recognize the fundamental importance of integrating clinical, pathlogical and biological endpoint data (such as with genomic results coming from high-throughput sequence analysis of DNA or RNA) with in vivo imaging data derived from radiomic analysis of CT, MRI or PET images for the identification of biomarkers (both imaging and non-imaging) and their translation to clinical relevance. A major limitation of radiomics and radiogenomics research is that the large number of radiomic features and patholgical/biological variables that may or may not be involved necessitate the use of large datasets and condivision of data across disciplines. Thus, imaging biobanks should be embedded in wider biobank networks. This may be the product of an explicit program of data collection (such as the German national Cohort, and the United Kingdom Imaging Biobank projects) or through consistent practice across a number of individual clinical entities that interact as nodes in a network dedicated to a given pathology/ies. As an example of a product of the former, in a prospective study of 4.949 participants in the United Kingdom Imaging Biobank[105] in whom liver fat was measured using the PDFF MRI technique, Wilman et al[105] showed an association of increased liver fat with greater age, BMI, weight gain, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. An example of an individual clinical node for the latter form of network is the SDN Biobank, that is the institutional biobank of the IRCCS SDN. This structure is devoted to the collection of biological material (blood, urine, feces) as well as images (deriving from CT, PET, MRI) from patients affected by oncological, cardiological, neurological and metabolic diseases[21].

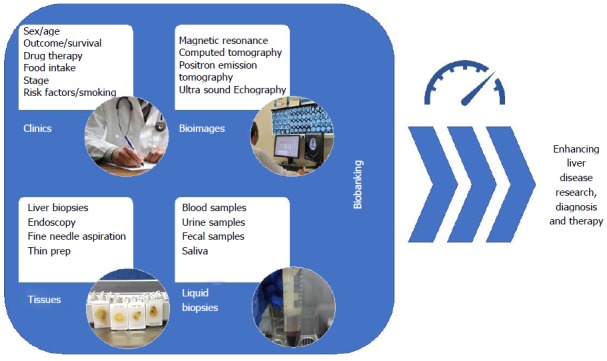

Due to the non-invasive nature of medical imaging and its ubiquitous use in clinical practice, the field of radiogenomics is rapidly evolving and initial results are encouraging. Biobanks will surely have a critical role for the development of the innovative radiogenomics protocols. Indeed, their collaboration across centres and disciplines is likely the only feasible approach to assembling the large numbers of images and samples, along with the clinical data required for testing associations in identifying and validating imaging and genomic biomarkers. To facilitate this collaboration, in the future it will be necessary to bring together images and biological samples from the same patients in innovative biobanks adapted to collect both kinds of material. The data coming from this kind of biobanks will have a critical role for the development of personalized protocols for diagnosis and patients care (Figure 4). In the context of fatty liver, well defined and correlated histologic and imaging targets from MRI and US (Table 1) already exist and they can form the basis of such a collection.

Figure 4.

Modern vision of bio-banking. The collection of patient clinical data, tissue samples, liquid biopsies as well as bio-images, in organized datasets is defined as “bio-banking”. With the advent of omics sciences (i.e., proteomics and genomics) where a large number of biological specimens and associated data are needed for making a precision medicine approach to the patients collaborative studies across centers are essential to maximizing patient recruitment. Equally, accessible well-structures data stores permit re-use and re-examination of data reducing the cost of subsequent studies. In this context, the field of bio-banking has the possibility to enhance research on liver disease as well as improve diagnostics and therapeutics.

Table 1.

