mcr-1 renders colistin ineffective, which is of relevance to the management of drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. We highlight rapid increases in human gastrointestinal mcr-1 carriage prevalence (2011–2016, Guangzhou), using bacterial genomics to characterize the genetic diversity facilitating mcr-1 spread among humans/animals.

Keywords: mcr-1, genomic epidemiology, China, ESBL

Abstract

Background

mcr-1–mediated colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae is concerning, as colistin is used in treating multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. We identified trends in human fecal mcr-1-positivity rates and colonization with mcr-1–positive, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae in Guangzhou, China, and investigated the genetic contexts of mcr-1 in mcr-1–positive 3GC-R strains.

Methods

Fecal samples were collected from in-/out-patients submitting specimens to 3 hospitals (2011–2016). mcr-1 carriage trends were assessed using iterative sequential regression. A subset of mcr-1–positive isolates was sequenced (whole-genome sequencing [WGS], Illumina), and genetic contexts (flanking regions, plasmids) of mcr-1 were characterized.

Results

Of 8022 fecal samples collected, 497 (6.2%) were mcr-1 positive, and 182 (2.3%) harbored mcr-1–positive 3GC-R Enterobacteriaceae. We observed marked increases in mcr-1 (0% [April 2011] to 31% [March 2016]) and more recent (since January 2014; 0% [April 2011] to 15% [March 2016]) increases in human colonization with mcr-1–positive 3GC-R Enterobacteriaceae (P < .001). mcr-1–positive 3GC-R isolates were commonly multidrug resistant. WGS of mcr-1–positive 3GC-R isolates (70 Escherichia coli, 3 Klebsiella pneumoniae) demonstrated bacterial strain diversity; mcr-1 in association with common plasmid backbones (IncI, IncHI2/HI2A, IncX4) and sometimes in multiple plasmids; frequent mcr-1 chromosomal integration; and high mobility of the mcr-1–associated insertion sequence ISApl1. Sequence data were consistent with plasmid spread among animal/human reservoirs.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of mcr-1 in multidrug-resistant E. coli colonizing humans is a clinical threat; diverse genetic mechanisms (strains/plasmids/insertion sequences) have contributed to the dissemination of mcr-1, and will facilitate its persistence.

Colistin is one of the antibiotics of last resort for managing multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections. Colistin resistance has historically largely been due to cell wall modifications, utilization of efflux pumps, and capsule formation [1]. Transmissible, mcr-1–mediated colistin resistance was recently identified in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from hospitalized humans, animals (pigs), and raw meat (pork and chicken) in China [2], with higher rates in animal samples (~19% vs ~1% in humans).

Subsequently, mcr-1–harboring strains have been identified in humans, animals, and raw meat sampled globally [3–13]. These strains have predominantly been E. coli [14] or Salmonella species [3, 5], with up to 20% carriage prevalence in swine and poultry [6, 11], and mcr-1–positive isolates from chickens as early as the 1980s in China and 2007 in France [6, 15]. Prevalence in humans remains low [2, 4, 7, 10, 16] and mostly restricted to hospitalized patients [17, 18]. However, mcr-1 can be carried in the healthy human gut [18, 19].

The association of mcr-1 with other broad-spectrum resistance mechanisms, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and/or carbapenemases [20–25], could represent a major clinical problem. The identification of mcr-1 in multiple plasmid types, including IncI2 [2, 25], IncHI2 [22], IncX4 [12, 25], IncP [26], and IncF [23] plasmids, is consistent with multiple mcr-1 mobilization events, potentially facilitating the association of mcr-1 with other resistance mechanisms, thereby creating multidrug-resistant bacterial hosts.

In this study, we investigated human fecal carriage of mcr-1 and of mcr-1 in third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae in Guangzhou, China, over 5 years. Given that colistin resistance is of particular clinical relevance in the context of multidrug resistance, we used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to characterize a subset of 3GC-R isolates to identify relevant genetic structures, using 3GC resistance as a marker for wider multidrug resistance.

METHODS

All inpatients and outpatients submitting any clinical specimens during the study timeframe to the hospital microbiology laboratories for diagnostic purposes were asked to participate in the study by means of an invitation included with the diagnostic test report returned to the patient. Samples came from 3 hospitals in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, serving a population of approximately 15 million over an area of approximately 10000 km2. Recruitment and sample collection occurred continuously (except January 2012, February 2013, and February 2014; holiday months; staff shortages); samples were not de-duplicated by patients. Ethical approval was given by Sun Yat-Sen University; individual consent for the use of fecal samples was obtained from patients.

