Abstract

Background:

There is a lack of contemporaneous data on the practices of flexible bronchoscopy in India.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to study the prevalent practices of flexible bronchoscopy across India.

Methods:

The “Indian Bronchoscopy Survey” was a 98-question, online survey structured into the following sections: general information, patient preparation and monitoring, sedation and topical anesthesia, procedural/technical aspects, and bronchoscope disinfection/staff protection.

Results:

Responses from 669 bronchoscopists (mean age: 40.2 years, 91.8% adult pulmonologists) were available for analysis. Approximately, 70,000 flexible bronchoscopy examinations had been performed over the preceding year. A majority (59%) of bronchoscopists were performing bronchoscopy without sedation. A large number (45%) of bronchoscopists had learned the procedure outside of their fellowship training. About 55% used anticholinergic premedication either as a routine or occasionally. Nebulized lignocaine was being used by 72%, while 24% utilized transtracheal administration of lignocaine. The most commonly (75%) used concentration of lignocaine was 2%. Midazolam with or without fentanyl was the preferred agent for intravenous sedation. The use of video bronchoscope was common (80.8%). The most common (94%) route for performing bronchoscopy was nasal. Conventional transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) was being performed by 74%, while 92% and 78% performed endobronchial and transbronchial lung biopsy, respectively. Therapeutic airway interventions (stents, electrocautery, cryotherapy, and others) were being performed by 30%, while endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) and rigid bronchoscopy were performed by 27% and 19.5%, respectively.

Conclusion:

There is a wide national variation in the practices of performing flexible bronchoscopy. However, there has been a considerable improvement in bronchoscopy practices compared to previous national surveys.

KEY WORDS: Anesthesia, bronchoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, lung biopsy, transbronchial needle aspiration

INTRODUCTION

Although flexible bronchoscopy was introduced into pulmonology almost 50 years ago,[1] its practice and procedural aspects are yet not standardized. The paucity of technical aspects of bronchoscopy in major bronchoscopy guidelines contributes to local and international differences in practice of bronchoscopy.[2] This is highlighted by comparing the findings of a few recently published bronchoscopy surveys.[3,4] Consequently, the practice of bronchoscopy varies, depending on the physician preferences and the availability of resources. The practice is mostly dependent on the skills being passed on from the preceptor to the trainee, without any systematic teaching and learning methodology.

There exists a significant variation in the methods pertaining to performance of flexible bronchoscopy across India. This was highlighted 12 years ago in a bronchoscopy survey from India (including 149 respondents), akin to the bronchoscopy surveys conducted in other countries.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11] The “Indian Bronchoscopy Survey” was planned to study the existing practices of flexible bronchoscopy across the country and compare the prevalent practices with bronchoscopy surveys conducted in other countries. Herein, we report the results of this survey.

METHODS

The “Indian Bronchoscopy Survey” was an online survey conceptualized and designed in the Department of Pulmonary Medicine and Sleep Disorders at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. The survey included 98 questions [Supplemental File 1], prepared in the English language. The responses were anonymous; no names or personal details including E-mails were required from the respondents. The survey was developed on the “Google Forms” interface. Google Forms is a free-to-use data capturing interface by “Google” that allows easy conduct of surveys.[12] The survey form was structured and divided into various sections that included general information, patient preparation and monitoring, sedation and topical anesthesia, procedural/technical aspects, and bronchoscope disinfection/staff protection. The questions were of either a descriptive response type or multiple option type. The option type questions either had a “Yes/No” response or option for multiple responses. As various procedures are not consistently performed at all the times, options for many questions were specified as “always, most of the times, sometimes, and never,” wherever considered appropriate. Several questions had an option for the respondent to provide additional information if none of the options matched the operator's practice. A trial run was performed wherein the authors responded to the survey themselves and identified areas that needed refinement. The e-mail lists of the three major national bodies of pulmonologists and bronchoscopists were utilized. These included the Indian Association for Bronchology, the Indian Chest Society, and the National College of Chest Physicians of India. As many pulmonologists are members of more than one of these societies, it is likely that many participants received more than one e-mails initially. In addition, e-mails were also sent from personal e-mailing lists of the authors.

The survey protocol was finalized in mid-October 2016 and the first survey e-mail was sent on October 31, 2016. All e-mails were sent within the next 1 week and a reminder e-mail was sent a month later. It was decided to keep the survey link open for the next 3 months to gather the responses. The participation in the survey was voluntary and no financial incentive was offered to the participants for responding.

Statistical analysis

Responses were downloaded as an excel spreadsheet. Responses from only those who were performing bronchoscopy were included in the study. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using STATA Statistical analysis package (Version 11.2), StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA. Categorical variables were presented as number (percentages) and continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range [IQR]).

RESULTS

We received 701 responses, of which 669 respondents were performing flexible bronchoscopy and were included in the study. Majority (75%) of the responses were obtained within the first 3 weeks of the initiation of the survey. Approximately 66,900 bronchoscopies were performed over the preceding 1 year (median 100 procedures/physician/year; IQR, 40–200). We received responses from 155 cities; however, nearly half (313 of the 669 [46.8%]) were from ten cities: Delhi (n = 98), Mumbai (n = 37), Bengaluru (n = 37), Hyderabad (n = 34), Kolkata (n = 22), Chandigarh (n = 19), Bhopal (n = 15), Chennai (n = 14), Jaipur (n = 14), and Coimbatore (n = 13).