Intrahepatic fat measurement

| Ref. | Imaging modality | Classification | ROC-derived parameters | ||

| AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |||

| Mancini et al[60] 2009 | US | 1H-MRS fat content > 5% | 0.996 | 100 | 95 |

| Xia et al[61] 2012 | US | 1H-MRS fat content > 5.56% | NA | 95.1 | 100 |

| Edens et al[62] 2009 | US | 1H-MRS fat content > 5.56% | NA | 66.7 | 100 |

| Di Lascio et al[65] 2018 | US | 1H-MRS fat content > 5% | 0.97 | 89 | 94 |

| Sasso et al[108] 2012 | CAP score (imaging derived) | Liver biopsy | S0 vs S1S2S3: 0.80 | S0 vs S1S2S3: 76 | S0 vs S1S2S3: 71 |

| S0: < 10% of hepatocytes | S0S1 vs S2S3: 0.86 | S0S1 vs S2S3: 87 | S0S1 vs S2S3: 74 | ||

| S1: 11%-33% of hepatocytes | S0S1S2 vs S3: 0.88 | S0S1S2 vs S3: 78 | S0S1S2 vs S3: 93 | ||

| S2: 34%-66% of hepatocytes | |||||

| S3: 67%-100% of hepatocytes | |||||

Both histologic and digital liver biopsy provided reliable measures of intrahepatic fat that are significantly correlated, but categorically different. Liver biopsy describes the histologic characteristics of the pathologic lesions and accounts for the percentage of hepatocytes with intracellular fat-derived vacuoles using categorical grading systems that are not directly representative of the hepatic triglyceride concentration[19-21]. On the other hand

H-MRS measures protons in acyl groups of liver tissue triglycerides and provides continuous quantitative values expressed as mg/g of hepatic tissue[109]. Moreover, 1H-MRS uses a much larger volume of liver tissue than biopsy reducing sampling error and representing the most accurate measure of the overall liver triglyceride content. US: Ultrasound; ROC: Receiving operator characteristic; CAP: Controlled attenuation parameter.

DIGITAL BIOPSY-THE ROAD AHEAD

Digital biopsies for NAFLD need to be fast and easy to obtain, and consistent among operators, technologies and methods, and most importantly provide clinically relevant results. To arrive at this level, there is a need for research, development and extensive collaboration.

A number of imaging techniques are already available for evaluation of fibrosis and steatosis. Wider adoption of these techniques and continued work to overcome their limitations can provide the basis for multi-centric collaboration on the optimization of imaging for fatty liver.

No individual centre has the breadth and depth of patients to go it alone in establishing a validated digital liver biopsy. Collaboration on imaging technique adoption should be performed in combination with establishing a cross-center imaging biobank linked to associated conventional biobanks.

An open need lays in the attraction of expertise and interest to carry out radiomics and radiogenomic studies and this follows the generation of data and the establishment of the bio-repository resources described above. Only at this point we will see the fruits of the labour, in terms of possible imaging biomarker signatures and associations with clinical and biological endpoints. Prospective studies should then compare the results obtained using images acquired at different points in time by multiple technicians, and read by both radiologists and trained non-radiologists. The next step is studying and comparing quantitative image features to unravel the relationships between the digital biopsy features and histopathologic, metabolic and genetic characteristics and building models which link them to the disease outcomes. Validation studies with multiple users are required to show that intra- and inter-reader variations of the digital biopsy derived features are acceptable.

CONCLUSION

We foresee the combination of image-based digital liver biopsy with liver histology and liquid biopsy in a multimodal approach to the study of the fatty liver in clinical pathology as a key to personalizing patient care. To foster this approach in clinical and translational research there is a need to standardize the methods of acquisition, processing and storage of bio-images of the liver. A number of imaging techniques that offer a starting point for acquisition have been identified and their use in combination in prospective studies will open a new venue of translational and clinical research. However, many of these tools are still limited to selected Centres and it is important to increase their accessibility by reducing costs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following investigators contributed equally to the critical revision and approval of the review: Stefano Bellentani (Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Santa Chiara Clinic, (Locarno, Switzerland); Luigi Coppola (IRCCS SDN Naples, Italy); Valerio Nobili (University “La Sapienza” of Rome and Hepato-metabolic Diseases and Liver Research Units, “Bambino Gesù” Children’s Hospital, Rome, Italy).

