Abstract

Objective

To determine the clinical effectiveness of pressurised metered dose inhalers (with or without spacer) compared with other hand held inhaler devices for the delivery of corticosteroids in stable asthma.

Design

Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources

Cochrane Airways Group trials database (Medline, Embase, Cochrane controlled clinical trials register, and hand searching of 18 relevant journals), pharmaceutical companies, and bibliographies of included trials.

Trials

All trials in children or adults with stable asthma that compared a pressurised metered dose inhaler with any other hand held inhaler device delivering the same inhaled corticosteroid.

Results

24 randomised controlled trials were included. Significant differences were found for forced expiratory volume in one second, morning peak expiratory flow rate, and use of drugs for additional relief with dry powder inhalers. However, either these were within clinically equivalent limits or the differences were not apparent once baseline characteristics had been taken into account. No significant differences were found between pressurised metered dose inhalers and any other hand held inhaler device for the following outcomes: lung function, symptoms, bronchial hyper-reactivity, systemic bioavailability, and use of additional relief bronchodilators.

Conclusions

No evidence was found that alternative inhaler devices (dry powder inhalers, breath actuated pressurised metered dose inhalers, or hydrofluoroalkane pressurised metered dose inhalers) are more effective than the pressurised metered dose inhalers for delivery of inhaled corticosteroids. Pressurised metered dose inhalers remain the most cost effective first line delivery devices.

What is already known on this topic

Many inhaler devices are available for administering inhaled corticosteroids

Current guidelines for their use are inconsistent and not evidence based

What this study adds

This systematic review found no evidence that alternative inhaler devices are more effective than pressurised metered dose inhalers for giving inhaled corticosteroids.

Pressurised metered dose inhalers (or the cheapest device) should be first line treatment in all patients with stable asthma

Introduction

Numerous inhaler devices and drug combinations are now available for delivering inhaled corticosteroids in patients with asthma. These include breath actuated pressurised metered dose inhalers, dry powder devices, and chlorofluorocarbon-free or hydrofluoroalkane pressurised metered dose inhalers. The cost of the drug used in specific devices varies widely, but there are no explicitly evidence based guidelines on which are the most effective. We conducted a systematic review to determine the clinical effectiveness of the standard chlorofluorocarbon containing pressurised metered dose inhaler versus other hand held inhaler devices in delivering corticosteroids to patients with stable asthma.

Methods

Identification and selection of trials

We identified trials published from 1966 to July 1999 by computerised searches of the Cochrane Airways Group trials database, which includes Medline, Embase, CINAHL, hand searching of 18 relevant journals and proceedings of three respiratory societies, and review of the bibliographies of included trials (see www.ncchta.org/execsumm/summ526.htm). We included citations in any language. We also contacted the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture inhaled asthma drugs and searched the reference lists of included trials for further studies.

The results of the computerised search were independently reviewed by two reviewers. Any potentially relevant articles were obtained in full. The full text of potentially relevant articles was reviewed independently by the two reviewers. Disagreement was resolved by third party adjudication.

We considered only randomised controlled trials in children or adults that were laboratory, hospital, or community based and lasted for four weeks or longer. Trials were included if they compared clinical outcomes of a single drug delivered by standard pressurised metered dose inhaler (with or without a spacer device) versus any other hand held inhaler device. Trials comparing different doses of the same drug were included.

We included the following outcomes: lung function, quality of life measures, symptom scores, drugs for additional relief, acute exacerbation, days off work or school, treatment failure, patient compliance, patient preference, adverse effects, bronchial hyper-reactivity, and systemic bioavailability.

Data abstraction and assessment of validity

Details of each trial (intervention, duration, participants, design, quality, and outcome measures) were extracted independently by the two reviewers directly into tables. Disagreement was resolved by consensus. We contacted first authors of the included studies as necessary to provide additional information or data for their studies. We assessed the internal validity of included trials using the Cochrane scale.1

Analysis of data

We analysed data using Review Manager (RevMan, Version 4.1) statistical software.1 For the meta-analysis, we used weighted mean differences for outcomes using the same measures on continuous scales (for example, forced expiratory flow in one second) or standardised mean differences for outcomes that used different scales (for example, forced expiratory flow in one secondabsolute and improvement from baseline).

