Abstract

Endothelial cell malignancies are rare in the Western world and range from intermediate grade hemangioendothelioma to Kaposi sarcoma to aggressive high-grade angiosarcoma that metastasize early and have a high rate of mortality. These malignancies are associated with dysregulation of normal endothelial cell signaling pathways, including the vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietin, and Notch pathways. Discoveries over the past two decades related to mechanisms of angiogenesis have led to the development of many drugs that intuitively would be promising therapeutic candidates for these endothelial-derived tumors. However, clinical efficacy of such drugs has been limited. New insights into the mechanisms that lead to dysregulated angiogenesis such as mutation or amplification in known angiogenesis related genes, viral infection, and chromosomal translocations have improved our understanding of the pathogenesis of endothelial malignancies and how they evade anti-angiogenesis drugs. In this review, we describe the major molecular alterations in endothelial cell malignancies and consider emerging opportunities for improving therapeutic efficacy against these rare but deadly tumors.

KeyPoints

Intermediate- and high-grade endothelial cell malignancies are rare, but can be associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.

HIV and KSHV viral proteins directly interact with Notch pathway and VEGF pathway proteins, contributing to the tumorigenesis of Kaposi sarcoma.

Angiosarcomas contain multiple abnormalities that may lead to primary resistance to VEGF/VEGFR inhibitors. These include VEGFR2 (KDR) and PLCG1 mutations, loss-of-function PTPRB mutations, and amplification of c-MYC and VEGFR3 (FLT4).

Treating chemotherapy-resistant endothelial malignancies with VEGF-targeted drugs has had limited success. Therefore, more effective therapies are needed.

Understanding the deregulated signaling pathways in endothelial cell neoplasms may reveal insights into driver and drug-resistance mechanisms.

Introduction

Endothelial cells are known to line established blood vessels and initiate the establishment of new blood and lymph channels in vascular development. Malignancies arising from endothelial cells are rare in developed countries; however, the tumors that do arise tend to be highly aggressive and difficult to treat. While high-grade endothelial malignancies respond well to traditional chemotherapy agents such as taxanes (Fig. 1), their durability is poor and the tumors acquire drug resistance rapidly.1 Targeted therapies such as anti-angiogenic agents that would be intuitive for these malignancies have had limited success in the clinic. Therefore, a renewed effort aimed at identifying the mechanisms by which endothelial cell malignancies evade currently available angiogenesis inhibitors is required to improve outcomes of patients with these rare diagnoses. New insights from the laboratory include identification of potential drivers of endothelial malignancies that can function as new targets for future clinical development.

Fig. 1.

Clinical appearance of angiosarcoma and response to paclitaxel. Pretreatment appearance of cutaneous angiosarcoma in a patient with lymphedema of the upper extremity following treatment for breast cancer (left), and appearance after response to paclitaxel (right)

The clinical and pathological features of endothelial cell malignancies have been reviewed previously.2–5 These tumors generally occur in adults and are classified as having intermediate or high malignant potential. Intermediate grade vascular neoplasms include epithelioid, spindle cell, psuedomyogenic, and malignant endovascular papillary hemangioendotheliomas. Each of these entities is classically differentiated by histological appearance, but recent evidence suggests that at least some of the intermediate grade hemangioendotheliomas are driven by chromosomal translocations (Table 1). Compared to other intermediate types, epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas (EHEs) of visceral origin tend to be multifocal with propensity for metastasis despite their slow proliferative rate. Histopathologically, these tumors are characterized by an epithelioid appearance with disorganized vascular channels and are sometimes mistaken for carcinomas (e.g., lung adenocarcinoma).6 The diagnosis is often made by the presence of one of several characteristic chromosomal translocations.

Table 1.

Chromosomal translocations in hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcoma

| Rearrangement | Involved gene(s) | Resultant phenotype | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| t(1;3)(p36.23;q25.1) | WWTR1, CAMTA1 | EHE | Tanas et al.,158 Anderson et al.,159 Errani et al.,160Patel et al.161 |

| t(11;X) | YAP1, TFE3 | EHE | Antonescu et al.162 |

| t(10;14) | PIGF | EHE | He et al.165 |

| t(7;19)(q22;q13) fusion | SERPINE1, FOSB | PHE | Walther et al.166 |

| 11p11.2-11q12.1 | NUP160, SLC43A3 | Angiosarcoma | Shimozono et al.169 |

WWTR1 WW domain containing transcription regulator 1, CAMTA1 calmodulin binding transcription activator 1, EHE epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, YAP1 the yes-associated protein 1, TFE3 transcription factor binding to IGHM enhancer 3, PlGF placental growth factor, SERPINE1 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1) member 1, FOSB FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B, PHE pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, NUP160 nucleoporin 160 kDa, SLC43A3 solute carrier family 43, member 3

Endothelial cell malignancies of high malignant potential include angiosarcomas and, in immunocompromised hosts, Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Angiosarcomas belong to the high-grade end of the spectrum, with an aggressive clinical course characterized by a high propensity for both local recurrence and distant metastasis. Clinically, there are two distinct subtypes. Primary angiosarcomas can occur anywhere in the body; the more common sites include the scalp, breast, liver, spleen, bone, and heart.2 Secondary angiosarcomas arise from chronic lymphedema in the extremities or from radiation exposure to the chest wall following breast cancer treatment and are often molecularly associated with amplification of c-MYC.7 KS has a viral etiology and is caused by KS-associated herpes virus (KSHV; also known as HHV8). Originally described in elderly men of Mediterranean descent, it is also associated with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and immune suppression8 and is now one of the most common malignancies in Sub-Saharan Africa.9