Fecal samples were collected into sterile fecal specimen containers and plated onto Columbia blood agar within 2 hours of collection. A cotton swab was used to inoculate the agar with specimen (plate incubated for 18–24 hours at 37°C). Subsequently, up to 10 colonies of Enterobacteriaceae were subcultured to MacConkey agar plus cefotaxime (2 mg/L), and species identification was confirmed by 16S rDNA sequencing (Supplementary Methods). All cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates were stored (lysogeny broth plus 30% glycerol, –80°C). Sweeps of cultured growth from the original Columbia blood agar plates were also similarly stored.

All frozen sweeps of cultured growth from feces (n = 8022) and individual cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates (n = 20332) were subsequently recultured and screened for mcr-1 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Supplementary Methods). Cefotaxime-resistant isolates were screened for blaCTX-M and alleles determined by sequencing (Supplementary Methods). Species identification for mcr-1–positive isolates was performed by API20E. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for all mcr-1–positive isolates by agar dilution (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing breakpoints, version 6.0; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document M100-S25) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing sampling/laboratory/sequencing workflows. Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Every cefotaxime-resistant, mcr-1–positive Enterobacteriaceae isolate of distinct species and MIC profile to May 2015 (n = 45) and a random subset from June 2015 to March 2016 (n = 44/142 [31%]) were selected for WGS. DNA was extracted using the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide/chloroform method (Supplementary Methods).

DNA extracts were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform at the Beijing Genomics Institute, using both paired-end (150-bp reads, ~350-bp insert) and mate-pair (50-bp reads, ~6-kb insert) approaches (n = 69 isolates) or paired-end reads only (n = 20 isolates; Supplementary Table 1). Libraries were prepared using standardized protocols incorporating fragmentation by ultrasonication, end repair, adaptor ligation, and PCR amplification (Supplementary Methods).

Preliminary species identification for isolates was derived from WGS using Kraken [27]; read-data were then mapped to species-specific references (28). Hybrid de novo assemblies of paired-end and mate-pair data, or paired-end data alone, were generated using SPAdes [29] version 3.6 with the “--careful” option, a set of automatically determined k-mer values (21, 33, 55, 77), and by removing contigs <500 bp or with k-mer coverage <1. In silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using BLASTn and publicly available databases (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli, http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html). Resistance genes were identified from de novo assemblies using a curated database of resistance genes [30] and BLASTn/mapping-based identification (scripts available at https://github.com/hangphan/resistType). Contigs were annotated using PROKKA [31]. Contigs containing mcr-1 were defined as “plasmid” if they contained annotations consistent with plasmid-associated loci and no obvious chromosomal loci, or “chromosomal” if >75% of annotations (excluding hypothetical proteins) were consistent with a chromosomal location.

The integrity of assemblies containing mcr-1 in chromosomal locations was assessed using REAPR [32]. We excluded any sequences with assembly sizes ≥6.5 Mb and/or mixed calls from in silico species identification/MLST.

The phylogeny was reconstructed using IQtree [33]. Branch lengths were corrected for recombination using ClonalFrameML [34] (Supplementary Methods). The phylogeny was represented in the interactive tree of life viewer (iTOL version 3, http://itol.embl.de). Insertion sequences (IS) were downloaded from ISFinder (https://www-is.biotoul.fr); sequence assemblies were queried against this database with BLASTn (requiring >95% sequence identity over >90% of the reference sequence length).

Circularization of mcr-1–harboring plasmid contigs was confirmed using Bandage [35]. For single mcr-1–harboring plasmid contigs that were not circularizable, we also used Bandage to visualize the sequencing assembly graph generated by SPAdes and manually resolved the most likely mcr-1 plasmid structures based on node (contig) linkage and contig coverage (Supplementary Methods).

Iterative sequential regression in R was used to characterize trends in fecal mcr-1 positivity (Supplementary Methods).

Sequence data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject: PRJNA354216; Supplementary Table 1).

RESULTS

Trends in Fecal mcr-1 Prevalence and Fecal mcr-1–Positive, Cefotaxime-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Prevalence

Sweeps of cultured growth from 497 of 8022 fecal samples (6.2%) were mcr-1 PCR positive, and 182 (2.3%) fecal samples harbored mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (Figure 2). The proportion of both mcr-1–positive and mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant samples increased significantly over time (P < .001). For mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant samples, this was driven specifically by increases after January 2014 (P < .001, Figure 2; 95% confidence interval [CI] for estimated date of trend change: 1 April 2013 through 1 November 2014). There was no evidence of a change in fecal sampling rates over time (negative binomial regression; incidence rate ratio, 1.02 [95% CI, .96–1.08]; P = .6).

