Abstract

Most of the studies on chiropteran endoparasites in Argentina come from the Central and Northeast regions of the country, and there is only one parasitological study of bats from the Argentinean Patagonia. The aim of this study is to describe the helminth fauna of 42 Myotis chiloensis, comparing the composition and the structure of the endoparasite communities between two populations, inhabiting different environments in Andean humid forest and the ecotone between forest and Patagonian steppe. A total of 697 helminths were recovered from 33 bats: five species of trematodes, Ochoterenatrema sp., Paralecithodendrium sp., Parabascus limatulus, Parabascus sp., and Postorchigenes cf. joannae, two species of cestodes, Vampirolepis sp. 1 and Vampirolepis sp. 2, and three species of nematodes, Allintoshius baudi, Physaloptera sp., and Physocephalus sp. All the helminths, but Physocephalus sp., were recovered from the small and large intestine. This is the first survey of M. chiloensis’ helminth fauna. All the species, but A. baudi, represent new records of helminths in Patagonian bats. There were differences of parasite species richness between localities and both bat populations share almost half of the endoparasite species. Different preferences for intestinal regions were found for three species of trematodes in the bats from the site in the humid forest. Myotis chiloensis serves as both a definitive and intermediate host for endoparasites in the Patagonian ecosystem.

Keywords: Bats, Parasites, South America

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This is the first survey of the helminth communities of the bat Myotis chiloensis.

-

•

Five species of trematodes, two of cestodes, and three of nematodes were reported.

-

•

Preferences for intestinal regions were found for three species of trematodes.

-

•

Most of the bats were infested with trematodes and nematodes, simultaneously.

1. Introduction

Studies on chiropteran endoparasites are limited around the world, which means that the diversity of bat's parasites is probably underestimated (Lord et al., 2012, Portes Santos and Gibson, 2015). Most of the studies in Argentina come from the Central and Northeast regions of the country, where 17 species of nematodes, 12 of trematodes, and four of cestodes have been reported (Boero and Delpietro, 1970, Lunaschi, 2002a, Lunaschi, 2002b, Lunaschi, 2004, Lunaschi, 2006, Lunaschi et al., 2003, Drago et al., 2007, Lunaschi and Drago, 2007, Ramallo et al., 2007, Lunaschi and Notarnicola, 2010, Oviedo et al., 2009, Oviedo et al., 2010, Oviedo et al., 2012, Oviedo et al., 2016, Fugassa, 2015, Portes Santos and Gibson, 2015, Milano, 2016) (Table 1). There is only one parasitological study of bats from Argentinean Patagonia, describing the trichostrongylid nematode, Allintoshius baudi, from Myotis aelleni collected in El Hoyo de Epuyén, Chubut province (Vaucher and Durette-Desset, 1980).

Table 1.

Previous and new records of endoparasites species infesting Argentinian bats. When available, the number of hosts investigated was detailed (N), indicated with a letter the corresponding study.

| Helminth species | Host | Province | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trematoda | |||

| Anenterotrema liliputanium | Molossops temminckii (N = 2a), Molossus rufus (N = 20b) | Misiones, Corrientes | aLunaschi and Notarnicola, 2010; bMilano, 2016. |

| Anenterotrema eduardocaballeroi | Molossops temminckii (N = 5b), Molossus rufus (N = 20b) | Corrientes | bMilano, 2016. |

| Gymnoacetabulum talaveraense | Eumops pagatonicus (N = 66b), Molossus molossus, Myotis albescens (N = 35b), Myotis levis, Tadarida brasiliensis, | Buenos Aires | Lunaschi, 2002a, Lunaschi, 2002b, Drago et al., 2007, Lunaschi and Drago, 2007; aLunaschi and Notarnicola, 2010; bMilano, 2016. |

| Limatulum umbilicatum | Sturnira lilium | Buenos Aires | Lunaschi et al., 2003, Drago et al., 2007. |

| Limatulum oklahomense | Molossus rufus (N = 20b), Myotis cf nigricans (N = 31b), Myotis albescens (N = 35b) | Buenos Aires | bMilano, 2016. |

| Ochoterenatrema labda | Eumops patagonicus (N = 66b), Molossops temminckii (N = 5b), Molossus rufus (N = 20b), Myotis albescens (N = 35b), Myotis cf nigricans (N = 31b), Myotis levis, Tadarida brasiliensis, | Buenos Aires, Corrientes | Drago et al., 2007; aLunaschi and Notarnicola, 2010; bMilano, 2016. |

| Ochoterenatrema sp. | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Parabascus limatulus | Tadarida brasiliensis (N = 1c), Myotis chiloensis | Buenos Aires, Río Negro | cLunaschi, 2004; This study. |

| Parabascus sp. | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Paralecithodendrium conturbatum | Tadarida brasiliensis | Buenos Aires | Lunaschi and Drago, 2007. |

| Paralecithodendrium aranhai | Eumops patagonicus (N = 66b), Myotis cf nigricans (N = 31b) | Buenos Aires | bMilano, 2016. |

| Paralecithodendrium sp. | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Postorchigenes cf. joannae | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Topsiturvitrema verticalia | Myotis levis (N = 15d) | Buenos Aires | dLunaschi, 2006, Lunaschi and Drago, 2007. |

| Urotrema scabridum | Eumops bonaerensis, Eumops patagonicus (N = 66b), Molossops temminckii (N = 5b), Molossus molossus (N = 6b), Molossus rufus (N = 20b), Myotis albescens (N = 35b), Myotis levis, Myotis cf nigricans, (N = 31b) Phyllostomus sp., Tadarida brasiliensis | Buenos Aires, Misiones, Corrientes | Drago et al., 2007; aLunaschi and Notarnicola, 2010; bMilano, 2016. |

| Cestoda | |||

| Vampirolepis decipiens | Eumops abrasus | Misiones | Boero and Delpietro, 1970. |

| Vampirolepis elongata | Pygoderma bilabiatum | Misiones | Boero and Delpietro, 1970. |