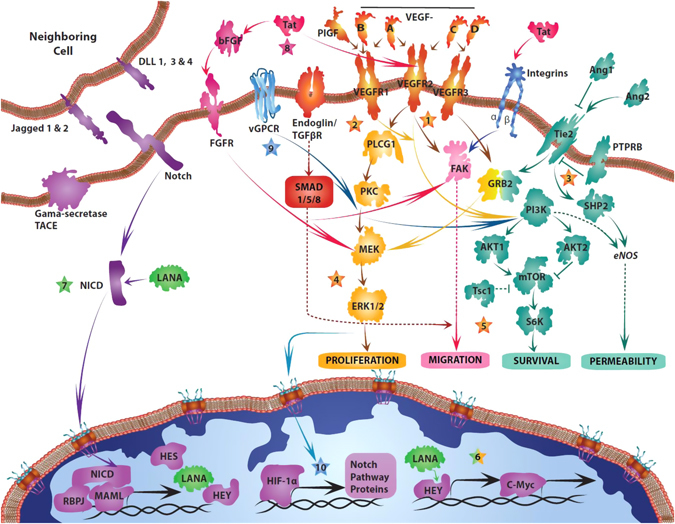

A common feature of endothelial cell malignancies is the dysregulation of normal endothelial cell signaling pathways (Fig. 2). Multiple mechanisms contribute to the observed dysregulation, including viral oncoproteins, chromosomal rearrangements, and paracrine signaling in the microenvironment. To date, targeting angiogenesis pathways has had varying degrees of success (Table 2). In this review, we summarize the existing clinical, molecular, and biological knowledge to frame a path toward a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of endothelial cell malignancies and improved clinical outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Key pathways in endothelial cell malignancies. Alterations in angiosarcoma (orange stars) include 1. Activating mutations in VEGFR2 (KDR), and amplification of VEGFR3 (FLT4), 2. A recurrent activating R707Q mutation in PLCG1, 3. Loss of function mutations in PTPRB, removing the inhibitory signal on Tie2, 4. Mutations in K-, H-, and N-RAS, BRAF, and MAPK1, and amplification of B- and C- RAF, and MAPK1. 5. Mice with loss of Tsc1 have constitutive activation of mTOR signaling and develop angiosarcoma. 6. C-MYC amplification is associated with radiation or lymphedema-induced angiosarcoma. The KSHV-derived LANA protein stabilizes HEY (6) leading to c-MYC transcription in KS cells, and stabilizes the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (7), leading to increased Notch-mediated signaling. The HIV-1 protein Tat binds to alpha-5-beta-1 and alpha-v-beta-3 integrin receptors and stimulates migration and invasion. Tat also stimulates the release of preformed, extracellularly bound bFGF into a soluble form that can induce vascular cell growth and prevent apoptosis, and Tat directly interacts with VEGFR2 leading to ligand independent activation of its downstream effectors (8). Expression of the lytic phase KSHV viral G-protein coupled receptor (vGPCR) leads to activation of the MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathways (9) which ultimately causes HIF-1a-mediated transcription of Notch-related proteins (10). Ang2 angiopoietin2, AKT protein kinase B, b-FGF basic fibroblast growth factor, BMP bone morphogenetic protein, DLL delta-like, ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2, FGFR, FAK focal adhesion kinase, FGFR fibroblast growth factor receptor, GRB2 growth factor receptor-bound protein 2, HES hairy enhancer-of-split, HEY hairy and enhancer of split related protein, HIF-1alpha hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit, LANA latency-associated nuclear antigen, MAML mastermind-like protein, MEK MAPK kinase, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, MYC Myc proto-oncogene, PLCG1 phospholipase C-gamma 1, PI3K phosphoinositide 3-kinase, PTPRB receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) beta, RBPJ recombinant binding protein suppressor of hairless, S6K P70-S6Kinase 1, TACE ADAM17, Tie2 TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial, Tsc1 tuberous sclerosis 1, VEGF(R) vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor)

Table 2.

Current status of drugs targeting deregulated signaling pathways in angiosarcoma and other endothelial cell neoplasms

| Target | Drugs | Current development status |

|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | ||

| VEGF | Bevacizumab | Phase 2 trials with RR 9% (ref. 22) and 6 month PFS 54%, median OS 19.5 months;23 no benefit over paclitaxel alone |

| Aflibercept | No published studies to date | |

| VEGFR2 | Sorafenib | Phase II with RR 0–14%, median PFS of 2–5 months24–26 |

| Sunitinib | Case reports29, 30, 35 and 2 angiosarcoma patients in large Phase 2 trial31 | |

| Pazopanib | Case reports,27, 28 Phase 2 trial ongoing (NCT01462630) | |

| Cediranib, Axitinib, Ramucirumab | No published studies to date | |

| Tie2/Ang2 | Trebananib | Phase 2, no responses in 16 patients46 |

| Notch/DLL4 | Gamma-secretase inhibitors | GEM Notch KO models develop hepatic angiosarcomas,52, 53 no clinical studies in angiosarcoma; Preclinical studies with gamma-secretase inhibitors with activity against KS cell lines126 |

| FGF | Anti bFGF oligonucleotides | In vitro activity in KS132 |

| Sunitinib | See sunitinib above | |

| PDGF/PDGFR | Imatinib | Case reports59 |

| Dasatinib | In vitro activity in canine angiosarcoma57 | |

| Olaratumab | Phase II trial in soft tissue sarcoma, including angiosarcoma (NCT01185964) | |

| Angiostatin/endostatin | Angiostatin/endostatin | Case report,62 preclinical activity in hemangioendothelioma64 |

| CD105 (endoglin) | TRC0105 | Phase 1b/2a combined with pazopanib (NCT01975519) |

| Intracellular kinase and mTOR pathways | ||

| PLCG1 | No published inhibitors in clinical development | |

| Raf | Vemurafenib, dabrafenib | No published studies to date |

| MEK | Trametinib, cobimetinib | Preclinical activity in canine angiosarcoma with single agent and combined MEK and mTOR inhibition88 |

| mTOR | Everolimus, sirolimus, temsirolimus | Preclinical studies in angiosarcoma (see above); Case report in EHE;174 Tumor regression in transplant associated KS,128 phase I study in KS combined with HAART129 |

| Transcriptional control | ||

| MYC | BET inhibitors | Not currently being tested in vascular tumors |

| Beta-receptors | Propranolol | First-line therapy for IH;175–177 preclinical studies showed synergy in angiosarcoma and EHE cell lines178 |

| Glucocorticoid receptors | Prednisolone, methylprednisolone | First-line for hemangioendothelioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome179 |

| Prednisolone | RR 90% in IH146, 147 | |

| Prednisone | Similar response rate to propranolol in a phase 2 study for proliferating IH180 | |

VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, RR response rate, PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival, VEGFR2 vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, Tie2 TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial, Ang2 angiopoietin 2, DLL4 delta-like 4, KS Kaposi sarcoma, FGF fibroblast growth factor, PDGF/PDGFR platelet-derived growth factor/ platelet-derived growth factor receptor, CD105 endoglin; mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, PLCG1 phospholipase C-gamma1, Raf Raf-1 proto-oncogene, MEK MAPK kinase, EHE epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, HAART highly active anti-retroviral therapy, MYC Myc proto-oncogene, BET bromodomain and extra-terminal domain family, IH infantile hemangioma

Physiologic angiogenesis pathways in endothelial cell malignancies

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor (VEGFR) signaling

VEGF/VEGFR2-mediated signaling is critical for tip cell selection and migration in physiological angiogenesis. VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 both promote tip cell formation, breakdown of the basement membrane, and loss of pericyte coverage, allowing for endothelial cell migration. Unsurprisingly, endothelial cell neoplasms have aberrant VEGF/VEGFR pathway signaling.

In aggressive angiosarcomas, alterations in VEGF and its receptors have been well characterized, including mutations and amplifications (Fig. 2). Angiosarcomas have high VEGF-A and VEGFR (1–3) expression, with rates ranging from 65–94% for VEGFR (1–3).10 VEGFR2 mutations have been reported in 10% of angiosarcomas11 and in 2 of 6 angiosarcomas in a smaller series,12 with mutations identified in the extracellular, transmembrane, and kinase domains. However, the prevalence of these VEGFR2 mutations in angiosarcomas remains uncertain, as no VEGFR2 mutations were revealed in other studies including whole-genome- or whole-exome sequencing.13 The functional consequence of these mutations is not fully understood, but at least some are thought to be activating mutations that act as drivers in a subset of angiosarcomas.11

Perhaps the strongest clinical correlation of VEGF/VEGFR dysregulation in angiosarcoma is the finding of VEGFR3 (FLT4) gene amplification in secondary (radiation- or lymphedema- induced) angiosarcomas.7 These amplifications are generally found in combination with other alterations such as c-MYC amplification and mutations in PLCG1 and PTPRB. Thus, although VEGFR3 drives lymphangiogenesis and induces sprouting and tip cell migration, the individual contribution of VEGFR3 amplification in these cases remains unclear. Effective targeting of the VEGF/VEGFR axis either by knocking down VEGF-A, -C, or -D, or treatment with the pan-VEGFR inhibitor axitinib in a mouse model with constitutive mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation (develop tumors consistent with lymphangiosarcoma) suggests that targeting the upstream ligand or receptor may be a therapeutic option even in cases when downstream activating mutations are identified.14 Although these alterations do not represent the primary genetic driver events, targeting VEGF/VEGFR signaling is a rational clinical approach in angiosarcoma.

VEGF signaling also contributes to the development of KS. AIDS-KS spindle cells are stimulated to secrete VEGF by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-beta and interleukin (IL)-1 beta, and co-injection of these two factors increases the vascularity of KS-like lesions in mice.15 VEGF acts as an autocrine growth factor in KS, which has high levels of VEGFR1, VEGFR2,16 and VEGFR317 compared with adjacent normal skin. Expression of the virally encoded vGPCR (discussed below) is sufficient to induce VEGF-mediated angiogenic phenotypic switching in mouse fibroblasts18 and immortalizes human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) by upregulation and activation of VEGFR219 VEGF expression is less well-characterized in other malignancies of endothelial cell origin. Some studies have reported VEGF expression in a high proportion of EHEs, and associated increased VEGF staining intensity with more aggressive disease.20, 21 Additional work is needed to fully characterize the contributions of the VEGF pathway in EHE pathogenesis.

