Abstract

Background.

The Women’s Health Initiative has collected data on the aging process of postmenopausal women for over two decades, including data on many women who have achieved age 80 years and older. However, there has not been any previous effort to characterize the 80+ cohort and to identify associated retention factors.

Methods.

We include all women at baseline of the Women’s Health Initiative who would be at least 80 years of age as of September 17, 2012. We summarize retention rates during the study and across two re-enrollment campaigns as well as the demographic and health-related characteristics that predicted retention. Further, we describe the longitudinal change from baseline in the women identified as members of the 80+ cohort.

Results.

Retention rates were lower during each of two re-enrollment periods (74% and 83% retained during re-enrollment periods 1 and 2, respectively) than during the first and second data collection periods (90% each). Women who were retained were more likely to be white, educated, and healthier at baseline. Women age 80 and older saw modest changes in body mass index and depression burden, despite lower physical activity and increased cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions.

The characteristics of women who were retained in the 80+ cohort differ in significant ways compared with their peers at baseline. Identifying the characteristics associated with attrition in older cohorts is important because aging and worsening health has a negative impact on study attrition. Strategies should be implemented to improve retention rates among less healthy older adults.

Keywords: Aging, Women’s health initiative, Retention, Attrition, 80+ cohort

The United States is witnessing a rapid expansion of the proportion of the population greater than 80 years of age. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the proportion of the U.S. population 85 years and older has increased by 86% since 1980 ( 1 ), and the U.S. census bureau projects that the proportion 85+ will rise from 1.6% in 2011 to 4.5% by 2050. This is particularly important for the health of older women, as 61% of the U.S. population over 80 is female ( 2 ). The average life expectancy for a female born in 2010 is 81 years, and women age 75 have an additional 12.9 years of life expectancy ( 1 ). Research efforts focused on characterizing this segment of the population is important for our understanding of the aging process and identifying the particular health and social concerns of this group can better equip society to handle the impact of this demographic shift.

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) is a particularly valuable study for elucidating the impact of aging on women ( 3 ). Beginning in 1993, the study enrolled 68,132 postmenopausal women aged 50–79 for participation in four clinical trials: estrogen-alone hormone therapy versus placebo for women posthysterectomy at randomization; estrogen plus progestin versus placebo for women with intact uterus at randomization ( 4 ); low-fat dietary modification versus usual diet ( 5 ); and calcium and vitamin D versus placebo ( 6 ). Concurrently, a companion observational cohort study of 93,676 postmenopausal women of the same age range was recruited to develop a cohort in which other risk factors for chronic diseases could be evaluated ( 7 ). The WHI has yielded seminal findings in the areas of postmenopausal women’s health ( 8–14 ), and recent studies have addressed issues relevant to advanced age including cognition and memory ( 15 ), osteoporosis and hip fracture ( 16 ), and physical function ( 17 ), to name a few. The WHI contains one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of postmenopausal women aged 80 and older, with historical longitudinal data collected over 20 years in some cases, and this presents opportunities for research into the determinants of longevity and healthy aging. However, details of the cohort of WHI participants who have aged into their 80s and beyond has yet to be characterized.

An important component of characterizing a longitudinal cohort is the identification of factors associated with attrition, as these factors may bias study results. These include those related to lost follow-up and, for long-running studies such as the WHI, those related to differential re-enrollment across study phases. The WHI has had two re-enrollment periods; in an analysis within the WHI-HT trials these were associated with alterations in the cohort demographic and clinical characteristics ( 18 ). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to characterize the cohort of WHI participants who, based on their baseline ages, would potentially have been included among those aged 80+ as of September 2012. We aim to describe the group at baseline, to identify the characteristics that were associated with retention over time, and to describe the composition of the group of women who successfully contributed to the 80+ cohort, stratified by baseline age. Furthermore, among those who remained in the WHI beyond age 80, we describe the aging-related changes in health and demographic characteristics from baseline to their most recent assessment.

