Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of melanoma is increasing faster than any other major cancer both in Brazil and worldwide. The Southeast of Brazil has especially high incidences of melanoma, and early detection is low. Exposure to UV radiation represents a primary risk factor for developing melanoma. Increasing attractiveness is a major motivation for adolescents for tanning. A medical student-delivered intervention that harnesses the broad availability of mobile phones as well as adolescents’ interest in their appearance may represent a novel method to improve skin cancer prevention.

Methods and analysis

We developed a free mobile app (Sunface), which will be implemented in at least 30 secondary school classes, each with 21 students (at least 30 classes with 21 students for control) in February 2018 in Southeast Brazil via a novel method called mirroring. In a 45 min classroom seminar, the students’ altered three-dimensional selfies on tablets are ‘mirrored’ via a projector in front of their entire class, showing the effects of unprotected UV exposure on their future faces. External block randomisation via computer is performed on the class level with a 1:1 allocation. Sociodemographic data, as well as skin type, ancestry, UV protection behaviour and its predictors are measured via a paper–pencil questionnaire before as well as at 3 and 6 months postintervention. The primary end point is the group difference in the 30-day prevalence of daily sunscreen use at a 6-month follow-up. Secondary end points include (1) the difference in daily sunscreen use at a 3-month follow-up, (2) if a self-skin examination in accordance with the ABCDE rule was performed within the 6-month follow-up and (3) the number of tanning sessions.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Itauna. Results will be disseminated at conferences and in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

NCT03178240; Pre-results.

Keywords: dermatology, preventive medicine, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study measuring the longitudinal effectiveness of a photoageing mobile app to change sun protection behaviour.

External randomisation via computer and a relatively high number of clusters ensure good comparability between groups.

Cluster effects cannot be excluded because the intervention and control classes are located in the same schools.

Introduction

According to the WHO, the incidence of melanoma is increasing more rapidly than any other major cancer both in Brazil and worldwide. Melanoma is one of the most common cancers in young adults and poses substantial health and economic burdens.1

Approximately 90% of melanomas are associated with UV exposure, in particular with the frequency of severe sunburns, and are therefore highly preventable.2 Multiple studies showed that daily sunscreen use with a sun protection factor (SPF) above 30, as recommended by international dermatology guidelines, may prevent sunburns and skin cancer including melanoma.3–6

Brazil has one of the highest UV indexes on earth; additionally, tanning is culturally established and Brazilians commonly experience unprotected overexposure to the sun, especially in their childhood and teenage years.7–11 In a 2008 population-based survey with 1604 participants in the south of Brazil, 48.7% reported at least one sunburn in the prior year10 In an attempt to mitigate the health damage caused by excessive UV exposure, Brazil was the first country to prohibit indoor tanning in 2009, although with limited success.9 The Southeast of Brazil (the location of this study) is especially populated by citizens with a European ancestry and therefore has high incidences of melanoma (up to 23.5/100 000 inhabitants) with a lack of early diagnosis and an overall survival below worldwide rates.12–15

Interventions encouraging sun protection habits are important, particularly among adolescents, as increased risk of skin cancer is associated with cumulative UV exposure and sunburns early in life.16–18 In line with this association, various recent experimental studies to test these effects in young target groups aimed at promoting sunscreen use as an end point,19–22 and others used various UV protection behaviours (including avoiding sunbeds) or behavioural scores.23–32 Given the substantial amount of time that children and adolescents spend in the school environment, addressing skin cancer prevention in this setting is crucial and provides a unique opportunity to propel skin cancer prevention programmes.33

Despite the effectiveness of daily sunscreen and its implementation in international dermatological guidelines,34 a study conducted in Brazil among 398 medical students from the city of Curitiba showed that only 8.4% use sunscreen daily, 4.3% had already used tanning beds and 85.5% had past sunburns despite having undergone a clinical rotation in a Dermatology department.8 The lack of exemplary behaviour among prospective physicians regarding skin cancer prevention is known on a global scale.35–37 The authors of this study have concluded that novel engagement methods are needed to answer the increasing demand for skin cancer awareness among physicians.

The Sunface mirroring intervention aims to provide science-based skin cancer prevention to a large number of adolescents and to sensitise prospective physicians to the importance of exemplary behaviour.38–40

Current knowledge on school-based skin cancer prevention

Unhealthy behaviour with respect to UV exposure is mostly initiated in early adolescence,41 commonly with the belief that a tan increases attractiveness42–44 and the problems related to melanoma as well as skin atrophy are too far in the future to fathom.

A recent randomised trial with Australian high school students demonstrated that appearance-based videos on UV-induced premature ageing were superior in encouraging sunscreen use to videos of the same length focusing exclusively on health aspects.19 These findings are in line with international studies demonstrating the important influence of self-perceived attractiveness on self-esteem in adolescence.45 46 Furthermore, enhancing one’s attractiveness is a primary motivation for tanning in adolescents both in Brazil and worldwide.42 47 48 In addition, the success of appearance-based photoageing intervention mobile apps, in which an image is altered to predict future appearance in the fields of tobacco and adiposity prevention, shows promise for these interventions in behavioural change settings. 49–56

In the setting of skin cancer prevention, a quasi-experimental study by Williams et al57 demonstrated significantly higher scores for predictors of sun protection behaviour in young women from the UK (70 participants in total) using a photoageing desktop programme. Furthermore, the photoageing software ‘showed promising reduction in young adults’ tanning intentions in a study with 10 participants in total (7 women and 3 men).58 However, prior studies are limited by their small sample size and limitations related to expanding the target population.

