INTRODUCTION

The prevention and management of epidemic infections are a major responsibility of national leaders in peace and war. Belfast suffered outbreaks caused by meningococci in 1906,1907, 19081,2 and 19153; Bordeaux, France, endured Spanish influenza in 19184,5. In the UK, cerebrospinal fever became notifiable in 19126, so that epidemiologic data were collected for the World War I years7,8,9. Canadian troops brought meningococci to the UK in 1914-15; it spread to the civilian population7,8. Two to four percent of persons carry meningococcus in their pharynx but during an epidemic, the percentage of carriers may increase ten to twenty-fold. Four main groups can be identified by agglutination tests. A, formerly caused the majority of epidemics, while B was responsible for sporadic infections, until historically replaced by Group C as the predominant epidemic organism7. Group D rarely caused human disease7,8,9,10.* The use of Flexner’s serum during the Belfast outbreaks of 1906-1908 reduced mortality from 82 percent to 25-35 percent2. In the British military, mortality in 1915 approached 50% even with the use of serum10. In 1915, Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, Sir William Osler reported on recent outbreaks of cerebrospinal fever in military and naval camps and barracks, and the existence of a “meningitic type of poliomyelitis”8.

John C. Slessor (JCS) had lived with William Osler’s family in Oxford for 5 years just before World War I11. (Fig 1) In 1915, Professor Sir William Whitla1,2 and Regius Professor Sir William Osler wrote authoritative reviews of the management of meningococcal epidemics8.

Fig 1.

Twelfth Night, Oxford Preparatory School, 1909. JCS, in the front row (circled), was two years younger than the other actors. From the Archives of the Dragon School, Oxford, and reproduced with their permission. JCS lived in the nearby Osler house from which Harvey Cushing was married in 1911. Revere circled (top). Lady Osler left JCS in her will “a massive oak chest that belonged to her great-grandfather”, Paul Revere of Boston, famous revolutionary, silversmith and coroner of Boston 1796-180112.

The following year, 1916, the Oslers’ only child Revere died of war wounds received as a gunner subaltern in the Ypres Salient. Harvey Cushing, a close family friend who had been married from the Osler’s home, attempted to save his life and broke the sad news to the senior Oslers11,13.

EDUCATION OF A PRESIDENT

After attending the Groton School in Massachusetts, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) wanted to attend the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis14. Roosevelt had been given for Christmas 1897, aged 15, A.T. Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power upon History. His distant cousin and close family friend President Theodore Roosevelt, and FDR’s father, James, both advised “Harvard” as preferable. James died during FDR’s freshman year at Harvard.

The following summer, FDR took his mother, Sara, to see Kaiser Wilhelm II. FDR sailed his mother in the Roosevelt yacht to Sorge, Norway, adjacent to the S.M.Y. Hohenzollern. Sara and her son FDR invited the Kaiser to tea. He accepted and reciprocated on the Hohenzollern14.

On June 7, 1910 Theodore Roosevelt gave the Romanes Lecture at Oxford sponsored by Professor Osler15. In 1913, FDR was appointed Assistant Secretary, United States Navy14,16. He served 8 years with wide-ranging responsibilities which eventually affected Northern Ireland. FDR was in control of building the U.S. Navy’s extensive installations along the Gironde, Bordeaux. FDR provided the impetus for the 1918 mine blockage from Scotland to Norway and the promotion of an effective U.S. Naval Air Service campaign against German U-boats14,16. FDR took two trips to WWI front lines in France and Italy. Wherever he went, he was treated like a Head of State. On his inspection tours, FDR’s personal U.S. Navy Flag was the first U.S. flag raised and flown over the Royal Navy flags since the War of 1812.

Returning from Europe after his 1918 World War I trip, FDR was seriously ill with ‘Spanish’ flu and subsequent pneumonia. Upon arrival in Hoboken, NJ, he was transported by ambulance to his mother’s home in Manhattan where he was nursed by his wife Eleanor, together with U.S. Navy nurses14. Post-Armistice, on his January 2, 1919 return trip to Europe, he was accompanied by his wife Eleanor, by authority of the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels14.

