Abstract

The Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) provided funding to 29 grantees to increase colorectal cancer screening. We describe the screening promotion costs of CRCCP grantees to evaluate the extent to which the program model resulted in the use of funding to support interventions recommended by the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide). We analyzed expenditures for screening promotion for the first three years of the CRCCP to assess cost per promotion strategy, and estimated the cost per person screened at the state level based on various projected increases in screening rates. All grantees engaged in small media activities and more than 90% used either client reminders, provider assessment and feedback, or patient navigation. Based on all expenditures, projected cost per eligible person screened for a 1%, 5%, and 10% increase in state-level screening proportions are $172, $34, and $17, respectively. CRCCP grantees expended the majority of their funding on Community Guide recommended screening promotion strategies but about a third was spent on other interventions. Based on this finding, future CRC programs should be provided with targeted education and information on evidence-based strategies, rather than broad based recommendations, to ensure that program funds are expended mainly on evidence-based interventions.

Keywords: Program cost, Activity-based costing, Economic evaluation, Colorectal cancer screening

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer related mortality in the United States and poses a significant burden in terms of health outcomes and cost (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2015). Screenings using either fecal occult blood tests, sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies are cost-effective approaches and can lead to the identification of early stage disease when treatments are most effective (Levin et al., 2008; Rex et al., 2009; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2008). However, CRC screening rates are relatively low with some states reporting rates as low as 55% (CDC, 2010, 2013).

Systematic reviews have identified barriers to CRC screening including low levels of education, language or communication issues, low socioeconomic status, lack of insurance coverage, and general attitudes towards prevention (for example, smokers are less likely to seek screening) (Gimeno Garcia, 2012; Subramanian et al., 2004). Through the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP), initiated in 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided grant funding to 25 states and 4 tribal organizations to increase CRC screening (Joseph, DeGroff, Hayes, Wong, & Plescia, 2011). The CRCCP’s goal was to increase CRC screening rates among men and women aged 50–75 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Grantees used their funds to implement population-based promotion activities (screening promotion) and to deliver direct clinical screening services for low income uninsured individuals (screening provision). Additional details on the CRCCP and the grantees are reported elsewhere (Tangka & Subramanian, under review).

Based on systematic literature reviews, the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide) recommends several client-oriented evidence-based strategies to increase CRC screening including client reminders, one-on-one patient education, provider reminders, provider assessment and feedback, small media, and efforts to reduce structural barriers, including the use of patient navigation (Sabatino et al., 2012; The Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2013). A key goal of the CRCCP is to foster the use of evidence-based screening promotion interventions as these strategies are more likely to lead to efficient use of resources than strategies with limited evidence. A prior study had indicated that CRCCP grantees are more likely to adopt and implement evidence-based interventions recommended by the Community Guide than non-grantees (Hannon et al., 2013) but no study to date has assessed the proportion of the funding devoted to evidence-based strategies.

The objective of this study is to quantify the allocation of resources to each type of promotion activity implemented by the CRCCP grantees and to evaluate the extent to which expenditures supported Community Guide-recommended interventions. We analyzed data from the first three years of the CRCCP focusing only on the screening promotion component. In addition, since we are unable to isolate the impact of the CRCCP on screening rates in all sites given that factors beyond the program influence population-level screening rates, we estimated cost per case based on various anticipated scenario-based increases in screening use. This information will be used to guide future CRC program implementation by providing target screening goals that have to be reached to ensure cost-effective program activities.

2. Methods

2.1. Cost data collection

A web-based cost assessment tool (CRCCP web-CAT) was developed to collect information from CRCCP-funded grantees on their program activities and expenditures (Subramanian, Bobashev, & Morris, 2010). The CAT is based on well-established methods of collecting cost data for program evaluation (Anderson, Bowland, Cartwright, & Bassin, 1998; Drummond, Schulpher, Torrance, O’Brien, & Stoddard, 2005; French, Dunlap, Zarkin, McGeary, & McLellan, 1997; Salome, French, Miller, & McLellan, 2003). Details on developing, testing and evaluating the CAT have been published (Subramanian, Ekwueme, Gardner, & Trogdon, 2009). Staff from 29 CRCCP-funded grantees completed the web-CAT on an annual basis beginning in 2009 for three years (July 2009–June 2012). Three of the grantees (Nevada, Georgia and Michigan) were not funded in the first year of the CRCCP but were funded in years 2 and 3 and are included in the analysis.