Introduction of the Sunface app

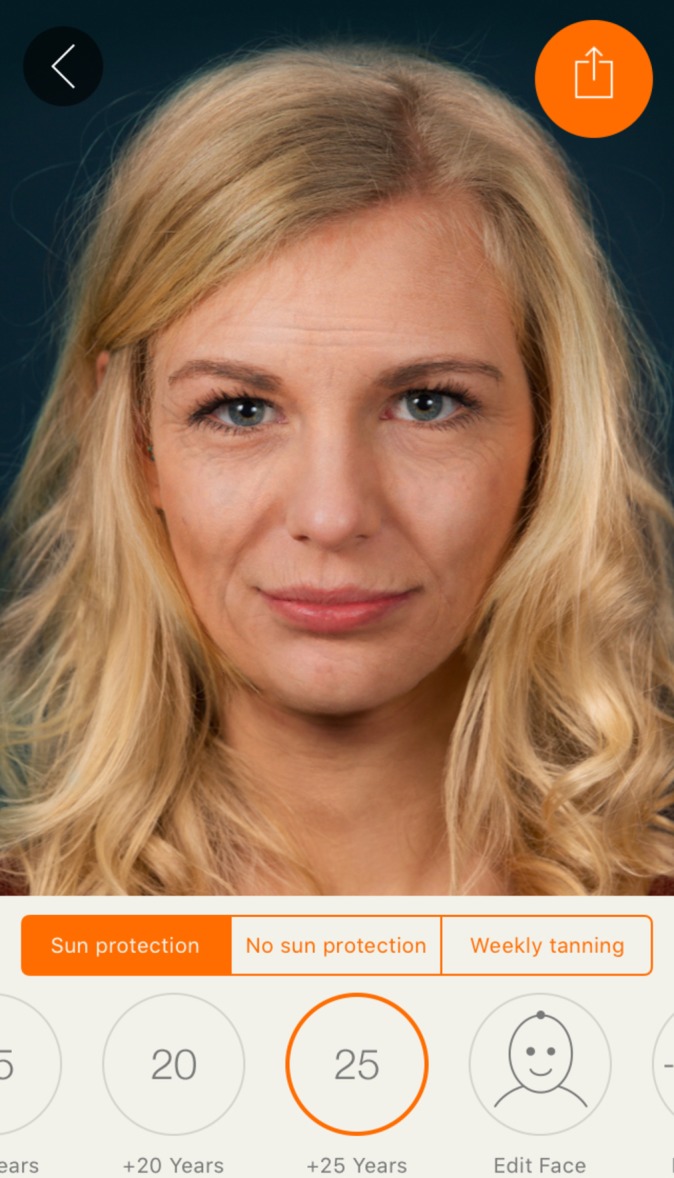

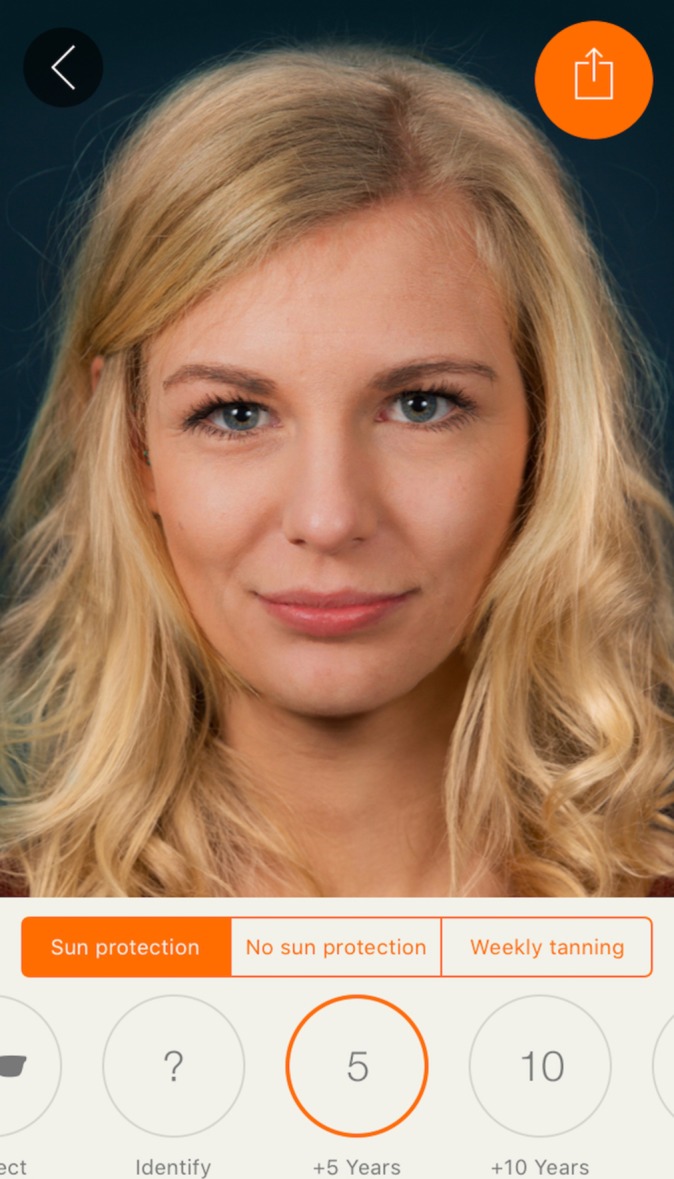

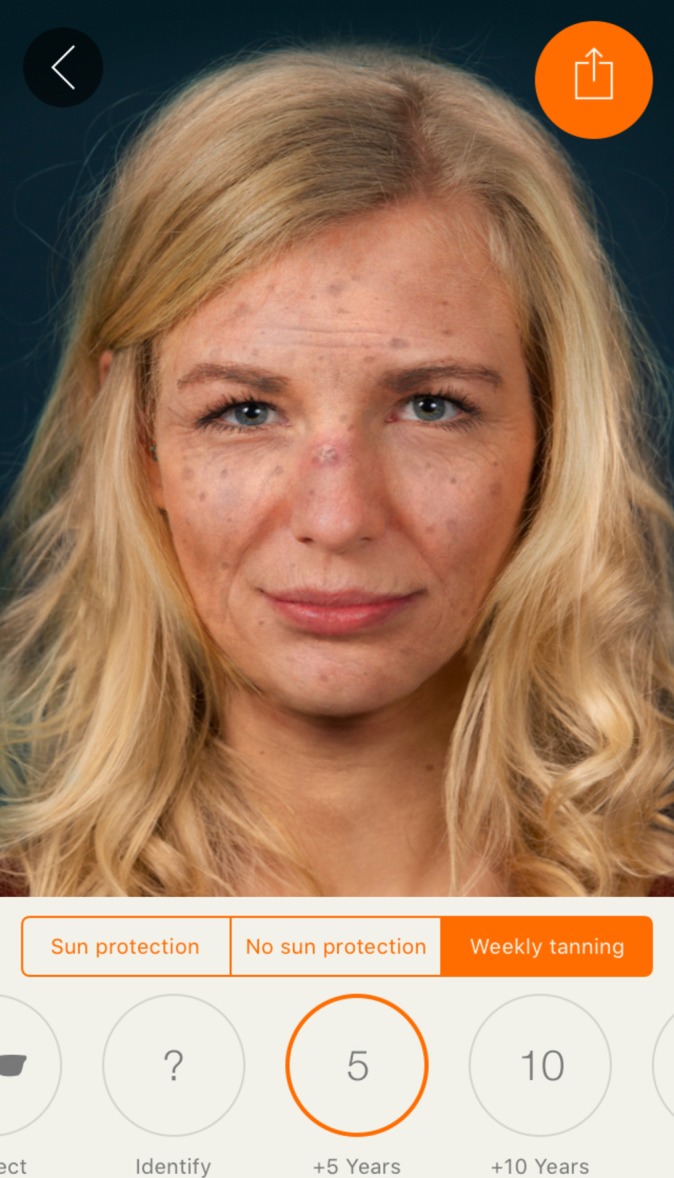

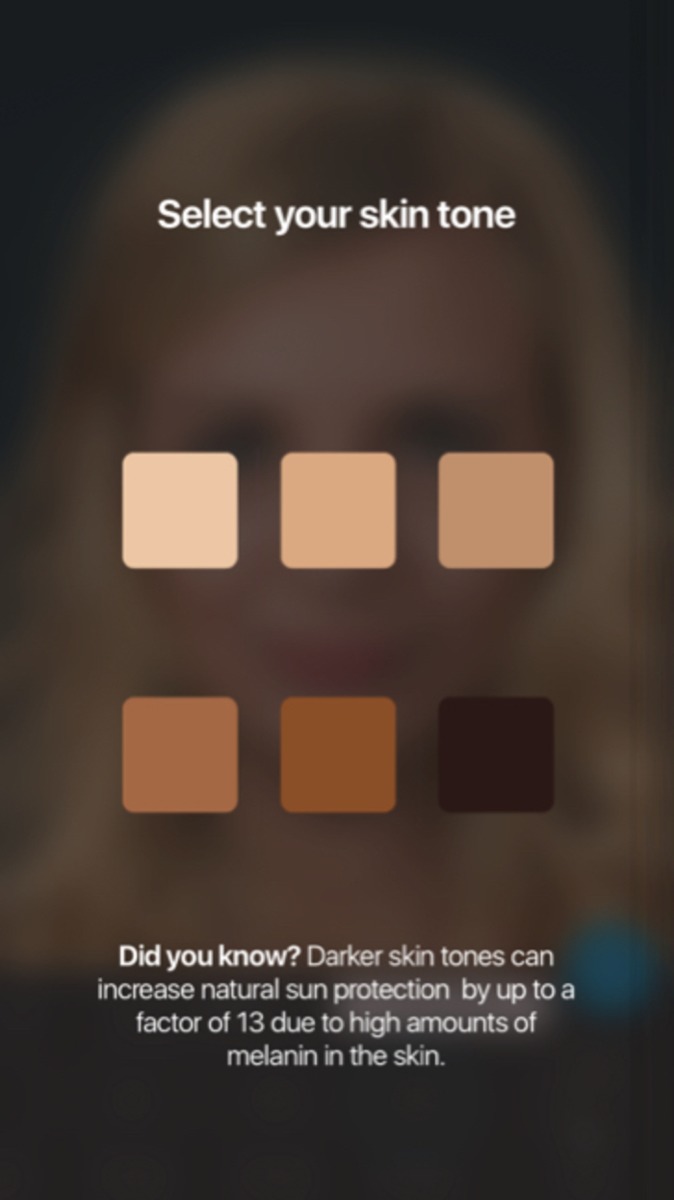

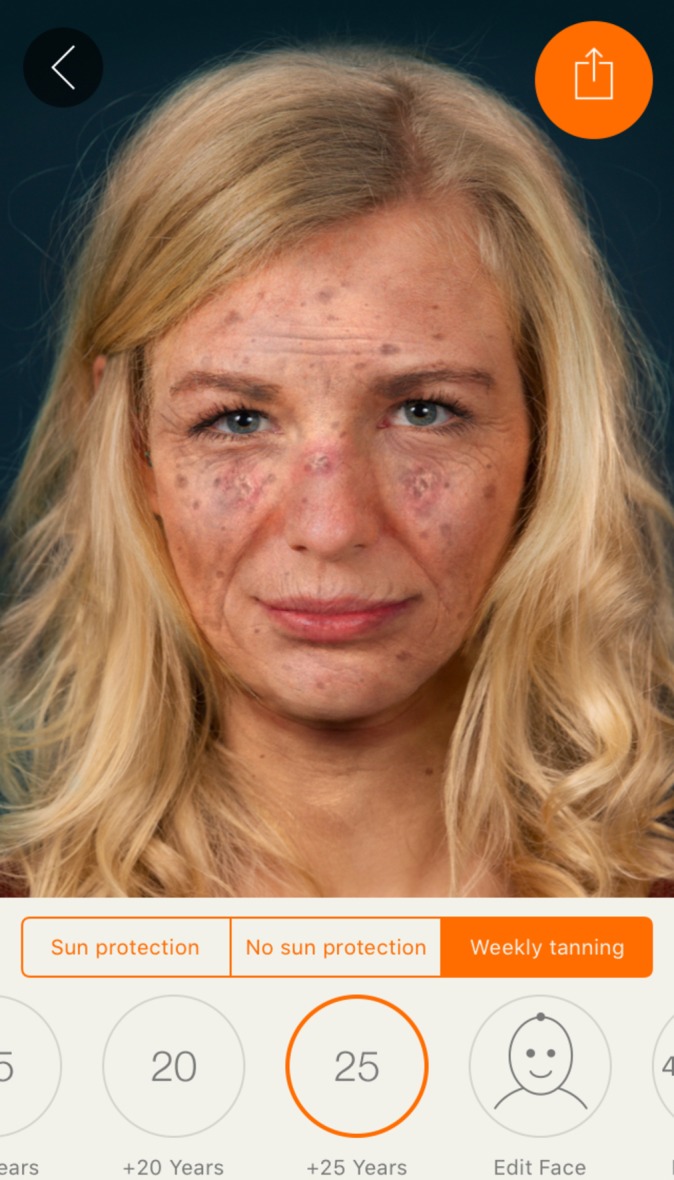

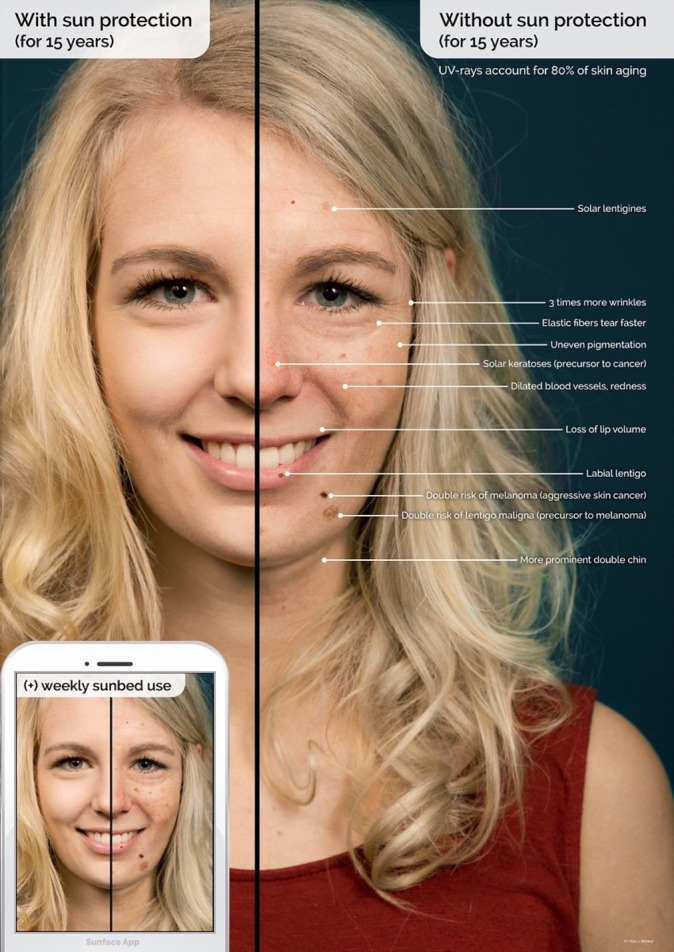

We harnessed the widespread availability of mobile phones and adolescents' interest in appearance to develop the free mobile phone app ‘Sunface,’ which enables the user take a selfie and then offers three categories: ‘daily sun protection’, ‘no sun protection’ and ‘weekly tanning,’ showing the altered face at 5–25 years in the future (figures 1–4). All effects are based on the individual skin type that the user can choose at the start of the app (figure 5). The app also shows the most common UV-induced skin cancers via extra buttons and calculates how the OR is increased with different behaviours. In addition, the app gives advice on sun protection, explains the facial changes and encourages skin examinations using the ABCDE rule (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variety, Diameter and Evolution59).

Figure 1.

Effect view: 25 years of skin ageing with sun protection.

Figure 2.

Effect view: 5 years of skin ageing with sun protection.

Figure 3.

Effect view: 5 years of weekly tanning without sun protection.