Methods

WHI Study Design

The design of the original WHI trials and cohort study have been described previously ( 3 ). The original clinical trials recruited 68,132 postmenopausal between 50 and 79 years of age to be randomized into studies exploring whether a low-fat dietary modification prevents breast and colorectal cancer incidence; conjugated equine estrogens, alone or in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate, prevent coronary heart disease; and whether calcium and vitamin D supplementation prevents hip fracture. Women could participate in one, two, or all three trials depending on eligibility. Participating women lived within proximity to 1 of 40 clinical centers throughout the United States. The observational study recruited 93,676 women from the same communities as the clinical trials to compare whether incidence of disease outcomes differed between the clinical trial participants and the community at large.

The estrogen plus progesterone clinical trial was terminated July 8, 2002, prior to the anticipated study completion date due to increased health risks observed in the active treatment arm ( 11 ). The estrogen-alone study was terminated early as well, on February 29, 2004, due to increased risk of stroke among the active treatment arm ( 9 ). However, both trials continued following participants after the termination of the active intervention until March 31, 2005, at which point the dietary modification and calcium plus vitamin D trials were also terminated as scheduled. All studies had an initial nonintervention posttrial extension phase through the end of 2010 that required renewed verbal consent prior to re-enrollment, and a second extension that required further consent occurred following the conclusion of the first. The second extension is currently scheduled to end in 2015.

Prospective members of the WHI 80+ cohort include all enrolled clinical trial and observational study participants whose age as of September 17, 2012, would be at least 80 years (regardless of survivorship, adherence, or lost follow-up). Women who ultimately are counted among the 80+ cohort must have consented into both extension studies and had at least one study visit, typically conducted via mail or telephone, after age 80.

Predictors of Attrition

Attrition in the WHI cohort for this article is defined as death, withdrawal, or non-re-enrollment in the extension studies prior to the age of 80. The characteristics used to predict attrition include the following variables as measured at baseline: age, education, smoking status, general self-reported health, depressive symptoms, total recreational physical activity, objectively measured body mass index (BMI), physical function, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) history. General self-reported health was measured as a Likert response of 1–5 where 1 indicates Excellent perceived health and 5 indicates Poor perceived health. Women were defined as having baseline depressive symptoms classified by a shortened Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D/DIS) score ≥0.06 ( 19 ). Physical function was measured using the self-reported physical function construct from the RAND SF-36 questionnaire ( 20 ). Prior CVD was defined as self-reported myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, revascularization, or congestive heart failure at baseline.

Statistical Analyses

The distribution of demographic and comorbid conditions of all women who would be eligible for inclusion in the 80+ cohort at baseline is summarized as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for discrete variables. Comparisons of re-enrollment eligibility proportions and observed reconsent rates among subgroups were compared using chi-square tests and means using one-way analyses of variance. Study attrition as a continuous function of time from randomization was summarized as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals using Cox proportional hazards models fitting separately for continuous age at baseline and discrete categorizations of race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, self-perceived health, depression, physical activity, BMI, and CVD history. Model-adjusted estimates of hazards of attrition were performed by fitting all predictors in a single model and reporting each model-adjusted hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval. A CONSORT diagram describes the sample sizes of the cohort at each phase and enumerates reasons for study attrition. Kaplan–Meier plots of attrition from enrollment date were presented for baseline age category (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75–79 years), physical activity (none, low, moderate, high), and BMI (<25, 25 to <30, 30 to <35, and 35 or greater kg/m 2 ).

Changes in health characteristics of women who have at least one assessment visit after attaining age 80 are presented as both unadjusted changes from baseline to most recent assessment, and adjusted means or odds ratio. Two groups are defined based on baseline age, such that women 70 or older at baseline attain eligibility earlier than women <70. Mean changes in continuous measures are estimated from a repeated measures mixed model, and odds ratios for categorical measures are estimated using generalized estimating equations. Both models adjust for age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, and education, and both models assume an unstructured covariance matrix.

