Abstract

Background

The concept of feedback-seeking behaviour has been widely studied, but there is still a lack of understanding of this phenomenon, specifically in an Indonesian medical education setting. The aim of this research was to investigate medical students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in depth in one Indonesian medical school.

Methods

A qualitative method was employed to explore the feedback-seeking behaviour of undergraduate medical students in the Faculty of Medicine at Universitas Lampung. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with four student groups and each group consisted of 7–10 students from the years 2012, 2013 and 2014. Data triangulation was carried out through FGDs with teaching staff, and an interview with the Head of the Medical Education Unit.

Results

Study findings indicated that the motivation of students to seek feedback was underlain by the desire to obtain useful information and to control the impressions of others. Students will tend to seek feedback from someone to whom they have either a close relationship or whose credibility they value. The most common obstacle for students to seek feedback is the reluctance and fearfulness of receiving negative comments.

Conclusions

Through the identification of factors promoting and inhibiting feedback-seeking behaviour, medical education institutions are enabled to implement the appropriate and necessary measures to create a supportive feedback atmosphere in the learning process.

Keywords: constructive feedback, feedback, feedback-seeking behaviour, learning process, motivation

Introduction

Feedback plays an important role in the learning process since it affects motivation and students’ approaches towards the learning process (1, 2). Feedback provides information about student performance, what their strengths are and weaknesses that still can be improved. If given effectively, feedback can promote learning (3, 4). Receiving constructive feedback can raise learners’ awareness of their strengths, shine attention on areas that need more attention and contribute to making an action plan to improve these. Specific and immediate feedback on learners’ performance, coupled with an opportunity to improve, will help them to reach a pre-determined developmental stage. Feedback improves self-understanding and stimulates reflection, which is important to lifelong learning competencies. Good reflection needs constructive feedback and the presence of feedback will encourage the accuracy of self-reflection (2, 3).

Feedback provision is one of the psychological interventions widely used to promote the improvement of the learning process and personal behaviour, in which giving and seeking feedback are simultaneous activities (1, 2, 5). But the literature has demonstrated that students are put in a passive position, although each individual may, either intentionally or unintentionally, look for strategies to gather information about him- or herself for self-evaluation (5, 6). This particular strategy is defined as feedback-seeking behaviour (5, 7). This strategy is influenced by many factors, for example, a study has shown that female students and those with a high grade point average (GPA) are more active than other students in seeking feedback during the learning process (8).

Definition and Stages of Feedback-Seeking Behaviour

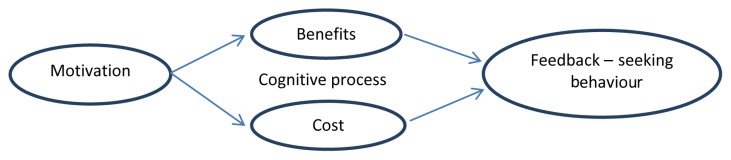

Ashford and Cummings (5, 9–11) define the feedback-seeking behaviour concept as a desire to attain information that is necessary to improving an individual’s self-concept and performance. Feedback-seeking behaviour may also be described as the ‘conscious devotion of effort toward determining the correctness and adequacy of behaviours for attaining valued end states’ (10: 93). When someone chooses to actively seek out feedback, at the same time, he or she considers the benefits and costs, and this becomes his or her motivation for seeking feedback. Therefore, as a process, feedback-seeking is considered to consist of three stages, which are motivation, cognitive process and behaviour (7).

Motivation stage

Based on their research, Ashford and Cummings describe three motivations underlying feedback-seeking behaviour, which are the desire for necessary information, to protect the ego and self-esteem from the threats of negative feedback and the need to control others’ impressions (12).

Cognitive process stage

During the cognitive process stage, individuals will consider the perceived value and cost of the feedback-seeking process (7). For example, there is a risk that the individual will be embarrassed when admitting anxiety and have his or her attention directed towards one’s one poorly perceived performance (11). In deciding whether or not to ask for feedback, there are three aspects to be considered. The first is effort cost, defined as the necessary effort to look for feedback. Next is face cost, which is the evaluative effect that one receives from others. The third aspect is inference cost or implications of inaccurate feedback interpretation (7). The perceptions regarding the benefits and costs of feedback comprise an important variable that influences feedback-seeking behaviour (10, 11).

Behaviour stage

After considering the benefits and costs of seeking feedback, an individual will then decide the most suitable method to look for feedback, whether it is inquiry or monitoring (5, 7).