General information

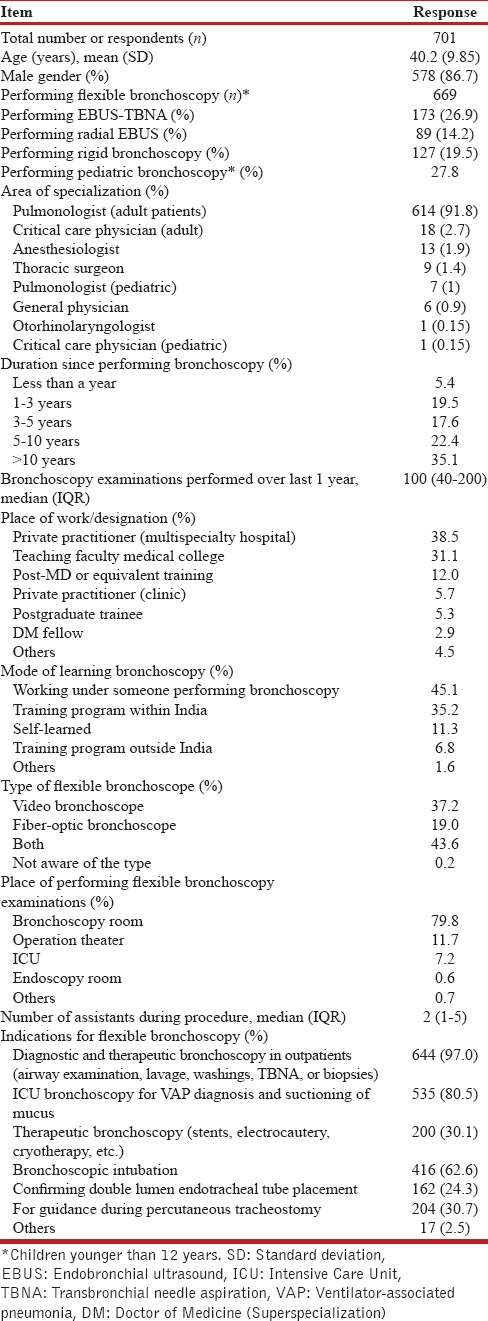

The respondents were predominantly adult pulmonologists (91.8%), mostly male (86.7%), with a mean age of 40.2 years [Table 1]. Most were working in nongovernmental multispecialty hospitals (38.5%) or as teaching faculty in medical colleges (31.1%). About 27.8% were performing bronchoscopy in children younger than 12 years of age. Most (80.8%) were using the video bronchoscopy equipment. A large number (45.1%) had learned bronchoscopy outside their fellowship training. Bronchoscopy was being performed for 5 years or more by 57.5%. A median of two assistants (IQR, 1–5) was available during the procedure, and a bronchoscopy suite/room was the most commonly utilized area (79.8%) for performing the procedure. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was being performed by 26.9%, while 19.5% and 14.2% performed rigid bronchoscopy and radial EBUS, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the survey respondents

