Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study is to examine the prevalence, to report barriers and mental health impact of bullying behaviours and to analyse whether psychological support at work could affect victims of bullying in the healthcare workplace.

Design

Self-administered questionnaire survey.

Setting

20 in total neonatal intensive care units in 17 hospitals in Greece.

Participants

398 healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses).

Main outcome measures

The questionnaire included information on demographic data, Negative Act Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) behaviour scale, data on sources of bullying, perpetrators profile, causal factors, actions taken and reasons for not reporting bullying, psychological support and 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) scores to investigate psychological distress.

Results

Prevalence of bullying measured by the NAQ-R was 53.1% for doctors and 53.6% for nurses. Victims of bullying differed from non-bullied in terms of gender and job experience, among demographic data. Crude NAQ-R score was found higher for female, young and inexperienced employees. Of those respondents who experienced bullying 44.9% self-labelled themselves as victims. Witnessing bullying of others was found 83.2%. Perpetrators were mainly females 45–64 years old, most likely being a supervisor/senior colleague. Common reasons for not reporting bullying was self-dealing and fear of consequences. Bullying was attributed to personality trait and management. Those who were bullied, self-labelled as a victim and witnessed bullying of others had higher GHQ-12 score. Moreover, psychological support at work had a favour effect on victims of bullying.

Conclusions

Prevalence of bullying and witnessing were found extremely high, while half of victims did not consider themselves as sufferers. The mental health impact on victims and witnesses was severe and support at work was necessary to ensure good mental health status among employees.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study globally aiming to investigate workplace bullying in a neonatal intensive care context.

Workplace bullying is one of the main problems medical personnel faces in recent years and studying its prevalence and its impact on behaviours is at the top of the research agenda for many academics and practitioners in healthcare worldwide.

The instrument used in the study does not provide substantial causal evidence or identification of risk factors related to bullying in healthcare employees.

Issues of prevention and mechanisms of controlling and management of bullying were not included in this study and this is a topic for a next research.

Introduction

Workplace bullying has long been recognised as a serious, disruptive problem in modern healthcare organisations.1–4 Bullying aggressive behaviour is defined by criteria as: intention to cause harm or distress, imbalance of power between the bully (perpetrator, aggressor) and the victim (target) and repeatability over time. The majority of definitions, centres on the perception of the victim, but differ in terms of duration, frequency and behavioural acts.2 3 Additionally, bullying is characterised by persistency (in terms of duration and frequency), by the victim’s inability to defend himself/herself and by the negative impact on the victim.3 5–9

Bullying behaviour research is based mainly on two approaches: (1) the self-labelling, by asking the respondents if they perceive themselves as being bullied and (2) the behavioural experience approach, based on valid, well-structured, scientifically sound measure scales. Prevalence rates of workplace bullying depend on the methodology, research design and cultural/geographical characteristics.8 10 Therefore, bullying varies among countries and working sectors; people working in administration and services are bullied more often than those in production, research or education.7 10–13 Nielsen et al in their met analytic study, with the self-labelled method with and without a given definition of bullying found a prevalence of 11.3% and 18.1%, respectively, while the behavioural approach revealed a rate of 14.8%.14

Bullying behaviour is particularly high in healthcare service. Prevalence in the health sector has been reported from 3% to 8% up to approximately 40%, depending on the definition used.3 5 15 Reports from NHS trust showed that a 1/3 among staff,3 44% of nursing staff,16 37% of doctors in training15 had experienced bullying and from USA 84% of medical students suffered from mistreatment during medical school.17 More recently, surveys conducted between 2005 and 2011 for NHS staff showed a prevalence of 15%–18% that rose to 24% in 2012.2

Despite public awareness, government funded research and anti-bullying legislation, bullying still provokes serious problems, sometimes with detrimental effects on both staff’s mental health and quality of healthcare in hospitals. Clinical impact of bullying in hospitals can cause psychosomatic symptoms among healthcare professionals; victims of bullying suffer from anxiety, loss of self-control,17 depression, lower self-confidence,17 occupational job stress, job dissatisfaction,18 dissatisfaction with life,17 burnout syndrome,19 musculoskeletal complaints, increased risk for cardiovascular disease, suicide attempts17 and drug abuse.20 21 Bullying is considered a long-lasting threat for psychological and healthcare problems as longitudinal designed studies have shown.12 20 22

Additionally bullying is associated with increased abseentism,1 23 career damage, poorer job performance, lower productivity resulting in poorer quality of healthcare services and patient care;2 8 in the health sector, bullied doctors make more often medical errors while bullied nurses may have lower levels of commitment and turnover.1 24–26 Bullying and related negative acts are reported in many studies of physicians, nurses, medical personnel and staff working in intensive care units. The challenging environment of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) exposes medical and nursing staff to stress very often on a daily basis. Competition, conflicting demands of professional and personal life,27 excessive workload, difficult working conditions, pressure for prompt diagnosis and difficult decisions about end-of-life care contribute to excessive stress. Bullying adds burden in the NICU’s pressurised and stressful environment and by exposing healthcare staff to more stress increases psychological distress.28 29 It is therefore suggested that stress by creating a vicious cycle with psychological distress promotes victimisation.8 14 As most occupational stress models support, stressors in the work environment generate physical, psychological or behavioural changes for employees.