| Vampirolepis guarany | Artibeus lituratus (N = 10b), Eptesicus patagonicus (N = 66b), Molossus rufus (N = 20b) | Corrientes, Misiones | bMilano, 2016. |

| Vampirolepis cf macroti | Eptesicus furinalis (N = 16b) | Corrientes | bMilano, 2016. |

| Vampirolepis sp. 1 | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Vampirolepis sp. 2 | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study. |

| Nematoda | |||

| Allintoshius baudi | Myotis aelleni, Myotis chiloensis | Chubut, Río Negro | Vaucher and Durette-Desset, 1980; This study. |

| Allintoshius parallintoshius | Myotis albescens (N = 1e) | Entre Ríos | eOviedo et al., 2009. |

| Allintoshius sp. | Eptesicus furinalis (N = 7e) | Entre Ríos | eOviedo et al., 2009. |

| Aochotheca sp. | Chiroptera gen. sp., Eptesicus furinalis (N = 7e), Myotis levis (N = 14e) | Entre Ríos | Ramallo et al., 2007; eOviedo et al., 2009. |

| Anoplostrongylus sp. | Eptesicus furinalis (N = 16b), Eumops bonaerensis (N = 3e), Eumops patagonicus (N = 5e; N = 66b), Eumops perotis (N = 1b), Molossus rufus (N = 20b) | Corrientes, Buenos Aires, Entre Ríos | eOviedo et al., 2009; bMilano, 2016. |

| Biacantha normaliae | Desmodus rotundus | Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán | Oviedo et al., 2012. |

| Capillaria sp. | Molossus rufus (N = 20b), Molossops temminckii (N = 5b), Sturnira lilium (N = 9b), Tadarida brasiliensis | Buenos Aires, Corrientes | Drago et al., 2007; bMilano, 2016. |

| Cheiropteronema striatum | Artibeus planirostris (N = 64f) | Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán | fOviedo et al., 2010. |

| Litomosoides sp. | Sturnira lilium | Misiones | Boero and Delpietro, 1970. |

| Litomosoides molossi | Molossus molossus | Entre Ríos | Oviedo et al., 2016. |

| Litomosoides chandleri | Artibeus planirostris, Eumops perotis, Sturnira erythromos, Sturnira lilium, Sturnira oporaphilum | Entre Ríos | Oviedo et al., 2016. |

| Litomosoides saltensis | Eptesicus furinalis | Entre Ríos | Oviedo et al., 2016. |

| Molostrongylus acanthocolpos | Myotis temminckii (N = 14) | Entre Ríos | Oviedo et al., 2009. |

| Pterygodermatites sp. | Eumops patagonicus (N = 66b) | bMilano, 2016. | |

| Physaloptera sp. | Chiroptera gen. sp., Eptesicus furinalis (N = 7e), Myotis chiloensis | Entre Ríos, Río Negro | Ramallo et al., 2007; eOviedo et al., 2009; This study. |

| Physocephalus sp. | Myotis chiloensis | Río Negro | This study |

| Rictularia sp. | Molossops temminckii (N = 9e) | Entre Ríos | eOviedo et al., 2009. |

Myotis chiloensis, known as “Murcielaguito de Chile (Chilean Little bat)” is an endemic vespertilionid bat from the Argentinean and Chilean Patagonia. These bats have been collected in the Argentinean provinces of Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut, and Tierra del Fuego (Barquez and Díaz, 2009, Barquez et al., 2013, Díaz et al., 2011). They are small, insectivorous bats which feed mainly on insects of the orders Lepidoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera, and Trichoptera (Giménez and Giannini, 2013, Ossa and Rodríguez San Pedro, 2015).

The aim of this study is to report for the first time the helminth fauna of M. chiloensis and to compare the composition and the structure of the endoparasite communities between two populations, inhabiting different environments in Andean Patagonia.

2. Materials and methods

A total of 42 specimens of M. chiloensis were captured in two rural localities in the Southwest region in the Patagonian province of Río Negro. The survey was part of the project “Estudio de fauna de pequeños vertebrados (anfibios, reptiles and mamíferos) en el Oeste de la provincia de Río Negro”, directed by Dr. Richard Sage, and it did not require any additional approval by an animal ethics committee. The first sample (N = 16) was captured in the site “Manso” (41°35′45″ S, 71°45′58″ W), located in the humid forest, on December 2011. The second sample (N = 26), was captured in the site “Luis Ruiz” (41°54′40″ S, 71°25′23″ W), located in the ecotone between the forest and the steppe, on January 2014 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Location of the sampling sites in the province of Río Negro, Argentina.

2.1. Host and parasitological procedures

The bats were sacrificed by an overdose of sodic pentobarbital injectable and preserved and fixed in a 10% formaldehyde neutral solution. The bats' abdominal and thoracic cavities and organs were examined with a stereoscopic microscope. The intestine was divided in three sections: 1) duodenum, 2) small intestine (jejunum and ileum), and 3) large intestine and rectum. The site of infection and the number of parasites found were registered and the specimens which were found detached from the host during the necropsy were not assigned to any particular intestinal section. Permanent and transitory slides were made in order to identify the helminths. The trematodes were dehydrated gradually in ethylic alcohol (70%, 96%), stained with Grenacher's carmin, and mounted in Canada balsam. The cestodes and nematodes were cleared with Aman's lactophenol. All parasites were photographed and measured using a Zeiss Primo Star compound microscope equipped with a digital camera (Zeiss Axiocam ERc 5s). One specimen of each species was deposited in the Colección Nacional de Parasitología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia, Buenos Aires, Argentina (MACN-Pa).

2.2. Statistical procedures

The prevalence (P) and mean intensity (MI) was calculated for each species of endoparasite in order to characterize quantitatively the infections (Bush et al., 1997; Villarreal et al., 2006). The infracommunities species richness was quantified and a Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing them between the two localities. In order to estimate the undetected species, the species richness was estimated using Chao and Jackknife (ChaoLocality ± SE, JackLocality ± SE) (these analyses were performed in R 3.4.2 using the vegan package). The Jaccard Index was used for comparing the similarity of presence/absence of species between the two localities (Krebs, 1989) and the Simpson's Diversity Index (DLocality) and the Pielou's Evenness Index (J'Locality) were used for evaluating the diversity and dominance of species in the two localities (Bush et al., 1997, Villarreal et al., 2006). The Fager's Affinity Index was used for establishing the association rate between two species (Fager, 1957). In order to determine the preference for an intestinal region, a Kruskall-Wallis test was used, comparing the abundance of species among the sites of infection (Conover, 1980).