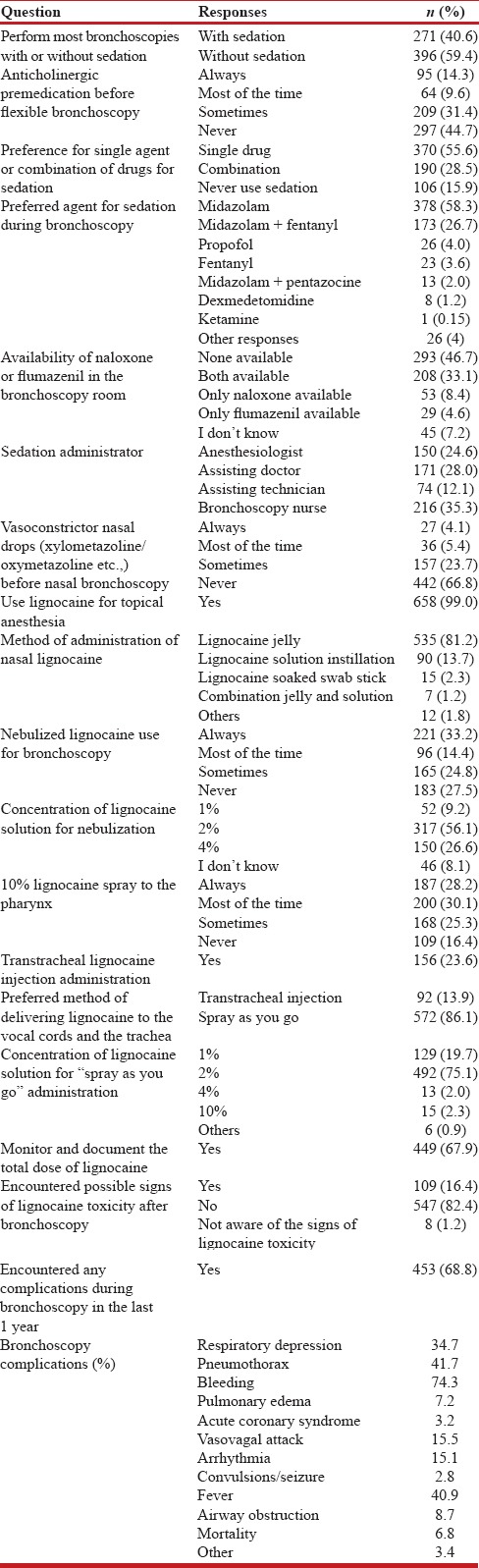

Patient preparation and monitoring details

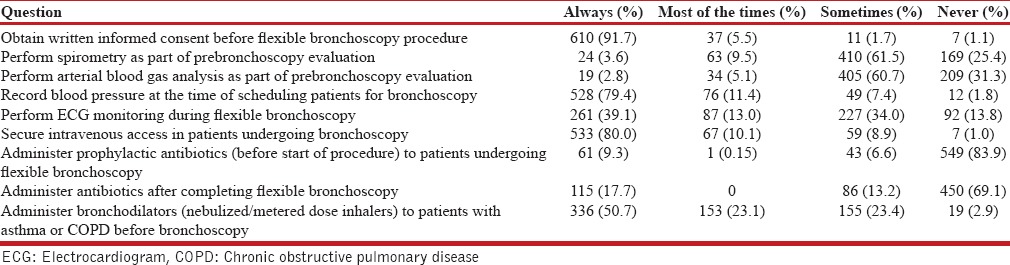

The patient preparation and monitoring details are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. A written informed consent was regularly being obtained by 91.7%. A majority (97.7%) kept the patient fasting before the procedure, of which 72.7% fasted patients for 4–8 h prior. Blood pressure was recorded by 79.4% at the time of scheduling patients for bronchoscopy. An intravenous access was routinely secured by 80%, while 39.1% routinely performed electrocardiogram monitoring during flexible bronchoscopy. Almost all (99.4%) were using pulse oximetry during the procedure and 73% monitored blood pressure during the procedure. Supplemental oxygen was continuously administered during the procedure by 54.2%, while 43.4% gave it only when desaturation occurred. Nasal cannula was the most commonly (69.6%) utilized device for administering oxygen. About 30% did not have the facility of a separate recovery room to monitor the patient following the procedure. Majority (62.6%) of the respondents observed the patient for 1–2 h or longer following bronchoscopy. Coagulation studies were routinely performed by 26.2%, while 44.5% performed them only in patients planned for either endobronchial biopsy (EBB) or transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB). Hemoglobin and platelet counts were obtained by 52.7% and 39.5%, respectively; 35.3% obtained renal function tests as a routine in patients planned for bronchoscopy. Only 53.6% discontinued aspirin or clopidogrel before performing flexible bronchoscopic biopsy.

Table 2.

Patient preparation and monitoring details during flexible bronchoscopy

Table 3.

Patient preparation and monitoring details during flexible bronchoscopy

As part of prebronchoscopy evaluation, 61.5% obtained spirometry, while 60.7% performed arterial blood gas measurement sometimes. Majority (83.9%) would never administer prophylactic antibiotics while a fairly large number (30.9%) were routinely or occasionally administering antibiotics following bronchoscopy. Inhaled bronchodilators administered before beginning the bronchoscopy in patients with obstructive airway diseases were being used as a routine or most of the times by 73.8%.

