Abstract

Singapore has an ageing population with a projected 53,000 people aged ≥ 60 years living with dementia by 2020. Primary care doctors have the opportunity to initiate early work-up for reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction, allowing identification of comorbidities and discussion of medical therapy options. Early diagnosis confers the sick role on the patient, which allays frustration and explains events and behaviour that may have strained relationships with family and friends. The patient can be encouraged to plan for future health and personal care options with a Lasting Power of Attorney and/or Advance Care Planning. Objective cognitive tests (e.g. abbreviated mental test and Mini-Mental State Examination) and brain imaging are adjuncts that help in formulating the diagnosis. Referral to a hospital memory clinic activates a multidisciplinary team approach to dementia, including clinical consultation, dementia counselling, physiotherapy sessions on gait/fall prevention, occupational therapy sessions on cognitive stimulation and caregiver training.

Keywords: cognitive impairment, dementia, memory clinic, neurocognitive disorder

Andre recently brought his 78-year-old grandfather to your clinic, as he was worried about his memory issues. Their neighbours had found his grandfather wandering around the neighbourhood and said he had trouble remembering what he needed to buy. He had also been complaining about Andre’s wife ‘not feeding him’. This had strained their family relationships.

WHAT IS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT?

Cognitive impairment is a decline in cognitive abilities, including memory, language and thinking skills. While forgetfulness is frequently observed in the process of normal ageing, some forms of cognitive impairment are recognisable as an early manifestation of dementia. The primary care physician is likely to be the only healthcare provider who has the opportunity to perform early identification and intervention. This article discusses our recommended approach to patients with cognitive impairment in primary care, especially patients who are getting forgetful; how to make the diagnosis of dementia; and when to refer them to a memory clinic.

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

Increased life expectancy and an ageing baby boomer population have resulted in an unprecedented increase in the number of elderly in Singapore. According to a local study by Chiam et al in 2003, the prevalence of elderly aged ≥ 75 years with dementia was 13.9%.(1) It was projected that by 2020, there will be 53,000 people aged ≥ 60 years living with dementia in Singapore.(2) In addition, the younger onset of chronic diseases and rising prevalence of obesity could be contributing to the rise in young-onset dementia. It is inevitable that healthcare staff will see more of both young (< 65 years of age) and elderly people with dementia in the near future. At the same time, sustained low birth rates have resulted in smaller nuclear families. These significant changes in our population demographics will likely result in a smaller ratio of working adult to dependants and higher public budgets dedicated to provision of healthcare and support for older people.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

People with cognitive impairment may continue to be undiagnosed in their own community for some time and may visit a primary care physician for other reasons, or while accompanying a family member to the clinic. These encounters allow the physicians to ask the correct questions and initiate the diagnostic process for dementia. The World Alzheimer Report 2011 listed interventions that are effective in the early stages of dementia and showed that there is a strong economic argument in favour of earlier diagnosis and timely intervention.(3) Patients who are diagnosed in the prodromal or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stages of Alzheimer’s disease can be encouraged to talk with their loved ones about their personal beliefs and goals of care and plan for their future health and personal care options.(4) A referral for a Lasting Power of Attorney and Advance Care Planning(5) can be arranged, if requested.

Fortunately, there is greater awareness of mental health and dementia today, with Health Promotion Board campaigns, mass media and social media. More people with mild memory complaints are consulting their doctors, unlike in the past, when their family members had to force them to see a doctor when they were already in a moderate or even advanced stage of dementia. Screening for dementia in a busy primary care practice can be done through simple cognitive tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The Memory Clinic at Changi General Hospital, a hospital memory clinic, has seen its attendance double from 177 to 390 new cases from 2014 to 2017, not including referrals for other geriatric issues with cognitive impairment.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