3. Results

3.1. Species composition

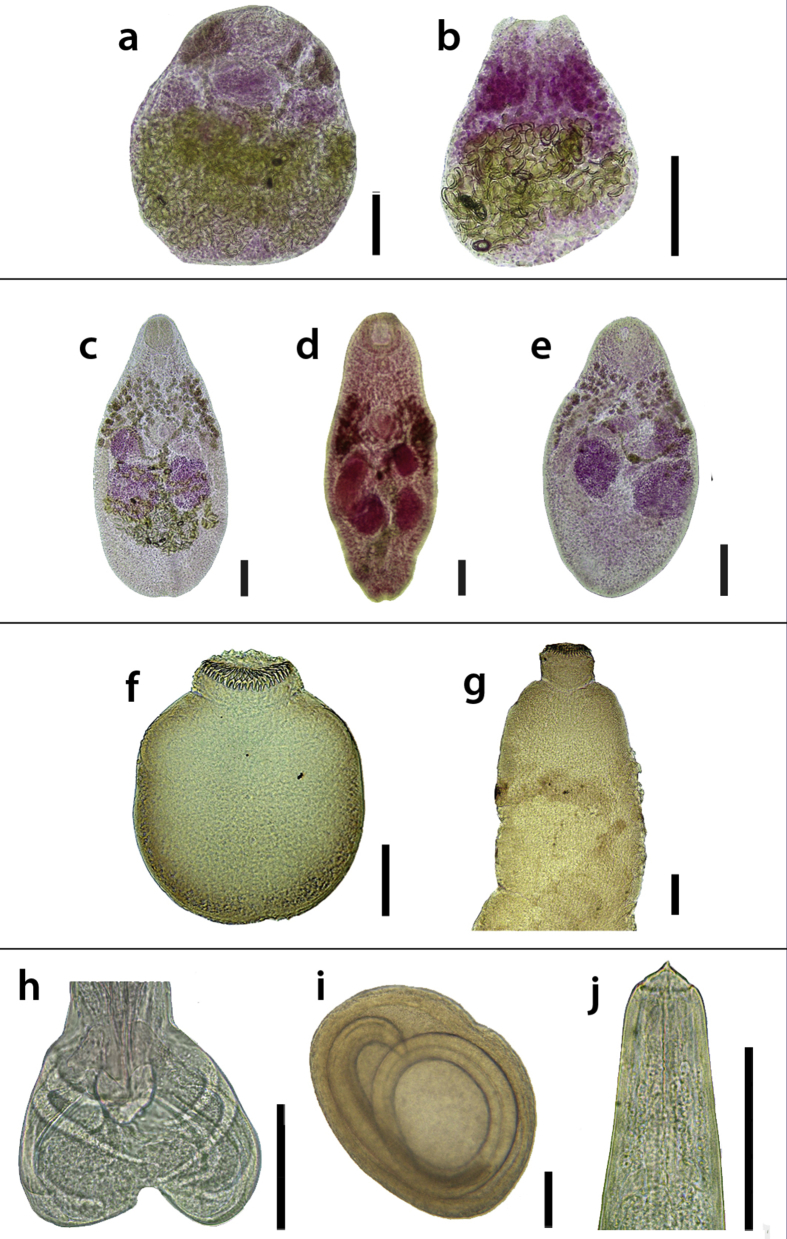

A total of 697 helminths was recovered from 33 bats: five species of trematodes, Ochoterenatrema sp. (Lecithodendriidae), Paralecithodendrium sp. (Lecithodendriidae), Parabascus limatulus (Braun, 1900) (Phaneropsolidae), Parabascus sp. (Phaneropsolidae), and Postorchigenes cf. joannae (Zdzitowiecki, 1967) (Phaneropsolidae), two species of cestodes, Vampirolepis sp. 1 and Vampirolepis sp. 2 (Hymenolepididae), and three species of nematodes, A. baudi (Trichostrongyloidea), Physocephalus sp. (Spiruroidea), and Physaloptera sp. (Physalopteroidea) (Fig. 2). All the species of helminths, but the larvae of Physocephalus sp., which was found encysted in the peritoneum, were recovered from the small and large intestine (Fig. 3). A total of 103 parasites were found detached from the host, and the site of infection could not be specified. The total number of worms, the abundance, the prevalence, and the mean intensity of each helminth species in both component communities are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Endoparasites of Myotis chiloensis. a. Ochoterenatrema sp. (ventral view), b. Paralecithodendrium sp. (ventral view), c. Parabascus limatulus (ventral view), d. Parabascus sp. (dorsal view), e. Postorchigenes cf. joannae (dorsal view), f. Vampirolepis sp. 1 (scolex), g. Vampirolepis sp. 2 (scolex), h. Allintoshius baudi (male's bursa), i. Physocephalus sp. (encysted larvae), j. Physaloptera sp. (anterior region). Scale bar = 100 μm.

