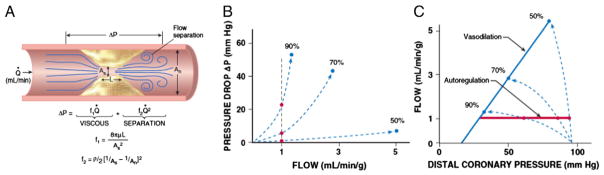

Fig. 4.

A. Fluid mechanics of a stenosis. The pressure drop across a stenosis can be predicted by the Bernoulli equation. It is inversely related to the minimum stenosis cross-sectional area and varies with the square of the flow rate as stenosis severity increases. Abbreviations: ΔP, pressure drop; Q = flow; f1, viscous coefficient; f2, separation coefficient; As, area of the stenosis; An, area of the normal segment; L, stenosis length; μ, viscosity of blood; ρ, density of blood. Interrelation among the epicardial artery stenosis pressure flow relation (B), and the distal coronary pressure-flow relation (C). Red circles and lines depict resting flow and blue circles and lines maximal vasodilation for stenoses of 50, 70, and 90% diameter reduction. As shown in panel B, the stenosis pressure flow relation becomes extremely nonlinear as stenosis severity increases. As a result, there is very little pressure drop across a 50% stenosis, and distal coronary pressure and vasodilated flow remain near normal. However, a 90% stenosis critically impairs flow and, because of the steepness of the pressure flow relation, causes a marked reduction in distal coronary pressure. Modified from Canty and Duncker6 with permission.