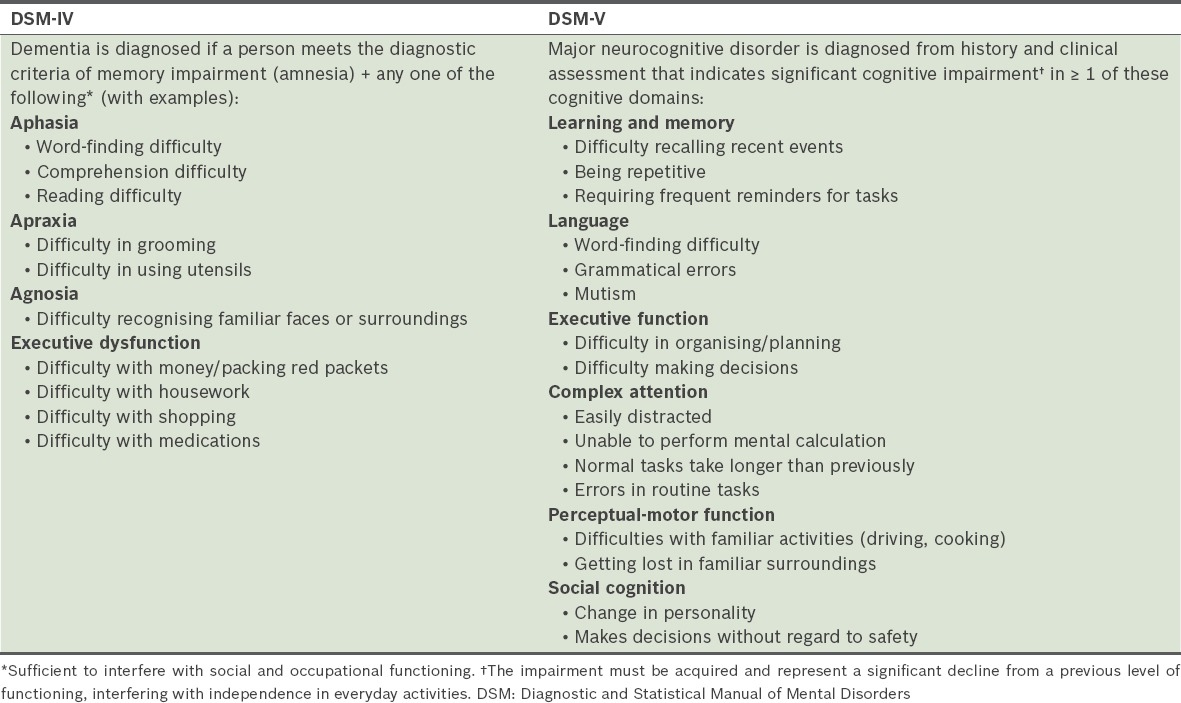

History-taking is still the most important aspect in identifying a patient with dementia or other cognitive impairment. In Table I, we have listed common questions that can be asked in each domain, such as repetitiveness in speech, misplacing objects and even wrongly accusing a domestic helper of stealing.

Table I.

Summary of common cognitive symptoms from the DSM-IV and DSM-V.

Patients may present with a history of losing their way in familiar environments (e.g. going home), being unable to follow simple instructions properly or having reduced safety awareness, resulting in increased risk of falls, home fires or personal security. They may present with a sudden change in chronic disease control if they had to administer medication themselves without any supervision. Other than problems with memory, patients with dementia may also be brought to the clinic by their spouses or family for new behavioural, functional and social issues that have increased the burden on their caregivers.

Possible causes of a patient’s forgetfulness include mild cognitive impairment, dementia, depression (i.e. pseudodementia), psychiatric illness and delirium. Before considering dementia or other cognitive impairment disorders, the clinician has to rule out reversible causes.(6) Forgetfulness or confusion that has a relatively short duration since onset (e.g. recent weeks to months) compels the physician to rule out delirium (i.e. a reversible, acute confusional state due to an underlying illness or disorder).(7) History of other major psychiatric illness or alcohol and substance abuse must also be excluded. If the forgetfulness is suspected to be due to a reversible cause, such as depression, the treatment for the cause should be administered. After the completion of a full therapeutic course, a review of cognition should then be repeated.

Dementia presents with a more chronic course and a progressive and irreversible clinical syndrome of cognitive decline that is severe enough to interfere with daily function. Many clinicians base their diagnosis of dementia on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV,(8) but the more recent DSM-V(9) has reorganised the cognitive domains and proposed new terminology (e.g. neurocognitive disorder).

Other than dementia, the other possible diagnosis of chronic forgetfulness is MCI (i.e. ‘minor neurocognitive disorder’ in the DSM-V) and depression (i.e. pseudodementia). An individual with MCI has only modest cognitive (usually memory) impairment and in most cases is still able to function independently, unlike in dementia.