The following diagram depicts the complete stages of the feedback-seeking process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stages in feedback-seeking process

Aspects Related to Feedback-Seeking Behaviour

Feedback-seeking behaviour is concerned not only with the stages within it but also the aspects that influence how feedback is looked for. There are five aspects related to feedback-seeking behaviour (9). First are the methods used to get feedback, inquiry or monitoring. Second is the frequency of the feedback-seeking process. Timing is also an aspect to be considered, for example an individual may look for feedback directly after an event or postpone it and this may depend on the individual’s mood. The fourth aspect consists of the characteristics of the target. Individuals will be more likely to obtain feedback from someone that they can easily access. Lastly is the topic that requires feedback (9, 13).

Based on the evidence suggested by previous studies, it is clear that the feedback-seeking process is a complex form of behaviour influenced by many external and internal factors. However, to our knowledge, research on the feedback-seeking behaviour of undergraduate medical students is still very limited. The research question of this study is: What are the perceptions of undergraduate medical students’ about feedback-seeking behaviour?

Methods

This study was conducted in an Indonesian medical school in one province on the island of Sumatra. The school has implemented a competency-based curriculum with a student-centred active learning approach. Students engage in problem-based learning discussions and also basic clinical skills sessions, in which students have opportunities to receive and give feedback. However, the undergraduate medical students’ behaviour in seeking feedback during the learning process remains unclear. A qualitative method was employed to allow in-depth exploration of the feedback-seeking behaviour of undergraduate medical students.

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out with 34 students and divided into four student groups. Each group consisted of 7–10 students for the years 2012, 2013 and 2014. A maximal variation sampling strategy was chosen, to ensure sample credibility and to include different participants with various backgrounds that might influence their perspectives on feedback. Each group was representative of students with a different gender, year of study, grade point average and place of origin. There was saturation after four FGDs. Probing questions for the FGDs and interviews were prepared based on key literature about the feedback process. The questions are related to the participants’ experiences in asking for and receiving feedback, including what they consider to be feedback, what they do to get feedback and how they respond to it. The principal investigator (DO) acted as the moderator in every focus group and the entire process was audio-recorded. An assistant to the moderator helped with note-taking, especially to record non-verbal language and back up the voice recorder. At the end of the focus group, the moderator summarised the discussion and asked for participants’ comments on the accuracy of the summary.

Data analysis has been conducted in line with data collection. Data were transcribed verbatim and a manual thematic analysis approach was utilised to identify emerging themes. Thematic analysis was started by reading all transcripts and making notes on the sentences in the transcript. Emerging themes were identified and a coding system was applied to the data. Then, data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing/verification, including member checking, followed the process. To improve the validity of the results, a triangulation was conducted through focus group discussions with five faculty members and an interview with the head of the Medical Education Unit (MEU). Ethical approval was given by the Faculty of Medicine University of Indonesia research ethics committee. All participants gave their written consent to participate in the study and the confidentiality of their identity is guaranteed.

Results

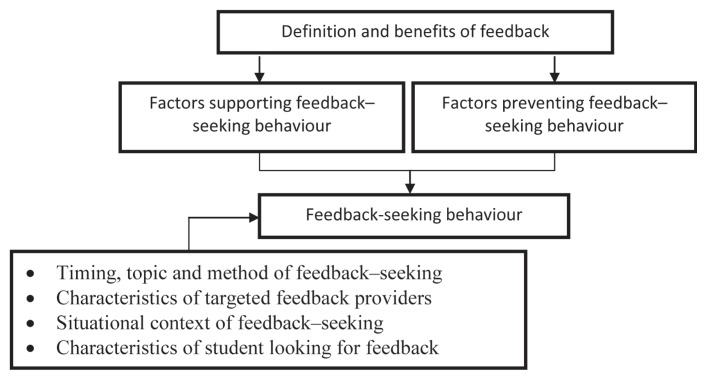

The thematic analysis revealed several themes related to feedback-seeking behaviour, as depicted in the diagram below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The relationship between themes identified from the data analysis