The U.S. Navy in 1919 employed the largest airplanes in the world, the NC flying boats. NC4 was the first plane to be flown across the Atlantic, two weeks before Alcock and Brown, landing at Lisbon, Portugal on May 27, 1919 from Washington, D.C. via the Azores14.

CATALINAS AND FDR

FDR became President and Commander-in-Chief of the United States on March 4, 193317 (Fig. 2). FDR let it be known that as Commander-in-Chief he would allocate U.S. heavy bombers. Within 6 months, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany17. In October 1933, the U.S. Navy contracted Consolidated, Martin and Douglas to build competing prototypes for a patrol flying boat18,19. Each Consolidated Catalina, winner of the competition, cost $US 90,000. Four thousand fifty-one were produced, of which approximately 200 were based in Northern Ireland during World War II18,19,20.

Fig 2.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 44th Governor of New York State, 1929-1932. Oil on Canvas by Jacob H. Perskie (1865-1941) 122 cm x 97 cm, ca. 1932. From the collections of the State of New York, Hall of Governors, Albany, NY and reproduced with their permission.

FLYING FORTRESS AND FDR

On August 8, 1934, Boeing filed its proposal for the B-17 Heavy bomber18,19,20. Eleven months later a Boeing-financed Flying Fortress prototype flew from Boeing Field18. The U.S. Air Corps placed, with FDR’s approval an order for 65 B-17 Flying Fortresses18. On the prototype’s second flight it crashed and killed its pilots18,19. FDR told the RAF Tactical Planning Committee, which included JCS (see below) and Dowding (later victor of the Battle of Britain), that 12,000 B-17s would be built in the event of war with Germany. Otherwise the RAF and French could tender for them21. By July 1945, 12,731 had indeed been produced by Boeing18,19,20.

JCS

Sir John (Jack) Cotesworth Slessor GCB 1948, KCB 1943, DSO 1937, MC 1916, later Head of RAF (JCS) was born in India on 3 June 1897, the son of Major Arthur Kerr Slessor of the Sherwood Foresters22 . JCS married Hermione Guinness in 192322. JCS was on the Air Staff, Air Ministry 1928-30, Instructor Staff College, Camberley 1931-1934; back to India 1935-37. He was in command of No. 3 Wing Quetta, 1935, Director of Plans, Air Ministry 1937-41, ADC to King George VI, 1938, Air Representative to French Conversations 1938-3921,22,23. In 1940, he went to the USA, as sole RAF representative to the Anglo-American staff conversations and in US 1942, leaving Jan. 1943, then en route to the Casablanca Conference with FDR and Prime Minister Churchill23,24. JCS wrote much of the Final Report. Slessor flew from the UK to Washington DC seven times from 1940 through the end of 1943 and spent many weeks there23,24 (Fig. 3).

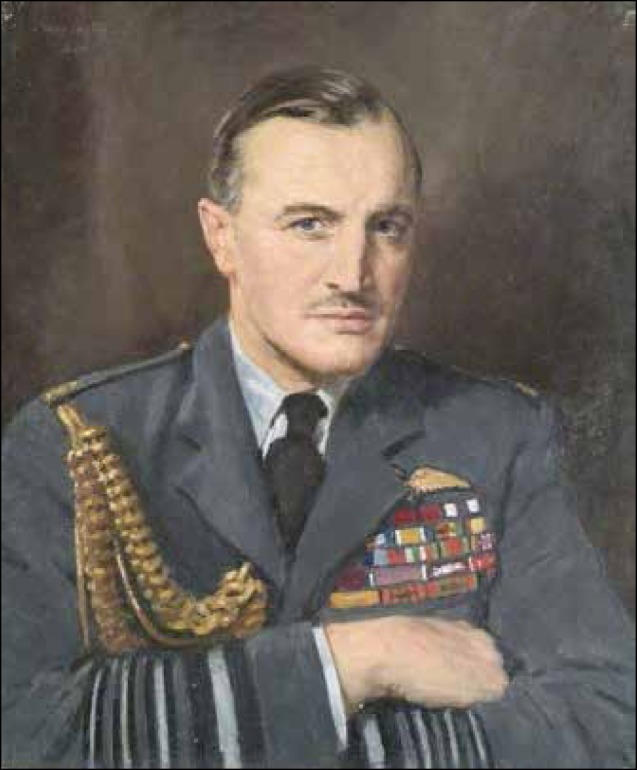

Fig 3.