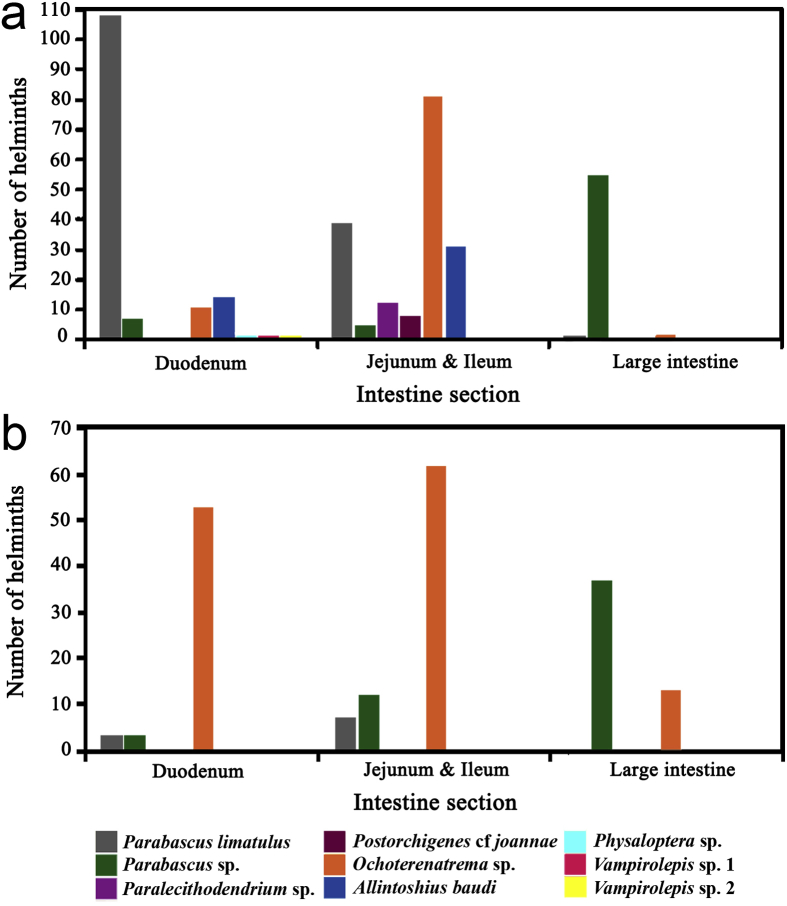

Fig. 3.

Intestinal location of the endoparasites of Myotis chiloensis, represented by the number of helminths found infecting each intestinal region from the bats from a. Manso, b. Luis Ruiz.

Table 2.

Comparison of the population parameters between the two sampling localities. IH: Infested hosts; N: Total of bats; A = Abundance; P%: Prevalence; CI: Confidence interval for the prevalence; MI: Mean intensity.

| Manso |

Luis Ruiz |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IH/N | A | P% | CI | MI | IH/N | A | P% | CI | MI | |

| Trematoda | ||||||||||

| Ochoterenatrema sp. | 9/16 | 103 | 56% | 0.81 | 11.4 | 8/26 | 154 | 32% | 0.34 | 19.3 |

| Paralecithodendrium sp. | 3/16 | 12 | 19% | 0.38 | 4.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Parabascus limatulus | 10/16 | 159 | 63% | 0.86 | 15.9 | 6/26 | 10 | 24% | 0.40 | 1.7 |

| Parabascus sp. | 10/16 | 101 | 63% | 0.86 | 10.1 | 8/26 | 69 | 32% | 0.50 | 8.6 |

| Postorchigenes cf. joannae | 2/16 | 8 | 13% | 0.29 | 4.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cestoda | ||||||||||

| Vampirolepis sp. 1a | 1/16 | 1 | 6% | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Vampirolepis sp. 2a | 1/16 | 1 | 6% | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Nematoda | ||||||||||

| Allintoshius baudi | 12/16 | 48 | 75% | 0.96 | 4.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Physaloptera sp. | – | – | – | – | – | 1/26 | 1 | 4% | 0.12 | 1 |

| Physocephalus sp. | 7/16 | 16 | 44% | 0.68 | 2.3 | 5/26 | 14 | 19% | 0.34 | 2.8 |

Immature proglottids were found in the host with the scolex.

Only two associations were significant: the association between the trematodes Parabascus limatulus and Parabascus sp., which showed the highest value of association (0.90, t = 3.05) in Manso, and the association between Ochoterenatrema sp. and P. limatulus (0.84, t = 2.45). The nematode A. baudi also presented significant associations when paired with trematodes: with Ochoterenatrema sp. the Fager's index value was 0.76 (t = 2.05), with P. limatulus was 0.82 (t = 2.56) and with Parabascus sp. was 0.73 (t = 1.72).

3.2. Comparison of the component communities

The richness of parasite species was higher in Manso (nine species) than in Luis Ruiz (five species), and was significantly different between localities (U = 74, p = .0005). The expected species richness in Manso was slightly higher than the observed in Manso (ChaoManso = 10.88 ± 3.52, JackkLuis Ruiz = 10.88 ± 1.33). Meanwhile, the number of observed species richness and the expected were similar in Luis Ruiz (ChaoManso = 5.00 ± 0.43, JackkLuis Ruiz = 5.96 ± 0.96). The Jaccard index showed that both bat populations share almost half of the endoparasite species (0.45). The diversity indexes indicated that none of the component communities was dominated by a particular species (DManso = 0.19, J'Manso = 0.52; DLuis Ruiz = 0.35, J'Luis Ruiz = 0.47).

3.3. Distribution of the helminths within the hosts

Differences in the abundances among the intestinal regions were found in some species of trematodes in the bats from Manso. Three species of trematodes showed significantly different abundances: P. limatulus (H[2] = 15.8315, p = .0004), which infected mainly the duodenum (Fig. 3a), Ochoterenatrema sp. (H[2] = 7.6357, p = .0220) located mainly in the middle intestine (Fig. 3a), and Parabascus sp. (H[2] = 10.7617, p = .0046) in the large intestine. There were no differences in the abundances among the intestinal sections found for these species of trematodes in Luis Ruiz.

4. Discussion

4.1. Species composition

This is the first survey of M. chiloensis’ helminth fauna. All the species, but A. baudi, represent new records of helminths in Patagonian bats.