This manuscript is primarily descriptive rather than inferential, although p values are included to compare rates of eligibility and re-enrollment. Most estimates are presented with confidence intervals to focus on estimation rather than inference. Given the large sample size, most comparisons achieve statistical significance, although clinical significance cannot be established through statistical tests alone.

Results

Change in Demographic Trends Over Time

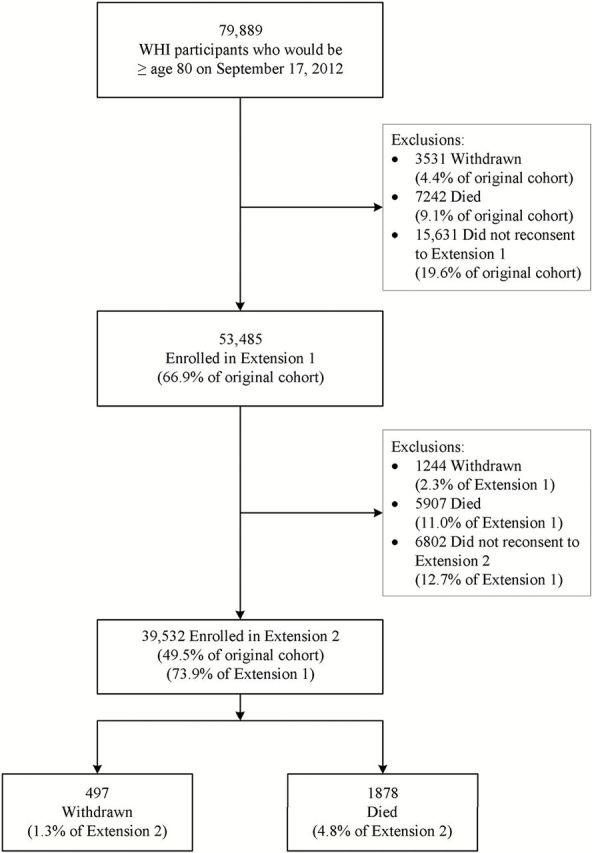

Table 1 describes the enrollment and retention data for all women who would be eligible for the 80+ cohort based on their baseline age. The first column describes the cohort at the time of study enrollment. The majority of women (60%) participated in the observational study with the dietary modification trial representing the largest proportion (26.7%) among the clinical trials. The mean age at baseline was 69.3 ( SD = 4.1) years, and broadly, the women tended to be predominantly white, well-educated, nonsmokers, and healthy, although most were overweight or obese. There were relatively low proportions of prior CVD and depression at baseline. Over 90% of the baseline group was eligible for enrollment in the first study extension. The characteristics that were most strongly associated with being ineligible for the extension include current smoking (81% eligible), fair or poor self-reported health (80.5% and 65.5%, respectively), and prior history of CVD (82.8%). Of those available for re-enrollment in the first extension, only 74.3% actually consented into the extension, with self-reported poor health (48.8%) and nonwhite race/ethnicity observing the highest rates of attrition. The proportion of the sample available for the second extension was comparable to the proportion available for the first extension, although the rate of enrollment in the second extension (82.6%) was notably higher than the first. The winnowing of older and lower functioning women results in a sample retained in the second extension dominated by women with lower baseline age and higher baseline function score compared with the overall baseline sample. The most common reason for study attrition listed in Figure 1 is failure to obtain consent for further participation during re-enrollment phases, followed by mortality and lastly participant withdrawal from study. However, re-enrollment rates improved dramatically for the second enrollment phase compared with the first (12.7% vs 19.6%, respectively), and 2,375 women who consented to the second extension died or withdrew prior to providing a visit after age 80.

Table 1.