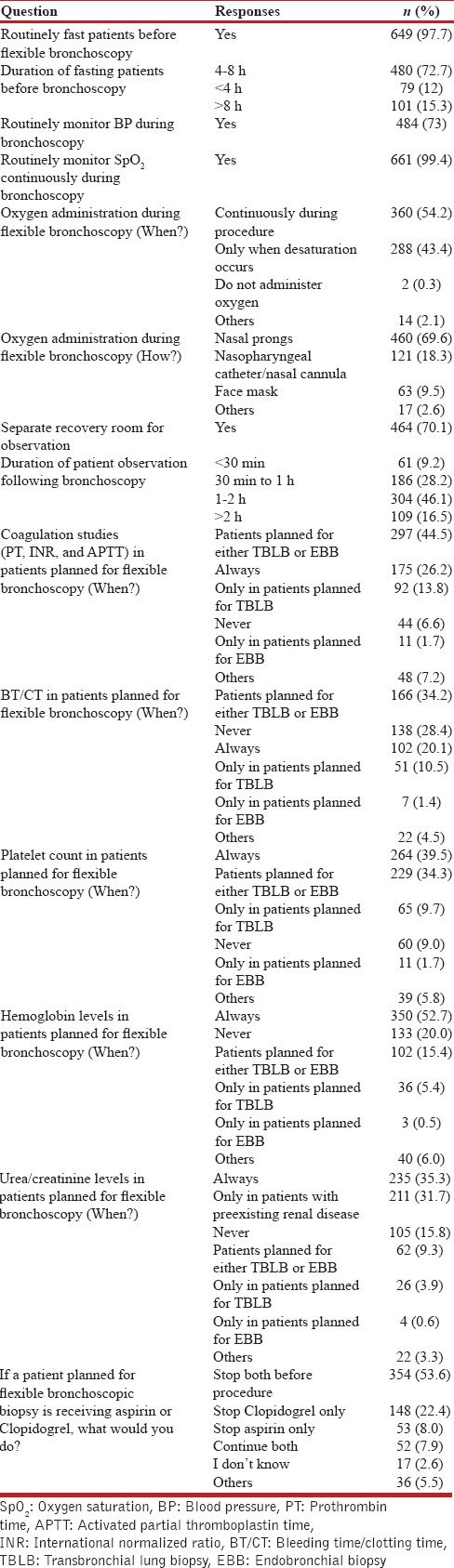

Sedation and topical anesthesia

The details of responses are summarized in Table 4. Bronchoscopy performed only under topical anesthesia and without any conscious sedation was the most common practice (59.4%). Anticholinergic premedication was regularly or occasionally used during bronchoscopy by 55.3%. The use of a single sedative was preferred (55.6%) and midazolam alone (or in combination) was the most commonly used drug (87.0%) for sedation. Either naloxone or flumazenil was not available with 46.7% of the respondents in their bronchoscopy area. An anesthetist was available during the procedure for only 24.6% of the respondents.

Table 4.

Sedation and topical anesthesia during flexible bronchoscopy

Only 33.2% used nasal vasoconstrictors before nasal bronchoscopy. Lignocaine jelly (gel) was the most common method (81.2%) for nasal lignocaine administration. Nebulized lignocaine was used for topical anesthesia either routinely or occasionally by 72.4%. The most commonly (56.1%) used concentration of lignocaine for nebulization was 2%. A large number (83.6%) used 10% lignocaine spray for pharyngeal anesthesia either routinely or occasionally. Transtracheal lignocaine administration was being performed by 23.6%. The preferred method (86.1%) of delivering lignocaine to the vocal cords and the tracheobronchial tree was the spray-as-you-go technique using 2% lignocaine (75.1%). The total lignocaine dose used was documented by only 67.9%. About 68.8% had encountered one or more bronchoscopy-related complications during the previous year.