The pressurised metered dose inhaler was compared with each other hand held inhaler device separately. Each of these device comparisons was further separated into the different trial designs—that is, crossover and parallel. Trials were analysed separately for children and adults.

We tested for heterogeneity between trials using χ2 tests. If statistical heterogeneity was not found, a fixed effects model was used with 95% confidence intervals. If heterogeneity occurred, subgroup analyses were planned beforehand to explore possible reasons for heterogeneity. These subgroups included trial quality, severity of asthma, type of corticosteroid, and use of spacer device with pressurised metered dose inhaler.

Results

The electronic search yielded 783 citations. An additional six references were added from searching the bibliographies of included trials and one study, which was in press, was identified by contacting pharmaceutical companies (fig 1). From the 790 abstracts, 39 trials were identified by two reviewers as potentially suitable for inclusion. After scanning the full text of these 39 trials, we excluded 15 (see www.ncchta.org/execsumm/summ526.htm for details). Disagreements over inclusion arose in three papers and were resolved after discussion with the third reviewer. Twenty four papers were included in the review. These covered a total of 29 studies because one paper reported two separate trials,2 one had three parallel arms and a dose comparison,3 and another was part of a three way crossover trial.4 Full details of the included studies are available on www.ncchta.org/execsumm/summ526.htm. We wrote to authors of 23 of the included trials for further information and received seven replies.

Figure 1.

QUORUM trial flow results

Data synthesis

All trials were adequately randomised, with six having Cochrane grade A for concealment of allocation and 19 having grade B. No data were available for quality of life scores or days off work or school.

We analysed the results in three categories for adults: pressurised metered dose inhaler versus dry powder inhaler, pressurised metered dose inhaler versus hydrofluoroalkane pressurised metered dose inhaler, and pressurised metered dose inhaler versus breath actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler. A separate analysis was performed for trials in children. A complete set of Forrest plots is available on www.ncchta.org/execsumm/summ526.htm.

Thresholds for clinically important results of pulmonary function tests are often arbitrary. However, from the range of values that the trial researchers used, a guide would be 15-30 l/min or 7.5% to 20% for peak expiratory flow rate and 0.2 litres or 15% for forced expiratory volume in one second.

Pressurised metered dose inhaler versus dry powder inhaler

Thirteen papers comparing pressurised metered dose inhalers with dry powder inhalers described 14 studies.4–16 Fifteen outcomes were available for analysis with a range of three to 14 studies for each outcome. Only patient preference showed any evidence of heterogeneity.

We found significant differences in favour of dry powder inhaler for improving forced expiratory volume in one second, morning peak expiratory flow rate, and use of additional relief drugs in the parallel studies (table 1). No other outcomes showed significant differences (tables 1 and 2 ).

Table 1.

Results for parallel studies comparing pressurised metered dose inhaler with dry powder inhaler. Negative values or relative risk <1 favours dry powder inhaler

| Outcome | No of studies | No of subjects | Statistic | Treatment effect (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 | 7 | 1404 | SMD | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.03) |

| Morning peak expiratory flow rate | 7 | 1389 | SMD | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.04) |

| Use of additional relief drugs | 6 | 967 | SMD | −0.18 (−0.31 to −0.05) |

| FEV1 (l) | 6 | 1120 | WMD | −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.02) |

| Morning peak expiratory flow rate (l/min) | 6 | 1151 | WMD | −10.8 (−21.7 to 0.1) |

| Evening peak expiratory flow rate(l/min) | 5 | 1084 | WMD | −10.2 (−21.4 to 0.1) |

| Symptom score: | ||||

| Cough | 1 | 144 | NA | NA |

| Wheeze | 1 | 144 | NA | NA |

| Breathlessness | 1 | 144 | NA | NA |

| Standardised symptom score | 5 | 703 | SMD | −0.06 (−0.21 to 0.09) |

| Exacerbations | 4 | 816 | Relative risk | 0.88 (0.49 to 1.58) |

| Adverse effects: | ||||

| Serum cortisol (mmol/l) | 6 | 1163 | WMD | 5.01 (−18.3 to 28.2) |

| Hoarse voice | 5 | 1100 | Relative risk | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.41) |

| Oral thrush | 6 | 1386 | Relative risk | 1.44 (0.71 to 2.89) |

| Provocation testing (mg) | 3 | 428 | WMD | −102 (−466 to 262) |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second, SMD=standardised mean difference, WMD=weighted mean difference, NA=not available.