Using the CRCCP web-CAT, grantees reported on the following budget categories: staff salaries, contract expenditures, purchases of materials and equipment, and administration or overhead costs, such as telephone and rent. To appropriately allocate the expenditures, the CRCCP web-CAT captured details on the distribution of both labor and non-labor costs, including in-kind contributions, for all activities performed. Program staff then allocated costs to various screening promotion activities (for example, client reminders, and provider feedback and assessment), screening provision activities, and overall programmatic activities such as program management, partnership development and administration (see Table 1). Overall, approximately $87 million were expended by the CRCCP grantees over three years with 49% of these funds allocated to screening promotion activities (screening promotion activities are reported in a companion manuscript).

Table 1.

Summary of the Screening Promotion, Screening Provision, and Overarching Components Activities of the CRCCP.

| Screening Promotion Activities | Screening Provision Activities | Overarching Componentsb Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Client Remindersa | Provider contracts, billing systems, other billing procedures | Program Management |

| Small Mediaa Provider Assessment and Feedbacka Provider Remindersa Reduction in Structural Barriersa (including patient navigation) Mass Media Reduction in Out-of-Pocket Support Enrolling in Insurance Programs Other Promotion Activities |

Patient navigation and support Screening and diagnostic services (only labor, if any are reported) Ensure cancer treatment Other screening provision activities Screening and diagnostic services (only clinical) Screening & diagnosis Surveillance |

Quality Assurance/Professional Development Partnership Development and Maintenance Clinical and Cost Data Collection and Tracking Program Monitoring and Evaluation Administration Other Activities |

Strategies recommended by the Guide to Community Preventive Services for increases colorectal cancer screening compliance using FOBT.

Overarching components relate to both screening promotion and screening provision activities.

Several features were implemented to ensure data collection methods were standardized across all grantees, including web-based trainings for users, a user’s guide, and ongoing technical assistance. To ensure high-quality, error-free data, the CRCCP web-CAT included a series of automated data checks. Finally, grantees reviewed and approved data summaries that were prepared after systematic edits were applied.

2.2. Activity-based cost estimation

We estimated labor costs using the following information: (1) the number of hours worked by staff per month on various activities, (2) the proportion of staff salaries paid through CRCCP funds, (3) the percentage of time that staff members worked, and (4) staff salaries. We computed the hourly rate for each staff member and used the hours spent on each program activity to allocate parts of the total salary to the activities performed. We then aggregated the labor costs for each activity and assigned in-kind labor contributions to each program activity. Similarly, we aggregated the costs of consultants, materials, equipment and supplies for each activity, and derived the total overhead costs related to the program by utilizing detailed information provided by the grantees on rent, utility payments, and other indirect costs. All labor and non-labor costs were assigned to the specific activities performed by the grantees as reported in Table 1.

2.3. Data analysis

For the present analyses, costs were aggregated and analyzed for screening promotion activities across all programs for the three–year time period (see Table 1). We also examined costs by dividing grantees into high, mid, and low screening promotion expenditure based on percentiles (<34th, 34th- 66th, >66th percentiles). The average expenditure for each of these three groups was $424,178, $710,346 and $1,411,918, respectively.

Lastly, we estimated the cost per person screened based on various hypothetical increases in population-level screening rates; that is, we used the following methods to estimate the projected promotion cost per case based on anticipated increases in screening rates. We utilized aggregated screening promotion costs from the CRCCP web-CAT, and 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System state-based, combined CRC screening rates (based on multiple tests) to assess screening prevalence at the start of the CRCCP, and population counts for grantee states (we did not include tribal organizations in this calculation) from the 2012 American Community Survey to calculate the number of people eligible for CRC screening (50–75 year olds). We used the 2012 estimates because the changes implemented in the survey methodology makes it more comparable to future data and because the overall impact of the CRCCP will likely occur over the long term as the majority of eligible individuals in the United States are screened with colonoscopy for which prevalence is reported over the previous 10-year period. We calculated the cost of promotion activities per person screened using hypothetical projected increases in screening rates in the eligible population of 1%, 5%, and 10% due to promotion activities. We assumed all states would experience similar rates of increased screening compliance and did not adjust for potential differences between states.