Figure 5.

Start screen of the app prompts the user to pick his skin type.

Figure 4.

Maximum effect view: 25 years of UV damage due to weekly tanning.

Afterwards, the app offers many sharing options (animated video or photo) with family and friends. By this means, the social network of the user may also be informed about the various photoageing effects of excessive UV exposure and potential health consequences, as well as potentially learning about the benefits of using the app.60

To produce realistic effects (figure 6) and to show the user realistic ORs for the options they choose in the app for the three most strongly associated skin pathologies, an extensive review of the current literature on UV-induced skin damage61 62 was conducted for each specific skin type. As no trials with 25 years of follow-up were available, we had to extrapolate the current evidence on UV-induced skin damage for the specific skin types. The evidence consists of more than 50 publications to create realistic effects from a clinician’s standpoint (which may differ from what the average person perceives as realistic).

Figure 6.

Explanatory graphic of the effects within the app.

We recently implemented this app in two German secondary schools via a method called mirroring. We ‘mirrored’ the students’ altered three-dimensional (3D) selfies on mobile phones or tablets via a projector in front of their entire grade. Using an anonymous questionnaire, we then measured sociodemographic data as well as risk factors for melanoma and the perceptions of the intervention on a 5-point Likert scale among 205 students of both sexes aged 13–19 years (median 15 years).

In our pilot study, we found more than 60% agreement in both items measuring motivation to reduce UV exposure and only 12.5% disagreement: 126 (63.0%) agreed or strongly agreed that their 3D selfie motivated them to avoid using a tanning bed, and 124 (61.7%) agreed or strongly agreed to increase use of sun protection; only 25 (12.5%) disagreed with both items. However, no effects on actual behaviour could be measured due to the cross-sectional design of the study.63

This randomised trial was designed to answer the following questions:

Is the implementation of the app in secondary schools in southeastern Brazil effective in encouraging daily sunscreen use among adolescents? Is it equally effective for both genders? Is it effective for the most sensitive skin types? How does the app intervention change the attitudes towards sun protection in accordance with the theory of planned behaviour (TPB)?64