Three studies had significant differences in baseline characteristics7,11,14 for peak expiratory flow rate, forced expiratory volume in one second, symptom scores, or use of relief drugs. In one of these, the dry powder inhaler group had more severe asthma and results were presented as relative change from baseline.7 In the other two studies, the control group (pressurised metered dose inhaler) had more severe asthma and results were presented as absolute values.11,14 The method of data analysis used in all threewas potentially biased in favour of the dry powder inhaler groups.

We used two methods to explore the effect of these baseline differences. Firstly, we excluded them from the analysis. This resulted in the all treatment effects becoming non-significant. Secondly, we used the alternative presentation of results—that is, relative change for two11,14 and absolute values for the other7 (using estimates based on the original data). We found no significant differences in treatment effect for comparisons of forced expiratory volume in one second, peak expiratory flow rate, or use of additional relief drugs.

Patient preference showed marked heterogeneity. This may be because different dry powder inhalers were used in the studies. Two studies used a Rotahaler, which was significantly less preferred to the pressurised metered dose inhaler,5,6 and two used a Turbohaler, which was significantly preferred to pressurised metered dose inhalers.8,13 No data were presented to indicate whether stated patient preference increases compliance in routine daily use.

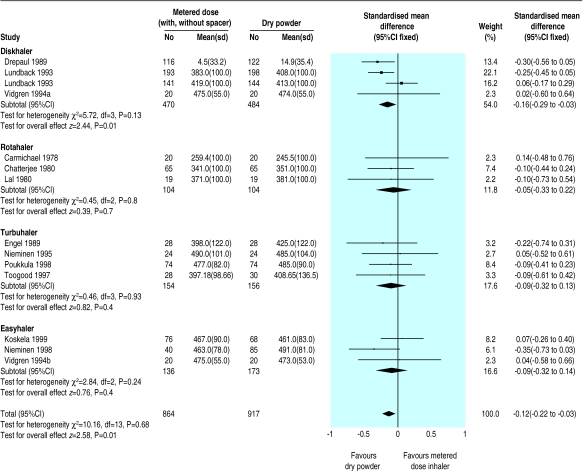

When we analysed outcomes by type of dry powder inhaler (Rotahaler, Turbohaler, Diskhaler, and Easyhaler) we found no significant differences between pressurised metered dose inhaler and dry powder inhaler or between the dry powder inhaler groups except in the case of Diskhaler, which was significantly better (fig 2). This group, however, contained two of the trials with significant baseline differences.7,11

Figure 2.

Comparison of morning peak expiratory flow rate for pressurised metered dose inhalers with and without spacer versus different dry powder inhalers

Analysis of results for pressurised metered dose inhalers used with and without spacer devices separately did not affect the results for dry powder inhalers. However, this indirect subgroup comparison was not determined beforehand and therefore is not a reliable method to assess the usefulness of spacer devices.

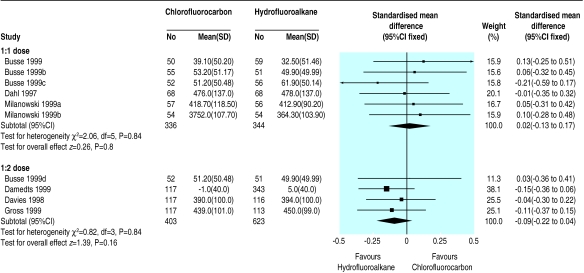

Chlorofluorocarbon versus hydrofluoroalkane pressurised metered dose inhaler

Seven papers describing 11 studies were included.2,3,17–21 Ten studies used beclometasone and one used fluticasone.21 One trial was of crossover design.17 No significant differences in treatment effect were found. Parallel and crossover designs were analysed as subgroups for each outcome, with no significant change in the findings.

