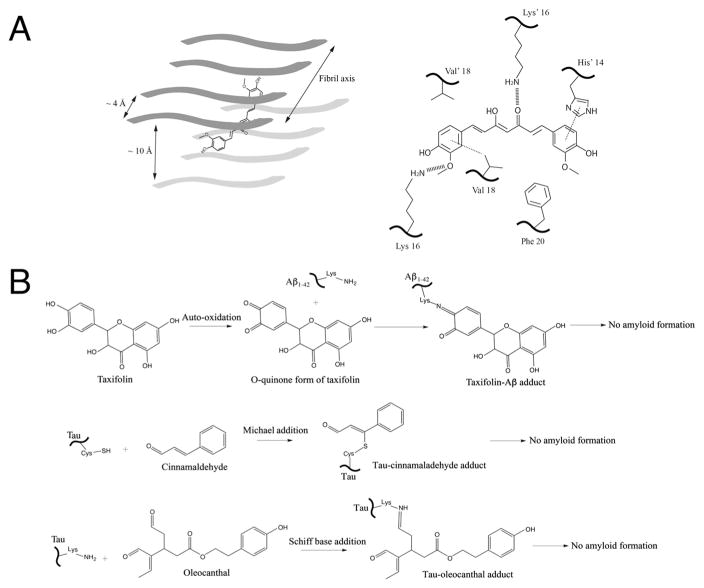

Fig. 2.

Schematic representations of several proposed mechanisms between inhibitors and amyloid proteins. (A) Non-covalent interaction mechanisms with curcumin as an example. Left panel: The planar curcumin molecule is depicted by a cartoon schematic within the cross beta spine of an octomeric fibrillar backbone. This representation is based on the structural model of curcumin bound to the VQIVYK segment from the tau protein as well as MD simulation results of curcumin docking onto Aβ hexapeptide KLVFFA [30]. Right panel: key non-covalent interactions occur within the cross beta spine of full-length amyloid β peptide and curcumin, as depicted from a recent MD simulation study [32]. His14 undergoes π–π stacking (dotted line) with one end of the aromatic heads of curcumin, which is also positioned in a hydrophobic area near Phe20 (bottom right). The central keto-enol functional groups and as well as the aromatic head (bottom left) undergo hydrogen bonding with lysine residues located on opposite sides of the cross beta spine (hashed lines). Additionally, π–alkyl interactions (depicted by dotted line) were seen between the aromatic head of curcumin (bottom left) and Val18 residues. (B) Covalent interaction mechanisms. Small molecule natural compounds containing electrophilic functional groups such as o-quinones and aldehydes form covalent adducts with amyloidogenic proteins and prevent amyloid formation. (Top panel) Taxifolin forms covalent adducts with the side chain amine group of lysine in Aβ1-42 via Schiff base formation via o-quinone intermediates. (Middle and Lower panels) Tau is covalently modified by the aldehyde functional groups in the case of cinnamaldehyde (middle panel) and oleocanthal (lower panel) via Michael addition and Schiff base respectively. Such conjugation prevents protein amyloid growth and formation.