Footnotes

Supported by the Italian Ministry of Health Project, No. RF-2010-2314264. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 27, 2017

First decision: January 15, 2018

Article in press: February 25, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Abenavoli L, El-Shabrawi MHF, Kusmic C, Mizuguchi T S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

Contributor Information

Marcello Mancini, Institute of Biostructure and Bioimaging, National Research Council, Naples 80145, Italy.

Paul Summers, European Institute of Oncology (IEO) IRCCS, Milan 20141, Italy.

Francesco Faita, Institute of Clinical Physiology (IFC), National Research Council (CNR), Pisa 56124, Italy.

Maurizia R Brunetto, Hepatology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University Hospital of Pisa, Pisa 56125, Italy.

Francesco Callea, Department of Pathology, Children Hospital Bambino Gesù IRCCS, Rome 00165, Italy.

Andrea De Nicola, ASL 2 Abruzzo, Policlinico SS Annunziata, Chieti 66100, Italy.

Nicole Di Lascio, Institute of Clinical Physiology (IFC), National Research Council (CNR), Pisa 56124, Italy.

Fabio Farinati, Department of Gastroenterology, Oncology and Surgical Sciences, University of Padua, Padua 35121, Italy.

Amalia Gastaldelli, Cardio-metabolic Risk Laboratory, Institute of Clinical Physiology (IFC), National Research Council (CNR), Pisa 56124, Italy.

Bruno Gridelli, Institute for Health, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), Chianciano Terme 53042, Italy.

Peppino Mirabelli, IRCCS SDN SpA, Naples 80143, Italy.

Emanuele Neri, Diagnostic Radiology 3, Department of Translational Research, University of Pisa and “Ospedale S. Chiara” AOUP, Pisa 56126, Italy.

Piero A Salvadori, Institute of Clinical Physiology (IFC), National Research Council (CNR), Pisa 56124, Italy.

Eleni Rebelos, Hepatology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University Hospital of Pisa, Pisa 56125, Italy.

Claudio Tiribelli, Fondazione Italiana Fegato (FIF), Area Science Park, Campus Basovizza, Trieste 34012, Italy.

Luca Valenti, Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Università degli Studi di Milano and Department of Internal Medicine and Metabolic Diseases, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Policlinico, Milan 20122, Italy.

Marco Salvatore, IRCCS SDN SpA, Naples 80143, Italy.

Ferruccio Bonino, Institute of Biostructure and Bioimaging, National Research Council, Naples 80145, Italy; Institute for Health, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), Chianciano Terme 53042, Italy; Fondazione Italiana Fegato (FIF), Area Science Park, Campus Basovizza, Trieste 34012, Italy.