Clinical results with anti-VEGF drugs such as bevacizumab and VEGFR2-blocking tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been disappointing in patients with endothelial cell malignancies (Table 2). The response rate to bevacizumab monotherapy was 9% (median progression free survival (PFS) of just 3 months) in patients with angiosarcoma;22 addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel did not provide additional benefit over paclitaxel alone.23 Sorafenib, a TKI with anti-VEGFR2 activity, had a similarly low response rate reaching 14.6% in patients with advanced angiosarcoma (median PFS of 2–5 months).24–26 Clinical responses to other TKIs including pazopanib27, 28 and sunitinib29, 30 have also been published in small reports, but larger phase II and III clinical trials of sunitinib31 or pazopanib32 in soft tissue sarcoma included only a limited number of patients with angiosarcomas. Similarly, some studies have reported benefit in EHE patients treated with bevacizumab, sunitinib, or pazopanib, but larger studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions about response rates. In addition, these studies lacked a control arm, making it difficult to quantify the benefit of these agents in this indolent tumor with slow progression.22, 33–35 Interestingly, in patients with KS, HAART plus bevacizumab resulted in an overall response rate of 31%, with three complete responses.36 Despite this finding, anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy is not currently used routinely in KS likely due to higher response rates with liposomal doxorubicin and taxanes.

Angiopoietin/Tie2 signaling

In contrast to VEGF signaling, which stimulates early vascular development, angiopoietin (Ang)/Tie signaling promotes endothelial cell survival and stability.37 Different Tie2 ligands, notably Ang1 and Ang2, have variable effects on Tie2 signaling. Ang1 is produced by multiple cell types, whereas Ang2 is produced primarily by endothelial cells and is expressed only in tissues undergoing remodeling.38 Ang2 can function as an agonist or antagonist depending on the environment.39 Interestingly, Ang2 is upregulated in solid tumor angiogenesis, and high levels of Ang2 are associated with worse outcomes in multiple cancer types.40

A transmembrane phosphatase, receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) beta (PTPRB), dephosphorylates Tie2, rendering it inactive.41, 42 Loss-of-function mutations in PTPRB are relatively common in angiosarcoma and were found in 26% of angiosarcomas; interestingly, all these mutations were in secondary angiosarcomas.13 Normally, PTPRB dephosphorylates Tie2; thus, loss of PTPRB in angiosarcoma likely increases Ang/Tie2 signaling and may activate multiple pathways downstream from Tie2, such as the protein kinase B (AKT)/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/mTOR, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and downstream of kinase-related protein/non-catalytic region of tyrosine kinase adaptor protein 1/p21-activated protein kinase (DOCK/NCK/PAK) pathways.40 Silencing PTPRB in HUVECs led to increased sprouting, even in the presence of VEGFR2 inhibitors such as sunitinib, demonstrating that PTPRB loss represents a mechanism of canonical activation of Tie2 signaling in angiosarcoma.13

Ang2 is highly expressed in angiosarcoma, and higher Ang2 secretion is correlated with more advanced angiosarcoma stage; in contrast, Ang1 seems to have a minimal role in angiosarcoma43 and higher Ang1 expression correlates with improved survival.44 Ang2, Tie1, and Tie2 are strongly expressed in both angiosarcoma and KS samples.44, 45 The correlation of increased Ang2 expression with worse outcomes and that of increased Ang1 expression with improved survival suggests that these ligands may be promising therapeutic targets. However, in a phase II study of trebananib, a peptibody against both Ang1 and Ang2, no responses were seen in angiosarcoma patients. Trebananib increased Ang1 and Ang2 levels after treatment, likely contributing to the lack of response.46 Additionally, antagonizing Ang1 may diminish its seemingly beneficial effect. Given the differential effects of Ang1 and Ang2, a better approach may be to target Ang2 independently with a specific agent.

Notch signaling

In physiological vascular development, Notch signaling is active at endothelial tip cells, where increased DLL4 expression stimulates Notch signaling in neighboring stalk cells and inhibits them from migrating, thus promoting organized vascular branching.47 Upon ligand binding, Notch receptors are cleaved by regulated proteolysis and the cleaved intracellular component travels to the nucleus and interacts with hairy and enhancer of split related-2 (HERP-2/Hey-1) and hairy enhancer-of-split (HES) proteins, leading to transcription (Fig. 2).48 The Notch ligand Jagged1 has a pro-angiogenic effect, whereas DLL4 counters the proliferative effects of VEGF49 and Jagged1.50

The observation of endothelial neoplasms forming after DLL4 inhibition in mouse models implicated Notch signaling in the development of proliferative vascular tumors, especially in the liver.51 Conditional knockout of Notch1 in the liver in a mouse model resulted in hepatic angiosarcomas in 86% of mice by 50 weeks.52 Studies in a separate mouse model confirmed that loss of Notch1 heterozygosity leads to endothelial cell neoplasms of varying histological grade with approximately the same penetrance; interestingly, the liver was the primary site.53 However, few, if any, significant Notch abnormalities have been identified in the sequencing efforts of human angiosarcoma samples, and the clinical relevance of these observations remains to be determined. Notch pathway targeted therapies such as DLL4 inhibitors and Notch receptor antagonists have effects that would mechanistically lead to disorganized vascularization as seen in the mouse models, and are, therefore, not being tested in angiosarcoma. In other cancer types, Notch has oncogenic or tumor suppressor roles depending on context, and it similarly can have pro- or anti--angiogenic effects in physiological tissue remodeling. The potential effect of nonspecific Notch inhibition with gamma-secretase inhibitors on hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma remains to be determined. A pathogenic role for the Notch pathway, with druggable targets for therapeutic development, is more established in KS tumorigenesis primarily due to the effects of KSHV proteins on endothelial cells. This is described in more detail below. While these observations reflect the importance of this pathway in deregulation of angiogenesis, targeting Notch signaling is complicated by several unique features of this pathway. Effects of Notch are remarkably context dependent and the signal itself has dose-dependent effects downstream. Furthermore, Notch signal tends to have a very short intracellular half-life and sustained inhibition may not be needed. To utilize Notch inhibitors in treatment of angiosarcoma, it would be important to identify the optimal level and timing of inhibition for disease control without excessive toxicity.

Other angiogenesis-related pathways in endothelial cell malignancies

Platelet-derived growth factor

Paracrine signaling between endothelial cells and perivascular cells is mediated, in part, by PDGF signaling. Endothelial cells secrete PDGF-BB, which increases pericyte coverage and maintains the integrity of the endothelial cell basement membrane.54 At least five different PDGF isoforms interact with two different PDGF receptors (PDGFRs).55 PDGFR activation results in autophosphorylation of the receptor, which in turn activates phospholipase C-gamma (PLCG).56 As described below, PLCG1 activation by VEGFR2 acts as a driver for a subset of angiosarcomas and leads to resistance to VEGF/VEGFR targeted therapies. Treatment with dasatinib or imatinib, which inhibit PDGFR as well as other kinases, decreased cell viability in vitro and decreased tumor growth in vivo in a canine xenograft model of hemangiosarcoma.57 Isolated responses to imatinib, a PDGFR inhibitor, have been noted in patients with angiosarcoma.58, 59 A recently completed clinical trial of olaratumab, a monoclonal antibody against PDGFR-alpha, combined with doxorubicin (NCT01185964) for soft tissue sarcoma showed promising results including an improvement in overall survival; olaratumab has not been evaluated for treatment of angiosarcoma. Endothelial cell malignancies contain disorganized endothelium, and have not been proven to be associated with pericytes in the same way as normal endothelial cells.