Six studies2,3,17 used a 1:1 dosing schedule for beclometasone between hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon inhalers, and four studies3,18–20used a 1:2 schedule. Subgroup analysis showed no significant differences for any outcome between the two devices with either dose ratio (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes for hydrofluoroalkane versus chlorofluorocarbon pressurised metered dose inhalers at 1:1 and 1:2 dose ratios. Negative values or relative risk <1 favours hydrofluoroalkane pressurised devices

| Outcome, dose ratio | No of studies | No of subjects | Statistic | Treatment effect (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1: | ||||

| 1:1 | 6 | 680 | Standardised mean difference | −0.05 (−0.20 to 0.10) |

| 1:2 | 4 | 1000 | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.14) | |

| Peak expiratory flow rate: | ||||

| 1:1 | 6 | 680 | Standardised mean difference | 0.02 (−0.13 to 0.17) |

| 1:2 | 4 | 1026 | −0.09 (−0.22 to 0.04) | |

| Oral thrush: | ||||

| 1:1 | 2 | 238 | Relative risk | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.10) |

| 1:2 | 2 | 463 | 0.51 (0.05 to 5.56) | |

| Hoarse voice (1:2) | 2 | 463 | Relative risk | 1.22 (0.54 to 2.79) |

| Use of relief drugs: | ||||

| 1:1 | 4 | 453 | Standardised mean difference | −0.13 (−0.31 to 0.05) |

| 1:2 | 3 | 566 | 0.05 (−0.12 to 0.21) | |

Breath actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler versus pressurised metered dose inhaler

One study comparing breath actuated inhalers with standard pressurised metered dose inhalers was identified and included.22 This used an “equivalence model” design in which the 90% confidence interval for the difference between the inhalers falls completely within the reference device (pressurised metered dose inhaler) mean response interval (−20% to 20%). Equivalence was shown for all outcomes measured with no significant differences between treatments.

Children

Three studies in children were identified and included.23–25 We could not do a meta-analysis of the results because of differences in the devices and ages compared and lack of extractable data. No study showed any significant differences in pulmonary function between the devices. One study found a reduction in use of relief drugs of 1 puff/week in the Turbohaler group compared with the metered dose inhaler group (95% confidence interval 0.34 to 1.96).23

Discussion

We found no significant differences in measures of pulmonary function, symptom scores, exacerbation rates, and adverse effects between a pressurised metered dose inhaler and other inhalers for the delivery of corticosteroids. Significant differences were found for three outcomes for dry powder inhalers. However, either these were within clinically equivalent limits or the differences were not apparent once baseline characteristics had been taken into account.

Although we found no significant differences for most outcomes in this review, the confidence intervals may include clinically important differences. Our comparison of population means cannot show such clinically important differences for individual patients from different inhaler devices. Small changes in physiological measures such as pulmonary function will not necessarily be important in themselves but rather in the effect they have on the symptoms and quality of life of the patient.26

Potential biases

We found no evidence of systematic publication bias from funnel plots. The lack of any overall significant treatment effects also supports this, although it does not exclude the possibility of equivalence being positive publication bias. All of the included studies had some commercial sponsorship. Potential biases in the conduct and reporting of results are therefore important to consider.

The results of many tests of pulmonary function can be presented in various ways, predominantly as absolute values or a change from baseline (absolute or relative). This may be a source of bias. In the comparison of dry powder inhalers versus pressurised metered dose inhalers, three studies had significant differences between groups at baseline, and the choice of measurement was critical to the outcome of not only the individual studies but of the meta-analysis.

Of the 10 crossover studies we included, none described a washout period between the arms, and this may have led to underestimation of the treatment effect, especially as inhaled corticosteroids have a long duration of action. Five of the 10 studies described tests for carry over effect or combination within an analysis of variance model, but no significant effects were stated. Our meta-analysis treated data as if they were unpaired or parallel, and where possible we analysed crossover and parallel studies separately. First arm data of a crossover trial can be used as a parallel trial, but these data were not available for these studies. Alternatively, crossover studies can be combined and weighted by an inverse variance model if interpatient error is known rather than group mean data. Again, these data were not available.