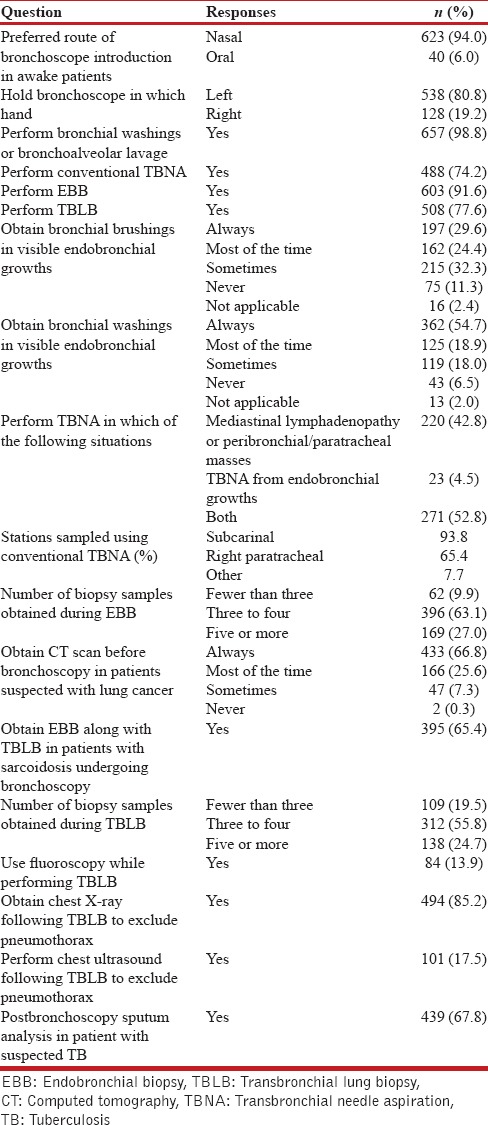

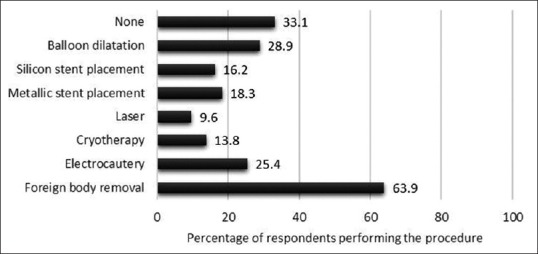

Procedural and technical aspects

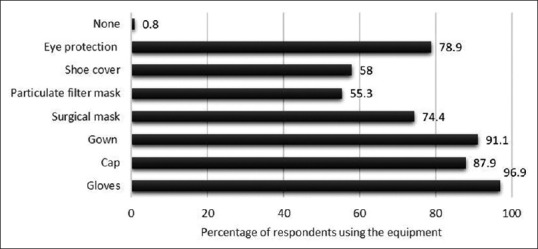

The details of responses of procedural and technical aspect section are summarized in Table 5. About 80.5% were performing Intensive Care Unit bronchoscopy and 30% of the respondents were performing therapeutic interventions including stents, electrocautery, cryotherapy, and others [Figure 1 and Table 1]. Bronchoscopic intubation for endotracheal tube placement was being performed by 62.6%. Majority (80.8%) were left-handed bronchoscopists. The nasal route was the preferred method for bronchoscope introduction by majority (94%) of the respondents. Bronchoalveolar lavage, TBNA, EBB, and TBLB were being performed by 98.8%, 74.2%, 91.6%, and 77.6%, respectively. While performing TBNA, 93.8%, 65.4%, and 7.7% were sampling the subcarinal, right paratracheal, or other stations, respectively. Only a very small number (4.5%) performed TBNA exclusively from visible endobronchial growths, while more than a half (52.8%) performed TBNA from both endobronchial growths and paratracheobronchial locations. Almost 54% would obtain bronchial brushings, while 73.6% performed bronchial washings in visible endobronchial growths, either as a routine or most of the times. Nearly 65% routinely obtained endobronchial biopsies along with TBLB in patients with sarcoidosis. Most commonly, three to four tissue pieces were obtained when performing EBB or TBLB. Only 14% were routinely using fluoroscopy while performing TBLB. Following TBLB, 85.2% routinely obtained a chest radiograph while 17.5% performed chest ultrasound to exclude pneumothorax. Almost 92.4% obtained thoracic computed tomography scan before bronchoscopy in patients with suspected lung cancer. Postbronchoscopy sputum was routinely sent for mycobacterial investigations by 67.8% in a patient with suspected tuberculosis.

Table 5.

Procedural and technical aspects of flexible bronchoscopy

Figure 1.

Details of various therapeutic bronchoscopic interventions being performed by the survey participants

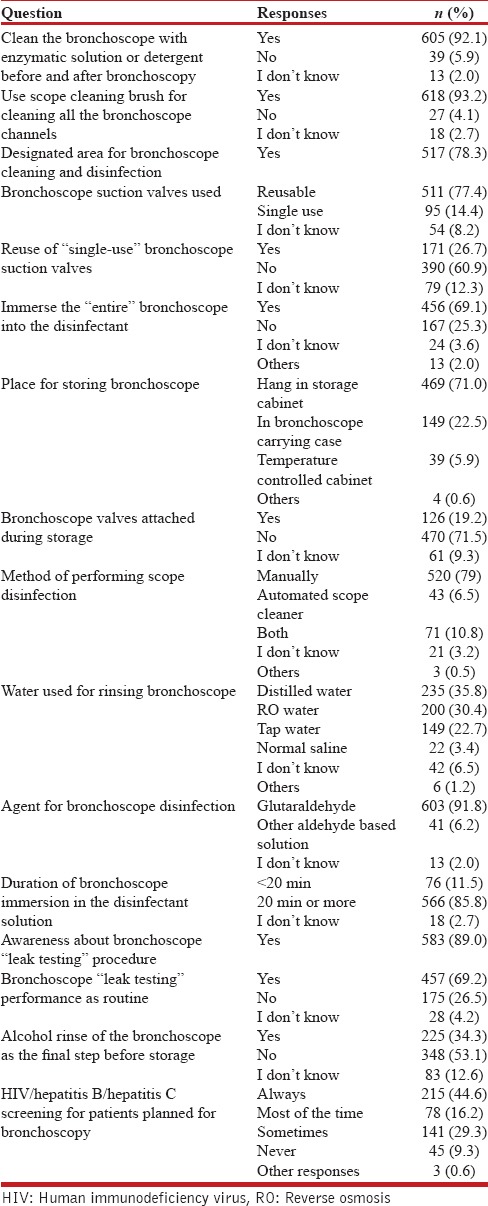

Bronchoscope disinfection and staff protection

The details of responses pertaining to this section are summarized in Table 6. For 78.3% of the respondents, there was a specifically designated area where bronchoscope disinfection was performed and 79% were performing manual scope disinfection exclusively. Almost 92% routinely cleaned the bronchoscope with enzymatic solution or any other detergent solution before and after bronchoscopy, while 93.2% regularly used a brush for cleaning the working channel of the bronchoscope. Complete bronchoscope immersion into the disinfectant solution was not being performed by 25.3%.

Table 6.