4.1.1. Trematodes

Two of the species of trematodes belong to the Lecithodendriidae family and three to the Phaneropsolidae family. Specimens of the first family belong to the genus Ochoterenatrema and Paralecithodendrium. There are five species of the genus Ochoterenatrema parasitizing bats all around the world (Cain, 1966, Odening, 1969, Castiblanco and Vélez, 1982, Lotz and Font, 1983, Lunaschi, 2002a, Lunaschi, 2002b, Milano, 2016) and Ochoterenatrema labda was the only species registered previously in Argentina (Lunaschi, 2002a, Lunaschi, 2002b, Milano, 2016). The specimens found during this study were placed in this genus due to their ventral sucker slightly smaller than the oral sucker, the pseudogonotyl to the left of the ventral sucker, the testes at the level of the ventral sucker and the pseudocirrus-sac between the intestinal bifurcation and the ventral sucker (Lotz and Font, 2008a). However, the trematodes found in M. chiloensis have morphological differences with the other species of the genus. The main differences between Ochoterenatrema sp. from M. chiloensis and O. labda is the spinous tegument and the ovary, which is entire in our specimens. The combination of these characteristics suggests that Ochoterenatrema sp. would be a new species. There are two previous records of Paralecithodendrium species in Argentina: Paralecithodendrium conturbatum and Paralecithodendrium aranhai, parasitizing bats from Buenos Aires province (Lunaschi and Drago, 2007, Milano, 2016). The specimens found in our survey were assigned to this genus due to the position of their testes, which is at the same level of the ventral sucker (Lotz and Font, 2008a). Nevertheless, a further identification was impossible due to the bad condition of the specimens. Both the records of Ochoterenatrema sp. and Paralecithodendrium sp. extend the genus distribution to the South and they are recorded for the first time in bats of the genus Myotis in Argentina.

Regarding the phaneropsolid trematodes, two species were assigned to the genus Parabascus due to their long caeca, which extend posterior to the testes, the cirrus-sac oriented anteriorly, the submedian genital pore and the vitellarium covering the region from the pharynx to the ventral sucker (Lotz and Font, 2008b). As far as we know, there are six previously described species of the genus (Kochseder, 1968, Khotenovsky, 1972, Marshall and Miller, 1979, Lunaschi, 2004, Kirillov et al., 2012). Some specimens were identified as Parabascus limatulus (Braun, 1900). This species was previously re-described based on one specimen found parasitizing Tadarida brasiliensis in the province of Buenos Aires by Lunaschi (2004), who described the caeca as short. Some of the specimens found in this study resemble that of Lunaschi (2004), except in the length of the caeca, which is why we adopt the diagnosis of the Parabascus genus sensu Lotz and Font (2008b), who characterize the caeca as long. The rest of the specimens fit in the genus Parabascus sensu Lotz and Font (2008b), but have a unique cirrus-sac. This feature and the combination of other features such as the relation between the diameters of the suckers, the ovary and testes' position and the vitellarium's distribution suggest that Parabascus sp. found in this study would be a new species. Posthorchigenes cf. joannae specimens resemble the species Posthorchigenes joannae sensu Zdzitowiecki (1967), recorded for the first time parasitizing the bat Myotis daubentoni in Poland (Zdzitowiecki, 1967). The specimens found in our survey were assigned to this genus due to the length of their caeca, posterior to the testes; the cirrus-sac oriented posteriorly and near to the ventral sucker, the submedian genital pore, the submedian ovary at the same level than the ventral sucker, and the vitellarium extending through the anterior region (Lotz and Font, 2008b). Posthorchigenes cf. joannae shows a cirrus-sac elongated, mostly posterior to the ventral sucker, and the genital pore is at the end of the cirrus-sac. The taxonomic results of this work represent the first record of Parabascus species infecting Patagonian bats, the first record of P. limatulus parasitizing a Myotis bat in Argentina, and the first record of a species of the genus Postorchigenes in Argentina.

4.1.2. Cestodes

There are previous records of species of cestodes of the genus Vampirolepis infecting chiropterans belonging to the Molossidae, Phyllostomidae and Vespertilionidae families (Boero and Delpietro, 1970, Milano, 2016). The two species found in this study fit in Vampirolepis due to their armed scolex with fraternoid hooks (Vaucher, 1992). Despite the fact that the anatomy of the mature proglottids are needed in order to identify the species, a preliminary differentiation between other Argentinean species and the ones found in this study was carried out using the number of the rostellum's hooks. Vampirolepis sp. 1 has the same number of hooks as Vampirolepis sp. 2, however, they differ in the shape and measurements of the scolex, the sizes of the suckers and the hook's morphology. This study reports two species of the genus parasitizing bats of the genus Myotis in Argentina for the first time, increasing the host range and the distribution range of the Vampirolepis species.

4.1.3. Nematodes

This study reports three species of nematodes: A. baudi (Ornithostrongylidae), Physaloptera sp. (Physalopteridae), and Physocephalus sp. (Spirocercidae). There are species of nematodes belonging to 12 genera recorded in Argentinean bats from the provinces of Misiones, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Buenos Aires, Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, and Chubut. Only three are found infecting Myotis bats (Vaucher and Durette-Desset, 1980, Ramallo et al., 2007, Oviedo et al., 2009). Our specimens of A. baudi resemble the specimens found by Vaucher and Durette-Desset (1980) parasitizing M. aelleni. They belong to the genus due to the shape of the rays six and eight of the male's bursa and the size of the synlophe, being the ventral ridges bigger than the dorsal ones (Rossi and Vaucher, 2002). The genus Physaloptera was registered previously infecting the bat Eptesicus furinalis in the province of Entre Ríos (Oviedo et al., 2009). The specimen found in M. chiloensis was assigned to this genus due to the presence of a cephalic collarette. This is the second record of a juvenile stage of a Physaloptera nematode infecting Argentinean bats. The nematode larvae found encysted in the peritoneum resembles the species of the genus Physocephalus (Diesing, 1861). The L3 of this genus has an esophagus divided in a muscular and glandular region, which extends beyond the middle of the body and in the posterior end they present two concentric rings with digitiform processes (Alicata, 1935). Up to date, there were no records of larval stages of nematodes from bats in Argentina. The presence of Physocephalus L3 encysted in the peritoneum indicates that M. chiloensis can play the role of an intermediate host for this species. Owls (Tyto alba) and domestic cats were observed attacking and feeding on T. brasiliensis bats in the city of Rosario, Argentina (Romano et al., 1999). The life cycle of the Physocephalus L3 might continue in any of these animals in the Patagonia.