Doses used

Inhaled corticosteroids have a shallow dose-response curve.27 Dose selection for a study may affect the ability of a trial to detect differences between inhaler devices. Most asthmatic patients require relatively low doses of inhaled steroids to maintain good health (200-800 μg of beclometasone daily—that is, low to moderate doses on step 2 of the British Thoracic Society asthma guidelines).28 Ten of the 20 adult studies used doses of 800 μg daily or greater (assuming fluticasone to be equivalent to twice the dose of budesonide or beclometasone). Such high doses do not reflect usual clinical practice, and using doses at the top of the dose-response curve may bias towards underestimating or missing a treatment difference.

Disease severity

The less severe the disease, the smaller are potential improvements in pulmonary function and symptoms from baseline. Patients in the studies had relatively mild disease, as shown by the low numbers of exacerbations (69 cases from 2065 patients) and very low mean symptom scores and use of additional relief drugs (usually <2 puffs/day). The mean reported forced expiratory volume in one second at baseline was 2.6 (SD 0.42) litres. In seven of the 10 trials that reported severity of asthma at baseline, the grade was mild or mild to moderate. Although this probably reflects “usual” disease of the general population, it will make it harder to detect a treatment effect between inhaler devices.

Duration

Inhaled corticosteroids have a long duration of action and may take weeks or months to reach a plateau of effect. Asthma guidelines suggest titrating doses every one to three months.28 The longest study lasted 12 weeks (11 studies were for four weeks). As the duration of study decreases, the risk of missing a treatment difference increases because the drug may have failed to reach its maximum effect.

Hydrofluoroalkane: chlorofluorocarbon dose ratio

The studies comparing hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon pressurised devices seem to have adequate design and power to show equivalence. However, when the studies were analysed in subgroups according to the dose ratio (1:1 or 1:2) no significant difference was found. Each group of studies (and subsequently marketing and prescribing recommendations) claims that its dose ratio is correct. We found no difference between the two dose ratios, but this may be related to the different delivery characteristics of the hydrofluoroalkane inhalers used.

It is important not to overinterpret this subgroup analysis because it provides only an indirect comparison. On a practical level, a generic prescription for chlorofluorocarbon-free beclometasone could be dispensed as either of two “equivalent” preparations. One will be accompanied by advice that it is twice as potent as the other. There is potential for serious confusion when transferring from chlorofluorocarbon to hydrofluoroalkane inhalers.

Unanswered questions

Further research is required in children and in devices other than dry powder inhalers. Although the primary outcome (respiratory function) may be assumed to have equivalence, adverse effects are much less well reported. As such, there is limited information on which to judge the relative benefits and side effects of different devices. Further systematic reviews are needed to assess the effectiveness of pressurised metered dose inhalers with or without spacer devices and the effectiveness of training and education about use of inhaler devices. Pragmatic studies are also required to see whether long term compliance is influenced by choice of delivery device.

In summary, we found no evidence that alternative inhaler devices are more clinically effective than pressurised metered dose inhalers for delivery of inhaled corticosteroids. Therefore, pressurised metered dose inhalers or the cheapest inhaler device that patients can use adequately should be used as first line treatment.

Table 2.

Results of crossover studies comparing pressurised metered dose inhaler with dry powder inhaler. Negative values or relative risk <1 favours dry powder inhaler

| Outcome | No of studies | No of subjects | Statistic | Treatment effect (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (l) | 5 | 286 | WMD | −0.087 (−0.26 to 0.08) |

| FEV1 | 6 | 342 | SMD | −0.109 (−0.32 to 0.10) |

| Morning peak expiratory flow rate (l/min) | 7 | 392 | WMD | −4.67 (−20.5 to 11.1) |

| Use of additional relief drugs | 2 | 178 | SMD | 0.29 (−0.26 to 0.32) |

| Symptom score: | ||||

| Cough | 2 | 76 | SMD | 0.15 (−0.30 to 0.60) |

| Wheeze | 2 | 76 | SMD | 0.02 (−0.43 to 0.47) |

| Breathlessness | 2 | 76 | SMD | 0.06 (−0.25 to 0.38) |

| Standardised symptom score | 4 | 156 | SMD | −0.06 (−0.25 to 0.38) |

| Exacerbations | 6 | 348 | Relative risk | 1.0 (0.37 to 2.71) |

| Adverse effects: | ||||

| Serum cortisol (mmol/l) | 3 | 118 | WMD | 51.3 (−47.8 to 150.4) |

| Hoarse voice | 5 | 474 | Relative risk | 0.94 (0.61 to 1.45) |

| Oral thrush | 4 | 250 | Relative risk | 1.0 (0.68 to 1.46) |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second, SMD=standardised mean difference, WMD=weighted mean difference.