Figure 2.

Monthly proportions of mcr-1–positive human fecal samples in Guangzhou, China, 2011–2016. A, Fecal samples harboring mcr-1–positive isolates. B, Fecal samples harboring mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant isolates. Black line represents estimated prevalence by iterative sequential regression (ISR), with gaps representing months with missing data. Blue lines at the base of the graph represent 95% confidence intervals around the breakpoints estimated by the ISR model. C, Raw counts for each category and sampling denominator (total number of fecal samples), by calendar year (or partial year as specified).

From fecal samples harboring mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, 187 distinct isolates from 182 fecal samples from 179 individuals were identified (E. coli, n = 173; K. pneumoniae, n = 13; Enterobacter cloacae, n = 1). Of these, 23 isolates from 22 individuals had ertapenem MICs of ≥0.5 mg/L (earliest isolate in 2013). One hundred forty-four of 179 (80%) individuals were hospital inpatients at sampling (median stay, 14 days [range, 3–258 days; interquartile range, 7–21 days]).

Whole-Genome Sequence of mcr-1, Cefotaxime-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Species- and Strain-Level Diversity

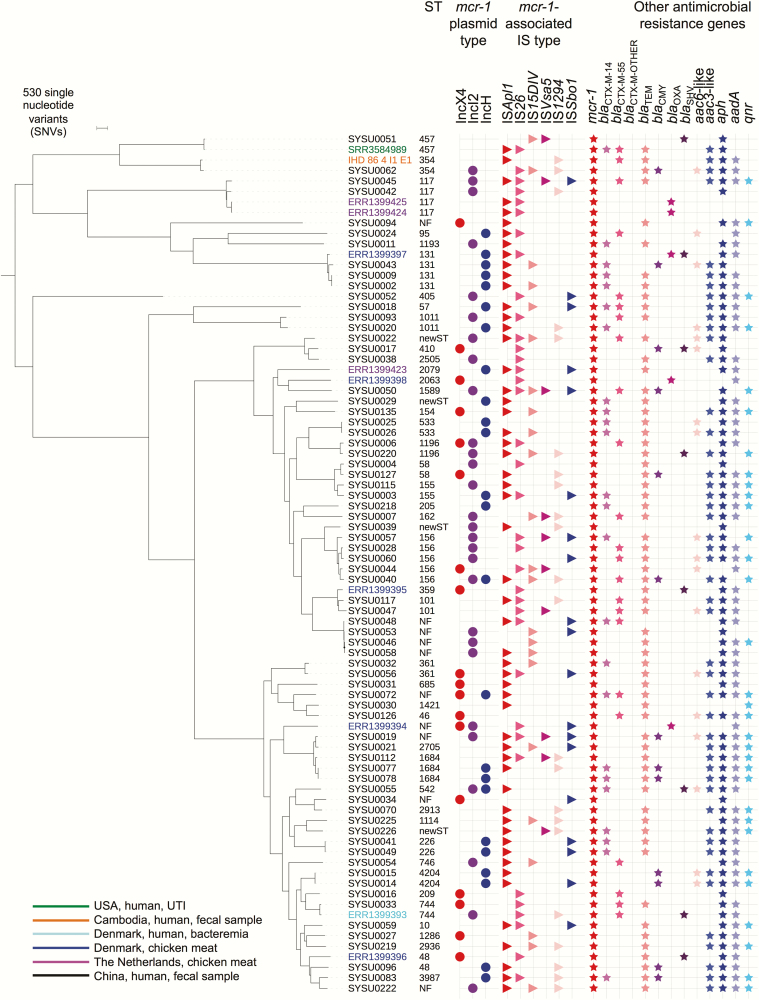

Of 89 of 187 isolates selected for WGS (see Methods), 11 of 45 consecutive isolates pre–May 2015 and 5 of 44 randomly selected isolates post–June 2015 failed quality control (Supplementary Table 1), leaving 73 sequences for analysis (70 E. coli, 3 K. pneumoniae). For E. coli, these represented 48 sequence types (STs) (Figure 3), ST156 being the most common (n = 5), with most isolates (n = 33) representing singleton STs. Other global disease-causing lineages were also identified, including ST131, ST155, and ST405 [36], and for K. pneumoniae, ST15 and ST307. Three pairs of isolates from different patients were separated by zero single nucleotide variants (SNVs) (SYSU0077/SYSU0078; SYSU0002/SYSU0009 and SYSU0014/SYSU0015), representing likely direct/indirect transmissions. All others were >1126 SNVs apart.