John C. Slessor, by Mary Eastman, 1947. Oil on canvas, 60.3 cm x 50.8 cm. From the collections of the Imperial War Museum, London, IWM Image no. ART LD 6512.

JCS knew that FDR had been severely criticised for tardiness in deploying anti-sera to the large U.S. Navy base at Bordeaux, France4,9. JCS, despite his post-polio leg weakness, had become a war hero in the RFC and RAF. As a protégé of Lord Trenchard, JCS was given important planning posts for development of planes for the inter-war RAF25. In 1935 JCS was in command of the RAF group of squadrons at Quetta when the earthquake struck: thirty thousand died26. JCS and Donegal-born Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Law Montgomery arranged for the burial of the dead and the supply of vaccines, drugs, equipment, nurses, physicians and engineers26.

In late 1940, JCS was sent as the sole RAF representative to prepare and take part in the American-British-Canadian (ABC) conference in Washington, D.C.23,24. There, Slessor met FDR at the White House and they worked out the U.S. proposed planning for Northern Ireland24,27,28. FDR insisted on Creevagh Hospital (Londonderry) being built for “My Navy”. FDR recommended sending 30,000 U.S. workers from a still neutral U.S.A. to help local artisans build Creevagh Hospital, docks and airfields for “My Navy” and “My Army”, since “My Bombers” needed a convalescent lodge and hospital therein. FDR likened Lough Foyle to the Gironde where he had supervised U.S. construction in 1917-1919. FDR knew of JCS’s RAF plan M. He shared with JCS his own enquiries, projections and modus operandi23,24.

JCS, with FDR’s assistance, found 674 Hudsons, 91 Catalinas, 58 Liberators and 20 Flying Fortresses awaiting delivery to the UK29,30,31. JCS wrote to the head of the RAF; “The present system is whereby we bribe a few American pilots:….we want….at least 1,000 pilots.29” FDR intervened and arranged that the Fortresses be flown by RAF pilots from Seattle or Vancouver to Prestwick or Aldergrove. The other pilots were to be U.S., Canadian and British air-men. On arrival at Belfast hotels, the ten-gallon hats, high-heeled Texan boots and Canadian hooded parkas were certainly noticed. Sir Frederick Banting, of insulin fame, was the first civilian fatal casualty from a Hudson being ferried across the North Atlantic. He froze to death after surviving a Newfoundland crash31,32.

As part of the ABC 1 and 2 plans of 1940 and early 1941, 26 airfields were planned for Northern Ireland. Langford Lodge was planned to be an American assembly, modification and repair depot27. Langford Lodge had a satellite airfield at Greencastle, County Down. Between 1942 and 1945, 48 aircraft accidents were directly related to Langford Lodge Air Depot27; the Medical, Dental and Nursing staff were U.S. citizens and Lockheed employees. The Station Surgeon was Major Samuel Blank27. In planning this hospital, both JCS and FDR knew of the 1907, 1908 and 1915 Belfast Cerebrospinal fever epidemics and the U.S. forces Bordeaux 1917-18 epidemics of cerebrospinal fever and influenza1,2,3,7,8,9. FDR also knew of JCS’s Oslerian background and his 1935 Quetta earthquake experience: fly in or stock vaccines and drugs11,26,33.