Retention Rates of Women at Extension 1 and Extension 2, Overall and By Baseline Characteristics

| Enrolled in WHI, N (% of total) | Eligible for Extension 1, N (% of enrolled), p Value* | Consented Into Extension 1, N (% of eligible), p Value † | Eligible for Extension 2, N (% of enrolled in Extension 1), p Value ‡ | Consented Into Extension 2, N (% of eligible), p Value § | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 79,889 (100.0) | 72,013 (90.1) | 53,485 (74.3) | 47,842 (89.5) | 39,532 (82.6) |

| Enrolled in OS | 48,285 (60.4) | 43,355 (89.8) | 30,361 (70.0) | 27,148 (89.4) | 22,737 (83.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .7823 | p < .0001 | ||

| Enrolled trial at baseline | |||||

| HT: E alone | 5,583 (7.0) | 4,957 (88.8) | 3,836 (77.4) | 3,376 (88.0) | 2,634 (78.0) |

| HT: E + P | 8,254 (10.3) | 7,486 (90.7) | 6,112 (81.7) | 5,404 (88.4) | 4,335 (80.2) |

| p = .0007 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| Dietary modification | 21,365 (26.7) | 19,445 (91.0) | 15,823 (81.4) | 14,278 (90.2) | 11,720 (82.1) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .0001 | p = .0398 | ||

| Calcium + vitamin D | 16,031 (20.1) | 14,894 (92.9) | 12,739 (85.5) | 11,445 (89.8) | 9,451 (82.6) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .0982 | p = .8643 | ||

| Age, mean ( SD ) | 69.3 (4.1) | 69.2 (4.1) | 68.9 (4.0) | 68.7 (3.9) | 68.5 (3.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| Education | |||||

| ≤ High school diploma/GED | 20,056 (25.3) | 17,825 (88.9) | 11,932 (66.9) | 10,607 (88.9) | 8,256 (77.8) |

| Post HS | 59,317 (74.7) | 53,730 (90.6) | 41,253 (76.8) | 36,965 (89.6) | 31,071 (84.1) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .0262 | p < .0001 | ||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 41,563 (52.8) | 38,208 (91.9) | 28,347 (74.2) | 25,801 (91.0) | 21,341 (82.7) |

| Past | 32,948 (41.9) | 29,385 (89.2) | 22,165 (75.4) | 19,625 (88.5) | 16,320 (83.2) |

| Current | 4,142 (5.3) | 3,355 (81.0) | 2,302 (68.6) | 1,840 (79.9) | 1,420 (77.2) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| General health | |||||

| Excellent | 11,536 (14.6) | 10,834 (93.9) | 8,913 (82.3) | 8,251 (92.6) | 7,257 (88.0) |

| Very good | 32,268 (40.7) | 29,833 (92.5) | 23,237 (77.9) | 21,152 (91.0) | 17,872 (84.5) |

| Good | 27,928 (35.2) | 24,800 (88.8) | 17,474 (70.5) | 15,256 (87.3) | 12,093 (79.3) |

| Fair | 7,023 (8.9) | 5,655 (80.5) | 3,354 (59.3) | 2,744 (81.8) | 1,963 (71.5) |

| Poor | 498 (0.6) | 326 (65.5) | 159 (48.8) | 125 (78.6) | 98 (78.4) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| Depressive symptoms || | 6,936 (9.0) | 6,049 (87.2) | 3,983 (65.9) | 3,498 (87.8) | 2,722 (77.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .0004 | p < .0001 | ||

| Total recreational physical activity | |||||

| None | 11,110 (14.6) | 9,657 (86.9) | 6,749 (69.9) | 5,873 (87.0) | 4,674 (79.6) |

| Low | 22,104 (29.0) | 19,694 (89.1) | 14,278 (72.5) | 12,631 (88.5) | 10,174 (80.6) |

| Moderate | 21,397 (28.1) | 19,538 (91.3) | 14,710 (75.3) | 13,230 (89.9) | 11,042 (83.5) |

| High | 21,545 (28.3) | 19,864 (92.2) | 15,280 (76.9) | 13,896 (90.9) | 11,830 (85.1) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | |||||

| <25 | 28,460 (35.9) | 25,735 (90.4) | 19,428 (75.5) | 17,453 (89.8) | 14,695 (84.2) |