Students’ understanding of feedback can be categorised as general and specific. A general definition of feedback was the most significant theme that emerged from the analysis. Most students understand feedback as responses to what they have done, and it is aimed at improving their performance (Table 1). The complete description of students’ perceptions of the definition and benefits of feedback are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Students and teaching staff perceptions on the definition and benefits of feedback based on the comments identified from the thematic analysis

| Theme | Frequency of occurrence | |

|---|---|---|

| Students perceptions | ||

| 1 | General definition of feedback | |

| • Response to any problems in life | 4 | |

| • Feedback is the same as grumpy | 2 | |

| • Feedback is the same as evaluation | 3 | |

| • Feedback is a reaction to any given actions | 1 | |

| • Other people opinions on what has been done in order to improve the performance | 10 | |

| 2 | Specific definition of feedback | |

| • Two types of feedback: | ||

| (a) Active feedback: if there is a problem, they will actively seek feedback by asking. Active feedback can be divided into two types: | 4 | |

| – Positive feedback: constructive criticism and solution | ||

| – Negative feedback: criticism | ||

| (b) Passive feedback: if there is a problem, they do not seek help | ||

| • Source of feedback: | ||

| (a) From the self: the same as reflection | 7 | |

| (b) From the outside or external: from other people | ||

| • Any responses from the teaching staff related to the learning process | 1 | |

| Teaching staff perceptions | ||

| 3 | Response to what has been done by students in order to give the right concept to the students | 2 |

‘In my opinion, feedback is the same as a comment on what I did, … so we are able to improve ourselves in the future.’ (M3F4T3)

Students’ definitions of feedback were corroborated with faculty members’ perceptions on feedback, which were the responses to students’ actions aimed at guiding them. Based on the perceptions of the teaching staff, feedback is a response to the action of students, for the purposes of corroboration or guidance (Table 1).

‘What I do understand, giving responses on student actions, and the purposes are to corroborate or guide.’ (D1)

Factors that promote feedback-seeking behaviour, according to students’ perceptions, are described in Table 2. There were two factors that encourage students to look for feedback, namely the desire to obtain useful information and to control the impressions of others. The desire to look for the necessary information in order to enhance one’s own performance has become the primary motivation for seeking feedback.

Table 2.

Students perceptions on factors promoting feedback-seeking behaviour

| Theme | Frequency of occurrence | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Desire to get useful information: | |

| • Looking for information (policy changes, learning objectives, examination questions, how to learn, how to become a lecturer assistant, or about their self-weaknesses) | 25 | |

| • Comparing perceptions about the lessons that has been taught | 6 | |

| 2 | Desire to control impression from others: | |

| • Defensive impression: seeking for feedback in private area to avoid people judgement | 13 | |

| • Assertive impression: seeking for feedback from people who have close relationship that will give positive feedback | 5 |

Several factors prevent students from seeking feedback and these are listed in Table 3. Students rarely seek feedback from teaching staff because of reluctance, hesitation or fear of being discourteous.

Table 3.

Students perceptions on factors inhibiting feedback-seeking behaviour

| Theme | Frequency of occurrence | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Students’ self-perceptions | |

| • Fear of getting negative comments | 6 | |

| • Students have already realised their mistakes through self-reflection | 2 | |

| • Cultural factors: | ||

| – Afraid of showing the wrong attitude | 5 | |

| – Bashful, reluctant, feeling impolite | 15 | |

| • Personality: | ||

| – Trait: shy | 5 | |

| – The type that prefer to only receive feedback | 1 | |

| • Difficult to find a proper place and a right time | 6 | |

| 2 | Students’ perceptions about the teaching staff | |

| • Busy | 8 | |

| • Stern demeanor | 7 | |

| • Lecturers do not master the problem | 1 | |

| • Responses from the lecturers do not match expectations | 3 | |

| • There is a gap with the teaching staff | 7 |

‘I hesitate because lecturers are older, teachers may have different mindsets, we are afraid of our wrong behaviour.’ (M3F1T3)

Several students rarely looked for feedback from teaching staff because they were afraid of receiving negative comments about themselves.

‘Afraid of being scolded, yes it is your ability, why do you ask, if you do not pass means you are lacking in capabilities, … (M6F1T3)

Perceptions on teachers’ workload and characteristics also negatively affected student behaviour when looking for feedback.

‘It looks like each lecturer has no time, busy with their own business. So, when we have something to ask, we hesitate.’ (M6F2T2)

Based on the faculty’s perceptions, it was found that students were hesitant in looking for feedback because they were afraid of receiving negative comments, and felt distanced from the teaching staff. In addition, teachers also perceived that their daily workload and fierceness were also factors preventing students from soliciting feedback.

‘Maybe afraid, this lecturer already knew if I [student] am quite incapable. So they [student] are already afraid.’(D2)

Most students chose to ask for feedback from someone who was close to them and exhibited openness and good credibility.

‘… For me, generally, I prefer someone who is emotionally close. So, when someone is close with us, we already know who he/she is and he/she knows us.’ (M3F1T3)

Teachers perceived that the students who frequently look for feedback are those with outstanding performance and high motivation.