FDR and JCS strongly influenced Allied deployment in both Northern Ireland and elsewhere. Both were good at dealing with the US leadership of Ernest King, Commander of the US Navy and H.H. “Hap” Arnold, Commander of the US Army Air Force34. The US provided the majority of planes for RAF Coastal Command and the escort carriers of the Allies34. Why did JCS and FDR get on so well? Both had paralytic polio—JCS walked with one or two sticks and for cricket was allowed a runner; FDR employed leg braces and human aid. Each admired the other’s charm and intellect. Slessor’s wife, Hermione, was a Guinness and FDR’s wife, Eleanor, was Theodore Roosevelt’s favourite niece14.

HUDSONS AND LOCKHEED

Early on 13 May 1938, leaving a crowd of journalists and aviation enthusiasts at Burbank, near Los Angeles, California, Waclaw Makowski flew a LOT purchased Lockheed Hudson L14 to Warsaw, Poland. The arrival in Warsaw was triumphant. A radio failure was due to faulty cable insulation short-circuiting at higher altitude 35. Makowski later led RAF Squadron 300 to sink German invasion barges in the Battle of Britain. Conversion of 300 Squadron from Fairey Battles to Vickers Wellingtons commenced in October 1940. On March 23, 1941, Makowski led his squadron to bomb Berlin. Remarkably, no Wellington was lost. In 1984, Makowski was honoured by the U.S. Airforce together with Jimmy Doolittle (leader of the 1942 Tokyo raid), Chuck Yeager (breaking of the sound barrier) and Adolf Galland (Air Battle for Europe, Luftwaffe ace). At the USAF presentation of Great Moments in Aviation History, Makowski said “I am honoured to be… among aces…whose achievements surpass mine35”.

By February 1939, Hudsons began to be delivered to RAF squadrons. At the outbreak of war, 78 were in RAF service36,37,38. During World War II the 2,000 Hudsons of RAF Coastal Command flew out of all 26 Northern Irish Airfields36. Two thousand nine hundred and forty-one Hudsons were produced by Lockheed between 1938 and 194319,20,23,37.

LIBERATOR B-24 JCS AND FDR

In May 1938, the French government issued a “specification to U.S. firm, Consolidated, for a heavy bomber”39. FDR approved this initiative. A contract for a prototype was signed on 30 March 193939. On 29 December 1939 the Liberator B-24 made its maiden flight from the Lindbergh Field at the Consolidated plant in San Diego39.

After the June 1940 French capitulation, 2 Liberators flew into Nutts Corner to form the genesis of RAF Coastal Command Liberators based in Northern Ireland. Approximately 300 of the 18,482 Liberators built saw service from Northern Ireland28,36,39.

COMMANDER IN CHIEF

In 1940, FDR asked for an estimate of “overall production requirements… to defeat our potential enemies”30. As far as the Air Corps was concerned, 4 officers were named to “make a forecast of our needs”. The veterans Harold George and Ken Walker were named to this panel along with Larry Kuter and H.S. Hansell, Jr., from the younger echelon of the U.S. Army Air Force. This was their estimate:

2,200,000 men

63,467 airplanes

239 combat groups; along with 108 separate squadrons not formed in groups.†”

“Our full-strength air offensive against Germany could not be developed before April 1944. The prophecy of that panel of four officers seems outstanding,” wrote LeMay post World War II30. FDR kept this reply to himself and Hopkins30.

The existing Slessor arrangement with FDR, had resulted from the ABC conversations of January to March 194121,24. Although never formally approved (but initialed by FDR), the Slessor Agreement was essentially followed for six months after 29 March 194121,40. The Slessor agreement with FDR “called for Britain to retain all the output from her own production, all U.S. produced aircraft from the British orders already in process.” The Slessor Agreement included the now surrendered French orders and an allocation from the continuing American production as well as the “entire output” from any new U.S. expansion24. If the U.S. were to be drawn into World War II any new U.S. capacity would be allocated between the U.S. and the RAF on a 50-50 basis21,24. Between 1941 and 1945 18,482 Liberators were completed39. After Pearl Harbor the Slessor Agreement basically continued but FDR increased U.S. production of Liberators “to one every hour”39.