To our knowledge, there is no research evidence on bullying in the NICU environment except a letter by Patole and Koh.30 31 Given the paucity of research data and the major impact of bullying on staff’s mental health and patient care, the current nationwide survey was conducted for workplace bullying in the Greek NICUs.

The objectives of this study were: (1) to assess the prevalence of workplace bullying in the NICU environment and to examine differences between employees; also to assess witnessing of bullying (2) to investigate sources, characteristics of perpetrators and attitudes towards victims, (3) to examine the impact of bullying on healthcare professional’s mental health and (4) to analyse whether psychological support at work can protect staff from adverse effects of bullying.

Methods

Participants

An anonymous paper questionnaire was sent to physicians and nurses to all 635 healthcare professionals in 20 NICUs at 17 hospitals with a prepaid return envelope. Οther healthcare employees were excluded due to inconsistent presence in NICU’s everyday life. A covering letter explaining the purpose of the study was also included and they received a reminder after approximately 4 weeks. The questionnaire consisted of four sections.

Questionnaire

Section 1 of the questionnaire collected information about the participant’s job professional group, job grade, qualifications/educational level, job contract, job time experience in the field and hours worked/week. Data for gender, age, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, smoking, drinking were also collected.

Section 2 included NAQ-R (Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised) a bullying inventory. NAQ-R was translated from English into Greek language by team researchers and a bilingual English teacher back translated the instrument. The retranslated English version and the original were discussed to confirm agreement in each item for linguistic equivalence.

NAQ-R provides prevalence data for each of the 22 negative behaviours as well as an overall mean score (for an objective approach of bullying). Respondents were asked to rate how often they experienced each negative behaviour from other staff using a five-point frequency scale (1=never, 2=now and then, 3=monthly, 4=weekly, 5=daily). The overall NAQ-R mean score can range from 22 (meaning that the respondent ‘never’ experienced any of the 22 negative behaviours) to a maximum of 110 (meaning that the respondent experienced all of the 22 negative behaviours on a daily basis).32 If ≥3 items were unanswered, then the NAQ score was considered missing.33 A NAQ-R≥33 total score was considered indicative of being a victim of bullying behaviour.32 The internal consistency of NAQ-R as measured by Cronbach’s alpha was found quite satisfactory at 0.95.

Additionally, for a subjective approach, NAQ-R includes a self labelled definition of bullying (stem question). The definition used was: ‘bullying is a situation where one or several individuals persistently over a period of time perceive themselves as being the receivers of a series of negative actions, from one or more several persons, in a situation where the target of bullying has difficulty in defending him or herself against these actions. We will not refer as one-off incident as bullying’. Respondents were asked to respond on a five-point scale (1=no, 2=yes, but only rarely, 3=yes, now and then, 4=yes, several times per week, 5=yes, almost daily). NAQ-R also examines whether respondents experienced bullying behaviours from peers, senior staff or managers in the past 6 months.34

Section 3 collected data on perpetrators’ profile (age, gender and professional status), causality, actions taken (whether they reported bullying behaviour to any authority) and reasons that bullying was not reported.

In section 4, data were reported on mental health impact using General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and psychological support at work. The 12-item GHQ (GHQ-12), an efficient, reliable and well-validated indexed scale, was used to assess psychological distress.35 36 GHQ data are scored as a 4-Likert scale (from 0 to 3), to measure severity. Results were evaluated at the more conservative cut-off of ≥4 used in healthcare research for psychological impairment.29 The scale had a satisfactory internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90. Support at work was measured as a dichotomous scale with a yes/no response if the respondents received psychological support or not.

Statistical analysis

Frequency analysis for sociodemographic characteristics and item analysis were used to know the internal consistency of NAQ-R and GHQ-12 by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient; exploratory analysis (principal component analysis) was carried out to identify factor structure of NAQ-R and GHQ-12. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables for differences between group frequencies. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the association between GHQ-12 scores and NAQ-R total score. To test for moderators, buffering the individual against bullying, we used univariate analysis of variance with the dependent being mental health impact.

Through this paper, data were based on valid responses for each group or subgroup, since not all respondents answered all questions. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS V.17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

This study is inclusive in nature and provides ground for generalisation since it was carried out in 17 hospitals across country. The total sample was 635 employees (doctors, n=232; nurses, n=403) working in 20 NICUs nationwide. Three hundred and ninety-eight employees responded to the questionnaire (overall response rate 62.8%). The response rate among the NICUs ranged from 18% to 100%.