In dementia, the short-term memory is affected before long-term memory. Therefore, a person with dementia may still have vivid memories of incidents that happened many years before, but be very poor in recalling recent events. A useful way of assessing a female homemaker’s executive function is to ask for specific details of how she prepares a particular dish, i.e. to ask her to describe the steps rather than asking her if she can cook. With her consent, her family members can be asked if her cooking quality had recently changed for the worse, or if there were reported incidents of accidentally burning food or pots in the kitchen. Other examples include packing a significantly different amount in red packets during Lunar New Year compared to previous years, or a previously good mahjong player suddenly being unable to play mahjong, unaware of having lost the game, or unable to remember her recent losses.

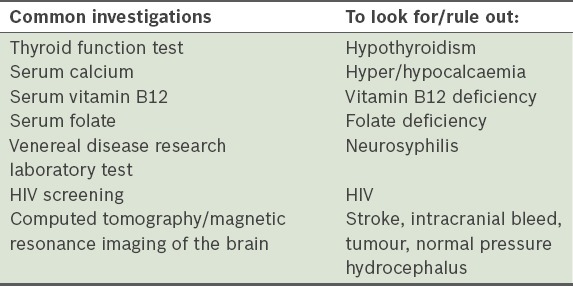

Medication review is useful to exclude cognitive impairment arising as side effects of chronic medications. Blood investigations are commonly requested to exclude hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, low vitamin B12 or folate levels, and also to exclude neurosyphilis and HIV for those with the relevant risk factors present (Table II).

Table II.

Common cognitive impairment laboratory investigations.

Diagnostic imaging studies that are commonly performed include computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, to exclude stroke, intracranial bleeding or a malignant lesion. It is important to highlight to the radiologist when brain metastases are suspected, as contrast-enhanced brain imaging may be needed.

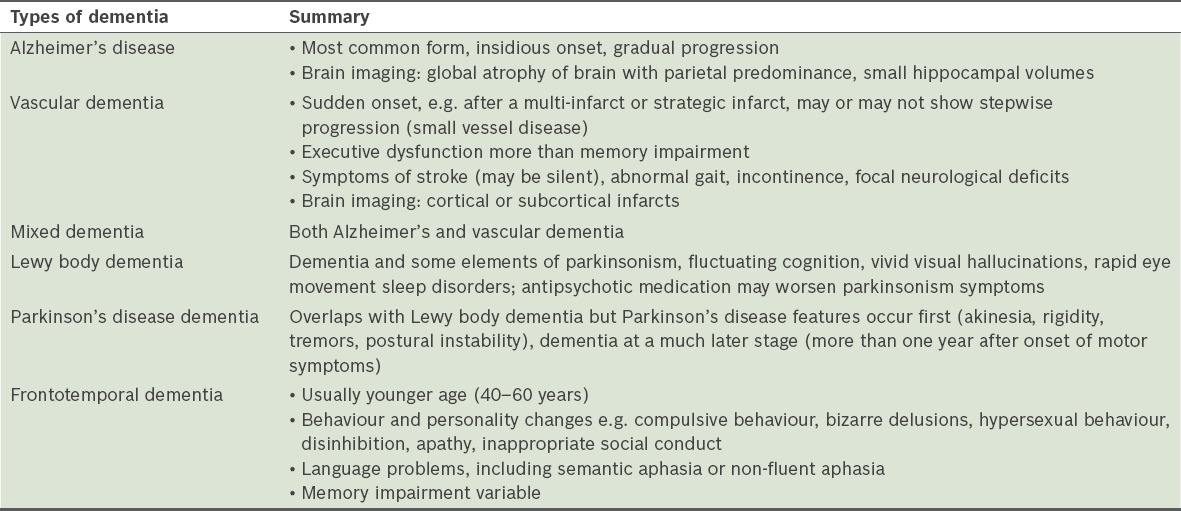

Objective cognitive tests such as the abbreviated mental test (AMT) or MMSE are common in the memory clinic as useful objective assessments and longitudinal monitoring tools. If MCI or mild dementia is suspected, the MoCA may be performed for highly educated patients to reduce the ceiling effects that are commonly encountered with the AMT or MMSE despite the patients’ impairment. Aside from cognitive test scores, clear documentation is required of any language barrier, uncooperativeness or low mood, hearing impairment, receptive/expressive dysphasia and possible effects of the highest attained education level, as these can affect the patient’s total score. Clinicians at the memory clinic may proceed with a referral to a psychologist for neuropsychology assessment if there is further doubt about the diagnosis (especially in MCI/mild dementia or younger patients who are more highly educated). Table III describes the common types of dementia.