Angiostatin and endostatin

Angiostatin and endostatin are protein fragments that suppress tumor growth and angiogenesis.60, 61 Endostatin has been used to treat angiosarcoma, but its effectiveness could not be determined because it was given in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.62 The vast majority (>90%) of endothelial cell neoplasms including benign hemangiomas, EHEs, and angiosarcomas express annexin II, an angiostatin receptor.63 Angiostatin inhibits hemangioendothelioma growth in vivo, but does not affect proliferation or induce apoptosis in vitro.64 Interestingly, endostatin paradoxically stimulates hemangioma-derived endothelial progenitor cells in an in vitro migration assay, a phenomenon not observed in hemangioendothelioma cells.65, 66 Although angiostatin and endostatin are sometimes used in patients with endothelial cell malignancies, more evidence is needed to fully assess their potential benefits.

Endoglin/transforming growth factor beta

Endoglin (CD105) is a component of the transforming growth factor beta receptor family that is expressed on endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and monocytes and has been specifically considered a drug target for novel agents designed to target tumor angiogenesis.67, 68 In physiological angiogenesis, endoglin mediates TGF-beta signaling via activin a receptor type II-like 1 (ALK1), which acts as a pro-angiogenic mediator and increases endothelial cell migration and proliferation, counteracting the potential inhibitory effect of TGF-beta on endothelial cells.69 There are two isoforms of endoglin, with S-endoglin playing a critical role in vascular senescence.70 Endoglin mutations cause hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1, which is characterized by vascular dysplasia and hemorrhage,71 but to date no mutations in endoglin have been identified in endothelial cell neoplasms. Angiosarcomas have high expression levels of endoglin, with 95–100% staining positive.72, 73 Levels of TGF-beta pathway proteins are higher in angiosarcoma of bone than in primary angiosarcomas of soft tissue.74 However, the importance of endoglin in mediating the observed increase in TGF-beta signaling in bone angiosarcoma is not established, and the near universal expression of endoglin in angiosarcomas regardless of their site of origin makes any causative presumptions premature without additional study. An anti-endoglin antibody is currently being tested in clinical trials in combination with pazopanib for soft tissue sarcoma, with preliminary results in a phase I/II trial showing 2/2 patients with complete response, suggesting efficacy in angiosarcoma that requires further investigation (NCT01975519).75

Intracellular oncogenic signaling pathways

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

In normal endothelial cells, VEGF induced VEGFR endocytosis and regulated MAPK activation are important factors that stabilize filopodia-carrying endothelial sprouts and ensure that a transient signal allows for stability in a branching vessel.76 VEGFR2 activation leads to PLCG1 phosphorylation and transduces the activating signal of its binding ligand to ensure normal vascular function.77–80 Autophosphorylation of VEGFR2 leads to the recruitment of PLCG1, binding of PLCG1 at its N-terminal SH2 domain, and subsequent activation of PLCG1 (ref. 81). Phosphorylation at PLCG1-Y783 causes a conformational change that relieves the auto-inhibition of the C-terminal SH2 domain, and leads to downstream signaling.82, 83 Activated PLCG1 catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, leading to protein kinase C-dependent MAPK signaling.84, 85 A recurring mutation in PLCG1, R707Q, has been identified in angiosarcoma, with a prevalence of 9–30% (refs 12, 13). R707 is in the auto-inhibitory SH2 domain of PLCG1, and the missense mutation is hypothesized to destabilize this domain and reduce its auto-inhibitory effect.13 Indeed, canonical activation was demonstrated by expressing the PLCG1-R707Q in HUVECs, which resulted in the downstream activation of MAPK and NFAT-mediated signaling irrespective of PLCG1 activation by VEGFR2 (ref. 12). Interestingly, sequencing from a patient with progression following initial response to sunitinib revealed a PLCG1-R707Q mutation in the metastasis, but this mutation was not found in the primary tumor. This finding suggests a mechanism by which angiosarcomas could develop adaptive resistance to VEGFR-targeted therapy.86 In addition to PLCG1 mutations, mutations or amplifications in K-, H-, and N-RAS, B- and C-RAF, and MAPK1 were identified in angiosarcoma.87 Preclinical studies with canine angiosarcomas have demonstrated anti-tumor activity with MEK inhibition.88

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is frequently activated in many cancer types. In normal endothelial cells, this pathway is activated through several stimuli, including VEGF, Ang/Tie2, and integrins.89 AKT is phosphorylated compared to normal adjacent endothelial cells in nearly all endothelial cell neoplasms.90, 91 Interestingly, different AKT isoforms have opposing effects. In hemangioma, hemangioendothelioma, and angiosarcoma models, AKT1 has been demonstrated to promote growth and migration, whereas AKT3 inhibits growth.90 Overexpression of AKT1 is sufficient to create proliferative neoplasms, but without the ability to metastasize.92

Downstream in the PI3K pathway, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) activation leads to the activation of p70 S6-kinase and S6 ribosomal protein. Angiosarcomas have increased activation of S6-kinase and S6 ribosomal protein; topical rapamycin inhibits the growth of patient-derived infantile hemangioma (IH) cells and established hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma cell lines in vitro and the growth of hemangioendothelioma mouse xenografts.93

Mice with a conditional knockout of tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (Tsc1), a negative regulator of mTORC1, develop paw angiosarcomas at 6 weeks that are responsive to rapamycin.94 The sustained mTORC1 signaling that results from Tsc1 loss leads to increases in HIF1-alpha and c-MYC-mediated VEGF transcription, creating an autocrine loop that is required for tumor maintenance.14 Although canine angiosarcoma xenografts in athymic nude mice showed minimal response to temsirolimus alone, temsirolimus sensitized angiosarcomas to MEK inhibition, suggesting cross-talk between the MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways.88 Although the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is activated in angiosarcoma, this activation does not appear to be due to mutations or losses directly affecting this pathway, such as phosphatase and tensin homolog loss or PI3K mutations.95 Targeting the pathway with mTOR inhibitors remains a promising therapy and is currently used for patients with angiosarcoma in the investigational setting.

Transcriptional regulation

Myc proto-oncogene (MYC)

Dysregulation of the transcription factor MYC has been implicated in many cancer types.96 MYC amplification is well described in secondary angiosarcoma7, 97 and has also been demonstrated in primary angiosarcoma.98 In addition to MYC, Ret proto-oncogene (RET) signaling is upregulated and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C is downregulated in secondary angiosarcoma,99 which is in agreement with the finding that N-MYC is a downstream target of Ret that downregulates cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p18, leading to proliferation of cultured fibroblasts.100 MYC may contribute to the aggressive angiogenic phenotype of angiosarcoma by upregulating miR-17-92 and thus downregulating thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), an angiogenesis inhibitor.101 Genomic analyses revealed that MYC-related pathways were upregulated in murine angiosarcoma cell lines isolated from primary hepatic angiosarcomas in Notch1 conditional knockout mice.102 Interestingly, mice in which Cdk6 activity is increased by rendering them insensitive to inhibition by INK4 develop angiosarcomas with a high prevalence (~50%), particularly when the Cdk6 alteration is introduced in a p53 heterozygous or null background.103 To date, Cdk4/6 inhibitors have not been evaluated in angiosarcoma, but could represent an important opportunity.

MYC also plays an important role in KS pathogenicity. The KSHV virus protein LANA stabilizes c-MYC by preventing its phosphorylation at Thr58, thus preventing apoptosis.104 In primary effusion lymphoma, another malignancy associated with KSHV, MYC is required to maintain the latency of KSHV,105 and inhibition of bromodomain and extra-terminal domain bromodomain (BET), a therapeutic strategy for targeting pathologic MYC activation,106 has had promising results in vitro in other KSHV associated tumors.107 In other models, MYC has been shown to promote neovascularization by either downregulating anti-angiogenic factors such as TSP1 and connective tissue growth factor108 or interacting with hypoxia to induce VEGF-A production.109 The latter mechanism, which used a model for dermal angiogenesis, may be particularly relevant in endothelial cell tumors that commonly arise in the skin.