4.2. Community structure

4.2.1. Associations between species

The highest association value was between the two species belonging to the Parabascus genus. Despite the fact that the association values of Ochoterenatrema sp. with P. limatulus and Parabascus sp. were high in the bats from both localities, only the association between Ochoterenatrema sp. and P. limatulus was statistically significant. These values might indicate that these trematodes share a common intermediate host. The associations between gastrointestinal helminths from a definitive host could be reflecting the interactions between the species infecting the intermediate host (Poulin, 2001). Metacercariae (Mariluan et al., 2012) and larvae of cestode (Pers. Obs.) have been found in nymphs (Order Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Diptera, and Trichoptera) from Patagonian streams. In contrast to the trematodes, which have heteroxenous cycles, trychostrongyloid nematodes have monoxenous cycles, and the infectation happens when the bat ingests the eggs (Anderson, 1988, Anderson, 2000). Therefore, the high association values between A. baudi and the three species of trematodes could be explained by two factors. On one hand, the Fager's Index is sensitive to the number of infected hosts by the endoparasite species. Allintoshius baudi was found infecting most of the bats from Manso, which might explain the high association values with the trematodes. On the other hand, it might be due to facilitation processes. Allintoshius baudi could be inducing a bat's immunosuppression, benefiting the infectation by other species of endoparasites (Poulin, 2001).

4.3. Comparison between component communities

The differences in the species richness between Manso and Luis Ruiz could be due to differences in the environments, which imply differences in the bat's diet. The environments studied show differences in the humidity, vegetation, abundance, and type of waterbodies, reflecting the differences between forest and ecotone (Raffaele et al., 2014). The site Manso is located in the Andean forest, near the Manso Inferior river and the numerous flood areas around it, whereas the Luis Ruiz site is located in the ecotone between the forest and the steppe, near a small, shallow, bog lake. In general, lakes with the latter characteristics, as also lentic environments, support lower species richness of insects than lakes from forests or lotic environments (Heino, 2009, Hanson et al., 2010). The small shallow lake located in Luis Ruiz probably have a lower diversity of insects with naiads in their life cycle. Insects intervene as intermediate hosts in the life cycles of many species of endoparasite infecting chiropterans (Hilton and Best, 2000). Due to the fact that Manso shows higher quantity of waterbodies than Luis Ruiz, and presents an heterogeneous bottom of inorganic and organic material, and therefore, a higher insect diversity, it is expected that the bats from this locality would have high values of species richness. Both species richness estimators suggest that the expected number of species is approximately 11 in Manso and five in Luis Ruiz. Two of the species found parasitizing the bats in Manso were rare species (Vampirolepis sp. 1 and sp. 2), represented by one individual each. It could be expected that the 11th species in this locality would be a rare species, too.

Both of the endoparasite communities from the M. chiloensis populations share approximately half of the species, being trematodes the majority. This could be explained by the presence of common intermediate hosts in both sites. On the other hand, the ecological indexes calculated suggest that there is no dominant endoparasite species. However, it should be noted that the highest abundance and prevalence values belong to three species of trematodes (Ochoterenatrema sp., P. limatulus, and Parabascus sp.), in contrast to the other helminths.

4.4. Preferences for intestinal regions

Intestinal helminths may show a preference for the site of attachment in the host's gut. However, interactions among species may result in an alteration of the site of attachment (Poulin, 2001). Ochoterenatrema sp, P. limatulus, and Parabascus sp. were found parasitizing the three intestinal regions in Manso. Nevertheless, different preferences appeared for each trematode: Ochoterenatrema sp. occupied preferably the small intestine, P. limatulus the duodenum, and Parabascus sp. the large intestine. There are different factors that could be affecting the distribution of the endoparasites along the intestine, such as specialization, reproductive efficiency and competition. Due to negative interactions between species, one species of parasite may alter their distribution in order to minimize the spatial overlap with the others (Poulin, 2001). Interspecific competition is one of the main factors delimiting the fundamental niche of one parasite species (Holmes, 1990). On the other hand, none of the trematodes species showed a preference for the intestinal regions in Luis Ruiz, probably because the trematodes' abundance and intensity were lower than in Manso. Interespecific competition depends on the intensities of the species that are interacting, which means that in small endoparasite infrapopulations this kind of competition would not be significant (Dobson, 1985). It should be noted that Ochoterenatrema sp. was the most abundant species in both the duodenum and the small intestine, unlike in Manso. This could be explained by the low quantity of P. limatulus in the duodenum. When the numbers are high for P. limatulus, these two species could be interacting negatively, as seen in Manso.

The role of insectivorous bats in the ecosystem is highly important, due to their role as both definitive and, more rarely, intermediate host, seen in the large number of parasite species found infecting bat populations (Boero and Delpietro, 1970, Saoud and Ramadan, 1976, Esteban et al., 2001, Lunaschi and Drago, 2007, Fugassa, 2015, Portes Santos and Gibson, 2015, Milano, 2016, Clarke-Crespo et al., 2017, Esteban et al., 1999, Esteban et al., 2001, Shimalov et al., 2002), and M. chiloensis is not the exception to this. Due to their endoparasites, these bats could be acting as a link between the aquatic and terrestrial environments, allowing the exchange of matter and energy. Nevertheless, little is known about the diversity of endoparasites in Neotropical bats, and about a third of the known bats have been studied in this matter in South America (Portes Santos and Gibson, 2015). The species reported in this study provide useful information and contribute to the actual knowledge on bat's helminth fauna, by reporting for the first time the parasite diversity in a poorly studied bat species, M. chiloensis, and extending the distributions of several known endoparasite genus to the South of the continent.