Table III.

Common types of dementia.

USEFUL TIPS FOR CONSULTATION

It would be helpful if the patient is accompanied by a family caregiver who preferably stays with the patient during the assessment. An alternative is to obtain permission to speak to a family caregiver over the phone for a corroborative history.

Early identification of cognitive impairment allows underlying or reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction as well as comorbidities to be found, and early discussion of the options of medical therapy. Early diagnosis also confers the sick role on the patient, which can allay personal frustrations and/or provide an explanation for events and behaviour that might have strained relationships with family members and even close friends.

It is important to encourage the patient to talk about personal beliefs and goals of care with their loved ones and plan for their future health and personal care options. A referral for a Lasting Power of Attorney and Advance Care Planning can be arranged, if requested.

Referral to a memory clinic at a hospital allows for a multidisciplinary team approach to dementia and its associated comorbidities, such as poor physical function and neuropsychiatric symptoms. These may lead to high levels of dependency and morbidity, causing caregiver stress. The multidisciplinary team will have clinicians, dementia-trained nurses, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists (especially psychiatric occupational therapists) and psychologists to provide clinical consultation, dementia counselling, physiotherapy sessions on gait and fall prevention, occupational therapy sessions on cognitive stimulation and caregiver training.

Acknowledge and recognise the caregiver at every consultation. Helpful information about caregiver training, respite care and other sources of community support can be found on the Agency for Integrated Care’s Singapore Silver Pages website (https://www.silverpages.sg/).

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

A thorough assessment for dementia is important to exclude reversible causes.

The physician should routinely ask about depressive symptoms, as depression can mimic dementia and is treatable.

History-taking is a core part of assessment and should include the duration and onset of symptoms to rule out a more acute cause, e.g. delirium.

Objective cognitive tests (e.g. MMSE, AMT) and brain imaging are tools to help the clinician to formulate the diagnosis of dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease remains the most common form of dementia in both younger and older age groups.

Management of persons with dementia is complex and a multidisciplinary approach may be needed, e.g. referral to a memory clinic.

Persons with dementia who are deemed to have decision-making capacity (after clinical evaluation) are encouraged to consider discussing their preferences and making an advance care plan and a Lasting Power of Attorney.

Andre returned with his grandfather for his follow-up visit with you. After he was diagnosed with mild dementia at the initial visit, the grandfather had slowly come to accept his illness but still refused medication. The family had been rallying around him and was more understanding about his condition. You also took the opportunity to start Advance Care Planning conversations.

USEFUL LINKS

HealthHub, on recognising dementia: https://www.healthhub.sg/programmes/74/understanding-dementia

Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines on dementia 2013: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/healthprofessionalsportal/doctors/guidelines/cpg_medical/2013/cpgmed_dementia_revised.html

Alzheimer’s Disease Association Singapore: http://alz.org.sg

Office of the Public Guardian, on Lasting Power of Attorney: https://www.publicguardian.gov.sg

Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings, Module on Cognitive Impairment: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/Module_on_Cognitive_Impairment.pdf

Dementia Australia: https://www.dementia.org.au

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Yvonne Chan Hui Bin, Care and Health Integration, Changi General Hospital, Singapore, for her help in coordinating meetings and preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiam PC, Ng TP, Tan LL, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Singapore--results of the National Mental Health Survey of the Elderly 2003. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:S14–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer's Disease International and Alzheimer's Australia. Dementia in the Asia Pacific Region. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/adi/pdf/Dementia-Asia-Pacific-2014.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince M, Bryce R, Ferri C World Alzheimer Report. 2011:the benefits of early diagnosis and intervention. [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2011.pdf .

- 4.Leifer BP. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease:clinical and economic benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:S281–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.5153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.How CH, Koh LH. Not that way:Advance Care Planning. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:19–22. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings:module on cognitive impairment. [Accessed February 23, 2018]. Available at: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/professionals_preventive_older_pdf.html.

- 7.Chong MS, Sahadevan S. An evidence-based clinical approach to the diagnosis of dementia. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32:740–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.