HIF/hypoxia

Under normoxic conditions, the transcription factor HIF-1a is primed for degradation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL), an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Hypoxia leads to HIF-1a-mediated pro-angiogenic signaling and consequently the recruitment of blood vessels to solid tumors. In mice, removal of VHL’s inhibition of HIF via mosaic VHL knockout led to the formation of vascular lesions ranging from hemangiomas to a single mouse that developed an angiosarcoma.110 HIF-1a and HIF-2a expression is reported in a subset of angiosarcomas,111, 112 but HIF-1a does not appear to be a notable driver of angiosarcoma growth.112

On the other hand, HIF-1a and hypoxia-related pro-angiogenic pathways play a role in the transition of KSHV-infected endothelial cells to KS.113 A G protein-coupled receptor encoded by KSHV (vGPCR) contains an activating V138D mutation, which leads to agonist-independent induction of the MAPK and p38 signaling pathways. This, in turn, leads to HIF-1a phosphorylation and a HIF-1a-dependent increase in VEGF secretion.114 In addition, vGPCR also increases mTOR complex signaling, suggesting that multiple pathways activated by vGPCR converge on HIF-1a-mediated VEGF transcription and secretion.115 HIF-1a-mediated transcription is also induced by the KSHV LANA protein, by targeting the HIF-1a suppressors VHL and p53 for degradation,116 as well as by direct protein–protein interactions between LANA and HIF-1a that stabilize HIF-1a and promote its translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 2 117).

Viral oncoproteins in KS

The discovery of KSHV led to discoveries regarding the oncogenic role for the virus (reviewed in ref. 118). Here, we focus specifically on KSHV and its direct role in co-opting physiologic angiogenesis to lead to transformation of endothelial cells to Kaposi spindle cells.

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus

Like other herpes viruses, KSHV infection consists of two phases: the lytic phase in which the virus infects the host cell and replicates and the latent phase in which the viral DNA remains in the host cell but is not actively replicating. Viral proteins specific for both phases directly interact with components of angiogenic signaling to promote tumorigenesis. Specifically, the latency associated proteins LANA and vFLIP induce Notch ligands Jagged1, and DLL4. LANA stabilizes Hey1,119 leading to decreased Hey1 degradation and consequently increased endothelial cell proliferation.120 Furthermore, KSHV harnesses Notch signaling to induce its lytic phase by utilizing RBP-J, a key transcription factor for Notch related genes, to initiate transcription of its lytic phase genes.121 vIL-6, a lytic phase protein, induced expression of Notch4, DLL1, DLL4, and downstream targets Hey1 and Hey2, and vGPCR expression induced Notch2, Notch3, and Jagged1.122 Importantly, Notch3 is typically seen on mural or smooth muscle cells adjacent to endothelial cells but not in endothelial cells themselves.123 Induction of Notch3 suggests that KSHV induces a change in phenotype from differentiated endothelial cells. This is further supported by the observation that activation of the Notch-induced transcription factors Slug and zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 after KSHV infection contributes to the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) that is important for the malignant progression of infected endothelial cells independently from TGF-beta signaling,124 which regulates EndMT in non-malignant ECs.125 In vitro Notch inhibition with gamma-secretase inhibitors in KS-like cell lines induces mitotic catastrophe,126 suggesting that targeting Notch may be effective for KS. KSHV GPCR also stimulates MAPK signaling. Inhibition of the MAPK pathway in in vitro models of KS led to substantial reductions in the KSHV mediated induction of Notch pathway components, suggesting that MAPK signaling is the primary mechanism by which vGPCR induces Notch activation.122

In spite of the evidence showing the role of Notch and MAPK signaling in KS, the most clinical success to date has been by targeting the mTOR signaling. vGPCR directly leads to the overactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway that is necessary for KSHV-induced transformation of endothelial cells to KS spindle cells.115, 127 In addition, vGPCR activation of MTORC1 leads to secretion of pro-angiogenic factors causing paracrine signaling, which recruits and stimulates other non KSHV infected cells.127 As a result, mTOR inhibition has been used more successfully in the clinic for KS. Among kidney transplant patients with KS as a result of prolonged immunosuppression with cyclosporine, changing the drug to sirolimus resulted in rapid regression of all cutaneous KS lesions.128 Furthermore, long-term stabilization with mTOR inhibition was also seen in AIDS-related KS,129 demonstrating the importance of pathogenic KSHV viral signaling even in co-infected patients.

Human immunodeficiency virus

Overexpression of fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in normal endothelial cells results in vascular tumors in mice.130 In endothelial cell cancers, FGF signaling plays the largest role in KS. Synergy between the HIV-1 Tat protein and bFGF promotes the development of an angiogenic malignant phenotype in a preclinical mouse model.131 Targeting bFGF with antisense oligonucleotides inhibits the growth of AIDS-KS cells in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that targeting bFGF is a potential therapeutic strategy for KS.132 Tat works by several mechanisms, including binding to alpha-5-beta-1 and alpha-v-beta-3 integrin receptors via its RGD domain and stimulating migration and invasion, and also stimulating the release of preformed, extracellularly bound bFGF into a soluble form that can induce vascular cell growth and prevent apoptosis.133–135 Tat can also directly bind to VEGFR2 and stimulate VEGFR2 signaling independent of VEGF-A.136 Downstream, Tat activates multiple growth promoting signaling pathways including MAPK and FAK.137

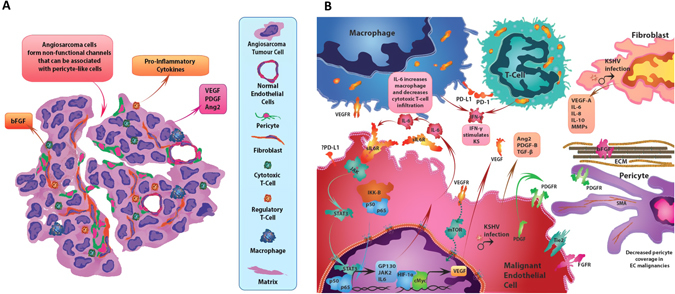

Microenvironment and intercellular interactions

The complex interplay between various components of the tumor microenvironment (e.g., immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells) can have either pro- or anti-tumor effects depending on the specific circumstances. Among patients with angiosarcoma, the presence of CD8 + tumor infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with a survival advantage.138 In addition to CD8 + cells, endothelial malignancies also have infiltration of CD3 + and CD4 + lymphocytes, as well as regulatory FoxP3 lymphocytes. In EHE, high CD3 + and FoxP3 + lymphocytes but not CD4 + or CD8 + lymphocytes were noted. All of the vascular tumors had high macrophage infiltration.139 Conflicting data exist regarding the expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1).139, 140