Acknowledgements

Funds were provided by the Project B-187 of the Universidad Nacional del Comahue. We thank Dr. Richard Sage for providing the material for this study, for the critical reading, and the idiomatic corrections of the manuscript. The permissions for the project “Estudio de fauna de pequeños vertebrados (anfibios, reptiles and mamíferos) en el Oeste de la provincia de Río Negro”, were provided by Dirección de Fauna Silvestre – Ministerio de Producción (Provincia de Río Negro) N° 134275 –DFS– 2006. We also thank Prof. Norma Brugni, for the help in the determination of the nematodes of this study, and Dr. Gilda Garibotti, for the help with the statistics.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.12.004.

Contributor Information

Antonella C. Falconaro, Email: anto.falconaro@gmail.com.

Rocío M. Vega, Email: rvega@comahue-conicet.gob.ar.

Gustavo P. Viozzi, Email: gustavo.viozzi@crub.uncoma.edu.ar.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Alicata J.E. Early developmental stages of Nematodes occurring in swine. Tech. Bull. 1935;489:1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.C. Nematode transmission patterns. J. Parasitol. 1988;74:30–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.C. 2° Ed. CABI Publishing; Wallingford, Oxon, Reino Unido: 2000. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. Their Development and Transmission. [Google Scholar]

- Barquez R.M., Carbajal M.N., Failla M., Díaz M.M. New distributional records for bats of the Argentine Patagonia and the southernmost known record for a molossid bat in the world. Mamm. 2013;77:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Barquez R.M., Díaz M.M. PCMA Publicaciones especiales; Magma. Tucumán: 2009. Los murciélagos de Argentina. Clave de identificación (Key to the Bats of Argentina) [Google Scholar]

- Boero J.J., Delpietro H. 1970. El parasitismo de la fauna autóctona. VII. Los parásitos de los murciélagos argentinos. Jornadas Internas de la Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias. La Plata, Argentina; pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. Vol. 15. 1900. pp. 217–237. (Trematoden der Chiroptera). Annalen des K.K. Naturhist. Hofmuseums. [Google Scholar]

- Bush A.O., Lafferty K.D., Lotz J.M., Shostak A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997;83:575–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain G.D. Helminth parasites of bats from Carlsbad caverns, New Mexico. J. Parasitol. 1966;52:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Castiblanco F., Vélez I. Observación de trematodos digenéticos en murciélagos del Valle de Aburra y alrededores. Actual. Biol. 1982;11:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke-Crespo E., de León G.P., Montiel-Ortega S., Rubio-Godoy M. Helminth fauna associated with three Neotropical bat species (Chiroptera: mormoopidae) in Veracruz, México. J. Parasitol. 2017;103:338–342. doi: 10.1645/16-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover W.J. 2° Ed. Texas Tech University; Estados Unidos: 1980. Practical Nonparametric Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz M.M., Aguirre L.F., Barquez R.M. Centro de Estudios en Biología Teórica y Aplicada; Bolivia: 2011. Clave de identificación de los murciélagos del Cono Sur de Sudamérica. [Google Scholar]

- Diesing K.M. Vol. 42. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien; 1861. pp. 595–763. (Revision der Nematoden). Kaiserl. [Google Scholar]

- Drago F.B., Lunaschi L.I., Delgado L., Robles R. 2007. Helmintofauna de quirópteros de la Reserva Natural Punta Lara, Provincia de Buenos Aires. Resúmenes: XXI Jornadas de Mastozoología. Tucumán, Argentina; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson A.P. The population dynamics of competition between parasites. Parasitology. 1985;91:317–347. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000057401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban J.G., Amengual B., Serra Cobo J. Composition and structure of helminth communities in two populations of Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) from Spain. Folia Parasitol. 2001;48:143–148. doi: 10.14411/fp.2001.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban J.G., Botella P., Toledo R., Oltra-Ferrero J.L. Helminthfauna of bats in Spain. IV. Parasites of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (schreber, 1774) (chiroptera: rhinolophidae) Res. Rev. Parasitol. 1999;59:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fager E.W. Determination and analysis of recurrent groups. Ecology. 1957;38:586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Fugassa M.H. Checklist of helminths found in Patagonian wild mammals. Zootaxa. 2015;4012:271–328. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4012.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez A.L., Giannini N.P. 2013. Primeros registros de los hábitos dietarios de cinco especies de murciélagos patagónicos (Chiroptera: Vespertillionidae). XXVI Jornadas Argentinas de Mastozoología.Esquel, Argentina. 190 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P., Springer M., Ramirez A. Introducción a los grupos de macroinvertebrados acuáticos. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2010;58:3–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino J. Biodiversity of aquatic insects: spatial gradients and environmental correlates of assemblage-level measures at large scales. Fr. Rev. 2009;2:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton C.D., Best T.L. 2000. Gastrointestinal Helminth Parasites of Bats in Alabama. Occasional papers of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and North Carolina Biological Survey; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J.C. Competition, contacts, and other factors restricting niches of parasitic helminths. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1990;65:69–72. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1990651069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khotenovsky I.A. On the evolution of trematodes from bats. Parazitologiia. 1972;6:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov A.A., Kirillova N.Y., Vehknik V.P. Trematodes (trematoda) of bats (chiroptera) from the middle volga region. Parazitologiia. 2012;46:384–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochseder V.G. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 1968. Untersuchungen über Trematoden und Cestoden aus Fledermäusen in der Steiermark; pp. 206–232. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C.J. Harper Collins Publishers; New York: 1989. Ecological Methodology. [Google Scholar]

- Lord J.S., Parker S., Parker F., Brooks D.R. Gastrointestinal helminths of pipistrelle bats (Pipistrellus pipistrellus/Pipistrellus pygmaeus) (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) of england. Parasitology. 2012;139:366–374. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz J.M., Font W.F. Review of the Lecithodendriidae (trematoda) from Eptesicus fuscus in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Proc. Helm. Soc. Wash. 1983;50:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz J.M., Font W.F. Family Lecithodendriidae. Mehra, 1935. In: Bray R.A., Gibson D.I., Jones A., editors. vol. 3. CAB International and Natural History Museum; London: 2008. pp. 527–543. (Keys to Trematoda). [Google Scholar]