We did not adjust the 3 years of data for cost-of-living differences across geographic areas because our objective was to assess distribution of cost across promotion activities and the benefits for each specific grantee separately and then compare percentage distributions across grantees. We were unable to allocate approximately 10% of the screening promotion expenditures as these were either lump sum payments made to subcontracted organizations for multiple activities (all related to promotion) or the grantees were not able to allocate them to specific promotion activities. In addition, we were unable to systematically separate all programmatic and direct cost components for three grantees. We excluded these costs from the analysis on the distribution of screening promotion activities or programmatic costs, but they were retained in total cost and cost per person screened assessments. This study was reviewed and considered exempt by the RTI International Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

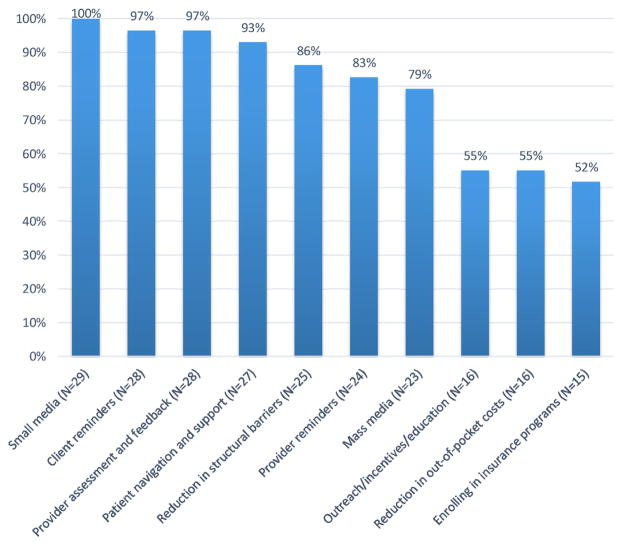

Fig. 1 presents the proportion of grantees that expended funds for each screening promotion strategy during the first three years of the CRCCP. All 29 grantees used funds for small media and more than 90% used funds for client reminders, provider assessment and feedback, and/or patient navigation. About 80% of the grantees expended funds for activities to remove structural barriers, implementing provider reminders, and/or mass media campaigns. Only half the grantees used funds to conduct patient outreach/incentives/education, reduction in out-of-pocket costs, and/or enrollment in insurance program, specifically Medicaid.

Fig. 1.

Percent of CRCCP Grantees Reporting Costs for Specific Screening Promotion Activities, 2009–2012.

For the three year period, the average total cost of screening promotion (including in-kind costs) across the grantees was $1,256,012. The average cost of direct screening promotion activities was $809,474 with an additional average expenditure of $446,538 for other overarching programmatic activities related to the promotion approaches. Therefore, the screening promotion activities themselves accounted for about 65% of the total promotion costs and the remaining 35% was related to supporting programmatic activities such as program management and partnership development.

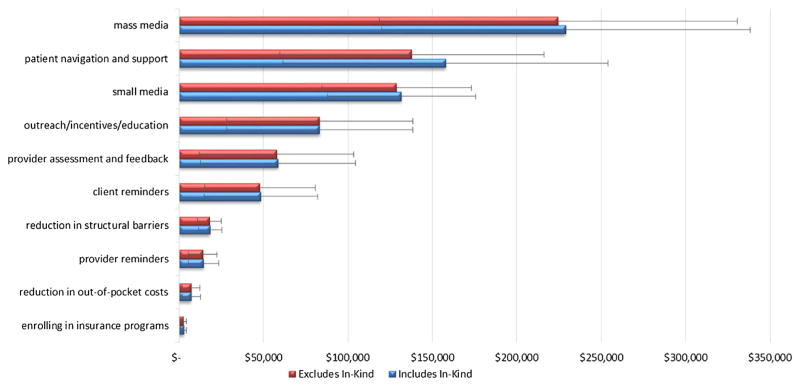

Fig. 2 displays the average aggregate cost of screening promotion activities across all grantees over the three-year period in dollar amount and percent distribution; the statistics are reported with and without in-kind contributions. Mass media comprised the largest screening promotion category in terms of cost. Without considering in-kind contributions, on average, across all 29 grantees, mass media accounted for approximately $225,000, or 31%, of grantees’ direct screening promotion expenditure (percent of average proportion data not shown in the figure). This was followed by patient navigation and support ($137,868) and small media ($128,859), with grantees reporting spending 19% and 18% of their screening promotion expenditures on these activities, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Overall Average Cost of CRCCP Grantees’ Screening Promotion Activities Across all Grantees for the 3-year period, Including and Excluding In-kind Contributions (whiskers indicate 95% CIs).