MEDICAL COVERAGE

Typically, the RAF had 11 Medical Officers in Northern Ireland at any one time during World War II41. The practice of these MOs depended on the plane type being flown. For 502 Ulster Squadron (Limavady) many survivors had burns, fractures and head injuries from Whitley take off, landings and mountain crashes42,43. In 1941, one-half of the Limavady Whitleys were lost with the majority of their aircrew; many were drowned in the Atlantic and their bodies not recovered44,45. When 502 was moved to attack the ‘U-boat choke point, the Bay of Biscay’, medical coverage had to be expanded41,46. The RAF hospitals and EMS hospitals provided surgery for both RAF Coastal Command and for Ernest King’s US Liberators47,48. Unfortunately, US Navy Liberator navigation was inadequate, U.S. crews having been trained in the Gulf of Mexico46. King insisted that they be retrained by RAF Coastal Command. King then transferred them to Morocco46. With long range Liberators, some Africa-based, the Battle of the Bay of Biscay was won47,48. The US and Royal Navies also interdicted, with 502 Ulster Squadron’s help, German blockade runners from Japan. During the Battle of the Bay the Germans learned presumably from captured aircrew, the sites of RAF hospitals at Torquay, near Truro and in Glamorgan. These were bombed by the Luftwaffe and nurses and RAF aircrew killed41,49.

NORTH ATLANTIC TRANSFER

Approximately 10,000 U.S. manufactured aircraft were flown across the North Atlantic in World War II31. The Hudsons flew primarily to Aldergrove and the B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators to Prestwick29,31. Four percent were lost to the North Atlantic or crashed in Northern Ireland or Scotland30,31. The Catalinas flew to Lough Neagh, Lough Erne, Castle Archdale or Greenock on the Clyde31.

Medical cover for the aircrew was provided by 11 RAF physicians and 50 Princess Royal RAF nurses at Castle Archdale, as well as the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in Northern Ireland47,49. By March 1943, Ballykelly had been opened and No. 120 Squadron had operational very long-range Liberators and Squadron 220, at Nutt’s Corner, had U.S.–transferred Flying Fortresses in time for the successful victory in the Battle of the Atlantic late in 194347,48.

TRAINING AND CARE

My‡ father-in-law, George Waller joined RAF Coastal Command 502 Squadron (Ulster) in 194050,51. In 1941, Waller became Staff officer for Air Vice Marshal Sir Geoffrey R. Bromet, D.S.O., AOC 19 Group in Plymouth; appointed in charge of training and safety, Waller deposited Bromet in the leaves and branches of a big oak50,.51. The Tiger Cub’s broken propeller, converted to hold a clock, remains in the family. Bromet, in his role as Commander-in-Chief went on to conquer and occupy the Azores and in January 1943, Waller was transferred to the staff of JCS, newly AOC Coastal Command50 (Fig.4). During 1944 and 1945, Waller remained at Coastal Command headquarters with Sir Sholto Douglas, MC, DFC, who succeeded JCS as AOC CC, 1944-4552 (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Then Princess Elizabeth and her mother the Queen visited JCS in 1943 when he was Commander of RAF Coastal command. As Equerry to King George VI, JCS had helped organize the Royal visit of Their Majesties in June 1939 to FDR and his family at Hyde Park, New York.

Fig 5.

William Sholto Douglas, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, oil on canvas, 1940, by Sir Herbert James Gunn, RA (1893-1964), 72.2 cm x 63.5 cm. From the collections of the Imperial War Museum, Art.IWM ART LD 997, and reproduced with their permission exclusively for this Medical History.

JCS when summoned to meet alone in FDR’s private White House office remembers FDR’s extensive detailed knowledge and charm. “He appeared to know almost all details of performance and modifications to “My Heavy Bombers”24, whether deployed in the RAF or ‘My Navy’s Air Force’ or Hap Arnold’s.” India, Montgomery, the Guinnesses and the Oslers were also discussed with FDR during JCS’s meetings in FDR’s study.