Macrophages, in particular tumor-associated macrophages, have long been known to have a pro-angiogenic effect that promotes tumor survival (reviewed in ref. 141). Macrophages are recruited to tumors by chemoattractants produced by tumor cells. A series of studies from Japan investigated the use of risedronate (to target macrophages) combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting with promising results.142, 143 High levels of Foxp3 + regulatory T-cells and CD163 + inhibitory macrophages relative to the number of cytotoxic T-cells were seen in these patients with primary angiosarcoma.143 In vitro treatment of angiosarcoma derived macrophages with docetaxel and risedronate increases the expression of C-X-C motif chemokines 10 and 11 (CXCL10 and CXCL11), both chemokines that recruit cytotoxic T-cells, in the treated macrophages.144 In a mouse model of angiosarcoma, inhibition of tumor-secreted IL-6 decreased macrophage numbers and increased cytotoxic T-cell infiltration, thereby decreasing tumor growth.145 This IL-6 secretion is dependent on an autocrine/paracrine network by which inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-KB) kinase subunit beta (IKK-beta) leads to IL-6 production and increased Stat3 activation by NF-KB-mediated transcription of gp130 and Janus kinase 2. In addition to the direct effect of IKK-beta on angiosarcoma cells, knockout of IKK-beta in host myeloid cells decreased neutrophil-derived nitric oxide, increased IL-4, and decreased IL-12 and interferon (IFN)-gamma, thus shifting the myeloid cells to the N2/M2 phenotype and increasing angiosarcoma growth.145 Moreover, inhibition of tumor secreted IL-8 has little effect on angiosarcoma cells in vitro, but prevents engraftment in vivo.146

In addition to the immunosuppression required for HHV8 infection, the immune microenvironment itself contributes to the malignant transformation of endothelial cells into KS. For example, normal endothelial cells cultured in media conditioned with activated T-cells have a phenotype consistent with early KS and are tumorigenic in nudemice.147 Both AIDS-associated and classical KS are infiltrated by CD8 + T-cells and CD14 + /CD68 + monocytes and macrophages that produce IFN-gamma.148 IFN-gamma induces KS spindle cells with an angiogenic phenotype that are similar to early KS cells. In contrast to findings in other tumors suggesting that high levels of infiltrating CD8 + lymphocytes are associated with improved outcomes, these lymphocytes have been proposed to contribute to the development of KS by producing IFN-gamma locally in the microenvironment.

Pericytes have long been known to communicate with endothelial cells to maintain EC stability. A minority of angiosarcomas develop pericyte coverage.149 Angiosarcomas that stain positive for alpha-smooth muscle actin (alpha-SMA), a pericyte marker, tend to have positive staining around malignant non-functional vascular channels.149, 150 In physiological vascular regulation, pericytes slow endothelial growth and their loss in other cancer types correlates with increased metastasis.151 In contrast, pericytes derived from less aggressive endothelial cell tumors contribute to the pro-angiogenic microenvironment by constitutive expression of VEGF-A and decreased Ang1 secretion152 (Fig. 3). Further studies are needed to clarify the role of the observed pericyte-like cells in high-grade endothelial malignancies.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of microenvironment in endothelial malignancies. a Tissue level schematic of angiosarcoma composed of malignant endothelial cells that form non-functional channel like structures. Stromal support cells such as fibroblasts and pericytes, and immune cells such as macrophages, cytotoxic and suppressor T-cells, and non-malignant endothelial cells all interact to promote tumorigenesis and angiogenesis in the microenvironment. b A selection of autocrine and paracrine signaling networks in the microenvironment of endothelial malignancies. Pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) is secreted by angiosarcoma cells and is dependent on JAK/STAT and IKK-beta signaling. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) is secreted by macrophages and cytotoxic T-cells, which stimulates Kaposi sarcoma (KS) tumor growth. Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) infection in resident fibroblasts stimulates secretion of multiple pro-angiogenic factors. Pericyte coverage is decreased compared to normal endothelium in endothelial malignancies, though the role of pericytes in directly promoting tumor growth is currently debatable. Ang2 angiopoietin2, b-FGF basic fibroblast growth factor, ECM extracellular matrix, FGFR fibroblast growth factor receptor,HIF-1alpha hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit, JAK tyrosine protein kinase, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, MMPs matrix metalloproteinases, MYC Myc proto-oncogene, PD1 programmed cell death protein 1, PDGF(R) platelet-derived growth factor (receptor), PDL1 programmed cell death 1 ligand, sIL6R soluble IL6 receptor, SMA smooth muscle actin, STAT signal transducer and activator of transcription, Tie2 TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial, VEGF(R) vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor)

Finally, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are activated stromal cells that have been shown to play a key role in promoting tumorigenesis in multiple cancer types. Interestingly, one of the primary mechanisms by which CAFs exert this effect is through VEGF153 and paracrine mediated crosstalk with endothelial cells.154 There is scant data regarding the role of fibroblasts specifically in endothelial cell malignancies, and the potential role of these cells needs to be investigated in angiosarcoma and hemangioendothelioma. The role of fibroblasts contributing to the paracrine growth signaling in KS is more established; latent infection of fibroblasts with KSHV leads the fibroblasts to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as VEGF-A, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, as well as matrix metalloproteinases that break down the extracellular matrix and increase tumor cell invasion,155, 156 and are required by KS spindle cells for in vitro growth and to maintain their tumorigenic potential in nude mice.157

Chromosomal rearrangements

Several chromosomal translocations are associated with vascular tumors (Table 1). Two separate translocations, both involving the Hippo pathway, were recently associated with EHE. The first, t(1;3), results in the fusion of the tafazzin gene TAZ (also known as WWTR1) and the calmodulin-binding transcriptional activator 1 gene CAMTA1.158–161 The second translocation results in the fusion of the yes-associated protein 1 gene YAP1 and the transcription factor binding to IGHM gene TFE3.162 YAP and TAZ are transcription factors involved in the Hippo pathway and, in normal cells, are involved in regulating cell size. The role of YAP and TAZ in cancer was reviewed recently.163 In endothelial cells, endoglin activation leads to YAP translocation to the nucleus and induction of extracellular matrix remodeling and secretion of pro-inflammatory chemokines.164 An additional translocation involves chromosomes 10p13 and 14q24; this specific translocation may involve placental growth factor (PlGF) and serve as a driver of EHE in some patients.165

The pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma subtype is also associated with a balanced chromosomal translocation, t(7;19)(q22;q13), which results in a fusion of the serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 1 gene SERPINE1 and FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B gene FOSB. This fusion is believed to lead to expression of the FOSB transcription factor under the SERPINE1 promoter.166 Although VEGFR1 is generally considered a decoy receptor that sequesters VEGF from VEGFR2, PlGF was previously shown to induce FOSB transcription via VEGFR1 independent from VEGFR2.167

Most studies that looked at angiosarcoma cytogenetics identified complex cytogenetics.12, 13, 168 Aberrations included gain or loss of entire chromosomes as well as partial chromosomes; interestingly, 2 of 8 cases in one series had duplication of the region on chromosome 4q that contains KIT and VEGFR2.12 A fusion of the Nucleoporin 160 kDa gene NUP160 and Solute Carrier Family 43, Member 3 gene SLC43A3, both on chromosome 11, was recently found in both primary angiosarcoma specimens and an established angiosarcoma cell line.169

Conclusions and future directions

Endothelial cell malignancies are characterized by dysregulation in multiple pathways that are highly regulated in endothelial cells for normal vascular development, as well as by some of the more typical oncogenic pathways found in other cancers. Aberrant activation of other regulatory pathways may explain why the majority of these tumors do not respond to VEGF-targeted therapies. Patient-derived cell lines and model systems that better replicate the biology seen in human angiosarcomas and hemangioendotheliomas are urgently needed to further our understanding of these rare tumors. The currently available genetically engineered mouse models of angiosarcoma are driven by knockout of Notch pathway components or FoxO,170 or overactivation of the mTOR pathway, but these may not reflect findings in human angiosarcomas. Canine models exist, but these are not practical for large scale in vivo research.