Figure 3.

Comparison of hydrofluoroalkane versus chlorofluorocarbon pressurised inhalers for delivering beclometasone at 1:1 and 1:2 dose ratios

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a Cochrane review that is available in the Cochrane Library. As with all Cochrane reviews, the authors have committed to keep this review up to date.

The members of the National Health Technology Assessment Inhaler Review Steering Group are Felix Ram (research fellow, Bradford Hospitals NHS Trust), David Brocklebank (specialist registrar in respiratory medicine, Bradford Hospitals NHS Trust), John Wright (consultant in clinical epidemiology and public health, Bradford Hospitals NHS Trust), Chris Cates (general practitioner and Cochrane editor, Bushey, Hertfordshire), John E S White (consultant physician, York Health Services NHS Trust), Martin Muers (consultant physician, United Leeds Teaching Hospitals), Graham Douglas (consultant physician, Aberdeen Royal Hospitals), Linda Davies (senior research fellow, University of York), Dave Smith (research fellow, University of York), and Peter Barry (consultant paediatrician, Leicester Royal Infirmary).

We thank Cochrane Airways Review Group staff at St George's Hospital, London (Steve Milan, Karen Blackhall, Toby Lasserson) for help in identifying trials from the Cochrane Airways register and obtaining copies of papers and Paul Jones for editorial input. We also thank all authors who provided further data for their trials.