Figure 3.

Phylogeny of sequenced Escherichia coli study isolates, plus available reference sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (n = 11), and associated sequence types; plasmid incompatibility groups; insertion sequences within 5 kb of mcr-1 on either the same contig or contigs associated through the assembly graph; and antimicrobial resistance genes present within the isolates (presence represented by respective colored shapes). Abbreviations: IS, insertion sequence; NF, not found; ST, sequence type; UTI, urinary tract infection.

mcr-1 and IS Diversity

A novel mcr-1 allele was identified (G3A; loss of the first methionine [n = 2; SYSU0052, SYSU0010]); these isolates remained colistin-resistant. Another isolate had mcr-1 disrupted by an IS1294 element, previously described downstream of mcr-1 (n = 1; SYSU0039) [8].

IS may contribute to plasmid–plasmid and plasmid–chromosome rearrangements and gene mobilization. We found 99 different IS types in the 73 sequenced isolates, with a median of 15 (range, 7–29) IS types per isolate.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles and Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in mcr-1–Positive, Cefotaxime-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Rates of cross-class resistance in mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant isolates were high (Table 1); only carbapenems, nitrofurantoin, and tigecycline demonstrated susceptibility rates ≥80% (similar rates in subset of sequenced isolates; Table 1). Among the sequenced isolates, 58 of 73 (79%) harbored blaCTX-M, including (i) group 9–like alleles: 14 (n = 22), 27 (n = 4), 65 (n = 7), 110 (n = 1), 130 (n = 1); (ii) group 1–like alleles: 1-like (n = 1), 3 (n = 1), 11 (n = 1), 55/55-like (n = 21), 136 (n = 1); and (iii) hybrid alleles: 64 (n = 3), 123 (n = 2). Thirteen (18%) sequenced isolates had 2 blaCTX-M variants, and in 3 (carrying blaCTX-M-14,27/55,55/123), blaCTX-M was located on the same contig as mcr-1. For 11 (15%) isolates, no cefotaxime resistance mechanism could be identified (Supplementary Table 1). Multiple other resistance genes were identified; 3 isolates harbored blaCMY and 1 blaDHA (Supplementary Table 1). In carbapenem-nonsusceptible isolates that were sequenced (6/23), no genes encoding carbapenemases were identified; carbapenem nonsusceptibility in these isolates was attributed to the presence of ESBLs (blaCTX-M, blaOXA-10) plus porin gene mutations.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of mcr-1–Positive Enterobacteriaceae Isolates Obtained Following Selective Screening Culture of Feces on Agar Supplemented With Cefotaxime (2 mg/L)

| No. (%) of Isolates Resistant | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Amoxicillin- clavulanate | Cefotaxime | Ceftazidime | Cefepime | Colistin | Gentamicin | Amikacin | Ertapenem | Imipenem | Meropenem | Fosfomycin | Nitrofurantoin | Ciprofloxacin | Tigecycline | |

| All isolates (n = 187) | 183 (98) | 176 (94) | 165 (88) | 131 (70) | 139 (74) | 179 (96) | 130 (70) | 47 (25) | 23 (12) | 4 (2) | 16 (9) | 101 (54) | 19 (10) | 152 (81) | 24 (13) |

| Sequenced isolates (n = 73) | 73 (100) | 59 (81) | 67a (92) | 60 (82) | 57 (78) | 71 (97) | 54 (74) | 20 (27) | 6 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 43 (59) | 5 (7) | 63 (86) | 9 (12) |

Six isolates had minimum inhibitory concentrations of ≤1 (susceptible) when tested following selective screening culture. Of these, 1 harbored blaCTX-M-55 and 1 blaCTX-M-65; for the other 4, no discernible third-generation cephalosporin resistance mechanism was identified following reculture and DNA extraction for whole-genome sequencing.

Genetic (Plasmid/Chromosomal) Contexts of mcr-1

The genetic context of mcr-1 was diverse. In 61 of 73 (84%) isolates, mcr-1 was located on plasmid-associated contigs (in 4 cases likely multiple plasmids), and in 4 (5%) on chromosomal contigs; in 8 (11%) the location was unclear due to assembly/annotation limitations. mcr-1 copy number per sequenced isolate was estimated at 0.27–3.54 (median, 0.97); copy number values >1 were likely due to its presence either on multicopy plasmids; as multiple copies within the same plasmid (eg, SYSU0077 [IncH]; SYSU0093 [IncI2]); or on different plasmids within the same isolate (eg, SYSU0072 [IncH and IncX4]; SYSU0220 [novel plasmid described below]).

mcr-1 on IncI Plasmids

In 27 of 61 (44%) isolates where mcr-1 was plasmid-associated, it was associated with an IncI2 replicon (directly co-located on the same contig in n = 20). Fourteen sequences represented circularizable, complete plasmid structures; this included the earliest sequenced mcr-1 plasmid, to our knowledge (SYSU0011, May 2011).