Methods and analysis

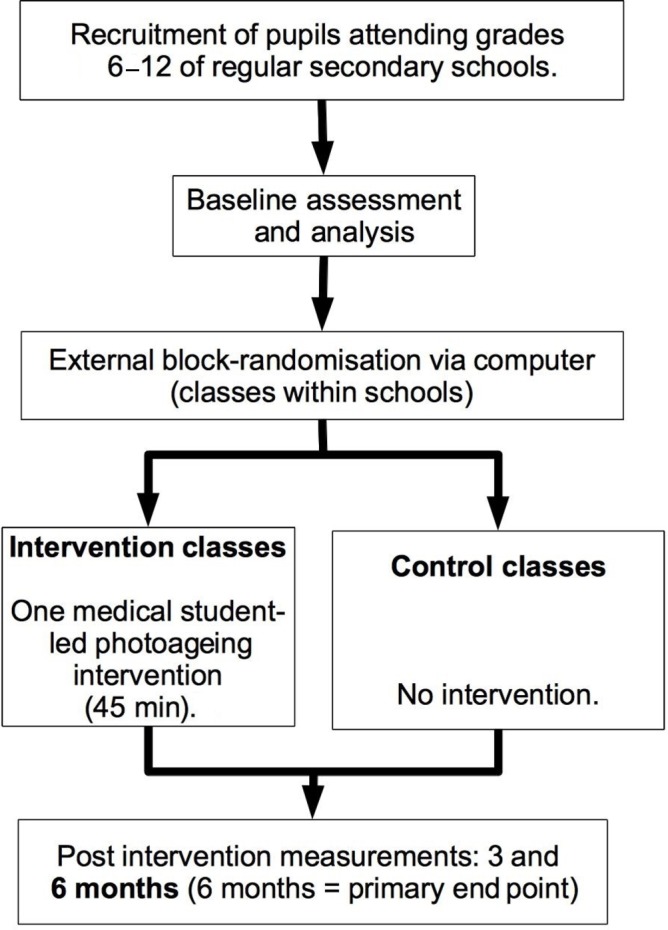

Study design

The Sunface trial is designed as a randomised controlled superiority trial with two parallel groups. Our primary end point is the difference between the two groups in daily sunscreen use (past 30 days) from baseline to 6-month follow-up (figure 7). The planned study period is February 2018 to November 2018. The study groups will consist of randomised classes receiving the intervention and control classes within the same schools (no intervention). Randomisation is externally and centrally performed at the school level with a 1:1 allocation (control to intervention) via computer.12 A total of at least 60 secondary school classes in Itauna, Brazil will participate in the teacher-supervised baseline survey in February 2018, which is conducted by trained data collectors. One week after the baseline survey, the intervention classes receive a 45 min app-based intervention conducted by local medical student volunteers. Follow-up surveys will be conducted at 3 and 6 months postintervention (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Study design.

Intervention

The school-based intervention under evaluation consists of a 45 min educational module in the classroom setting using a photoageing app. The intervention is presented by two medical students per classroom to approximately 21 students at a time. The goal is to initiate and guide the student evaluation process of skin cancer prevention with age-appropriate information that helps the students reframe positive opinions and views regarding sun protection habits in a gain-framed and interactive manner.

To integrate app-based photoageing interventions into a school-based setting, we previously developed and tested the mirroring approach in a pilot study.52 Mirroring means that the students’ altered 3D selfies on smartphones or tablets are ‘mirrored’ via a projector in front of the entire class. The mirroring approach is implemented by medical student volunteers from the University of Itauna, who receive standardised training in advance. To ensure the participation of all students within a certain class and to avoid contamination within schools, we will implement the mirroring intervention via 10 Samsung Galaxy Tablets that are already set up and brought to the schools by the volunteers.

In the first 10 min phase, the displayed face of one student volunteer is used to show the app’s altered features in the three categories to the peer group, providing an incentive for the rest of the class to test the app. Students can interact with their own animated face via touch (see online multimedia supplementary appendix 1). In front of their peers, they will be able to display their image as a non-sun protection user/sun protection user/weekly tanning bed user at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years in the future (see figures 1 and 2). Multiple device displays can be projected simultaneously, which are used to consolidate the altered measures with graphics (eg, to explain wrinkle formation). We implement mirroring with Galaxy Tab A (Samsung) via Apple’s proprietary AirPlay interface using the Android app ‘Mirroring360’ (Splashtop).

bmjopen-2017-018299supp001.mp4 (1MB, mp4)

In the second 15 min phase, students are encouraged to try the app on one of the tablet computers. The number of provided tablet computers was calculated so that the phase would take up to 12 min at the most after factoring in a usage time of approximately 4 min per student. By this calculation, 25 min of the mirroring intervention and 10 provided tablets were sufficient to have every student within a class of 40 pupils successfully photoaged at least once.

In the following 15 min, the remaining functions of the app are discussed with the students: facial changes, the ABCDE rule and the guidelines for sun protection are addressed in an interactive setting. At the end of the classroom seminar, we ask for the students’ final judgements on daily sunscreen use to create positive peer pressure and influence the students’ subjective norm in accordance with the TPB.64

In the last 5 min, the perception of the intervention by the students is measured directly after the intervention in an anonymous survey on a 5-point Likert scale via four items: (1) ‘The animation of my 3D selfie motivates me to use daily sunscreen’, (2) ‘I learned new benefits of sun protection’, (3) ‘The intervention motivates me to check my skin with the ABCDE rule in the next 6 months’ and (4) ‘The intervention was fun’.

Participants

Eligibility criteria at baseline

Students from Itauna in Southeast Brazil attending grades 6 to 12 in all types of regular secondary school are eligible.

Contaminated classes

All classes will be included in the final intention-to-treat analysis. However, app use will be assessed in both groups at 6-month follow-up to assess contamination of control classes and will be the basis for a secondary (sensitivity) analysis with the methods described in the Analysis section of this protocol.

Procedure

The schools are recruited via email, telephone and personal appointment (in most cases with the principal). Reasons for non-participation are not recorded. Data are collected via a paper–pencil questionnaire. In addition to sociodemographic data (age, gender and school type), the questionnaire captures the Fitzpatrick skin type, the ancestry of the school students65 and the frequency of sunscreen use in the past 30 days as well as other sun protection behaviours. These items are based on the Sun Exposure and Protection Index questionnaire66 and were either used in their original form or adapted to the specific circumstances of the present study. No Portuguese equivalents of the instruments were available; thus, we used the conceptual method for translation described by the WHO/UNESCAP (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia) Project on Health and Disability Statistics.67 Newly translated and/or modified items were extensively pretested and subjected to statistical analyses (internal consistency/Cronbach’s α and exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, which represented the basis for item selection).

Data collection

Each data collector received training for data collection and was required to use an adapted standardised protocol for data collection, an optimised version of that used in the Smokerface randomised trial.68

Cluster randomisation

In accordance with the guidelines for good epidemiological practice, classes within schools are externally and centrally randomly assigned to the control or intervention group via block randomisation in a 1:1 ratio (control to intervention) via computer by a statistician at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. Stratification will be performed by grade.