Characteristics of the victims of bullying

The mean (SD) age was 43.3 (9.5) years, 163 (41%) were physicians and 235 (59%) nurses. The mean (SD) working hours/week were 47.9 (13.2) and most of the respondents had a permanent job contract (72%). Smoking was assessed by means of a question about whether the respondent was a current smoker (n=88.22%) or non-smoker (n=312.78%). Two hundred and eighty-three (72.9%) of the respondents referred to a non-sedentary lifestyle, indicated by physical activity and only 11 (2.8%) of them to alcohol consumption.

Professional groups of doctors and nurses by demographic data (gender, age, job contract, hours worked/week), health risk behaviour (BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption) are presented in table 1. Professional job grade for doctors and nurses, educational level and job experience in the field are presented in table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants and exposure to bullying*

| n (%) | Bullied, n (%) | Not bullied, n (%) | P value | |

| Occupational group (n=398) | ||||

| Neonatologists | 160 (40.7) | 85 (53.1) | 75 (46.9) | NS |

| Nurses | 233 (59.3) | 125 (53.6) | 108 (46.4) | |

| Gender (n=401) | ||||

| Male | 50 (12.6) | 18 (36) | 32 (64) | 0.009 |

| Female | 346 (87.4) | 195 (56.4) | 151 (43.6) | |

| Age (n=366) | ||||

| 26–35 | 64 (17.6) | 40 (62.5) | 24 (37.5) | NS |

| 36–45 | 162 (44.5) | 86 (53.1) | 76 (46.9) | |

| 46–55 | 113 (31) | 55 (48.7) | 58 (51.3) | |

| 56+ | 25 (6.9) | 12(48) | 13(52) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n=383) | ||||

| Up to 18.5 | 13 (3.4) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | NS |

| 18.5–24.9 | 239 (63.2) | 132 (55.2) | 107 (44.8) | |

| 25–29.9 | 92 (24.4) | 45 (48.9) | 47 (51.1) | |

| >30 | 34 (9) | 17(50) | 17(50) | |

| Physical activity (n=388) | ||||

| Yes (non-sedentary) | 281 (73.2) | 152 (54.1) | 129 (45.9) | NS |

| No (sedentary) | 103 (26.8) | 54 (52.4) | 49 (47.6) | |

| Smoker (n=400) | ||||

| Yes (smoker) | 87 (22) | 45 (51.7) | 42 (48.3) | NS |

| No (non-smoker) | 308 (78) | 167 (54.2) | 141 (45.8) | |

| Alcohol (n=395) | ||||

| Yes (high-low) | 11 (2.8) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | NS |

| No (no) | 380 (97.2) | 203 (53.4) | 177 (46.6) | |

| Job contract (n=368) | ||||

| Permanent | 262 (72) | 140 (53.4) | 122 (46.6) | NS |

| Not permanent | 94 (25.8) | 47(50) | 47(50) | |

| Other | 8 (2.2) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Hours of work (n=374) | ||||

| Up to 40 | 242 (65.6) | 128 (52.9) | 114 (47.1) | NS |

| >40 | 127 (34.4) | 73 (57.5) | 54 (42.5) | |

*Multiple responses could not be entered. Not all respondents answered all questions of NAQ score.

BMI, body mass index; NAQ, Negative Acts Questionnaire; NS, not significant.

Table 2.

Study participants and exposure to bullying*

| n (%) | Bullied, n (%) | Not bullied, n (%) | P value | |

| Doctors (n=164) | ||||

| Registrar | 36 (22.4) | 22 (61.1) | 14 (38.9) | NS |

| Senior Registrar | 42 (26.1) | 19 (45.2) | 23 (54.8) | |

| Consultant | 71 (44) | 40 (56.3) | 31 (43.7) | |

| Research Assistant/Fellow | 12 (7.5) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Nurses (n=235) | ||||

| Nurse | 126 (54) | 67 (53.2) | 59 (46.4) | NS |

| Midwife | 82 (35.2) | 46 (56.1) | 36 (43.9) | |

| Lead Nurse | 14 (6) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) | |

| Head Nurse | 11 (4.8) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Educational level (n=393) | ||||

| Technological Educational Institute | 185 (47.7) | 94 (50.8) | 91 (49.2) | NS |

| University | 95 (24.5) | 56 (58.9) | 39 (41.1) | |

| Postgraduate | 108 (27.8) | 59 (54.6) | 49 (45.4) | |

| Job experience in the field (n=342) | ||||

| <5 years | 78 (23.1) | 44 (56.4) | 34 (43.6) | 0.048 |

| 5–10 years | 55 (16.3) | 35 (63.6) | 20 (36.4) | |

| 10.1–20 years | 116 (34.3) | 65(56) | 51(44) | |

| >20 years | 89 (26.3) | 37 (41.6) | 52 (58.4) | |

*Multiple responses could not be entered. Not all respondents answered all questions.