- Lotz J.M., Font W.F. Family Phaneropsolidae Mehra, 1935. In: Bray R.A., Gibson D.I., Jones A., editors. vol. 3. CAB International and Natural History Museum; London: 2008. pp. 545–562. (Keys to Trematoda). [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I. Redescripción y comentarios taxonómicos sobre Ochoterenatrema labda (Digenea: Lecithodendriidae), parásito de quirópteros de México. Anales Inst. Biol. Univ. Nac. Autón. Méx., Ser. Zool. 2002;73:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I. Tremátodos Lecithodendriidae y Anenterotrematidae de Argentina, México and Brasil. Anales Inst. Biol. Univ. Nac. Autón. Méx., Ser. Zool. 2002;73:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I. Redescripción de Limatuloides limatulus (Braum) Dubois, 1964 (Trematoda, Lecithodendriidae), un parásito de Tadarida brasilensis (geof.) (Chiroptera, Molossidae) de Argentina. Gayana. 2004;68:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I. Redescripción and reubicación sistemática del trematodo Topsiturvitrema verticalia (Trematoda: digenea) en una familia nueva. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2006;54:1041–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I., Drago F. Checklist of digenean parasites of wild mammals from Argentina. Zootaxa. 2007;1580:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I., Notarnicola J. New host records for Anenterotrematidae, Lecithodendriidae and Urotrematidae trematodes in bats from Argentina, with redescription of Anenterotrema liliputianum. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2010;81:281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lunaschi L.I., Urriza M., Merlo Alvarez V.H. Limatulum oklahomense Macy, 1932 in Myotis nigricans (Chiroptera) from Argentina and a redescription of L. umbilicatum (Vélez et Thatcher, 1990) comb. nov. (Digenea, Lecithodendriidae) Acta Parasitol. 2003;48:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mariluan G.D., Viozzi G.P., Albariño R.J. Trematodes and nematodes parasitizing the benthic insect community of an Andean Patagonian stream, with emphasis on plagiorchiid metacercariae. Invertebr. Biol. 2012;131:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M.E., Miller G.C. Some digenetic trematodes from ecuatorian bats including five new species and one new genus. J. Parasitol. 1979;65:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- Milano A.M.F. Universidad Nacional de La Plata; La Plata, Argentina: 2016. Helmintofauna de murciélagos (Chiroptera) del Nordeste argentino. Tesis de doctorado. [Google Scholar]

- Odening K. Exkretions system und systematische Stellung Kubanischer Fledermaustrematoden. Bijdr. Dierk. 1969;39:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ossa G., Rodríguez San Pedro A. Myotis chiloensis (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) Mamm. Species. 2015;47:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo M.C., Ramallo G., Claps L. Universidad Nacional de Tucumán; Tucumán, Argentina: 2009. Nemátodos parásitos de Murciélagos (Mammalia: Chiroptera) de Entre Ríos, Argentina. Serie Monográfica and Didáctica Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo M.C., Ramallo G., Claps L. Una nueva especie de Cheiropteronema (Nematoda, Molineidae) en Artibeus planirostris (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) en la Argentina. Iheringia. Serie Zoologia. 2010;100:242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo M.C., Notarnicola J., Miotti M.D., Claps L.E. Emended description of Litomosoides molossi (Nematoda: onchocercidae) and first records of Litomosoides species parasitizing Argentinean bats. J. Parasitol. 2016;102:440–450. doi: 10.1645/15-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo M.C., Ramallo G., Claps L., Miotti M.D. A new species of Biacantha (Nematoda: molineidae), a parasite of the common vampire bat from the Yungas, Argentina. J. Parasitol. 2012;98:1209–1215. doi: 10.1645/GE-3155.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Santos C., Gibson D.I. Checklist of the helminth parasites of South american bats. Zootaxa. 2015;3937:471–499. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3937.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R. Interactions between species and the structure of helminth communities. Parasitology. 2001;122:S3–S11. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000016991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele E., Torres Curth M., Morales C.L., Kitzberger T. 1° Ed. Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara; Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina: 2014. Ecología e historia natural de la Patagonia andina: un cuarto de siglo de investigación en biogeografía, ecología y conservación. 256 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Ramallo G., Oviedo M., y Claps L.E. 2007. Nematofauna parásita de quirópteros de la Provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina: Informe Preliminar. Resúmenes: XXI Jornadas de Mastozoología. Tucumán, Argentina. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Romano M.C., Maidagan J.I., Pire E.F. Behavior and demography in an urban colony of Tadarida brasiliensis (chiroptera: Molossidae) in Rosario, Argentina. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1999;47:1121–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P., Vaucher C. Allintoshius bioccai n. sp. (Nematoda), a parasite of the bat Eptesicus furinalis from Paraguay, and new data on A. parallintoshius (Araujo, 1940) Parassitologia. 2002;44:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saoud M.F.A., Ramadan M.M. Studies on the helminth parasites of bats in Egypt and the factors influencing their occurrence with particular reference to digenetic trematodes. Z. für Parasitenkd. 1976;51:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shimalov V.V., Demyanchik M.G., Demyanchik V.T. A study on the helminth fauna of the bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in Belarus. Parasitol. Res. 2002;88:1011. doi: 10.1007/s004360100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucher C. Revision of the genus Vampirolepis spasskij, 1954 (cestoda: hymenolepididae) Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Vaucher C., Durette-Desset M.C. Allintoshius baudi n. sp. (Nematoda: trichostrongyloidea) parasite du Murin Myotis aelleni Baud, 1979 et redescription de A. tadaridae (Caballero, 1942) Rev. Suisse Zool. 1980;87:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal H., Álvarez M., Córdoba S., Escobar F., Fagua G., Gast F., Mendoza H., Ospina M., Umaña A.M. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt; Bogotá, Colombia: 2006. Manual de métodos para el desarrollo de inventarios de biodiversidad. Programa de Inventarios de Biodiversidad. [Google Scholar]

- Zdzitowiecki K. Czosnowia joannae g. n. sp. n. (Lecithodendriidae), a new trematodes species from the bat, Myotis daubentoni (Kühl, 1819) Acta Parasitol. Pol. 1967;31:405–408. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.