Outcomes

The primary end point is the difference in the 30-day prevalence of daily sunscreen use between both groups at 6-month follow-up. Secondary end points include the difference in daily sunscreen use at 3-month follow-up, if a self-skin examination in accordance with the ABCDE rule59 was performed within the 6-month follow-up and the number of tanning sessions in the past 30 days. For all end points, the number needed to treat will also be calculated. A daily sunscreen user is defined as a pupil who claims to have used sunscreen daily or almost daily in the 30 days preceding the survey.

Statistical considerations

Sample size calculation

We calculated sample sizes of 630 in the intervention group and 630 in the control group, which were obtained by sampling 30 classes with 21 students each in the intervention group and 30 classes with 21 students each in the control group to achieve 80% power to detect a prevalence difference between the groups of 5%. The daily sunscreen prevalence was assumed to be 6% under the null hypothesis and 11% under the alternative hypothesis based on a small pilot survey with 150 students in Itauna. The test statistic used is the two-sided score test (Farrington & Manning). The significance level of the test is 0.05. Normal class size in Brazil is 35 pupils; a lost to follow-up effect of 40% was taken into account.

Data entry

Data entry will be supported by the current software version of Formic Fusion by Xerox AG (Kloten, Switzerland) and the recommended scanners.

Analysis

To examine baseline differences in pupils’ characteristics in our experimental design, we will use χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. To test for between-group differences in baseline and follow-up daily sunscreen use in the past 30 days, we will use a cluster-adjusted Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test69 with a significance level of 5% (two-sided). For the main analysis, hierarchical linear models (HLMs) will be applied. HLM can handle the nested structure of the data and will be used to test for between-group differences in within-group changes in sun protection behaviour over time. HLM will also be used to investigate the influence of further covariates (such as gender, European ancestry and skin type) and time-dependent behaviour in secondary analyses. Statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS Statistics V.24.

The effect that missing data may have on results will be assessed via sensitivity analysis. Dropouts (essentially participants who withdraw consent for continued follow-up or who are missing from the classroom during the survey) will be included in the analysis and multiple imputation will be used to estimate the treatment effect.70

Discussion

This is the first cluster-randomised school-based trial on photoageing skin cancer prevention and the first trial on medical student-delivered school-based skin cancer prevention worldwide. While classic health educational school-based approaches in skin cancer prevention were evaluated as inferior to appearance-based approaches,19 there is a global lack of novel, innovative strategies that harness current technology while taking widely accepted theories for behavioural change into account.64 Although multiple studies have shown that skin cancer risk is predominantly associated with sun exposure early in life, there is often a lack of awareness in risk groups.

Thus, this trial provides the opportunity to evaluate an innovative, highly scalable, appearance-based intervention in a high-risk population. It will also provide data to estimate whether photoageing mobile apps have the potential to be broadly implemented in schools via the mirroring intervention but also via other avenues (ie, posters68 or smartphone-based advertising campaigns in the App Store and Google Play Store) or could be a valuable addition to existing educational programmes. Additionally, because it is delivered by medical students, this trial also sensitises future physicians to the importance of skin cancer prevention, highlighting their associated responsibilities within communities.35 71

According to the TPB, the subjective norm and the expected self-efficacy of the participants play a substantial role in their resulting behaviour. For example: What do their peers think about tanning? Is the result of tanning regarded as attractive and does it therefore increase one’s chances of finding a boy/girlfriend? How likely is it that a behavioural change can positively influence this reaction? The mirroring intervention triggers strong reactions of the peer group of the individual participant towards their photoaged future self (=affecting subjective norm) but also illustrates the power of one’s own behavioural change (and thereby increases one’s expectation of self-efficacy, another predictor of the TPB) to influence this reaction by peers.52

Limitations

Because this study is conducted only in Brazil, the results may not be generalizable to other cultural or national settings. However, the theoretical basis for this intervention (the TPB) has been proven to apply to most cultural contexts around the globe.64 As this trial enrols approximately 10 different public schools, it should be representative for most school types.

We must choose classes and not schools as a cluster due to sample size limitations; thus, cluster effects cannot be entirely excluded. However, multiple steps are taken to limit contamination between the control and intervention classes (ie, the name of the app is not mentioned to the pupils by the trained medical students and the teachers of the control classes are strictly prohibited to talk about the intervention with their students). Cluster effects are also monitored in the end line questionnaire and provide a basis for a sensitivity analysis.

Some students may find the effects of the Sunface app unrealistic, as indicated in our recently published pilot study. However, this does not appear to attenuate motivation to adhere to UV protection behaviour.63

In summary, we evaluate the long-term effects on behaviour of a novel method that integrates photoageing in a school-based skin cancer prevention programme in a population with a high risk for developing skin cancer. The programme affects the students’ peer group and also considers predictors for tanning.

Ethics and dissemination

Participation is voluntary and oral consent is sufficient. The ethics committee of the University of Itauna waived the necessity for informed written consent. All participant information will be stored in locked file cabinets in areas with limited access. The participants’ study information will not be released outside the study without the written permission of the participant. Results will be disseminated at conferences, in peer-reviewed journals and on our websites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating schools, students, volunteering medical students and teachers who helped to organise the classroom visits in the city of Itauna.

Footnotes

Contributors: TJB initiated the study, invented, designed and organised the intervention, wrote the manuscript, drafted the design of the study and will perform the statistical analyses. BB-S participated in the conception of the study. MVH, MCK, YN, MG, FB and DS contributed to the design of the study and data analyses and proof-read the manuscript. BB-S and OCL contributed to the design and logistics of the study, assisted with the translation of classroom materials and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. BLF, OMdF, HAL and ACCO will conduct data entry and coordinate/conduct the intervention in Brazil. They also supported the translation of the classroom materials and proof-read the manuscript. All authors declare responsibility for the data and findings presented and have full access to the final trial dataset.

Funding: The tablets are funded by the Young Research Award Research Grant from La Fondation La Roche Posay awarded to TJB for his research on the Sunface app. The University of Itauna will contribute by providing logistic support for the project and copies of all questionnaires.