NS, not significant.

According to data analysis, 213 employees (53.5%) were estimated as being bullied based on NAQ-R score (≥33). Demographic data (age, job contract, hours at work/week), health risk behaviour (BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol), job grade and educational level did not differ significantly among bullied and non-bullied employees. Victims of bullying differed from non-bullied in terms of gender and job experience in the NICU working environment (tables 1 and 2).

Prevalence of bullying and witnessed bullying

Based on NAQ-R score the prevalence of bullying was estimated at 53.5% (213/398 respondents) with doctors at 53.1% (85/160) and nurses at 53.6% (125/233), respectively.

Self-labelling as a victim of bulling was present for 108/387 respondents (27.9%) while 279/387 (72.1%) did not refer being bullied. Bullying was referred as mainly occasional, with 92.8% of the bullied staff experiencing at least one negative behaviour over the last 6 months, leaving 7, and 2% on a daily or weekly basis.

Doctors self-labelled as victims more commonly than nurses (n=53/156, 34% vs n=52/226, 23%, X2(1)=5.56, P=0.02). Additionally, only 92/205 of those who experienced bullying (NAQ≥33), self-labelled themselves as victims (sensitivity 44.9%), leaving 113/205 (55.1%) not labelling themselves as victims. On the other hand, 166/182 of those who did not experience bullying (NAQ<33) did not self-label themselves as victims (specificity 91.2%).

Three hundred and twenty-seven (n=325/390, 83.3%) employees witnessed bullying of others in the previous 6 months. Doctors witnessed others being bullied (n=137/161, 85.1%), similar to nurses (n=188/229, 82.1%) (X2(1)=0.611, P, NS).

Prevalence of negative behaviours

The vast majority (92.8%) had experienced at least one negative behaviour occasionally over the last 6 months and 37.2% experienced at least one negative behaviour on a daily or weekly basis. Two-thirds (76.1%) had experienced five or more negative behaviours to some degree over the last 6 months and 8.5% had experienced five or more negative behaviours on a daily or weekly basis.

Differences on the overall NAQ-R mean score were estimated using t-test statistical analysis.

Female employees had a NAQ score 37.07±12.55 significantly higher than men 31.44±10.45 (P<0.003). Job experience was inversely related to bullying, meaning that the lesser time in the job led to more severe behaviour. Employees with experience time <5 years had higher NAQ score than employees of 20+ years (37.67±14.2 vs 32.90±9.48 (P<0.015)).

Finally, overall NAQ score showed a gradual decrease by age from 39.98±12.68 at the age of 26–35 years to 33.6±11.08 at the age of 56+.

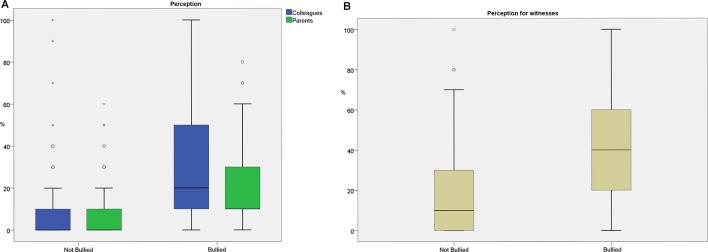

Perception of bullying

Employee’s perception of bullying by colleagues and parents and those who witnessed bullying of others differed significantly between bullied and non-bullied professional staff (figure 1). Bullied respondents perceived themselves as victims of bullying by colleagues and parents at a mean (SD) at 30 (6.9) % and 17.8 (18) % significantly higher than non-bullied at 9.44 (15.2) % and 8 (11.4) %, respectively (P<0.001) (figure 1A). Bullied respondents who witnessed bullying of others perceived bullying at a mean (SD) 39.67 (26.5) % significantly higher than non-bullied respondents who witnessed bulling of others at 17.9 (19.5) % (P<0.001) (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Perception of bullying by colleagues and parents between bullied and non-bullied respondents. (B) Perception being a witness of bullying of others between bullied and non-bullied respondents

Reporting of bullying, characteristics of the perpetrator and causes of bullying

Data analysis shows that 58.1% of respondents being bullied. Of those who complained, most frequent actions taken to deal with were personal reprove (49.1%), management/labour union involvement (19.3%) and legislation (10.5%). Reasons for not reporting bullying were personal self-dealing (67.2%), fear of consequences (19%) and ignoring as a non-important problem (6.9%). Additionally, 69.4% (59/85) of respondents referred being bullied in presence of others, 12.9% (11/85) alone and 17.6% (15/85) at both conditions.