Sholto Douglas wrote of being summoned in Cairo, Egypt to a one-on-one meeting with FDR. The guards were dismissed, and FDR gave an accurate and detailed “history of the Douglas clan and their relationships with FDR’s Scottish grandmother”53. FDR “very nearly had me eating out of his hand” but when Allied Aegean policy was discussed, FDR left no doubt that he was in charge.

My father-in-law, now Wing Commander Waller, recalled a conversation with A/C/M Sir Sholto Douglas when playing bridge with him. “I made some remark slightly uncomplimentary about Air Marshal Dowding who had been Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. Saying nice things about people was not one of Sholto’s strong points, but when he heard my remark he said, ‘Young man, never say anything like that again.’ We all owe our lives to Dowding. Had it not been for his work in the years before the War we would have lost in 1940. I was only posted to succeed him as Commander-in-Chief Fighter Command at the end of 1940 because he was absolutely exhausted.”

In late 1942, FDR’s wife Eleanor flew to Langford Lodge, Northern Ireland to see the results of the planning and deployment of U.S. Forces47. Creevagh Hospital, U.S. Navy Overseas Hospital Number 1, had not had a fatality although busy with casualties from the war47,54. Nutrition and health of U.S. forces and their morale were most satisfactory28. Sholto Douglas states “I had been impressed by the forcefulness and alertness of her [Eleanor’s] mind. She and her husband shared a great strength of character”53. After World War II, Sholto Douglas served as Military Governor of the British Zone in Germany, succeeding Field Marshall B.L. Montgomery. In 1948 he was created Lord Douglas of Kirtleside. In later years he was Scholar and later Hon. Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford University52.

FDR received a state funeral and is buried on the grounds of his Hyde Park, New York home overlooking the Hudson River. On JCS’s death, his son, Group Captain J.A.G. Slessor received a letter from Lt. General Ira C. Eaker of the USAF which states, “It was a rare experience of a lifetime to have known and cooperated with Sir John Slessor. I shall never forget his friendship and never cease to admire his great qualities of mind and heart”21,55. JCS voiced, in 1943, similar feelings about FDR to my father-in-law.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Miss Gay Sturt, Archivist, Dragon School (formerly Oxford Preparatory School), Oxford, UK for expert assistance with archival records and permission to reproduce the photograph of the cast of the 1909 production of Twelfth Night. The authors thank Mr. Liam O’Reilly and Ms. Alyson Stanford of the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) for expert assistance with war-time hospital records. The authors thank Ms. Robyn Ryan, Deputy Director of Operations for Special Projects, Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, State Capitol, Albany, NY, for permission to reproduce the portrait of FDR, 44th Governor of New York State, 1929-1932. The authors thank the Copyright and Permissions Staff of the Imperial War Museum, London for permission to reproduce the portrait of Air Marshal Sholto Douglas. The 1943 photograph of the Queen and Princess Elizabeth with Sir John C. Slessor is reproduced with its owners’ permission.

Footnotes

Provenance: internally peer reviewed.

The Medical Research Council Report (9) and other contemporaneous sources use the Gordon Classification of Types I, II, III and IV.

Here is what the U.S. Army Air Force and the U.S. Navy actually ended up with, as of 1945: 2,400,000 men, 80,000 aircraft, 243 combat groups30

This and any other first-person references refer to the first author.

UMJ is an open access publication of the Ulster Medical Society (http://www.ums.ac.uk).