In these plasmids, the backbone and mcr-1 location were largely preserved; this was also true of the 6 noncircularizable IncI contigs harboring mcr-1 (Figure 4). In relation to mcr-1, we observed variable presence of ISApl1, but when present, it was always located upstream of mcr-1 between mcr-1 and nikB, most consistent with ancestral ISApl1-mediated acquisition of mcr-1 into an IncI plasmid backbone, and subsequent loss of ISApl1. These plasmids were also undergoing significant evolution by mutation/recombination, rearrangement, indels, and acquisition/loss of smaller mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as ISEcp1 plus blaCTX-M-55 (SYSU0060, SYSU0045) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Alignment of mcr-1 IncI2 study plasmids (complete plasmids, denoted by * if circularized using SPAdes assembly only, and by ** if circularized using SPAdes + Bandage); incompletely resolved plasmid contigs; and 3 reference plasmid sequences (sequence labels in bold). Dates of isolation are shown on the right side. Two plasmid sequences were obtained from isolates cultured from the same patient (sequence labels in blue). Pink/blue cross-links between aligned sequences demonstrate regions of sequence homology (BLASTn matches of ≥500 bp length, >95% sequence identity); dark regions within these cross-links demonstrate sequence variation. Tick marks represent 10 kb of sequence. Colored arrows demonstrate open reading frames of particular relevance; additional coding sequence annotations are shown above reference plasmid SZ02.

The mcr-1–IncI2 plasmids were also genetically highly similar to 3 previously sequenced plasmids (Figure 4): SZ02 (accession number: KU761326, blood culture, August 2015, Suzhou); the blaCTX-M-55–harboring pA31-12 (accession number: KX034083.1, chicken, August 2012, Guangzhou), and pHNSHP45 (accession number: KP347127.1, pig, July 2013, Shanghai), consistent with the dissemination of this plasmid in human cases/carriers, pigs, and chickens across China.

We also observed highly genetically related IncI plasmid backbones in 2 different E. coli host strains (ST156, 354; SYSU0060, SYSU0062) isolated from the same patient/same day, potentially consistent with within-host transfer, as well as highly genetically related plasmids within different E. coli strains and humans across periods of time consistent with direct transmission/acquisition from common sources (SYSU0019, SYSU0007).

mcr-1 on IncHI2/HI2A Plasmids

In 22 of 61 (36%) isolates where mcr-1 was plasmid associated, it co-localized with or was most plausibly on an IncHI2/HI2A plasmid. As these plasmids are large and more likely to include repeats, we were unable to fully reconstruct them. Five contigs were short (<3000 bp); the others are represented in Figure 5, alongside 2 closed reference mcr-1-IncHI2 plasmids, pSA26 (accession number: KU743384, blood culture, Saudi Arabia) and pHNSHP45-2 (accession number: KU341381, pig feces, Shanghai). These demonstrate that a homogenous backbone sequence ranging from approximately 38 kb to approximately 224 kb (of evaluable sequence) has been circulating within the study population between 2012 and early 2016, likely derived from an ancestral plasmid similar to the reference plasmids (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Alignment of mcr-1 IncHI2/HI2A plasmid contigs and 2 reference plasmid sequences (sequence labels in bold followed by dates of host strain isolation). Pink/blue cross-links between aligned sequences demonstrate regions of sequence homology (BLASTn matches of ≥500 bp length, >95% sequence identity); dark regions within these cross-links demonstrate sequence variation. Tick marks represent 10 kb of sequence. Colored arrows demonstrate open reading frames of particular relevance.

We observed apparently frequent IS/transposon-associated indel events in mcr-1–IncHI/HI2A plasmids, including of ISApl1, which was either at the 5ʹ end of mcr-1 (SYSU0003), flanking it on both sides (SYSU0014), or absent (SYSU0026). As mcr-1 was located in the same wider genetic context in 14 of 17 study plasmid contigs, this likely represents a single ISApl1–mcr-1–ISApl1 acquisition and subsequent loss of ISApl1 elements [37], similar to that seen in mcr-1–IncI plasmids in this study. Alternatively, it could represent a genetic “hotspot” facilitating multiple ISApl1–mcr-1–ISApl1 insertion events.