Bronchoscope disinfection and staff protection

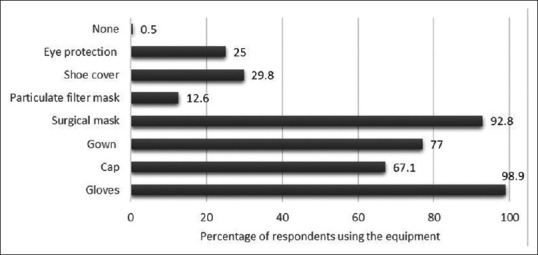

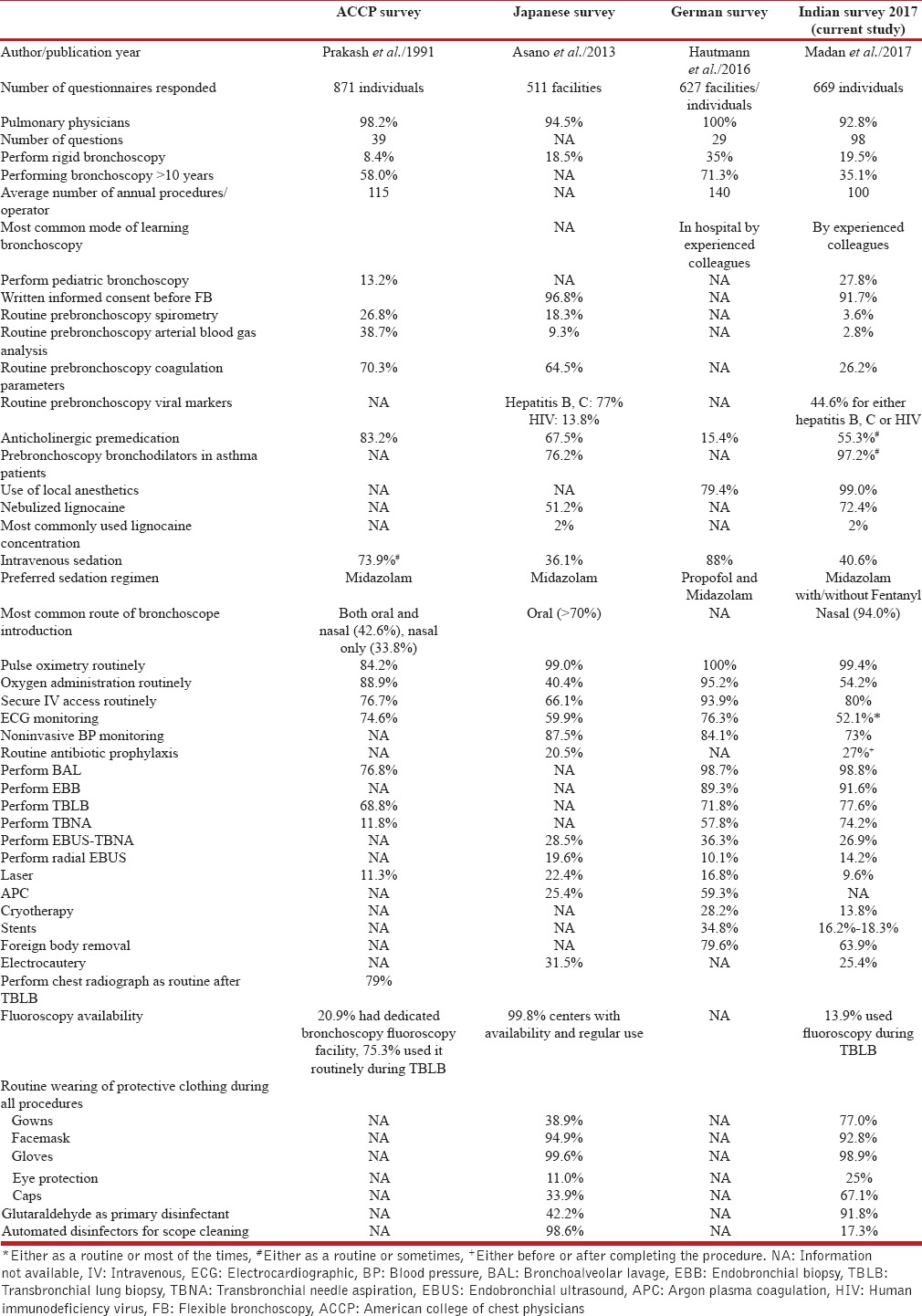

Bronchoscopes were being stored in the scope carrying case by 22.5% and 19.2% were keeping the bronchoscope valves attached during storage. Majority (92%) used 2% glutaraldehyde as the disinfectant and 85.8% were immersing the bronchoscope in the disinfectant solution for 20 min or longer. Almost 11% were unaware of the bronchoscope leak testing procedure and only 69.2% routinely performed it. 34.3% performed an alcohol rinse of the bronchoscope as the final step before storage. Patients were screened either routinely or most of the times for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C status by 60.8%. The protective equipment used by the bronchoscopists during all procedures and high-risk procedures is depicted in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

The protective equipment being used routinely by the survey respondents during all bronchoscopy procedures

Figure 3.

The protective equipment being used routinely by the survey respondents during high-risk bronchoscopy procedures

DISCUSSION

The results of the “Indian Bronchoscopy Survey” outline the bronchoscopy practices across India. The survey is large and one of the most comprehensive bronchoscopy surveys (incorporating 98 questions to assess various procedural domains) undertaken to assess the prevalent bronchoscopy practices at a national scale. The subject of bronchoscopy and interventional pulmonology has witnessed rapid developments in India over the past few years. The increasing number of publications and procedures related to bronchoscopy including therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy and EBUS-TBNA, being reported from India, has generated keen interest among pulmonologists for learning the principles and practices of bronchoscopy.[13,14,15] Interestingly, a PubMed search using the search string “bronchoscopy AND India” showed that 376 of 679 (55.4%) articles had been published after 2011.

The findings of the survey reveal several interesting facts. Nearly 50% of the respondents were based in 10 of the total 155 cities from where the responses were obtained. This suggests a concentration of tertiary health-care services in the major metropolitan cities. Nearly 70% bronchoscopists were working in multispecialty hospitals or as teaching faculty in medical colleges, indicating the requirement of sufficient resources for performing bronchoscopy. Most of the bronchoscopists had received training outside of their fellowship program. This underscores the need for developing and upgrading bronchoscopy training facilities across the country with standardized teaching curricula to promote consistency in bronchoscopy training.