The respondents reported that when an incident occurred, the perpetrator was most likely to be a supervisor/senior colleague (40.7% of those bullied, n=37), followed by peers (26.4% of those bullied, n=24), a manager (22% of those bullied, n=22) and parents (7.7%, n=7). In 10.5% of those bullied, the victim was being bullied by a male person (n=10/95), in 37.9% by a female (n=49/95) and in 51.6% by both (n=36/95). In 60.8%, the perpetrator was a male of age 45–64 years old, otherwise female of 45 to 54 years old in 63.5%. It was more than one person behaving disrespectfully for male perpetrators in 46.7% (14/30) while for female perpetrators 55% (33/60).

Regarding causes of bullying, personality trait (50.5%), management (32.2%) and workplace culture (10.7%) were highlighted as the most important.

Mental health impact of bullying

Bullying exposure, witnessed bullying of others and self-labelling as a victim were associated with lower levels of psychological health status. GHQ-12 score was found higher for employees being bullied versus those who were non-bullied (12.9±5.7 vs 8.5±4.6, respectively, P<0.001), for witnesses bullying versus those who did not witness bullying of others (11.5±5.5 vs 7.5±5.7, respectively, P<0.001) and for those who self-labelled as victims versus those who did not self-label as victims (13.9±6.32 vs 4.98±9.73 respectively, P<0.001). Additionally, for those who self-labelled as victims, the more often it was reported (daily 22.6±7.82 vs rarely 13.01 ±6.19, P<0.001), the higher the GHQ-12 score was.

GHQ-12 score was found higher for doctors compared with nurses (11.58±5.59 vs 10.32±5.76, P<0.038) and for women healthcare providers compared with men (11.13±5.7 vs 9.23±5.62, P<0.033). GHQ-12 was not associated with any of all other characteristics (job grade, educational level, job contract, hours worked/week, age, BMI, alcohol consumption and smoking).

The overall correlation between NAQ score and GHQ-12 score was found satisfactory (r2=0.385, P<0.001). The recommended cut-off score of ≥4 indicative of severe psychological distress, ranged from 24.2% (37/153) for doctors to 22.7% (46/212) for nurses.

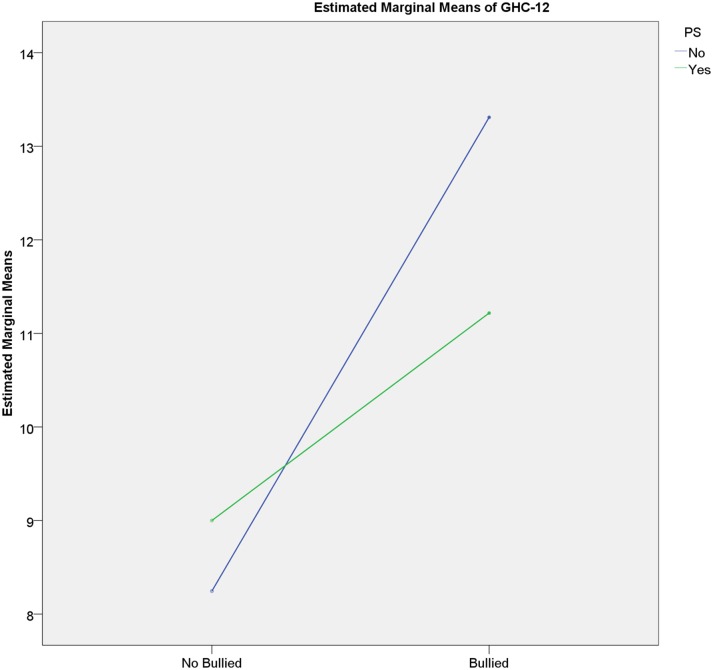

Bullying and psychological support

The moderator effect that psychological support had on GHQ-12 scale for those employees being bullied or not is shown as an interaction in figure 2. Bullied staff with psychological support had a GHQ-12 of 11.22±6.34 (while those who were not on psychological support 13.31±5.4), that was higher compared with non-bullied employees either they were on psychological support at 9±3.53 or not 8.25±5.11.

Figure 2.

Psychological support as a buffer against bullying.

Conclusion

The main purpose of the current study was to assess prevalence, to examine differences between bullied and non-bullied healthcare staff, to investigate sources, characteristics of perpetrators and barriers to reporting bullying and finally, to examine the impact on mental health status and the role of psychological support at work. The response rate in the current survey was quite satisfactory. The high response rate reflects the healthcare providers’ interest in this topic, since it is the first nationwide survey for bullying in NICUs.