‘If someone is having a high motivation to study, he or she tends to be clever and active, … Someone who actively asks questions is smart, someone who is not smart tends to be perfunctory.’ (D1)

Students were more active in looking for feedback when being given tasks or punishments. Based on the teaching staff’s opinions, students sought feedback during problem-based learning tutorials, clinical skills sessions and in meetings with academic advisors. Meanwhile, based on the perceptions of the head of the Medical Education Unit, students actively looked for feedback only when the final score had been announced. Students tended to indirectly seek feedback, however they still asked questions related to their performance and achievement. When asking for feedback, they chose a private context to ensure privacy. However, there were also students asking for feedback publicly, for example within tutorial groups or clinical skills sessions.

Discussion

In the field of medical education, feedback is defined as ‘specific information about the comparison between a trainee’s observed performance and a standard, given with the intent to improve the trainee’s performance’. (14: p193) Through focus groups with students, different understandings about feedback have been identified. This finding may have resulted from the students’ incomprehension of feedback. Furthermore, most teachers still have not imparted the message to the students during teaching sessions that feedback consists of specific information about the students’ performance compared with a standard.

Incorrect comprehension about feedback can lead to a dysfunctional feedback process. This has become an inhibiting factor for feedback to be provided effectively. If students do not clearly understand the concept of feedback, then they will be reluctant in seeking feedback because they do not know the benefits. On the other hand, students that already have the proper understanding may hesitate in asking for feedback from the teaching staff when they realise that the staff is not capable of giving the constructive feedback. Students may also consider teachers’ resentment as a form of feedback, which may be the result of improper methods of giving feedback to students.

The absence of formal training regarding feedback can result in the teaching staff lacking the ability to provide specific and constructive feedback. Too frequently, the feedback provided is general and unhelpful. Although there are moments when teaching staff think that they have already given sufficient feedback, students still perceive the feedback-giving process as far from what they expected (15).

Someone with a desire to seek feedback will consider the benefits and costs of the feedback received. Students will look for feedback when they need information to enhance their performance, such as looking for learning objectives, examination questions, how to learn, how to become a lecturer’s assistant or about their self-weaknesses. Many researchers argue that this particular desire promotes feedback-seeking behaviour and is the main motivation for seeking feedback (12).

The most significant motivation for seeking feedback that emerged from the analysis is external motivation. An incorrect understanding of feedback may be the cause of the lack of intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation has more benefits in the feedback process since the drive to seek feedback comes from the recipient’s own awareness of the importance of feedback (16). A lack of intrinsic motivation can also result from students’ inabilities to assess their own performance (3, 16, 17). An under-developed ability to self-assess will prevent students from realising their own weaknesses since they are confident about themselves and have an accompanying reluctance to seek feedback. Therefore, students need to be equipped with self-assessment abilities through reflective activities in order to become reflexive students. The ability to conduct self-reflection has been argued in many examples of literature as one of the more important competencies that must be acquired as a doctor. Reflection can help doctors to realise their knowledge gaps and provide direction for self-development.

The analysis revealed that students are reluctant and hesitant to seek feedback from teachers. The reasons for this may include cultural factors and a medical education system that is hierarchical (5, 18, 19). Understanding the relationship and impact of culture on feedback-seeking behaviour is essential. In Indonesia, students are not used to asking questions because the learning system from primary to secondary level is still based upon a teacher-centred learning method, which tends to put learners in the role of a passive party. In a culture where asking questions of older people is not a common practice, individuals may avoid using direct inquiry because the evaluative costs may be too high (5).

Another finding is that students who are more active in looking for feedback are high-achievers and highly motivated students. Feedback-seeking behaviour is related to the skills of critical thinking, intellectual development and learning motivation (20). Students with well-developed critical thinking skills will be accustomed to self–assessment and will strive to enhance the quality of their learning (21). This critical thinking ability will then encourage students to actively seek feedback (20). Moreover, an increased sense of student motivation will promote feedback-seeking behaviour because such students have clear goal orientations (20). This finding is also supported by Sinclair and Cleland’s retrospective research on undergraduate medical students related to feedback-seeking behaviour following particular tasks and examination results (8). High-achiever students ask for feedback because they think feedback can help them to improve their future performance. On the other hand, low-achievers rarely look for feedback since they are fearful of receiving negative comments (12).

Apart from close relationships, students also consider the credibility of feedback providers. Teachers with high credibility are those with experience, outstanding achievement and capabilities on particular subjects. Competent and accessible feedback providers are influencing factors for feedback-seeking behaviour. This finding is related to the confidence in the validity of information received by students (9).