REFERENCES

- 1.Milligan E. Cerebrospinal fever. The Practitioner. 1915;94:831-60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robb G. Special discussion on the epidemiology of cerebrospinal meningitis. Epidemiological section. Proc R Soc Med. 1915; 8:55-60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitla W. The treatment of cerebrospinal meningitis (spotted fever). The Practitioner May 1915;94:631-5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oxford JS. The so-called Great Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 may have originated in France in 1916. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2001;356(1416):1857-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honigsbaum M. A History of the Great Influenza Pandemics: death, panic and hysteria 1830-1920. London: I.B. Tauris; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Underwood EA. Recent knowledge of the incidence and control of cerebrospinal fever. Brit Med J. 1940;1(4140):757-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian HA, editor. Cerebrospinal fever. In: Christian HA, editor. Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 13th ed. New York: D. Appleton-Century Co.; 1938. p. 81-9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osler WJ. Remarks on cerebro-spinal fever in camps and barracks. Brit Med J. 1915; 1(2822):189-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon MH, Bell AS, Tulloch WJ, Glover JA. Medical Research Council. Privy Council. Cerebrospinal fever. studies in the bacteriology, preventive control, and specific treatment of cerebrospinal fever among the military forces 1915-19. Special Report Series No. 50. London: HM Stationery Office; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughn VC, McKay RJ, editors. Infections due to Neisseria meningitides (N. intracellularis). In: Vaughn VC, McKay RJ, editors. Nelson’s Textbook of pediatrics. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1975. p. 578-80. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slessor J. These Remain. A Personal Anthology. Memories of Flying, Fighting and Field Sports. London: Michael Joseph; 1969. p.23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jentzen JM. Death investigation in America: Coroners, Medical Examiners and the pursuit of medical certainty. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. p.15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brothers in Arms: ‘Obviously All Was Lost’– The life and death of Edward Revere Osler. London: The Western Front Association; Available from: http://westfrontassoc.mtcdevserver.com/great-war-people/brothers-arms/2245-obviously-all-was-lost-the-life-and-death-of-edward-revere-osler.html#sthash.IYoe7VUA.dpbs. Last accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Kay JT. Roosevelt’s Navy: the education of a Warrior President, 1882-1920. New York: Pegasus Books; 2013. p. 18, 22, 27, 31, 233, 238-9, 258-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cushing H. The Life of Sir William Osler. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1925. p. 219-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trask DF. FDR at War, 1913-1921. In: Marolda EJ, editor. FDR and the US Navy. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. p. 13-18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buhite RD, Levy DW, editors. FDR’s Fireside Chats. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1992. p. 11, 141-2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien PP. How the War was won: air-sea power and Allied victory in World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p.103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craven WF, Cate JL, editors. The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume I. Plans and Early Operations January 1939-August 1942. Chicago, IL: Office of Air Force History and University of Chicago Press; 1948. p. 65-71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tate JP. The Army and its Air Corps. Army policy toward aviation 1919-1941. Chapter 6. Preparation for War. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press, June 1998. p.157-84. Available from: http://www.au.af.mil/au/aupress/digital/pdf/book/b_0062_tate_army_air_corps.pdf Last accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly CJ. Marshall of the Royal Air Force, Sir John Cotesworth Slessor and the Anglo-American Air-Power Alliance, 1940-1945. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A & M University, 19 February 2002. No. 20020305 171. Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA399435. Last accessed November 2017.