We also observed an mcr-1 duplication event within otherwise identical plasmid sequences in 2 isolates taken 7 days apart (SYSU0077, SYSU0078); and inversions of ISApl1–mcr-1 within the backbone (SYSU0002, SYSU0009, SYSU0055), all consistent with high rates of plasticity involving ISApl1–mcr-1 and IncHI2/HI2A structures.

mcr-1 on IncX4 Plasmids

In 15 of 61 (25%) isolates where mcr-1 was plasmid associated, it was associated with an IncX4 replicon; 6 of these represented circularizable plasmid sequences (Figure 6). IncX4–mcr-1 plasmids had a highly conserved, syntenic backbone, with limited nucleotide and indel variation over 2.5 years. They were also highly similar to 2 reference IncX4–mcr-1 plasmids, SZ04 (peritoneal fluid, Suzhou) and pAF48 (urine, Johannesburg, South Africa), consistent with national and international spread. ISApl1 was absent in all of these plasmids, but IS26-like elements were located upstream of mcr-1, suggesting the mechanism of mobilization to IncX4 is different from that in IncI and IncHI2/HI2A plasmids.

Figure 6.

Alignment of mcr-1 IncX4 study plasmids (complete plasmids, denoted by * if circularized using SPAdes assembly only, and by ** if circularized using SPAdes + Bandage); incompletely resolved plasmid contigs; and 2 reference plasmid sequences (sequence labels in bold). Dates of isolation are shown on the right side. Pink/blue cross-links between aligned sequences demonstrate regions of sequence homology (BLASTn matches of ≥500 bp length, >95% sequence identity); dark regions within these cross-links demonstrate sequence variation. Tick marks represent 10 kb of sequence. Colored arrows demonstrate open reading frames of particular relevance. Four contigs were excluded as they were small (2.0–8.75 kb).

Other Genetic Contexts of mcr-1

In 2 isolates (SYSU0048, SYSU0220), we identified new mcr-1–harboring plasmids; in 1 case, this could be completely resolved (48944 bp; Supplementary Figure 1), and was similar to pHNFP671 (accession number: KP324830.1, IncP, pig feces, isolated prior to 2014).

Chromosomal mcr-1 integration was confirmed in 4 E. coli STs (457, 1114, 1684, 2936), and plausibly in 2 others (101, 2705), consistent with at least 4 independent chromosomal integration events in diverse strains (5% sequenced E. coli isolates), suggesting capacity for non-lineage-specific vertical dissemination of mcr-1.

DISCUSSION

Widespread transmissible colistin resistance is of major concern in the context of multidrug resistance, as colistin is commonly used to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, despite its drawbacks [38, 39]. In this, the largest study of human fecal carriage and WGS of mcr-1 isolates to our knowledge, we observed alarming sequential increases in carriage of mcr-1, and of mcr-1–positive, cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae fecal carriage (predominantly E. coli) over 5 years. We also found significant diversity and genetic plasticity of MGEs harboring mcr-1 that may explain some of these dramatic increases.

IncI plasmids are narrow host-range plasmids [40], commonly isolated from E. coli and Salmonella species, and implicated in the spread of the ESBL gene blaCTX-M among Enterobacteriaceae, particularly in China [41, 42]. CTX-M-55 has been found in E. coli in animals in China, and CTX-M-55/55-like variants were seen with mcr-1 in IncI2 plasmids in 2 different E. coli strains (ST156, ST117) in this study. Previously, it has been postulated that an IncI2 plasmid backbone acquired a 3080-bp ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 complex from an IncA/C plasmid, with a mutation resulting in conversion to blaCTX-M-55 within this structure [43]. The same signature sequence was observed in our isolates, as well as another recently sequenced IncI2 plasmid harboring blaCTX-M-55 from a chicken E. coli isolate in Guangzhou (August 2012) [44], consistent with the spread of this plasmid across humans and animals. blaCTX-M-64 was also observed on an IncI mcr-1 plasmid in this study (SYSU0115, ST155); this allele is thought to have arisen from recombination between blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-15 on IncI plasmids in food animals in China [43].

IncHI2/HI2A plasmids are typically large (>250 kb) [45], multidrug-resistant plasmids that have been associated with a range of antibiotic and metal resistance genes in Salmonella species and E. coli isolated from humans and food-producing animals [46]. Similar to the IncI plasmids, our genetic analyses suggest an initial mcr-1 acquisition event, and subsequent loss of ISApl1 units and rearrangements of the plasmid backbone.