Notes: When the two bars are equal, there were no in-kind contributions reported for that particular cost activity.

Outreach/incentives/education ($83,226), provider assessment and feedback ($57,731), and client reminders ($47,891) accounted for between 7% and 12% of the screening promotion expenditures. Grantees spent 3% or less on each of the following categories: reducing structural barriers (such as reducing time or distance between service delivery settings and target populations) and out-of-pocket costs, provider reminders, and enrolling participants in insurance programs. In-kind contributions (Fig. 2) were most often provided to support patient navigation activities initiated by the grantees and the average amount of the contribution was about $20,000 (15% of the navigation cost).

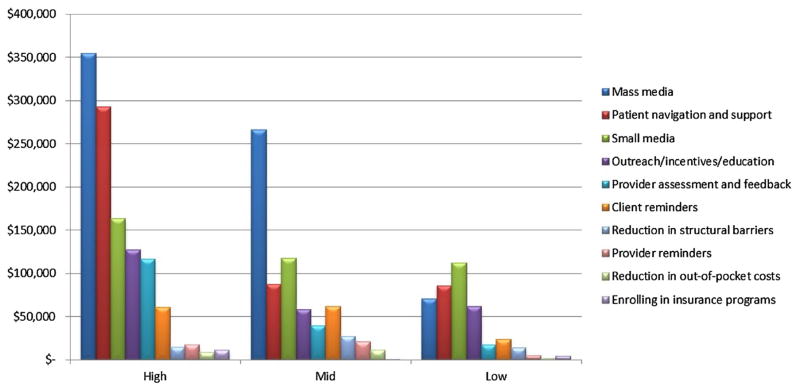

Fig. 3 presents average cost stratified by the screening promotion expenditure of the grantees, separated into three groups: low (n = 10), medium (n = 9) and high expenditures (n = 10) (the distributions were 33rd percentile or less, 34th-66th percentile, 67th percentile or higher). The high and mid-range grantees, based on total funds that include in-kind contributions, spent the largest proportion of their funds on mass media, while grantees with lower funding allocated the largest proportion to small media. There was large variation in spending on mass media while there was a much smaller difference in dollar amount on funds allocated to small media. Grantees with the largest awarded funding spent three times more on patient navigation and support when compared to grantees with mid-range and low funding (approximately $300,000 compared to about $85,000 on average). Nevertheless, across the high, medium and low funded grantees, mass media, small media and patient navigation represented the top three cost expenditure activities.

Fig. 3.

Overall Average Cost of CRCCP Grantees’ Screening Promotion Activities for the Highest, Middle and Lowest Third of Sites, Dollar Distribution, 2009–2012. Note: We also examined costs by dividing grantees into high, mid, and low screening promotion expenditure based on percentiles: high = >66th percentile; mid = 34th–66th percentile; low = <34th percentile. There were 10 grantees in the high-expenditure and low-expenditure groups; there were 9 grantees in the medium-expenditure group.

Table 2 presents the cost per person screened based on hypothetical scenarios of increases in state-level screening rates of 1%, 5% and 10%. On average, a 1% increase in screening rates across the grantee states over the 3-year period would cost $172 per person screened; a 5% increase would cost $34 and a 10% increase would cost $17. We also provide the distribution of the promotion cost per person screened across the grantees. For example, if there was a 1% increase in screening rates, 72% of the grantees would incur cost of less than $200 per person while only 4% of grantees would incur cost less than $10 per person screened. Alternatively, with a 5% increase in screening rates, 96% would have cost less than $100 per person screened. With a 10% increase, nearly all programs (96%) would have cost less than $50 per person screened and nearly half (48%) would have cost less than $10 per person screened.

Table 2.

Estimated Cost of Screening Promotion Activities Per Eligible Person Screened based on Hypothetical Scenarios of Increases in State Level Screening Rates.

| Cost per case

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% increase: | 5% increase: | 10% increase: | |

| Mean | $177.13 (±75.43) | $35.43 (±15.08) | $17.71 (±7.54) |

| Range | $7.33–$881.02 | $1.47–$176.20 | $0.73–$88.10 |

| % under $10 | 4 | 24 | 48 |

| % under $50 | 24 | 72 | 96 |

| % under $100 | 48 | 96 | 100 |

| % under $200 | 72 | 100 | 100 |

Sources: BRFSS 2012; ACS 2012; CAT 2009–2912.