- 22.Sir John (Jack) Cotesworth Slessor GCB 1948, KCB 1943, DSO 1937 MC 1916. Who’s Who. Adam & Charles Black: London; 1966. p. 2826. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slessor J. Chapter XII. Special Duty in the United States. In: Slessor JC. The Central Blue: the autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p. 314-38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slessor J. Chapter XIII. The A.B.C. Staff conversations. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p.339-65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slessor J. Chapter III. Plans: 1928 to 1930—Trenchard and air control. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p.45-75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slessor J. Chapter V. Disaster at Quetta. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p.101-18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay WA. Wartime Langford Lodge: A documented account of aircraft accidents at the former American assembly, modification and repair depot, in Northern Ireland 1943-45. Crumlin, Northern Ireland: William Alan Lindsay; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedley-Whyte J, Milamed DR. The Battle of the Atlantic and American preparations for World War II in Northern Ireland, 1940-1941 (before Pearl Harbor). Ulster Med J 2015;84(2):113-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slessor J. Chapter XIV. 1941-1942: Bomber Group Commander. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p.366-96. [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeMay CE, Kantor M. Book III GHQ Air Force. Book IV AAF: War against Germany. Mission with LeMay. My Story. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday; 1965. p.127-93, 197-318. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christie CA. Ocean Bridge: The history of RAF Ferry Command. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1995. p.66-72. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millward B. Historical item: The death of Banting and its connection with Kidderminster. Kidderminster, UK: Kidderminster Civic Society; 2016. Available from: http://kidderminstercivicsociety.btck.co.uk/HistoricalItemTheDeathofBanting. Last accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton N. Chapter 9: Quetta. In: Monty. The making of a General.1887-1942. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1981. p. 244-59. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold HH. Global Mission. London: Hutchinson & Co.; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makowski W. Chapter XXX. Flight to Poland. In: Makowski W. A Civilian in Uniform. Memoirs from my life and wars 1897-1986. Located at: Professor Hedley-Whyte (Private Collection). Marbella, Spain (Private Printing ISBN 978-83-65005-62-5); 1978. p. 391-407. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrie AW. The Cinderella Service: Coastal Command 1939-1945. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kightly J. Database: Lockheed Hudson. Aeroplane. 2015;43(10):73-88. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Royal Airforce Museum Lockheed Hudson IIIA. London: Royal Airforce Museum; Available from: http:/www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/collections/lockheed-hudson-iiia/ Last accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowman M. Chapter 1. America’s Liberator: Development history. In: Bowman, M. B-24 Liberator. Combat legend. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing; 2003. p.5-16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.United States – British Staff Conversations Report, 27 March 1941. Washington, DC: US Serial. Available from: http://www.ibiblio.org/ pha/pha/pt_14/x15-049.html. Last accessed November 2017.

- 41.Rexford-Welch SC, ed. The Royal Air Force Medical Services. 3 vols. London: HMSO, 1954-58. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedley-Whyte J, Milamed DR. Orthopaedic surgery in World War II: Military and medical role of Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 2016;85(3):196-202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedley-Whyte J, Milamed DR. Severe burns in World War II. Ulster Med J. 2017;86(2):114-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinn J. Wings over the Foyle. A history of Limavady Airfield in World War II. Belfast: World War II Irish Wreckology Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quinn J, Reilly A. Covering the Approaches. The war against the U-boats. Belfast: World War II Irish Wreckology Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slessor J. Chapter XVII. Coastal Command. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p. 464-507. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedley-Whyte J, Milamed DR. Battle of the Atlantic: Military and medical role of Northern Ireland (after Pearl Harbor). Ulster Med J. 2015;84(3):182-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slessor J. Chapter XVIII. The Battle of the Atlantic. In: The Central Blue: The Autobiography of Sir John Slessor, Marshal of the RAF. New York: Frederick A. Praeger; 1957. p. 508-38. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mackie M. Wards in the Sky: The RAF’s Remarkable Nursing Service. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waller G. Five years in Coastal command. In: Fopp M, editor. High Flyers. 30 Reminiscences to Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the Royal Air Force. London: Greenhill Books in Association with the Royal Air Force Museum; 1993. p. 217-23. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waller GS. World War II Memoir. (unpublished manuscript).

- 52.William Sholto Douglas, 1st Baron Douglas of Kirtleside, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, GCB, MC,DFC (23 Dec. 1893-29 Oct 1969). Who’s Who. Adam & Charles Black: London; 1966. p.861. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sholto Douglas W, Wright R. Years of Command. The second volume of the autobiography of Sholto Douglas, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Lord Douglas of Kirtleside, G.C.B., M.C., D.F.C. London: Collins; 1966. p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carroll FM. United States Armed Forces in Northern Ireland during World War II. New Hibernia Rev 2008; 12(2):15-36. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eaker IC. Letter Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker to Group Captain J.A.G. Slessor, 23 July 1979. Air Force Historical Research Center (AFHRC), MICFILM 23290, Frame 266. In: Connolly, CJ. Marshall of the Royal Air Force, Sir John Coteworth Slessor and the Anglo-American Air-Power Alliance, 1940-1945. [Doctoral Dissertation]. [Houston: ]: Texas A & M University; 19 February 2002. 316p. p.1 Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA399435. Last accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]