Future investigation should focus on mechanisms of adaptive resistance in those with initial responses to angiogenesis inhibitors. Understanding the mechanisms by which vascular tumors have primary or adaptive resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies can guide future research and treatment paradigms not only for malignancies of endothelial cell origin, but also for other cancers (e.g., ovarian,171 lung,172 and colon173). Future studies should also focus on rational drug combinations to block oncogenic pathways, as well as evaluating combinations of targeted therapy with conventional modalities such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The low incidence of these tumors limits the amount of tissue available for clinical and correlative research. Modified clinical trial designs and increased multi-institutional collaboration are needed to ensure sufficient sample sizes and to accelerate clinical studies of these rare tumors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joseph Munch, Kathryn Hale, and Katelyn Werner for editorial support and apologize to colleagues whose original work could not be cited due to space limitations. M.J.W. is supported by grants CCSG CA016672 and T32CA009666, and the Quad W-AACR Fellowship in Clinical/Translational Sarcoma Research. A.K.S. is supported by The Frank McGraw Memorial Chair in Cancer Research and the American Cancer Society Research Professor Award.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Van Zee KJ, Brennan MF, Maki RG. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer J. 2005;11:241–247. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200505000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravi V, Patel S. Vascular sarcomas. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2013;15:347–355. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonescu C. Malignant vascular tumors--an update. Mod. Pathol. 2014;27((Suppl 1)):S30–S38. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cioffi A, Reichert S, Antonescu CR, Maki RG. Angiosarcomas and other sarcomas of endothelial origin. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2013;27:975–988. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, Hughes D, Woll PJ. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu HS, Lee SS, Choi HS, Baek H, Koh JS. A case of pulmonary malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma by fine needle aspiration cytology. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2011;39:801–807. doi: 10.1002/dc.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo T, et al. Consistent MYC and FLT4 gene amplification in radiation-induced angiosarcoma but not in other radiation-associated atypical vascular lesions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:25–33. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biggar RJ, Chaturvedi AK, Goedert JJ, Engels EA, Study HACM. AIDS-related cancer and severity of immunosuppression in persons with AIDS. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:962–972. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin DM, et al. Part I: cancer in Indigenous Africans--burden, distribution, and trends. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:683–692. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70175-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itakura E, Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Detection and characterization of vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors in a series of angiosarcomas. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008;97:74–81. doi: 10.1002/jso.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonescu CR, et al. KDR activating mutations in human angiosarcomas are sensitive to specific kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7175–7179. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunze K, et al. A recurrent activating PLCG1 mutation in cardiac angiosarcomas increases apoptosis resistance and invasiveness of endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6173–6183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behjati S, et al. Recurrent PTPRB and PLCG1 mutations in angiosarcoma. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:376–379. doi: 10.1038/ng.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun SG, et al. Constitutive activation of mTORC1 in endothelial cells leads to the development and progression of lymphangiosarcoma through VEGF autocrine signaling. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:758–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornali E, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates angiogenesis and vascular permeability in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;149:1851–1869. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masood R, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is an autocrine growth factor for AIDS-Kaposi sarcoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stallone G, et al. ID2-VEGF-related pathways in the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma: a link disrupted by rapamycin. Am. J. Transplant. 2009;9:558–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bais C, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bais C, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor immortalizes human endothelial cells by activation of the VEGF receptor-2/ KDR. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:131–143. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theurillat JP, et al. Morphologic changes and altered gene expression in an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma during a ten-year course of disease. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2003;199:165–170. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emamaullee JA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: Implications for treatment and surgical management. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:191–197. doi: 10.1002/lt.21964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agulnik M, et al. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24:257–263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray-Coquard IL, et al. Paclitaxel given once per week with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a randomized Phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2797–2802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maki RG, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3133–3140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray-Coquard I, et al. Sorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II Trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO) Oncologist. 2012;17:260–266. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Mehren M, et al. Phase 2 Southwest oncology group-directed intergroup trial (S0505) of sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2012;118:770–776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomita H, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp successfully treated with pazopanib. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;70:e19–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miura H, Shirai H. Low-dose administration of oral pazopanib for the treatment of recurrent angiosarcoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2015;40:575–577. doi: 10.1111/ced.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva E, et al. Refractory angiosarcoma of the breast with VEGFR2 upregulation successfully treated with sunitinib. Breast J. 2015;21:205–207. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu HJ, et al. Refractory cutaneous angiosarcoma successfully treated with sunitinib. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013;169:204–206. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George S, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of sunitinib in the treatment of nongastrointestinal stromal tumor sarcomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3154–3160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Graaf WT, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bally O, et al. Eight years tumor control with pazopanib for a metastatic resistant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:12. doi: 10.1186/s13569-014-0018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trautmann K, Bethke A, Ehninger G, Folprecht G. Bevacizumab for recurrent hemangioendothelioma. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:153–154. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.498829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prochilo T, et al. Targeting VEGF-VEGFR pathway by sunitinib in peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, paraganglioma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: three case reports. Case Rep. Oncol. 2013;6:90–97. doi: 10.1159/000348429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uldrick TS, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma receiving antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:1476–1483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thurston G, Daly C. The complex role of angiopoietin-2 in the angiopoietin-tie signaling pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006550. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maisonpierre PC, et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan HT, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA, Parikh SM. Angiopoietin 2 is a partial agonist/antagonist of Tie2 signaling in the endothelium. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:2011–2022. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01472-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang H, Bhat A, Woodnutt G, Lappe R. Targeting the ANGPT-TIE2 pathway in malignancy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:575–585. doi: 10.1038/nrc2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, et al. Embryonic stem cell tumor model reveals role of vascular endothelial receptor tyrosine phosphatase in regulating Tie2 pathway in tumor angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:22399–22404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911189106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winderlich M, et al. VE-PTP controls blood vessel development by balancing Tie-2 activity. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:657–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amo Y, Masuzawa M, Hamada Y, Katsuoka K. Observations on angiopoietin 2 in patients with angiosarcoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004;150:1028–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buehler D, et al. Expression of angiopoietin-TIE system components in angiosarcoma. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:1032–1040. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown LF, Dezube BJ, Tognazzi K, Dvorak HF, Yancopoulos GD. Expression of Tie1, Tie2, and angiopoietins 1, 2, and 4 in Kaposi’s sarcoma and cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:2179–2183. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65088-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Angelo, S.P. et al. Alliance A091103 a phase II study of the angiopoietin 1 and 2 peptibody trebananib for the treatment of angiosarcoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 75, 629–638 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Hellstrom M, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;445:776–780. doi: 10.1038/nature05571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams CK, Li JL, Murga M, Harris AL, Tosato G. Up-regulation of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell function. Blood. 2006;107:931–939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benedito R, et al. The notch ligands Dll4 and Jagged1 have opposing effects on angiogenesis. Cell. 2009;137:1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan M, et al. Chronic DLL4 blockade induces vascular neoplasms. Nature. 2010;463:E6–E7. doi: 10.1038/nature08751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dill MT, et al. Disruption of NOTCH1 induces vascular remodeling, intussusceptive angiogenesis, and angiosarcomas in livers of mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:967–U464. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z, et al. Notch1 loss of heterozygosity causes vascular tumors and lethal hemorrhage in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:800–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI43114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tallquist M, Kazlauskas A. PDGF signaling in cells and mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kundra V, et al. Regulation of chemotaxis by the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta. Nature. 1994;367:474–476. doi: 10.1038/367474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickerson EB, et al. Imatinib and dasatinib inhibit hemangiosarcoma and implicate PDGFR-beta and Src in tumor growth. Transl. Oncol. 2013;6:158–168. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiesel H, Muller AM, Schmitt-Graeff A, Veelken H. Dramatic and durable efficacy of imatinib in an advanced angiosarcoma without detectable KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009;8:319–321. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.4.7547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chugh R, et al. Phase II multicenter trial of imatinib in 10 histologic subtypes of sarcoma using a bayesian hierarchical statistical model. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3148–3153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Reilly MS, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Reilly MS, et al. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277–285. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ye J, Li XF, Wang YD, Yuan Y. Long-term survival of a patient with scalp angiosarcoma and multiple metastases treated using combination therapy: a case report. Oncol. Lett. 2015;9:1725–1728. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Syed SP, Martin AM, Haupt HM, Arenas-Elliot CP, Brooks JJ. Angiostatin receptor annexin II in vascular tumors including angiosarcoma. Hum. Pathol. 2007;38:508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lannutti BJ, Gately ST, Quevedo ME, Soff GA, Paller AS. Human angiostatin inhibits murine hemangioendothelioma tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5277–5280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boye E, et al. Clonality and altered behavior of endothelial cells from hemangiomas. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:745–752. doi: 10.1172/JCI11432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan ZA, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells from infantile hemangioma and umbilical cord blood display unique cellular responses to endostatin. Blood. 2006;108:915–921. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller DW, et al. Elevated expression of endoglin, a component of the TGF-beta-receptor complex, correlates with proliferation of tumor endothelial cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;81:568–572. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990517)81:4<568::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong SH, Hamel L, Chevalier S, Philip A. Endoglin expression on human microvascular endothelial cells association with betaglycan and formation of higher order complexes with TGF-beta signalling receptors. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:5550–5560. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lebrin F, et al. Endoglin promotes endothelial cell proliferation and TGF-beta/ALK1 signal transduction. EMBO J. 2004;23:4018–4028. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blanco FJ, et al. S-endoglin expression is induced in senescent endothelial cells and contributes to vascular pathology. Circ. Res. 2008;103:1383–1392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McAllister KA, et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fritchie K, Attia S, Okuno S, Arndt C, Robinson S. Abstract B237: CD105: A therapeutic target for sarcomas. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013;12:B237. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.TARG-13-B237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hara H. Endoglin (CD105) and claudin-5 expression in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2012;34:779–782. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318252fc32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verbeke SL, et al. Active TGF-beta signaling and decreased expression of PTEN separates angiosarcoma of bone from its soft tissue counterpart. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:1211–1221. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Attia, S. et al. in CTOS (Salt Lake City, UT, 2015).