In at least 4 sequenced isolates, mcr-1 had been integrated into the chromosome, a phenomenon observed in at least 2 other studies (E. coli ST156, Beijing [47]; E. coli ST410, Germany [48]). Our data suggest 2 additional mcr-1 chromosomal integrations: 1 in association with an integrative element promoting IS activity, and 1 in association with an ISEc23/IS30-like/IS1294 element, which has played a role in the mobilization of blaCMY-2 in Salmonella species and E. coli [49]. The multifarious means by which chromosomal integration of mcr-1 appears to occur is of concern, as this may facilitate more stable inheritance of this gene.

The variable extent of genetic diversity observed within the plasmid families here (IncHI2/HI2A and IncI > IncX4) may reflect different evolutionary rates for these plasmid families or may be consistent with earlier acquisition of ISApl1-mcr-1 composite transposons by IncHI2/HI2A and IncI2, most likely within poultry and pig farms in which regular colistin exposure represents a major selection pressure [2]. The acquisition of mcr-1 by IncX4 plasmids appears to be unrelated to the presence of ISApl1, and possibly involves IS26/26-like structures.

This study has several limitations. First, although we observed significant increases in fecal carriage of mcr-1–harboring isolates, we did not assess possible risk factors associated with increasing incidence. We did not de-duplicate samples by patient for the whole dataset; however, analysis of participant study identifiers for the mcr-1/3GC-resistant isolates suggests that replicate sample submission was minimal (~2%), and would not have explained the incidence trends observed. We only investigated the culturable component of feces for overall mcr-1 prevalence, as DNA was extracted from sweeps of cultured feces, and we may therefore have underestimated true mcr-1 colonization by not performing PCR direct on DNA extracts from whole feces. Our WGS strategy only targeted culturable, cefotaxime- and colistin-resistant isolates from feces, as we were predominantly interested in investigating the genomic epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. The diversity of strains and MGEs harboring mcr-1 may therefore be even greater. We did not screen for non-mcr-1 variants, which have also been shown to confer colistin resistance, nor did we screen potential animal or nonhuman reservoirs. Finally, due to resource limitations we were unable to sequence all mcr-1–positive isolates, or to resequence those that failed. We were also unable to undertake any long-read sequencing, increasingly the method of choice in assembling plasmids.

Despite these limitations, we have demonstrated that human fecal carriage of mcr-1–positive E. coli has increased dramatically in Guangzhou over the last 2 years, reaching similar proportions (20%–30%) to animals (pigs, chickens) over the preceding 3–4 years in the same region of China [2]. Our genetic analyses suggest the rapid emergence of several major plasmid vectors of mcr-1 within numerous multidrug-resistant E. coli strains carried by humans, and highlight the significant degree of plasticity in these plasmid vectors harboring mcr-1 over short periods of time.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We acknowledge the work of the Modernizing Medical Microbiology sequencing pipeline team (Nicholas Sanderson) and informatics team (Ian Szwajca, Trien Do, Dona Foster), collectively represented as the Modernizing Medical Microbiology Informatics Group.