What this study adds to the literature is a deeper comprehension of the feedback process from the perspectives of students. This comprehension then leads to an appreciation of the necessity to equip medical students with the knowledge about feedback and skills needed to seek out and respond to feedback. Currently, most attention is given to medical teachers, however this study has put forward the problems found in students’ feedback-seeking behaviour, raising the possibility that a remediation process can be delivered through students’ training in the feedback process. Students should be able to look at feedback as something that is more than just comments from teachers, but rather as a critical part of the learning process and interconnected with motivation, critical thinking and self-assessment.

Conclusions

Despite the limited generalisation of the results, the study has provided important information regarding the behaviour of medical students in seeking feedback. The study has demonstrated that each stakeholder within the medical education has to be equipped with the proper knowledge and skills related to the feedback process. Teaching staff need to apply teaching strategies that can develop self-motivation in students for them to actively look for feedback during the learning process. Meanwhile, students require knowledge and skills related to the feedback-seeking process, which include the skills of self-reflection and critical thinking. Institutions also need to create a conducive atmosphere for students and teaching staff for a feedback-giving and -seeking process. Recommendations for further research are for studying with greater depth the cultural factors and hierarchical system of medical education, especially in Indonesia, and also conducting a larger scale of research that involves medical students from various medical schools regarding feedback-seeking behaviour in medical students, specifically in the clinical setting environment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Albert Scherpbier from Maastricht University for giving feedback and comment for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: DO

Analysis and interpretation of the data: DO, DS

Drafting of the article: DO

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: DS

Final approval of the article: DO, DS

Provision of study materials or patients: DO

Statistical expertise: DS

Obtaining of funding: DO

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: DO

Collection and assembly of data: DO

References

- 1.Murdoch-Eaton D, Sargeant J. Maturational differences in undergraduate medical students’ perceptions about feedback: maturation in feedback perception. Med Educ. 2012;46(7):711–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04291.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhury RR, Kalu G. Learning to give feedback in medical education. Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;6(4):243–7. https://doi.org/10.1576/toag.6.4.243.27023. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mubuuke AG, Louw AJN, Van Schalkwyk S. Utilizing students’ experiences and opinions of feedback during problem based learning tutorials to develop a facilitator feedback guide: an exploratory qualitative study. BMC Med Educ [Internet] 2016 Dec;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0507-y. [cited 2017 Oct 7] Available from http://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-015-0507-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Luque MFS, Sommer SM. The impact of culture on feedback-seeking behavior: an integrated model and propositions. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25(4):829–849. https://doi.org/10.2307/259209. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? an investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2009;84(7):910–917. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a858ad. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a858ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasman J. The feedback-seeking personality: big five and feedback-seeking behavior. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2010;17(1):18–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051809350895. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinclair HK, Cleland JA. Undergraduate medical students: who seeks formative feedback? Med Educ. 2007;41(6):580–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02768.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behaviour: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):232–241. doi: 10.1111/medu.12075. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.VandeWalle D, Ganesan S, Challagalla GN, Brown SP. An integrated model of feedback-seeking behavior: disposition, context, and cognition. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(6):996–1003. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.996. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VandeWalle D. A goal orientation model of feedback-seeking behavior. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2003;13(4):581–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2003.11.004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tayfur Ö. Antecedents of feedback seeking behaviors [Internet] Middle East Technical University; 2006. [cited 2014 Dec 10]. Available from http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/3/12607255/index.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashford SJ. Feedback-seeking in individual adaptation: a resources perspective. Acad Manage J. 1986;29(3):465–487. https://doi.org/10.2307/256219. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van De Ridder JMM, Stokking KM, McGaghie WC, Ten Cate OTJ. What is feedback in clinical education? Med Educ. 2008;42(2):189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brukner H. Giving effective feedback to medical students: a workshop for faculty and housestaff. Med Teach. 1999;21(2):161–165. doi: 10.1080/01421599979798. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330–1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1393. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballard B, Clanchy J. Study abroad: a manual for Asian students. Kuala Lumpur: Longman; 1984. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):787–791. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.684916. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.684916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang A, Ang S, Francesco AM. The silent chinese: the influence of face and enthusiasm on student feedback-seeking behaviors. J Manag Educ. 2002;26(1):70–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/105256290202600106. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul R, Willsen J, Binker AJA. Foundation for Critical Thinking. Critical thinking: how to prepare students for a rapidly changing world. Santa Rosa, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking; 1995. [Google Scholar]