Notes:

For example, if there was a 1% increase in screening rates, 72% of the grantees would incur cost of less than $200 per person while only 4% of grantees would incur cost less than $10 per person screened.

The purpose of the CRCCP is to promote colorectal cancer (CRC) screening to increase population-level screening rates and, subsequently, to reduce CRC incidence and mortality.

In 2012 the national screening rate was 65.5% (65.1–65.9), and the grantee screening rate was 67.5% (66.9–68.1) (BRFSS 2012).

4. Discussion

In this study, we provide information on the costs associated with screening promotion activities at the program level and projected cost per person screened among 29 CRCCP grantees. The key finding is that the majority of screening promotion funding was expended on client and provider oriented evidence-based approaches that were recommended by the Community Guide. Patient navigation and small media were among the client-based approaches that received the largest amount of funding; approximately $130,000 each over the first 3 years of the program. Provider assessment and feedback were the most common provider-oriented approach with an average of $58,000 expended across all grantees. The largest allocation of $225,000 was expended on mass media campaigns for which the Community Guide found insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness because of the paucity of studies. Therefore, although the CRCCP was largely able to influence grantees to use evidence-based strategies, additional policies will be required to ensure the consistent use of recommended interventions.

Additionally, our assessment of the average distribution of funds on promotion approaches selected by grantees with high, medium and low levels of funding identified some similarities and differences that can inform future program planning. Grantees with lowest level of funding directed a higher proportion of the available funds to evidence-based approaches of small media campaigns and patient navigation, while high and mid-level funded grantees spent the largest amount on mass media campaigns. It is possible that those with higher levels of funding had the resources required to plan and implement mass media campaigns, which are generally quite expensive (advertisements on TV/radio or billboards require substantial investment of resources). Nevertheless, all grantees, regardless of the size of the funding available, spent the most on three activities: small media, mass media and patient navigation. Additional research is needed to identify the optimal mix of screening promotion approaches to maximize impact on cancer screening at a population-level.

Across all CRCCP grantees, approximately 35% of total promotion cost, including in-kind contributions, was incurred in performing indirect, overarching programmatic activities. The support activities can play a very important and necessary role in ensuring efficient management of promotion activities and also ensure coordination with partners and collaborators (Tangka et al., 2008). These programmatic costs are therefore a critical component and should be accounted for in future program budgets. The proportion of cost required for these support activities may actually be lower than those incurred by the CRCCP grantees, given the grantees may have expended additional resources to start-up the screening promotion activities and meet specific data collection and reporting tasks. In addition, prior studies of cancer programs have shown that these programmatic costs have significant economies of scale and, as program increase in size, the programmatic cost per person serves decreases substantially (Subramanian, Ekwueme, Gardner, Bapat, & Kramer, 2008; Trogdon, Ekwueme, Subramanian, & Crouse, 2014).

The overall goal of the CRCCP is to increase the CRC screening rate among men and women aged 50–75 years. Three years into the first 6-year cycle of the program, a hypothetical 5% and 10% increase in compliance would have resulted in a screening promotion cost per person of under $100 and $50 respectively. Studies have shown that evidence-based promotion activities can increase screening utilization (Ladabaum, Mannalithara, Jandorf, & Itzkowitz, 2015; Pinkowish, 2009; Sabatino et al., 2012; Wilson, Villarreal, Stimpson, & Pagan, 2015) but the design of the CRCCP promotion interventions did not allow for program impacts to be assessed independent of overall state population level impacts. The findings from this study can therefore assist policy makers to assess the potential cost and benefit of the program and provide effectiveness thresholds to guide future program funding decisions.

Although we took specific steps to ensure that the results would be comparable across the 29 grantees, there were a few limitations. First, the grantees reported their resource use and cost on a retrospective basis each year, and therefore, potential misallocation of resources and errors are possible. We believe any such bias is likely to be minimal as all grantees were informed about the details of the cost data collection for the CRCCP program so that they could prospectively plan by maintaining accurate records. All grantees were also provided technical assistance and clear definitions of the activities to ensure accurate allocation of resources to activities. Second, the grantees differed in the resources expended on specific promotion activities but we did not take this difference into consideration when assessing potential benefit in terms of increasing compliance with CRC screening. In addition, grantees may have targeted different populations with each type of intervention, but we did not have detailed information related to each promotion activity to perform assessment at the intervention level. Future evaluation studies should be performed to assess specific intervention level impacts and provide information on cost-effectiveness to enhance the evidence base provided in the Community Guide (The Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2013). Third, we were unable to fully allocate all direct activities related to screening promotion to specific approaches for some grantees and therefore had to exclude these costs from some of the analyses. This only affected a small number of grantees and the total monetary value was not large and therefore this should not have introduced any systematic bias. Fourth, we included tribal organizations in our analyses but their cost allocation and reporting varied from state programs. Therefore, it is not clear whether the study findings can be extrapolated beyond states to tribes and territories who may implement CRC programs.