Healthcare professions have one of the highest levels of bullying in the workplace.37 Prevalence rate of bullying in the current study was found high for doctors and nurses as other studies have shown.5 8 16 It seems that the highly stressful NICU environment can foster negative behaviours. Interpersonal relations among professional staff members, administrative problems, understaffing, overwork and productivity expectations promote disruptive and corrosive behaviours such as bullying. In our study, with the self-labelling definition bullying referred at one-third of respondents. On the other hand, half of bullied respondents did not self-label themselves as victims, possibly due to non-recognition or not-knowing or no-realisation of this behaviour.28 As studies have shown if the prevalence of bullying is based on a given definition, many victims are either unaware or do not admit being bullied or decline the victim role as it suggests weakness and passivity.38 39 The rate of witnessing bullying of others was found much higher than Quine and Carter studies, possibly due to the fact that experiencing bullying is easier to refer than to admit.2 3 15

Demographic group differences for victims of bullying were found only for gender and job experience in the field. Higher bullying prevalence among women compared with men, as this study shows, has been referred by many studies, while others did not report any differences.7 40–42

This lack of consistency could be attributed to discriminations that both genders can suffer or to the broader dysfunctional practices (involving sexual harassment) that bullying actions incorporate.

Regarding organisational factors, we did not find any differences related to job contract, job position and professional group, supportive to Kivimäki et al1 findings. The fact that bullying prevalence did not differ for doctors and nurses, job position and educational level at both professional groups, does not support a pattern of discrimination as other studies have shown.15 17 Workplace bullying is a widespread complex phenomenon, both in interpersonal and organisational level, not involving certain professional groups.1 Crude NAQ-R score was found to be significantly higher according to gender (higher for women), age (higher for younger employees), job experience in the field (higher for less years of experience) and witnessing bullying of others. This finding supports Rayner et al and Hoel et al studies who noted that younger employees being in a subordinate position are more frequently exposed to bullying behaviour.42 43 On the contrary, Einarsen and Skogstad found the exactly opposite results with seniors being bullied more often than younger employees.44

Bullying in the health sector includes specific interactions among supervisors, healthcare staff, coworkers and visitors (parents/families) in the NICU environment. Bullying from colleagues and parents was perceived easier by bullied employee’s (recipients) and those who witnessed bullying of others (observers), indicative of a more susceptible approach by them.45 Seniors/supervisors, other than colleagues and parents were reported as the most common sources of bullying.17 Many other studies have shown that bullying is a top-down process with most of the perpetrators being in a superior status supportive of imbalance of power.17 43 Also, the fact that bullying behaviour occurs between peers in team working environments (as NICU) is in line with Zapf et al study.46 Although male-dominated organisations are associated with high rates of bullying, our study showed that it also exists in a highly female-dominated environment.5 The fact that perpetrators female and male were mainly 45–64 years old signals the need for intervention policies. Furthermore, our study showed that half of male or female perpetrators were more than one person. Nearly 70% of respondents referred being bullied in presence of others suggesting that bullying takes place both on an individual and social-group level.12 Under-reporting bullying associates to understanding the barriers that healthcare professionals arise to report bullying. Reasons for not reporting were mainly personal self-dealing and fear for consequences. The last could be attributed to the belief that bullying may have an impact on their professional progress.47 Anti-bullying policies should decrease barriers to reporting bullying and increase staff confidence in preventing and dealing with this behaviour. Our study stresses out that personality trait of victims, management and workplace culture were considered as the main causes of bullying. Personality trait characterises people who can be ‘easy to target’ persons, supporting the widespread concept of ‘blaming the victim’.8 48

In our study, respondents being bullied, those self-labelling themselves as victims and witnessed bullying of others, had higher GHQ-12 scores indicative of psychological stress. Doctors among other healthcare workers are at increased risk for occupational stress.49 In our study, either they had been bullied or not, doctors had higher levels of psychological distress than nurses and females than males. The high GHQ-12 score among doctors reflects the effect of pressurised working conditions, heavy workload and daily crucial decisions about life and death. Weinberg and Creed’s study showed that stressful conditions at work contribute to psychological distress, as a result of the vicious cycle that heavy workload creates with anxiety and depression.27 29 Moreover, a quarter of doctors and nurses reported high GHQ-12 scores indicative of severe psychological distress as other studies have noted.50 GHQ-12 showed no differences regarding other characteristics (job grade, educational level, job contract, job experience in the field, hours worked/week, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption) as noted in other studies.49 51 Correlation of bullying with mental health status, as high NAQ scores were accompanied by high GHQ-12 scores, shows bullying association with psychological distress. Einarsen et al portray victims of bullying, as persons with low self-confidence, being depressed, anxious, suspicious, uncertain and disappointed.28 In our study, the psychological component of bullying was surfaced. Those who had been bullied and were on psychological support had better mental health status (lower GHQ-12 score) than those who had been bullied and were not on psychological support. On the other hand, the non-bullied and psychologically supported compared with non-bullied and not psychologically supported respondents had worse mental health status (higher GHQ-12 score). As other studies have shown, an association between mental health status bullying and psychological support exist, with the last considered as a buffer against bullying.5 8 Moreover, a supportive work environment and factors such as job control and personal self-regulation can play a protective role (act as buffers) against bullying negative acts.3 52 53 The authors strongly believe that changes in the work design (emphasis on teamwork, delegation and autonomy) and implementation of organisation-wide HR initiatives such as awareness building, education and counselling can provide psychological assistance and act as barriers to bullying in the NICU environment.54 55 Although the study was systematically organised, objectives were met and findings provided a ground for generalisation (especially in a neonatal context), there are several limitations. First, the questionnaire used in the study does not provide substantial causal evidence (or identification of risk factors) that bullying has on healthcare employees. Furthermore, issues of prevention and mechanisms of controlling and management of bullying in a neonatal context were not included in the questionnaire. Finally, respondent’s perceptions subjectivity to the topic should be examined in further research.