References

- 1.Morgagni GB. Founders of Modern Medicine: Giovanni Battista Morgagni. (1682-1771) Med Library Hist J. 1903;1:270–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menghini G. One-second needle biopsy of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1958;35:190–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, Gombert S, Giral P, Bruckert E, Grimaldi A, Capron F, Poynard T; LIDO Study Group. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, Berglund A, Eschrich SA, Schabath MB, Forster K, Aerts HJ, Dekker A, Fenstermacher D, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1234–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parmar C, Rios Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Jermoumi M, Carvalho S, Mak RH, Mitra S, Shankar BU, Kikinis R, Haibe-Kains B, et al. Robust Radiomics feature quantification using semiautomatic volumetric segmentation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echegaray S, Nair V, Kadoch M, Leung A, Rubin D, Gevaert O, Napel S. A Rapid Segmentation-Insensitive “Digital Biopsy” Method for Radiomic Feature Extraction: Method and Pilot Study Using CT Images of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Tomography. 2016;2:283–294. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2016.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madabhushi A, Agner S, Basavanhally A, Doyle S, Lee G. Computer-aided prognosis: predicting patient and disease outcome via quantitative fusion of multi-scale, multi-modal data. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2011;35:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu Y, Kumar V, Hall LO, Goldgof DB, Li CY, Korn R, Bendtsen C, Velazquez ER, Dekker A, Aerts H, et al. Automated Delineation of Lung Tumors from CT Images Using a Single Click Ensemble Segmentation Approach. Pattern Recognit. 2013;46:692–702. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmar C, Grossmann P, Bussink J, Lambin P, Aerts HJ. Machine Learning methods for Quantitative Radiomic Biomarkers. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13087. doi: 10.1038/srep13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horsch K, Giger ML, Venta LA, Vyborny CJ. Automatic segmentation of breast lesions on ultrasound. Med Phys. 2001;28:1652–1659. doi: 10.1118/1.1386426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermoye L, Laamari-Azjal I, Cao Z, Annet L, Lerut J, Dawant BM, Van Beers BE. Liver segmentation in living liver transplant donors: comparison of semiautomatic and manual methods. Radiology. 2005;234:171–178. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341031801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Tian J, Xiang D, Li X, Deng K. Interactive liver tumor segmentation from ct scans using support vector classification with watershed. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:6005–6008. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6091484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itakura H, Achrol AS, Mitchell LA, Loya JJ, Liu T, Westbroek EM, Feroze AH, Rodriguez S, Echegaray S, Azad TD, et al. Magnetic resonance image features identify glioblastoma phenotypic subtypes with distinct molecular pathway activities. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:303ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevaert O, Xu J, Hoang CD, Leung AN, Xu Y, Quon A, Rubin DL, Napel S, Plevritis SK. Non-small cell lung cancer: identifying prognostic imaging biomarkers by leveraging public gene expression microarray data--methods and preliminary results. Radiology. 2012;264:387–396. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmar C, Leijenaar RT, Grossmann P, Rios Velazquez E, Bussink J, Rietveld D, Rietbergen MM, Haibe-Kains B, Lambin P, Aerts HJ. Radiomic feature clusters and prognostic signatures specific for Lung and Head & Neck cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11044. doi: 10.1038/srep11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan HP, Doi K, Galhotra S, Vyborny CJ, MacMahon H, Jokich PM. Image feature analysis and computer-aided diagnosis in digital radiography. I. Automated detection of microcalcifications in mammography. Med Phys. 1987;14:538–548. doi: 10.1118/1.596065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Carvalho S, van Stiphout RG, Granton P, Zegers CM, Gillies R, Boellard R, Dekker A, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petta S, Valenti L, Bugianesi E, Targher G, Bellentani S, Bonino F; Special Interest Group on Personalised Hepatology of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF); Special Interest Group on Personalised Hepatology of Italian Association for Study of Liver AISF. A “systems medicine” approach to the study of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF) AISF position paper on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Updates and future directions. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.01.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y, Harano Y, Fujii K, Nakajima T, Kato T, Takeda N, Okuda J, Ida K, et al. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2708–2715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirabelli P, Incoronato MR, Coppola L, Infante T, Parente CA, Nicolai E, Soricelli A, Salvatore M. Bioresource of Human Samples Associated with Functional and/or Morphological Bioimaging Results for the Study of Oncological, Cardiological, Neurological, and Metabolic Diseases. Open Journal of Bioresources. 