The current study also highlights the variation in performance of bronchoscopy procedures as compared to the available literature. Several deviations were seen compared to current evidence.[16] For instance, 17.7% were routinely administering antibiotics following bronchoscopy despite lack of evidence to support this practice. Routine monitoring of blood pressure during the procedure was not being performed by 27%. Nearly 60% of the bronchoscopists were performing flexible bronchoscopy without conscious sedation despite the fact that sedation improves the tolerance of bronchoscopy.[17] The reasons may include the lack of adequate space in the postbronchoscopy recovery room to accommodate the large number of patients, lack of adequate trained staff, and others. However, the feasibility of performing bronchoscopy without sedation using a lower concentration of lignocaine (1%) has been well described.[18] Comparing the findings of our survey with two recently published large surveys [Table 7], bronchoscopy without sedation is also the most common practice in Japan unlike Europe and the United States where most of the bronchoscopies are performed with significant amounts of sedation.[3,4,9] As part of premedication, the use of anticholinergic drugs and nebulized lignocaine for airway anesthesia was high. The current evidence does not support the use of anticholinergic premedication and nebulized lignocaine for bronchoscopy.[17,19] The evidence against the use of nebulized lignocaine stems mostly from studies that used sedation in both the arms with and without nebulized lignocaine.[17] Thus, there is a need for more data on the utility of nebulized lignocaine in bronchoscopy performed without sedation. Nearly one-fourth of the respondents were administering transtracheal lignocaine injection, which was far larger than we anticipated.

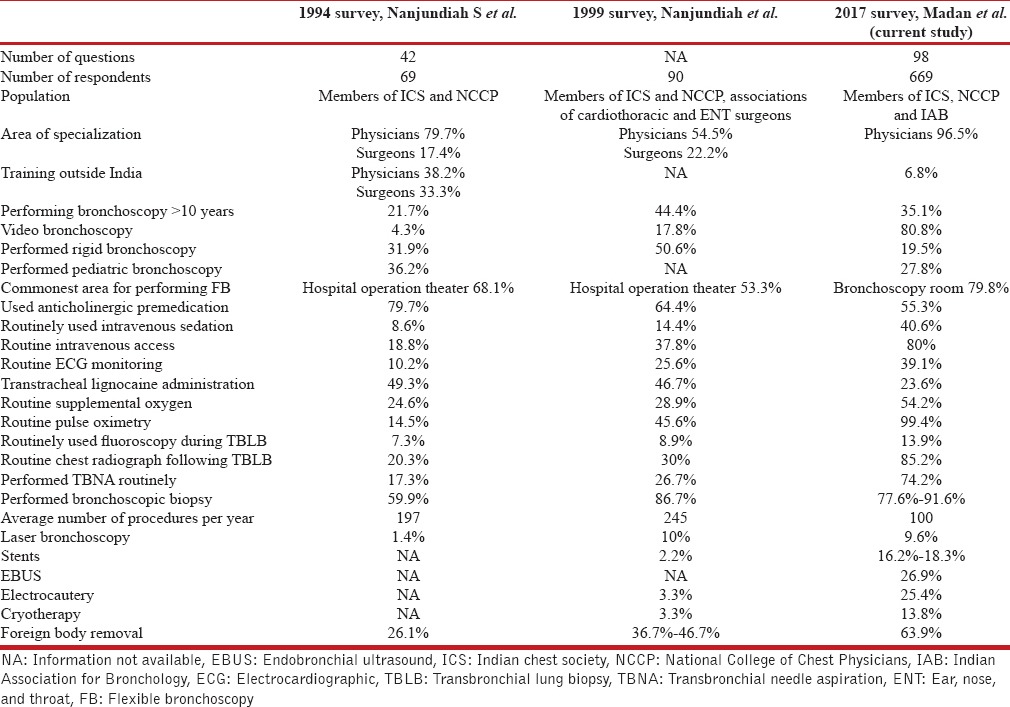

Table 7.

Comparison of the Indian Bronchoscopy Survey 2017 with other major bronchoscopy surveys

In the current study, only 29.6% were regularly obtaining bronchial brush specimens in visible endobronchial growths despite evidence that a combination of brush, biopsy, and needle aspiration provides the highest yields.[20] This might indicate either a lack of awareness or an attempt to keep the procedural cost low. Most bronchoscopists have the perception that a biopsy alone would be sufficient in visible endobronchial growths. About 35% were not obtaining endobronchial biopsies routinely along with TBLB in patients with suspected sarcoidosis. Recent studies have demonstrated that a combination of TBNA (EBUS or conventional), TBLB, and EBB provides the best diagnostic yield in patients with sarcoidosis.[21,22] Nearly three-fourth of the respondents were performing conventional TBNA which is an encouraging observation. Studies have demonstrated that conventional TBNA has a reasonable sensitivity,[23] and when combined with rapid on-site cytological evaluation can provide diagnostic yields similar to EBUS-TBNA.[24] The performance of chest radiograph following TBLB was very common (85.2%). British Thoracic Society guidelines recommend a chest radiograph following TBLB only if the patient is symptomatic or there is a clinical suspicion of pneumothorax. Only one-third of the respondents were performing therapeutic airway interventions such as thermoablative procedures and airway stents; fewer were performing EBUS-TBNA, rigid bronchoscopy, and radial EBUS. This indicates that there is an unmet need in training bronchoscopists in these advanced airway procedures.