The disturbing extremely high rates of bullying, along with the higher levels of psychological stress for those being bullied, reveal the negative effects of bullying on both professional groups of doctors and nurses. A supportive work environment protects staff and moderates any harmful effects from bullying behaviour. Management of bullying must be based on freely reporting bullying behaviours and staff should not be reluctant to report bullying. First priority for doctors and nurses working in the NICU should be team work and cooperation. More studies for disruptive behaviours such as bullying are needed, considering the demanding NICU environment, the pressured working conditions, the existing heavy workload and conflicts among staff.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank:

Athena Nona-Georgiou Teacher of English-Translator for contributing to back to back translation of NAQ-R and GHQ-12 score, Helen Tsirkou to English language formation, Kostas Tzanas for statistical advice and the NICUs staff for participating in this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: IC planned the study, analysed the results and drafted the paper; he is also the guarantor. FGB and PC planned the study, managed the survey and collected the results. FV commented on the plans and helped with the final draft. GM commented on the plans.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The research was approved by participating Hospital’s Scientific Committee’s for Medical Research Ethics.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are published as part of this study.

References

- 1.Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Workplace bullying and sickness absence in hospital staff. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:656–60. 10.1136/oem.57.10.656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter M, Thompson N, Crampton P, et al. Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: a questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002628 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quine L. Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: staff questionnaire survey. BMJ 1999;318:228–32. 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray JS. Workplace bullying in nursing: a problem that can’t be ignored. Medsurg Nurs 2009;18:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quine L. Workplace bullying in nurses. J Health Psychol 2001;6:73–84. 10.1177/135910530100600106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockhart K. Experience from a staff support service. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 1997;7:193–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vartia M. The sources of bullying–psychological work environment and organizational climate. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 1996;5:203–14. 10.1080/13594329608414855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ariza-Montes A, Muniz NM, Montero-Simó MJ, et al. Workplace bullying among healthcare workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:3121–39. 10.3390/ijerph10083121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van de Vliert E, Einarsen S, Nielsen MB. Are national levels of employee harassment cultural covariations of climato-economic conditions? Work Stress 2013;27:106–22. 10.1080/02678373.2013.760901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Power JL, Brotheridge CM, Blenkinsopp J, et al. Acceptability of workplace bullying: a comparative study on six continents. J Bus Res 2013;66:374–80. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.08.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen MB, Skogstad A, Matthiesen SB, et al. Prevalence of workplace bullying in Norway: Comparisons across time and estimation methods. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2009;18:81–101. 10.1080/13594320801969707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen MB, Hetland J, Matthiesen SB, et al. Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying and psychological distress. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012;38:38–46. 10.5271/sjweh.3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giorgi G, Arenas A, Leon-Perez JM. An operative measure of workplace bullying: the negative acts questionnaire across Italian companies. Ind Health 2011;49:686–95. 10.2486/indhealth.MS1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen MB, Matthiesen SB, Einarsen S. The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying. A meta-analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol 2010;83:955–79. 10.1348/096317909X481256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quine L. Workplace bullying in junior doctors: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2002;324:878–9. 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellasega CA. Bullying among nurses. Am J Nurs 2009;109:52–8. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000344039.11651.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ 2006;333:682 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno Jiménez B, Rodríguez Muñioz A, Martínez Gamarra M, et al. Assessing workplace bullying: Spanish validation of a reduced version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire. Span J Psychol 2007;10:449–57. 10.1017/S1138741600006715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Job Satisfaction and burnout among intensive care unit nurses and physicians. Crit Care Res Pract 2013;2013:1–6. 10.1155/2013/786176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einarsen S, Nielsen MB. Workplace bullying as an antecedent of mental health problems: a five-year prospective and representative study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:131–42. 10.1007/s00420-014-0944-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vartia MA. Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scand J Work Environ Health 2001;27:63–9. 10.5271/sjweh.588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML. Workplace bullying and mental health: a meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135225 10.1371/journal.pone.0135225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortega A, Christensen KB, Hogh A, et al. One-year prospective study on the effect of workplace bullying on long-term sickness absence. J Nurs Manag 2011;19:752–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paice E, Smith D. Bullying of trainee doctors is a patient safety issue. Clin Teach 2009;6:13–17. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2008.00251.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berthelsen M, Skogstad A, Lau B, et al. Do they stay or do they go? Int J Manpow 2011;32:178–93. 10.1108/01437721111130198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogh A, Hoel H, Carneiro IG. Bullying and employee turnover among healthcare workers: a three-wave prospective study. J Nurs Manag 2011;19:742–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oates RK, Oates P. Stress and mental health in neonatal intensive care units. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1995;72:F107–10. 10.1136/fn.72.2.F107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Einarsen S. The nature, causes and consequences of bullying at work: The Norwegian experience. Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé 2005. 10.4000/pistes.3156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg A, Creed F. Stress and psychiatric disorder in healthcare professionals and hospital staff. Lancet 2000;355:533–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07366-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patole S. Bullying in neonatal intensive care units: free for all. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2002;86:68F–68. 10.1136/fn.86.1.F68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koh TS, Koh TH. Bullying in hospitals. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:610–10. 10.1136/oem.58.9.610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Notelaers G, Einarsen S. The world turns at 33 and 45: defining simple cutoff scores for the negative acts questionnaire–revised in a representative sample. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2013;22:670–82. 10.1080/1359432X.2012.690558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksen GS, Nygreen I, Rudmin FW. Bullying among hospital staff: use of psychometric triage to identify intervention priorities. J Appl Psychol 2011;7:26–31. 10.7790/ejap.v7i2.252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Einarsen S, Hoel H, Notelaers G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work Stress 2009;23:24–44. 10.1080/02678370902815673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werneke U, Goldberg DP, Yalcin I, et al. The stability of the factor structure of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 2000;30:823–9. 10.1017/S0033291799002287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesage F-X, Martens-Resende S, Deschamps F, et al. Validation of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) adapted to a work-related context. Open J Prev Med 2011;1:44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zapf D, Einarsen S. Individual antecedents of bullying: Victims and perpetrators : Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper C, Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice. Boca Raton, FLl: CRC Press, 2011:177–200. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikkelsen EG, Einarsen S. Bullying in Danish work-life: Prevalence and health correlates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2001;10:393–413. 10.1080/13594320143000816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Einarsen S. Harassment and bullying at work. Aggress Violent Behav 2000;5:379–401. 10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00043-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salin D. Ways of explaining workplace bullying: a review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Human Relations 2003;56:1213–32. 10.1177/00187267035610003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams JH, et al. Incivility in the workplace: incidence and impact. J Occup Health Psychol 2001;6:64–80. 10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rayner C. The incidence of workplace bullying. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 1997;7:199–208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoel H, Cooper CL, Faragher B. The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2001;10:443–65. 10.1080/13594320143000780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Einarsen S, Skogstad A. Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 1996;5:185–201. 10.1080/13594329608414854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Einarsen S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. Int J Manpow 1999;20:16–27. 10.1108/01437729910268588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zapf D. Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. Int J Manpow 1999;20:70–85. 10.1108/01437729910268669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pisklakov S, Tilak V, Patel A, et al. Bullying and Aggressive Behavior among Health Care Providers: Literature Review. Advances in Anthropology 2013;3:179–82. 10.4236/aa.2013.34024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finne LB, Knardahl S, Lau B. Workplace bullying and mental distress - a prospective study of Norwegian employees. Scand J Work Environ Health 2011;37:276–86. 10.5271/sjweh.3156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coomber S, Todd C, Park G, et al. Stress in UK intensive care unit doctors. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:873–81. 10.1093/bja/aef273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 1996;347:724–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90077-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Firth-Cozens J, Moss F. Hours, sleep, teamwork, and stress. Sleep and teamwork matter as much as hours in reducing doctors' stress. BMJ 1998;317:1335–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hauge LJ, Skogstad A, Einarsen S. The relative impact of workplace bullying as a social stressor at work. Scand J Psychol 2010;51:426–33. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson LM, Demaray MK. Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. Sch Psychol Rev 2007;36:383–405. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baillien E, De Witte H. The Relationship Between the Occurrence of Conflicts in the Work Unit, the Conflict Management Styles in the Work Unit and Workplace Bullying. Psychol Belg 2009;49:207–26. 10.5334/pb-49-4-207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woodrow C, Guest DE. When good HR gets bad results: exploring the challenge of HR implementation in the case of workplace bullying. Hum Resour Manage 2014;24:38–56. 10.1111/1748-8583.12021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.