Footnotes

Funding: NHS Research and Development Health Technology Assessment Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Review manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration; 2000. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.0. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milanowski J, Qualtrough J, Perrin VL. Inhaled beclomethasone (BDP) with non-chlorofluorocarbon propellant (hydrofluoroalkane 134a) is equivalent to BDP-chlorofluorocarbon for the treatment of asthma. Respir Med. 1999;93:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busse W, Brazinsky S, Jacobson K, Stricker W, Schmitt K, Burgt JV, et al. Efficacy response of inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate in asthma is proportional to dose and is improved by formulation with a new propellant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidgren P, Silvasti M, Poukkula A, Laasonen K, Vidgren M. Easyhaler powder inhaler—a new alternative in the anti-inflammatory treatment of asthma. Acta Therapeutica. 1994;20:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael J, Duncan D, Crompton GK. Beclomethasone dipropionate dry-powder inhalation compared with conventional aerosol in chronic asthma. BMJ. 1978;ii:657–658. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6138.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee SS, Butler AG. Beclomethasone in asthma: a comparison of two methods of administration. Br J Diseases Chest. 1980;74:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(80)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drepaul BA, Payler DK, Qualtrough JE, Perry LJ, Bryony F, Reeve A, et al. Becotide or Becodisks? A controlled study in general practice. Clin Trials J. 1989;26:335–344. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel T, Heinig HJ, Malling B, Scharling, Nikander K, Madsen F. Clinical comparison of inhaled budesonide delivered either via pressurised metered dose inhaler or Turbuhaler. Allergy. 1989;44:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1989.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koskela T, Hedman J, Ekroos H, Kauppinen R, Leinonen M, Silvasti M, et al. Equivalence of two steroid-containing inhalers: Easyhaler multidose powder inhaler compared with conventional aerosol with large volume spacer. Respiration. 2000;67:194–202. doi: 10.1159/000029486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal S, Malhotra SM, Gribben MD, Butler AG. Beclomethasone dipropionate aerosol compared with dry powder in the treatment of asthma. Clin Allergy. 1980;10:259–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1980.tb02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundback B, Alexander M, Day J, Herbert J, Holzer R, Van U, et al. Evaluation of fluticasone propionate (500 μg/day) administered either as a dry powder via a Diskhaler or pressurized inhaler and compared with beclomethasone dipropionate (1000 μg/day) administered by pressurized inhaler. Respir Med. 1993;87:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(05)80264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundback B, Dahl R, De Jonghe M, Hyldebrandt N, Valta R, Payne SL. A comparison of fluticasone propionate when delivered by either the metered-dose inhaler or the Diskhaler inhaler in the treatment of mild-to-moderate asthma. Eur J Clin Res. 1994;5:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieminen MM, Lahdensuo A. Inhalation treatment with budesonide in asthma. A comparison of Turbuhaler and metered dose inhalation with Nebuhaler. Acta Therapeutica. 1995;21(3-4):179–192. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nieminen MM, Vidgren P, Kokkarinen J, Laarsonen K, Liippo K, Lindqvist A, et al. A new beclomethasone dipropionate multidose inhaler in the treatment of bronchial asthma. Respiration. 1998;65:275–281. doi: 10.1159/000029276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poukkula A, Alanko K, Kilpio K, Knuuttila A, Koskinen S, Laitinen J, et al. Comparison of a multidose powder inhaler containing beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) with a BDP metered dose inhaler with spacer in the treatment of asthmatic patients. Clin Drug Invest. 1998;16:101–110. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199816020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toogood JH, White FA, Baskerville JC, Fraher LJ, Jennings B. Comparison of the antiasthmatic, oropharyngeal and systemic glucocorticoid effects of budesonide administered through a pressurized aerosol plus spacer or the Turbuhaler dry powder inhaler. J Allergy Immunol. 1997;99:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahl R, Ringdal N, Ward SM, Stampone P, Donnell D. Equivalence of asthma control with new chlorofluorocarbon-free formulation hydrofluoroalkane-134a beclomethasone dipropionate and chlorofluorocarbon-beclomethasone beclomethasone. Br J Clin Pract. 1997;51:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damedts M, Cohen R, Hawkinson R. Switch to non-chlorofluorocarbon inhaled corticosteroids: a comparative efficacy study of hydrofluoroalkane-BDP and chlorofluorocarbon-BDP metered-dose inhalers. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies RJ, Stampone P, O'Conner BJ. Hydroflouroalkane-134a beclomethasone dipropionate extrafine aerosol provides equivalent asthma control to chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate at approximately half the total daily dose. Respir Med. 1998;92(suppl A):23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross G, Thompson PJ, Chervinsky P, Vanden Burgt J. Hydrofluoroalkane-134a beclomethasone dipropionate, 400 μg, is as effective as chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate, 800 μg, for the treatment of moderate asthma. Chest. 1999;115:343–351. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins M. Clinical evaluation of chlorofluorocarbon-free metered dose inhalers. J Aerosol Med. 1995;8(suppl 1):S41–S47. doi: 10.1089/jam.1995.8.suppl_1.s-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodman K, Bremner P, Burgess C, Crane J, Pearce N, Bearsley R. A comparative study of the efficacy of beclomethasone dipropionate delivered from a breath activated and conventional metered dose inhaler in asthmatic patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 1993;13:61–69. doi: 10.1185/03007999309111534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agertoft L, Pedersen S. Importance of the inhalation device on the effect of budesonide. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:130–133. doi: 10.1136/adc.69.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmunds AT, McKenzie S, Tooley M, Godfrey S. A clinical comparison of beclomethasone dipropionate delivered by pressurised aerosol and as a powder from a Rotahaler. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54:233–235. doi: 10.1136/adc.54.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler LM, Clarke IC PANDA 3 Clinical Study Group. Efficacy and safety of beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) delivered via a novel dry powder inhaler (Clickhaler) in paediatric patients with asthma. Thorax. 1997;52(suppl 6):A57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Walter SD, Griffith LE, Goldstein RS. Interpreting treatment effects in randomised trials. BMJ. 1998;316:690–693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7132.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The use of inhaled corticosteroids in adults with asthma. Drug Ther Bull. 2000;38:5–8. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2000.3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.British Thoracic Society; National Asthma Campaign; Royal College of Physicians. The British guidelines on asthma management: 1995 review and position statement. Thorax. 1997;52(suppl 1):S11. [Google Scholar]