Disclaimer: La Fondation La Roche Posay (LA FONDATION LA ROCHE-POSAY, Att : Cécile Voletm 62 quai Charles Pasqua, 92300 LEVALLOIS PERRET, France) and the University of Itauna Funding Board had no role in the design and conduction of this study or in the preparation, review or approval of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Itauna.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Livingstone E, Windemuth-Kieselbach C, Eigentler TK, et al. . A first prospective population-based analysis investigating the actual practice of melanoma diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1977–89. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet Editorial Board. Skin cancer: prevention is better than cure. Lancet 2014;384:470 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61320-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green AC, Williams GM, Logan V, et al. . Reduced melanoma after regular sunscreen use: randomized trial follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:257–63. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghiasvand R, Weiderpass E, Green AC, et al. . Sunscreen use and subsequent melanoma risk: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3976–83. 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nijsten T. Sunscreen use in the prevention of Melanoma: common sense rules. Virginia, USA: American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ou-Yang H, Jiang LI, Meyer K, et al. . Sun protection by beach umbrella vs sunscreen with a high sun protection factor: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:304–8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benvenuto-Andrade C, Zen B, Fonseca G, et al. . Sun exposure and sun protection habits among high-school adolescents in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Photochem Photobiol 2005;81:630–5. 10.1562/2005-01-25-RA-428.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purim KSM, Wroblevski FC. Sun exposure and protection among medical students in curitiba (PR). Rev bras educ med 2014;38:477–85. 10.1590/S0100-55022014000400009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schalka S, Steiner D, Ravelli FN, et al. . Brazilian consensus on photoprotection. An Bras Dermatol 2014;89:1–74. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haack RL, Horta BL, Cesar JA. [Sunburn in young people: population-based study in Southern Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica 2008;42:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva AA. Outdoor Exposure to Solar Ultraviolet Radiation and Legislation in Brazil. Health Phys 2016;110:623–6. 10.1097/HP.0000000000000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima AS, Stein CE, Casemiro KP, et al. . Epidemiology of melanoma in the South of Brazil: study of a city in the Vale do Itajaí from 1999 to 2013. An Bras Dermatol 2015;90:185–9. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez VL, Silva TB, Vieira MA, et al. . Melanoma characteristics in Brazil: demographics, treatment, and survival analysis. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:4 10.1186/s13104-015-0972-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amancio CT, Nascimento LF. Cutaneous melanoma in the State of São Paulo: a spatial approach. An Bras Dermatol 2014;89:442–6. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naser N. Cutaneous melanoma: a 30-year-long epidemiological study conducted in a city in southern Brazil, from 1980-2009. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:932–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo JA, Fisher DE. The melanoma revolution: from UV carcinogenesis to a new era in therapeutics. Science 2014;346:945–9. 10.1126/science.1253735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu S, Han J, Laden F, et al. . Long-term ultraviolet flux, other potential risk factors, and skin cancer risk: a cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1080–9. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton MK. Indoor tanning increases melanoma risk, even in the absence of a sunburn. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:367–8. 10.3322/caac.21248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuong W, Armstrong AW. Effect of appearance-based education compared with health-based education on sunscreen use and knowledge: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:665–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craciun C, Schüz N, Lippke S, et al. . Facilitating sunscreen use in women by a theory-based online intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Health Psychol 2012;17:207–16. 10.1177/1359105311414955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirst NG, Gordon LG, Scuffham PA, et al. . Lifetime cost-effectiveness of skin cancer prevention through promotion of daily sunscreen use. Value Health 2012;15:261–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakoufaki M, Stergiopoulou A, Stratigos A. Design and implementation of a health promotion program to prevent the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation at primary school students of rural areas of Greece. Int J Res Dermatol 2017;3:306 10.18203/issn.2455-4529.IntJResDermatol20172505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller KA, Langholz BM, Ly T, et al. . SunSmart: evaluation of a pilot school-based sun protection intervention in Hispanic early adolescents. Health Educ Res 2015;30:371–9. 10.1093/her/cyv011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarestrup C, Bonnesen CT, Thygesen LC, et al. . The effect of a school-based intervention on sunbed use in Danish pupils at continuation schools: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:214–20. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holman DM, Fox KA, Glenn JD, et al. . Strategies to reduce indoor tanning: current research gaps and future opportunities for prevention. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:672–81. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Scaglione NM, et al. . A web-based intervention to reduce indoor tanning motivations in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci 2017;18:131-140 10.1007/s11121-016-0698-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton JL, Hillhouse J, Levonyan-Radloff K, et al. . Review of interventions to reduce ultraviolet tanning: Need for treatments targeting excessive tanning, an emerging addictive behavior. Psychol Addict Behav 2017;31:962–78. 10.1037/adb0000289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olson AL, Gaffney C, Starr P, et al. . SunSafe in the Middle School Years: a community-wide intervention to change early-adolescent sun protection. Pediatrics 2007;119:e247–56. 10.1542/peds.2006-1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller KA, Huh J, Unger JB, et al. . Patterns of sun protective behaviors among Hispanic children in a skin cancer prevention intervention. Prev Med 2015;81:303–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner D, Harrison SL, Buettner P, et al. . Does being a “SunSmart School” influence hat-wearing compliance? An ecological study of hat-wearing rates at Australian primary schools in a region of high sun exposure. Prev Med 2014;60:107–14. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buller DB, Andersen PA, Walkosz BJ, et al. . Rationale, design, samples, and baseline sun protection in a randomized trial on a skin cancer prevention intervention in resort environments. Contemp Clin Trials 2016;46:67–76. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sontag JM, Noar SM. Assessing the potential effectiveness of pictorial messages to deter young women from indoor tanning: an experimental study. J Health Commun 2017;22:294–303. 10.1080/10810730.2017.1281361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guy GP, Holman DM, Watson M. The Important Role of Schools in the Prevention of Skin Cancer. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152:1083–4. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farberg AS, Glazer AM, Rigel AC, et al. . Dermatologists’ Perceptions, Recommendations, and Use of Sunscreen. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:99–101. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isvy A, Beauchet A, Saiag P, et al. . Medical students and sun prevention: knowledge and behaviours in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e247–e251. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nanyes JE, McGrath JM, Krejci-Manwaring J. Medical students’ perceptions of skin cancer: confusion and disregard for warnings and the need for new preventive strategies. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:392–3. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SS, Nijhawan RI, Stechschulte S, et al. . Skin cancer awareness, attitude, and sun protection behavior among medical students at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:797–800. 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinker TJ, Stamm-Balderjahn S, Seeger W, et al. . Education Against Tobacco (EAT): a quasi-experimental prospective evaluation of a multinational medical-student-delivered smoking prevention programme for secondary schools in Germany. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008093 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brinker TJ, Stamm-Balderjahn S, Seeger W, et al. . Education Against Tobacco (EAT): a quasi-experimental prospective evaluation of a programme for preventing smoking in secondary schools delivered by medical students: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004909 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brinker TJ, Heckl M, Gatzka M, et al. . A skin cancer prevention photoaging intervention for secondary schools in Brazil delivered by medical students: observational study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Görig T, Diehl K, Greinert R, et al. . Prevalence of sun-protective behaviour and intentional sun tanning in German adolescents and adults: results of a nationwide telephone survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;311077:e1273–306. 10.1111/jdv.14376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider S, Diehl K, Bock C, et al. . Sunbed use, user characteristics, and motivations for tanning: results from the German population-based SUN-Study 2012. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:43–9. 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Scaglione NM, et al. . A web-based intervention to reduce indoor tanning motivations in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci 2017;18:131–40. 10.1007/s11121-016-0698-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Cleveland MJ, et al. . Theory-driven longitudinal study exploring indoor tanning initiation in teens using a person-centered approach. Ann Behav Med 2016;50:48–57. 10.1007/s12160-015-9731-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baudson TG, Weber KE, Freund PA. More than only skin deep: appearance self-concept predicts most of secondary school students' self-esteem. Front Psychol 2016;7 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wichstrøm L, von Soest T. Reciprocal relations between body satisfaction and self-esteem: a large 13-year prospective study of adolescents. J Adolesc 2016;47:16–27. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bränström R, Kasparian NA, Chang YM, et al. . Predictors of sun protection behaviors and severe sunburn in an international online study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2199–210. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Görig T, Diehl K, Greinert R, et al. . Prevalence of sun-protective behaviour and intentional sun tanning in German adolescents and adults: results of a nationwide telephone survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017. 10.1111/jdv.14376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faria BL, Brieske CM, Cosgarea I, et al. . A smoking prevention photoageing intervention for secondary schools in Brazil delivered by medical students: protocol for a randomised trial. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018589 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xavier LE, Bernardes-Souza B, Lisboa OC, et al. . A Medical Student-Delivered Smoking Prevention Program, Education Against Tobacco, for Secondary Schools in Brazil: Study Protocol for a Randomized Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6:e16 10.2196/resprot.7134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brinker TJ, Seeger W. Photoaging mobile apps: a novel opportunity for smoking cessation? J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e186 10.2196/jmir.4792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brinker TJ, Seeger W, Buslaff F. Photoaging mobile apps in school-based tobacco prevention: the mirroring approach. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e183 10.2196/jmir.6016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burford O, Jiwa M, Carter O, et al. . Internet-based photoaging within Australian pharmacies to promote smoking cessation: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e64 10.2196/jmir.2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiwa M, Burford O, Parsons R. Preliminary findings of how visual demonstrations of changes to physical appearance may enhance weight loss attempts. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:283–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cku249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brinker TJ, Owczarek AD, Seeger W, et al. . A medical student-delivered smoking prevention program, education against tobacco, for secondary schools in Germany: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e199 10.2196/jmir.7906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brinker TJ, Enk A, Gatzka M, et al. . A Dermatologist’s Ammunition in the War Against Smoking: A Photoaging App. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e326 10.2196/jmir.8743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams AL, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. . Impact of a facial-ageing intervention versus a health literature intervention on women’s sun protection attitudes and behavioural intentions. Psychol Health 2013;28:993–1008. 10.1080/08870446.2013.777965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo Presti L, Chang P, Taylor MF. Young Australian adults’ reactions to viewing personalised UV photoaged photographs. Australas Med J 2014;7:454–61. 10.4066/AMJ.2014.2253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson JK, Wayne JD, Martini MC, et al. . Early detection of new melanomas by patients with melanoma and their partners using a structured skin self-examination skills training intervention: a randomized clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152:979–85. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brinker TJ, Schadendorf D, Klode J, et al. . Photoaging mobile apps as a novel opportunity for Melanoma prevention: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e101 10.2196/mhealth.8231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D’Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, et al. . UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:12222–48. 10.3390/ijms140612222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kammeyer A, Luiten RM. Oxidation events and skin aging. Ageing Res Rev 2015;21:16–29. 10.1016/j.arr.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brinker TJ, Brieske CM, Schaefer CM, et al. . Photoaging mobile apps in school-based melanoma prevention: pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e319 10.2196/jmir.8661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior : Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, Handbook of theories of social psychology. Vol. 1 London, UK: Sage, 2012: 438–59. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bakos L, Masiero NC, Bakos RM, et al. . European ancestry and cutaneous melanoma in Southern Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:304–7. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Detert H, Hedlund S, Anderson CD, et al. . Validation of sun exposure and protection index (SEPI) for estimation of sun habits. Cancer Epidemiol 2015;39:986–93. 10.1016/j.canep.2015.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robine J, Jagger C. Translation & linguistic evaluation protocol & supporting material. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO/UNESCAP Project on Health and Disability Statistics, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brinker TJ, Holzapfel J, Baudson TG, et al. . Photoaging smartphone app promoting poster campaign to reduce smoking prevalence in secondary schools: the smokerface randomized trial: design and baseline characteristics. BMJ Open 2016;6:e014288 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Donald A, Donner A. Adjustments to the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square statistic and odds ratio variance estimator when the data are clustered. Stat Med 1987;6:491–9. 10.1002/sim.4780060408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. . Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rat C, Houd S, Gaultier A, et al. . General practitioner management related to skin cancer prevention and screening during standard medical encounters: a French cross-sectional study based on the International Classification of Primary Care. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013033 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018299supp001.mp4 (1MB, mp4)