5. Conclusions and lessons learned

The findings presented in this study can assist CRCCP grantees, other CRC screening programs, and policy makers to understand programmatic cost, screening promotion cost distribution, and projected cost per person screened to guide future program planning and implementation. Research should be undertaken to understand the optimal mix of screening promotion activities, as a complementary set of approaches may prove to be the most cost-effective combination to increase CRC screening rates. Although the CRCCP was largely successful in fostering the use of evidence-based interventions, future implementation should use targeted approaches that specify interventions rather than broad based recommendations to ensure grantees use strategies recommended by the Community Guide to deliver high-impact programs.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contract Number 200-2008-27958, Task Order 01, to RTI International.

Abbreviations

- CAT

cost assessment tool

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CRCCP

Colorectal Cancer Control Program

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Anderson DW, Bowland BJ, Cartwright WS, Bassin G. Service-level costing of drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening among adults aged 50–75 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Colorectal cancer screening test use—United States, 2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer control program (CRCCP) Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Accessed 6 March 2016]. from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/crccp/ [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, Schulpher M, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddard G. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. England: Publishing, Oxford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Dunlap LJ, Zarkin GA, McGeary KA, McLellan AT. A structured instrument for estimating the economic cost of drug abuse treatment: The drug abuse treatment cost analysis program (DATCAP) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno Garcia AZ. Factors influencing colorectal cancer screening participation. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2012;2012(483417) doi: 10.1155/2012/483417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon PA, Maxwell AE, Escoffery C, Vu T, Kohn M, Leeman J, et al. Colorectal cancer control program grantees’ use of evidence-based interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45:644–648. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph DA, DeGroff AS, Hayes NS, Wong FL, Plescia M. The colorectal cancer control program: Partnering to increase population level screening. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011;73:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Jandorf L, Itzkowitz SH. Cost-effectiveness of patient navigation to increase adherence with screening colonoscopy among minority individuals. Cancer. 2015;121:1088–1097. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American cancer society, the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer, and the American college of radiology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2008;58:130–160. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkowish MD. Promoting colorectal cancer screening: Which interventions work? CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59:215–217. doi: 10.3322/caac.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM, et al. American college of gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104:739–750. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, Mercer SL, Wilson KM, DeVinney B, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical: And colorectal cancers: Nine updated systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43:97–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salome HJ, French MT, Miller M, McLellan AT. Estimating the client costs of addiction treatment: First findings from the client drug abuse treatment cost analysis program (Client DATCAP) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: A review. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:536–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Bapat B, Kramer C. Identifying and controlling for program-level differences in comparative cost analysis: Lessons from the economic evaluation of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2008;31:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Trogdon J. Developing and testing a cost-assessment tool for cancer screening programs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Bobashev G, Morris RJ. When budgets are tight: There are better options than colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening. Health Affairs. 2010;29:1734–1740. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangka F, Subramanian S. Importance of implementation economics for program planning – the case for colorectal cancer control program. 2016. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangka FK, Subramanian S, Bapat B, Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Gardner J, et al. Cost of starting colorectal cancer screening programs: Results from five federally funded demonstration programs. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;5:A47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Cancer prevention and control. Atlanta, GA: The Guide to Community Preventive Services; 2013. [Accessed 6 March 2016]. n.p. from www.thecommunityguide.org/cancer/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Trogdon JG, Ekwueme DU, Subramanian S, Crouse W. Health Care Management Science. 2014;17:321–330. doi: 10.1007/s10729-013-9261-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States cancer statistics: 1999–2012 incidence and mortality. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2015. [Accessed 6 March 2016]. from www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149:627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FA, Villarreal R, Stimpson JP, Pagan JA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a colonoscopy screening navigator program designed for Hispanic men. Journal of Cancer Education. 2015;30:260–267. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]