Disclaimer. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or PHE.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81722030 and 81471988); the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong (grant number 2016A020219002); the 111 Project (grant numbers B13037 and B12003); and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number 16ykzd09). Additional funding support was provided through a University of Oxford/Public Health England (PHE) Clinical Lectureship to N. S. and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. D. W. C. is an NIHR senior investigator.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain JM. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front Microbiol 2014; 5:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quesada A, Ugarte-Ruiz M, Iglesias MR et al. Detection of plasmid mediated colistin resistance (MCR-1) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica isolated from poultry and swine in Spain. Res Vet Sci 2016; 105:134–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prim N, Rivera A, Rodriguez-Navarro J et al. Detection of mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in polyclonal Escherichia coli isolates in Barcelona, Spain, 2012 to 2015. Euro Surveill 2016; 21. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.13.30183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Webb HE, Granier SA, Marault M et al. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:144–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perrin-Guyomard A, Bruneau M, Houee P et al. Prevalence of mcr-1 in commensal Escherichia coli from French livestock, 2007 to 2014. Euro Surveill 2016; 21 doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.6.30135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kluytmans-van den Bergh MF, Huizinga P, Bonten MJ et al. Presence of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in retail chicken meat but not in humans in the Netherlands since 2009. Euro Surveill 2016; 21:30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stoesser N, Mathers AJ, Moore CE, Day NP, Crook DW. Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 and pHNSHP45 plasmid in human isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:285–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olaitan AO, Chabou S, Okdah L, Morand S, Rolain JM. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuo SC, Huang WC, Wang HY, Shiau YR, Cheng MF, Lauderdale TL. Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in Escherichia coli isolates from humans and retail meats, Taiwan. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71:2327–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen NT, Nguyen HM, Nguyen CV et al. Use of colistin and other critical antimicrobials on pig and chicken farms in southern Vietnam and its association with resistance in commensal Escherichia coli bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016; 82:3727–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mulvey MR, Mataseje LF, Robertson J et al. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:289–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grami R, Mansour W, Mehri W et al. Impact of food animal trade on the spread of mcr-1-mediated colistin resistance, Tunisia, July 2015. Euro Surveill 2016; 21:30144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Falgenhauer L, Waezsada SE, Yao Y et al. RESET Consortium Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacteria in Germany. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:282–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen Z, Wang Y, Shen Y, Shen J, Wu C. Early emergence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quan J, Li X, Chen Y et al. Prevalence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae recovered from bloodstream infections in China: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang R, Huang Y, Chan EW, Zhou H, Chen S. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:291–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Tian GB, Zhang R et al. Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arcilla MS, van Hattem JM, Matamoros S et al. COMBAT Consortium Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:147–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Skov RL, Monnet DL. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (mcr-1 gene): three months later, the story unfolds. Euro Surveill 2016; 21:30155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haenni M, Poirel L, Kieffer N et al. Co-occurrence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase and MCR-1-encoding genes on plasmids. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:281–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhi C, Lv L, Yu LF, Doi Y, Liu JH. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:292–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zeng KJ, Doi Y, Patil S, Huang X, Tian GB. Emergence of the plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene in colistin-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:3862–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Du H, Chen L, Tang YW, Kreiswirth BN. Emergence of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:287–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li A, Yang Y, Miao M et al. Complete sequences of mcr-1-harboring plasmids from extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:4351–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malhotra-Kumar S, Xavier BB, Das AJ, Lammens C, Butaye P, Goossens H. Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 harboured on a multidrug resistant plasmid. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:283–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 2014; 15:R46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Pankhurst L et al. Modernizing Medical Microbiology Informatics Group (MMMIG). Evolutionary history of the global emergence of the Escherichia coli epidemic clone ST131. mBio 2016; 7:e02162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012; 19:455–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stoesser N, Batty EM, Eyre DW et al. Predicting antimicrobial susceptibilities for Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates using whole genomic sequence data. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68:2234–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt M, Kikuchi T, Sanders M, Newbold C, Berriman M, Otto TD. REAPR: a universal tool for genome assembly evaluation. Genome Biol 2013; 14:R47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 2015; 32:268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Didelot X, Wilson DJ. ClonalFrameML: efficient inference of recombination in whole bacterial genomes. PLoS Comput Biol 2015; 11:e1004041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2015; 31:3350–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. Multiresistant gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011; 35:736–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Snesrud E, He S, Chandler M et al. A model for transposition of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 by ISApl1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:6973–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Landersdorfer CB, Nation RL. Colistin: how should it be dosed for the critically ill?Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36:126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Humphries RM. Susceptibility testing of the polymyxins: where are we now?Pharmacotherapy 2015; 35:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carattoli A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:2227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong MH, Liu L, Yan M, Chan EW, Chen S. Dissemination of IncI2 plasmids that harbor the blaCTX-M element among clinical Salmonella isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:5026–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lv L, Partridge SR, He L et al. Genetic characterization of IncI2 plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-55 spreading in both pets and food animals in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:2824–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu L, He D, Lv L et al. bla CTX-M-1/9/1 hybrid genes may have been generated from blaCTX-M-15 on an IncI2 plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:4464–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun J, Li XP, Yang RS et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of IncI2 plasmid co-harboring blaCTX-M-55 and mcr-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:5014–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. García-Fernández A, Carattoli A. Plasmid double locus sequence typing for IncHI2 plasmids, a subtyping scheme for the characterization of IncHI2 plasmids carrying extended-spectrum β-lactamase and quinolone resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:1155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fang L, Li X, Li L et al. Co-spread of metal and antibiotic resistance within ST3-IncHI2 plasmids from E. coli isolates of food-producing animals. Sci Rep 2016; 6:25312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu H, Qu F, Shan B et al. Detection of mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) from different hospitals in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:5033–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Falgenhauer L, Waezsada SE, Gwozdzinski K et al. Chromosomal locations of mcr-1 and blaCTX-M-15 in fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli ST410. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22:1689–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tagg KA, Iredell JR, Partridge SR. Complete sequencing of IncI1 sequence type 2 plasmid pJIE512b indicates mobilization of blaCMY-2 from an IncA/C plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4949–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.