- 76.Nakayama M, et al. Spatial regulation of VEGF receptor endocytosis in angiogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:249–260. doi: 10.1038/ncb2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bai XC, et al. Phospholipase C-gamma1 is required for cell survival in oxidative stress by protein kinase C. Biochem. J. 2002;363:395–401. doi: 10.1042/bj3630395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Covassin LD, et al. A genetic screen for vascular mutants in zebrafish reveals dynamic roles for Vegf/Plcg1 signaling during artery development. Dev. Biol. 2009;329:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawson ND, Mugford JW, Diamond BA, Weinstein BM. Phospholipase C gamma-1 is required downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor during arterial development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1346–1351. doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liao HJ, et al. Absence of erythrogenesis and vasculogenesis in Plcg1-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9335–9341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. A single autophosphorylation site on KDR/Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-gamma and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:2768–2778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Poulin B, Sekiya F, Rhee SG. Intramolecular interaction between phosphorylated tyrosine-783 and the C-terminal Src homology 2 domain activates phospholipase C-gamma1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:4276–4281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409590102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bunney TD, et al. Structural and functional integration of the PLCgamma interaction domains critical for regulatory mechanisms and signaling deregulation. Structure. 2012;20:2062–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park JB, et al. Phospholipase signalling networks in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:782–792. doi: 10.1038/nrc3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kadamur G, Ross EM. Mammalian phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013;75:127–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prenen H, et al. Phospholipase C gamma 1 (PLCG1) R707Q mutation is counterselected under targeted therapy in a patient with hepatic angiosarcoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:36418–36425. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murali, R. et al. Targeted massively parallel sequencing of angiosarcomas reveals frequent activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway. Oncotarget6, 36041–36052 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Andersen NJ, Boguslawski EB, Kuk CY, Chambers CM, Duesbery NS. Combined inhibition of MEK and mTOR has a synergic effect on angiosarcoma tumorgrafts. Int. J. Oncol. 2015;47:71–80. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shiojima I, Walsh K. Role of Akt signaling in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2002;90:1243–1250. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000022200.71892.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Phung TL, et al. Akt1 and akt3 exert opposing roles in the regulation of vascular tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2015;75:40–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lahat G, et al. Angiosarcoma: clinical and molecular insights. Ann. Surg. 2010;251:1098–1106. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dbb75a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perry B, et al. AKT1 overexpression in endothelial cells leads to the development of cutaneous vascular malformations in vivo. Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:504–506. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Du W, et al. Vascular tumors have increased p70 S6-kinase activation and are inhibited by topical rapamycin. Lab. Invest. 2013;93:1115–1127. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leech JD, et al. A vascular model of tsc1 deficiency accelerates renal tumor formation with accompanying hemangiosarcomas. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015;13:548–555. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Italiano A, et al. Alterations of the p53 and PIK3CA/AKT/mTOR pathways in angiosarcomas: a pattern distinct from other sarcomas with complex genomics. Cancer. 2012;118:5878–5887. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manner J, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;176:34–39. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Verbeke SL, et al. Array CGH analysis identifies two distinct subgroups of primary angiosarcoma of bone. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015;54:72–81. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Styring E, et al. Key roles for MYC, KIT and RET signaling in secondary angiosarcomas. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;111:407–412. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kulkarni MV, Franklin DS. N-Myc is a downstream target of RET signaling and is required for transcriptional regulation of p18(Ink4c) by the transforming mutant RET(C634R) Mol. Oncol. 2011;5:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Italiano A, et al. The miR-17-92 cluster and its target THBS1 are differentially expressed in angiosarcomas dependent on MYC amplification. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:569–578. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rothweiler S, et al. Generation of a murine hepatic angiosarcoma cell line and reproducible mouse tumor model. Lab. Invest. 2015;95:351–362. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rodriguez-Diez E, et al. Cdk4 and Cdk6 cooperate in counteracting the INK4 family of inhibitors during murine leukemogenesis. Blood. 2014;124:2380–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-555292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu J, Martin HJ, Liao G, Hayward SD. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA protein stabilizes and activates c-Myc. J. Virol. 2007;81:10451–10459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li X, Chen S, Feng J, Deng H, Sun R. Myc is required for the maintenance of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. J. Virol. 2010;84:8945–8948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00244-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Delmore JE, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tolani B, Gopalakrishnan R, Punj V, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. Targeting Myc in KSHV-associated primary effusion lymphoma with BET bromodomain inhibitors. Oncogene. 2014;33:2928–2937. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dews M, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Knies-Bamforth UE, Fox SB, Poulsom R, Evan GI, Harris AL. c-Myc interacts with hypoxia to induce angiogenesis in vivo by a vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6563–6570. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ma W, et al. Hepatic vascular tumors, angiectasis in multiple organs, and impaired spermatogenesis in mice with conditional inactivation of the VHL gene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5320–5328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rathmell WK, Acs G, Simon MC, Vaughn DJ. HIF transcription factor expression and induction of hypoxic response genes in a retroperitoneal angiosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:167–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abedalthagafi M, et al. Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas generally lack hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 45 cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2010;14:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carroll PA, Kenerson HL, Yeung RS, Lagunoff M. Latent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of endothelial cells activates hypoxia-induced factors. J. Virol. 2006;80:10802–10812. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00673-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sodhi A, et al. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and secretion through mitogen-activated protein kinase and p38 pathways acting on hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4873–4880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jham BC, et al. Amplification of the angiogenic signal through the activation of the TSC/mTOR/HIF axis by the KSHV vGPCR in Kaposi’s sarcoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cai QL, Knight JS, Verma SC, Zald P, Robertson ES. EC5S ubiquitin complex is recruited by KSHV latent antigen LANA for degradation of the VHL and p53 tumor suppressors. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cai Q, Murakami M, Si H, Robertson ES. A potential alpha-helix motif in the amino terminus of LANA encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is critical for nuclear accumulation of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. J. Virol. 2007;81:10413–10423. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00611-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:707–719. doi: 10.1038/nrc2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]