2017;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Napel S, Giger M. Special Section Guest Editorial:Radiomics and Imaging Genomics: Quantitative Imaging for Precision Medicine. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2015;2:041001. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.2.4.041001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doi K. Computer-aided diagnosis in medical imaging: historical review, current status and future potential. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2007;31:198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM, Piechnik SK, Sarania N, Philips R, Collier JD, Booth JC, Schneider JE, Wang LM, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherry SR. In vivo molecular and genomic imaging: new challenges for imaging physics. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:R13–R48. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/3/r01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlides M, Banerjee R, Sellwood J, Kelly CJ, Robson MD, Booth JC, Collier J, Neubauer S, Barnes E. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging predicts clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iverson SJ, Lang SL, Cooper MH. Comparison of the Bligh and Dyer and Folch methods for total lipid determination in a broad range of marine tissue. Lipids. 2001;36:1283–1287. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohte AE, de Niet A, Jansen L, Bipat S, Nederveen AJ, Verheij J, Terpstra V, Sinkus R, van Nieuwkerk KM, de Knegt RJ, et al. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis: a comparison of ultrasound-based transient elastography and MR elastography in patients with viral hepatitis B and C. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:638–648. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abenavoli L, Beaugrand M. Transient elastography in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robic MA, Procopet B, Métivier S, Péron JM, Selves J, Vinel JP, Bureau C. Liver stiffness accurately predicts portal hypertension related complications in patients with chronic liver disease: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassinotto C, Lapuyade B, Mouries A, Hiriart JB, Vergniol J, Gaye D, Castain C, Le Bail B, Chermak F, Foucher J, et al. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis with impulse elastography: comparison of Supersonic Shear Imaging with ARFI and FibroScan®. J Hepatol. 2014;61:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asrani SK, Talwalkar JA, Kamath PS, Shah VH, Saracino G, Jennings L, Gross JB, Venkatesh S, Ehman RL. Role of magnetic resonance elastography in compensated and decompensated liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coco B, Oliveri F, Maina AM, Ciccorossi P, Sacco R, Colombatto P, Bonino F, Brunetto MR. Transient elastography: a new surrogate marker of liver fibrosis influenced by major changes of transaminases. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:360–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonino F, Arena U, Brunetto MR, Coco B, Fraquelli M, Oliveri F, Pinzani M, Prati D, Rigamonti C, Vizzuti F; Liver Stiffness Study Group ‘Elastica’ of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. Liver stiffness, a non-invasive marker of liver disease: a core study group report. Antivir Ther. 2010;15 Suppl 3:69–78. doi: 10.3851/IMP1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castéra L, Foucher J, Bernard PH, Carvalho F, Allaix D, Merrouche W, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V. Pitfalls of liver stiffness measurement: a 5-year prospective study of 13,369 examinations. Hepatology. 2010;51:828–835. doi: 10.1002/hep.23425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nascimbeni F, Lebray P, Fedchuk L, Oliveira CP, Alvares-da-Silva MR, Varault A, Ingiliz P, Ngo Y, de Torres M, Munteanu M, et al. Significant variations in elastometry measurements made within short-term in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:763–71.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee MS, Bae JM, Joo SK, Woo H, Lee DH, Jung YJ, Kim BG, Lee KL, Kim W. Prospective comparison among transient elastography, supersonic shear imaging, and ARFI imaging for predicting fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichikawa S, Motosugi U, Morisaka H, Sano K, Ichikawa T, Tatsumi A, Enomoto N, Matsuda M, Fujii H, Onishi H. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracies of magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography for hepatic fibrosis. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Bettencourt R, Ramirez K, Fortney L, Hooker J, Sy E, Savides MT, Alquiraish MH, et al. Magnetic Resonance Elastography vs Transient Elastography in Detection of Fibrosis and Noninvasive Measurement of Steatosis in Patients With Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:598–607.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dulai PS, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. MRI and MRE for non-invasive quantitative assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD and NASH: Clinical trials to clinical practice. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1006–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoad CL, Palaniyappan N, Kaye P, Chernova Y, James MW, Costigan C, Austin A, Marciani L, Gowland PA, Guha IN, et al. A study of T1 relaxation time as a measure of liver fibrosis and the influence of confounding histological factors. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:706–714. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heye T, Yang SR, Bock M, Brost S, Weigand K, Longerich T, Kauczor HU, Hosch W. MR relaxometry of the liver: significant elevation of T1 relaxation time in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1224–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torok NJ, Dranoff JA, Schuppan D, Friedman SL. Strategies and endpoints of antifibrotic drug trials: Summary and recommendations from the AASLD Emerging Trends Conference, Chicago, June 2014. Hepatology. 2015;62:627–634. doi: 10.1002/hep.27720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gandon Y, Olivié D, Guyader D, Aubé C, Oberti F, Sebille V, Deugnier Y. Non-invasive assessment of hepatic iron stores by MRI. Lancet. 2004;363:357–362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative Assessment of Liver Fat with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:spcone. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Longo R, Pollesello P, Ricci C, Masutti F, Kvam BJ, Bercich L, Crocè LS, Grigolato P, Paoletti S, de Bernard B. Proton MR spectroscopy in quantitative in vivo determination of fat content in human liver steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5:281–285. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qayyum A. MR spectroscopy of the liver: principles and clinical applications. Radiographics. 2009;29:1653–1664. doi: 10.1148/rg.296095520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon WT. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1984;153:189–194. doi: 10.1148/radiology.153.1.6089263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu H, McKenzie CA, Shimakawa A, Vu AT, Brau AC, Beatty PJ, Pineda AR, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Multiecho reconstruction for simultaneous water-fat decomposition and T2* estimation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bydder M, Yokoo T, Hamilton G, Middleton MS, Chavez AD, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE, Sirlin CB. Relaxation effects in the quantification of fat using gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chebrolu VV, Hines CD, Yu H, Pineda AR, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Samsonov A, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Independent estimation of T*2 for water and fat for improved accuracy of fat quantification. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:849–857. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horng DE, Hernando D, Hines CD, Reeder SB. Comparison of R2* correction methods for accurate fat quantification in fatty liver. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:414–422. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong X, Nickel MD, Kannengiesser SA, Dale BM, Kiefer B, Bashir MR. Liver fat quantification using a multi-step adaptive fitting approach with multi-echo GRE imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:1353–1365. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bashir MR, Zhong X, Nickel MD, Fananapazir G, Kannengiesser SA, Kiefer B, Dale BM. Quantification of hepatic steatosis with a multistep adaptive fitting MRI approach: prospective validation against MR spectroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:297–306. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sofue K, Mileto A, Dale BM, Zhong X, Bashir MR. Interexamination repeatability and spatial heterogeneity of liver iron and fat quantification using MRI-based multistep adaptive fitting algorithm. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:1281–1290. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiménez-Agüero R, Emparanza JI, Beguiristain A, Bujanda L, Alustiza JM, García E, Hijona E, Gallego L, Sánchez-González J, Perugorria MJ, et al. Novel equation to determine the hepatic triglyceride concentration in humans by MRI: diagnosis and monitoring of NAFLD in obese patients before and after bariatric surgery. BMC Med. 2014;12:137. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Middleton MS, Heba ER, Hooker CA, Bashir MR, Fowler KJ, Sandrasegaran K, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Doo E, Van Natta ML, et al. Agreement Between Magnetic Resonance Imaging Proton Density Fat Fraction Measurements and Pathologist-Assigned Steatosis Grades of Liver Biopsies From Adults With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:753–761. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sigrist RMS, Liau J, Kaffas AE, Chammas MC, Willmann JK. Ultrasound Elastography: Review of Techniques and Clinical Applications. Theranostics. 2017;7:1303–1329. doi: 10.7150/thno.18650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mancini M, Prinster A, Annuzzi G, Liuzzi R, Giacco R, Medagli C, Cremone M, Clemente G, Maurea S, Riccardi G, et al. Sonographic hepatic-renal ratio as indicator of hepatic steatosis: comparison with (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metabolism. 2009;58:1724–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xia MF, Yan HM, He WY, Li XM, Li CL, Yao XZ, Li RK, Zeng MS, Gao X. Standardized ultrasound hepatic/renal ratio and hepatic attenuation rate to quantify liver fat content: an improvement method. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:444–452. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edens MA, van Ooijen PM, Post WJ, Haagmans MJ, Kristanto W, Sijens PE, van der Jagt EJ, Stolk RP. Ultrasonography to quantify hepatic fat content: validation by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:2239–2244. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karlas T, Petroff D, Sasso M, Fan JG, Mi YQ, de Lédinghen V, Kumar M, Lupsor-Platon M, Han KH, Cardoso AC, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) technology for assessing steatosis. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1022–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caussy C, Alquiraish MH, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Cepin S, Fortney LE, Ajmera V, Bettencourt R, Collier S, Hooker J, et al. Optimal threshold of controlled attenuation parameter with MRI-PDFF as the gold standard for the detection of hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29639. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Lascio N, Avigo C, Salvati A, Martini N, Ragucci M, Monti S, Prinster A, Chiappino D, Mancini M, D’Elia D, et al. Steato-score: non-invasive quantitative assessment of liver fat by ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018:In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao S, Peng Y, Guo H, Liu W, Gao T, Xu Y, Tang X. Texture analysis and classification of ultrasound liver images. Biomed Mater Eng. 2014;24:1209–1216. doi: 10.3233/BME-130922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Khiyami A, Joseph R, Lopez R, McCullough AJ. Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin CY, Lin WY, Lin CC, Shih CM, Jeng LB, Kao CH: The negative impact of fatty liver on maximum standard uptake value of liver on FDG PET. Clin Imaging. 2011;35:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keramida G, Potts J, Bush J, Verma S, Dizdarevic S, Peters AM. Accumulation of (18)F-FDG in the liver in hepatic steatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:643–648. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abele JT, Fung CI. Effect of hepatic steatosis on liver FDG uptake measured in mean standard uptake values. Radiology. 2010;254:917–924. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Keyes JW Jr. SUV: standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boellaard R. Standards for PET image acquisition and quantitative data analysis. J Nucl Med. 2009;50 Suppl 1:11s–20s. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee HJ, Lee CH, Kim S, Hwang SY, Hong HC, Choi HY, Chung HS, Yoo HJ, Seo JA, Kim SG, et al. Association between vascular inflammation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Analysis by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Metabolism. 2017;67:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dimitriu-Leen AC, Scholte AJHA. Hepatic FDG uptake in patients with NAFLD: An important prognostic factor for cardio-cerebrovascular events? J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:900–902. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0380-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moon SH, Hong SP, Cho YS, Noh TS, Choi JY, Kim BT, Lee KH. Hepatic FDG uptake is associated with future cardiovascular events in asymptomatic individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:892–899. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0297-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Borra R, Lautamäki R, Parkkola R, Komu M, Sijens PE, Hällsten K, Bergman J, Iozzo P, Nuutila P. Inverse association between liver fat content and hepatic glucose uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57:1445–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iozzo P, Geisler F, Oikonen V, Mäki M, Takala T, Solin O, Ferrannini E, Knuuti J, Nuutila P. Insulin stimulates liver glucose uptake in humans: an 18F-FDG PET Study. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:682–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Immonen H, Hannukainen JC, Kudomi N, Pihlajamäki J, Saunavaara V, Laine J, Salminen P, Lehtimäki T, Pham T, Iozzo P, et al. Increased Liver Fatty Acid Uptake Is Partly Reversed and Liver Fat Content Normalized After Bariatric Surgery. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:368–371. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iozzo P, Bucci M, Roivainen A, Någren K, Järvisalo MJ, Kiss J, Guiducci L, Fielding B, Naum AG, Borra R, et al. Fatty acid metabolism in the liver, measured by positron emission tomography, is increased in obese individuals. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:846–856, 856.e1-856.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kudomi N, Slimani L, Järvisalo MJ, Kiss J, Lautamäki R, Naum GA, Savunen T, Knuuti J, Iida H, Nuutila P, et al. Non-invasive estimation of hepatic blood perfusion from H2 15O PET images using tissue-derived arterial and portal input functions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1899–1911. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groß C, Steiger K, Sayyed S, Heid I, Feuchtinger A, Walch A, Heß J, Unger K, Zitzelsberger H, Settles M, et al. Model Matters: Differences in Orthotopic Rat Hepatocellular Carcinoma Physiology Determine Therapy Response to Sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4440–4450. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sung PS, Park HL, Yang K, Hwang S, Song MJ, Jang JW, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Yoo IR, Bae SH. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma as a prognostic predictor in patients with sorafenib treatment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:384–391. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han KH, Seo HJ, Lee JD, Choi HJ. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET for hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Liver Int. 2011;31:1144–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siemerink EJ, Mulder NH, Brouwers AH, Hospers GA. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for monitoring response to sorafenib treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2008;13:734–735; author reply 736-737. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tseng JC, Narayanan N, Ho G, Groves K, Delaney J, Bao B, Zhang J, Morin J, Kossodo S, Rajopadhye M, et al. Fluorescence imaging of bombesin and transferrin receptor expression is comparable to 18F-FDG PET in early detection of sorafenib-induced changes in tumor metabolism. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takahashi Y, Sano R, Nakajima T, Kominato Y, Kubo R, Takahashi K, Ohshima N, Hirano T, Kobayashi S, Shimada T, et al. Combination of postmortem mass spectrometry imaging and genetic analysis reveals very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in a case of infant death with liver steatosis. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;244:e34–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Le Naour F, Bralet MP, Debois D, Sandt C, Guettier C, Dumas P, Brunelle A, Laprévote O. Chemical imaging on liver steatosis using synchrotron infrared and ToF-SIMS microspectroscopies. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuo MD, Gollub J, Sirlin CB, Ooi C, Chen X. Radiogenomic analysis to identify imaging phenotypes associated with drug response gene expression programs in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:821–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sørensen L, Nielsen M, Lo P, Ashraf H, Pedersen JH, de Bruijne M. Texture-based analysis of COPD: a data-driven approach. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:70–78. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2164931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vanderbeck S, Bockhorst J, Kleiner D, Komorowski R, Chalasani N, Gawrieh S. Automatic quantification of lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning in non alcoholic fatty liver disease liver biopsies. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:767–775. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Divine MR, Katiyar P, Kohlhofer U, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Pichler BJ, Disselhorst JA. A Population-Based Gaussian Mixture Model Incorporating 18F-FDG PET and Diffusion-Weighted MRI Quantifies Tumor Tissue Classes. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:473–479. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.163972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Messiou C, Orton M, Ang JE, Collins DJ, Morgan VA, Mears D, Castellano I, Papadatos-Pastos D, Brunetto A, Tunariu N, et al. Advanced solid tumors treated with cediranib: comparison of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and CT as markers of vascular activity. Radiology. 2012;265:426–436. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Son JY, Lee HY, Kim JH, Han J, Jeong JY, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, Shim YM. Quantitative CT analysis of pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules for distinguishing invasive adenocarcinoma from non-invasive or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma: the added value of using iodine mapping. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3816-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee J, Kim SH, Kang TW, Song KD, Choi D, Jang KT. Mass-forming Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Diffusion-weighted Imaging as a Preoperative Prognostic Marker. Radiology. 2016;281:119–128. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim KA, Kim MJ, Jeon HM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Ahn SH, Cha SJ, Chung YE. Prediction of microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma: usefulness of peritumoral hypointensity seen on gadoxetate disodium-enhanced hepatobiliary phase images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35:629–634. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miura T, Ban D, Tanaka S, Mogushi K, Kudo A, Matsumura S, Mitsunori Y, Ochiai T, Tanaka H, Tanabe M. Distinct clinicopathological phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma with ethoxybenzyl-magnetic resonance imaging hyperintensity: association with gene expression signature. Am J Surg. 2015;210:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhou Y, He L, Huang Y, Chen S, Wu P, Ye W, Liu Z, Liang C. CT-based radiomics signature: a potential biomarker for preoperative prediction of early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:1695–1704. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]