The detailed questions regarding the disinfection protocol also provided important observations. Nearly one-fourth respondents were not practicing complete bronchoscope immersion into the disinfectant solution following bronchoscopy and a similar proportion were storing the bronchoscopes in the scope carrying case which is not a recommended practice and carries infection hazards.

We also compared the findings of our survey with the two previously published bronchoscopy surveys from India [Table 8] and other international surveys [Table 7]. The findings indicated that improvements have occurred as compared to the previous national surveys. The major improvements include the increased use of video bronchoscopy, routine securing of intravenous access, reduced anticholinergic premedication use, increased performance of TBNA, near always use of pulse oximetry, and increased performance of various therapeutic airway interventions.

Table 8.

Comparison of the three bronchoscopy surveys conducted in India till 2017

Finally, our study is not without limitations. Although we had many respondents, the use of electronic survey might have precluded certain respondents since they may not be using the electronic media and possibility of a selection bias. Areas that were not covered in the survey included the opinion regarding training and competency requirements, details of the assisting staff, complication rates, and practices of management of various bronchoscopy complications. An even detailed survey questionnaire than the current one might have reduced the response rate; therefore, we focused only the key areas.

CONCLUSION

The results of this bronchoscopy survey suggest that there is an urgent need for standardizing the training curriculum to provide uniform training to the pulmonologists and trainee physicians pursuing the field of bronchology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ikeda S, Yanai N, Ishikawa S. Flexible bronchofiberscope. Keio J Med. 1968;17:1–6. doi: 10.2302/kjm.17.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, Chaudhuri N, Gupta V, Khalid S, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults: Accredited by NICE. Thorax. 2013;68(Suppl 1):i1–i44. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, et al. Bronchoscopic practice in Japan: A survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy in 2010. Respirology. 2013;18:284–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hautmann H, Hetzel J, Eberhardt R, Stanzel F, Wagner M, Schneider A, et al. Cross-sectional survey on bronchoscopy in Germany – The current status of clinical practice. Pneumologie. 2016;70:110–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-110288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nanjundiah S. Bronchoscopy in India 2005: A survey. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2006;13:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamboni M, Monteiro AS. Bronchoscopy in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2004;30:419–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madkour A, Al Halfawy A, Sharkawy S, Zakzouk Z. Survey of adult flexible bronchoscopy practice in Cairo. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2008;15:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facciolongo N, Piro R, Menzella F, Lusuardi M, Salio M, Agli LL, et al. Training and practice in bronchoscopy a national survey in Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2013;79:128–33. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2013.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakash UB, Offord KP, Stubbs SE. Bronchoscopy in North America: The ACCP survey. Chest. 1991;100:1668–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honeybourne D, Neumann CS. An audit of bronchoscopy practice in the United Kingdom: A survey of adherence to national guidelines. Thorax. 1997;52:709–13. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.8.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth CM, Stead RJ. Survey of flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy in the United Kingdom. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:458–63. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00103702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansor AZ. Managing student's grades and attendance records using google forms and google spreadsheets. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;59:420–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madan K, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy at a tertiary care center in North India: Initial experience and systematic review of Indian literature. Lung India. 2014;31:9–15. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.125887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madan K, Mohan A, Ayub II, Jain D, Hadda V, Khilnani GC, et al. Initial experience with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) from a tuberculosis endemic population. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2014;21:208–14. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madan K, Dhooria S, Sehgal IS, Mohan A, Mehta R, Pattabhiraman V, et al. Amulticenter experience with the placement of self-expanding metallic tracheobronchial Y stents. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2016;23:29–38. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, Chaudhuri N, Gupta V, Khalid S, et al. Summary of the British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults. Thorax. 2013;68:786–7. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolz D, Chhajed PN, Leuppi J, Pflimlin E, Tamm M. Nebulized lidocaine for flexible bronchoscopy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Chest. 2005;128:1756–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur H, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Behera D, Agarwal R, et al. Arandomized trial of 1% vs 2% lignocaine by the spray-as-you-go technique for topical anesthesia during flexible bronchoscopy. Chest. 2015;148:739–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik JA, Gupta D, Agarwal AN, Jindal SK. Anticholinergic premedication for flexible bronchoscopy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of atropine and glycopyrrolate. Chest. 2009;136:347–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasgupta A, Jain P, Minai OA, Sandur S, Meli Y, Arroliga AC, et al. Utility of transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of endobronchial lesions. Chest. 1999;115:1237–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madan K, Dhungana A, Mohan A, Hadda V, Jain D, Arava S, et al. Conventional transbronchial needle aspiration versus endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration, with or without rapid on-site evaluation, for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis: A Randomized controlled trial. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2017;24:48–58. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta D, Dadhwal DS, Agarwal R, Gupta N, Bal A, Aggarwal AN, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration vs. conventional transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2014;146:547–56. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Gupta N, Bal A, Ram B, Aggarwal AN, et al. Impact of endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) training on the diagnostic yield of conventional transbronchial needle aspiration for lymph node stations 4R and 7. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madan NK, Madan K, Jain D, Walia R, Mohan A, Hadda V, et al. Utility of conventional transbronchial needle aspiration with rapid on-site evaluation (c-TBNA-ROSE) at a tertiary care center with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) facility. J Cytol. 2016;33:22–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.175493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]