| 25 to <30 | 28,698 (36.2) | 26,132 (91.1) | 19,589 (75.0) | 17,597 (89.8) | 14,577 (82.8) |

| 30 to <35 | 14,496 (18.3) | 12,964 (89.4) | 9,378 (72.3) | 8,334 (88.9) | 6,751 (81.0) |

| 35 to <40 | 5,233 (6.6) | 4,580 (87.5) | 3,302 (72.1) | 2,884 (87.3) | 2,287 (79.3) |

| ≥40 | 2,302 (2.9) | 1,985 (86.2) | 1,341 (67.6) | 1,173 (87.5) | 893 (76.1) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| History of CVD ¶ at baseline | 9,007 (11.3) | 7,460 (82.8) | 5,034 (67.5) | 4,140 (82.2) | 3,180 (76.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 68,817 (86.1) | 62,239 (90.4) | 47,779 (76.8) | 42,663 (89.3) | 35,710 (83.7) |

| Black | 5,611 (7.0) | 4,873 (86.9) | 2,883 (59.2) | 2,595 (90.0) | 1,881 (72.5) |

| Hispanic | 2,022 (2.5) | 1,834 (90.7) | 1,016 (55.4) | 930 (91.5) | 676 (72.7) |

| American Indian | 295 (0.4) | 253 (85.8) | 142 (56.1) | 127 (89.4) | 97 (76.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2,020 (2.5) | 1,802 (89.2) | 1,000 (55.5) | 916 (91.6) | 699 (76.3) |

| Unknown | 1,124 (1.4) | 1,012 (90.0) | 665 (65.7) | 611 (91.9) | 469 (76.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p = .0070 | p < .0001 | ||

| Physical functioning construct, mean ( SD ) | 77.8 (20.7) | 78.8 (20.0) | 80.3 (19.0) | 81.0 (18.5) | 82.0 (17.8) |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | ||

Notes: CES-D/DIS = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; CHF = congestive heart failure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; GED = General Educational Development; HS = high school; MI = myocardial infarction; OS = Observational Study; WHI = Women’s Health Initiative.

*Comparison of percentages eligible (nondeceased, nonwithdrawn) for Extension 1 among subgroups. Continuous measure p values compare baseline means across eligibility status categories.

† Comparison of Extension 1 reconsent (continued consent among eligible) percentages among subgroups. Continuous measure p values compare baseline means across enrollment status categories.

‡ Comparison of percentages eligible (nondeceased, nonwithdrawn, and re-enrolled during Extension 1) for Extension 2 among subgroups. Continuous measure p values compare baseline means across eligibility status categories.

§ Comparison of Extension 2 reconsent (continued consent among eligible) percentages among subgroups. Continuous measure p values compare baseline means across enrollment status categories.

‖ CES-D/DIS score ≥0.06.

¶ Defined as MI, stroke, angina, revascularization, or CHF at baseline.

Figure 1.

Attrition among the 80+ cohort.

Predictors of Attrition

Table 2 describes in more detail the factors associated with attrition. The column of unadjusted results quantifies the hazard ratio of each of the predictors relative to the respective referent subgroup. The column of model-adjusted estimates takes into account all baseline demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table 2 . All minority subgroups experienced higher attrition rates relative to whites, although many of the odds ratios are sharply attenuated when adjusted for other health and demographic characteristics. The strongest single predictor of study attrition is low self-rated health status (“good”, “fair”, and “poor”) from the unadjusted column and “fair” and “poor” perceived health status after model adjustment. Generally, model adjustment increases the hazard ratio for attrition among current and past smokers, while most other relationships are attenuated compared with the unadjusted results.

Table 2.

Predictors of Attrition Within the 80+ Cohort by Baseline Characteristics

| N = 79,889 | Unadjusted | Adjusted* |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Age (1-y increase) | 1.08 (1.08, 1.09) | 1.08 (1.08, 1.09) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 1.65 (1.60, 1.71) | 1.38 (1.33, 1.43) |

| Hispanic | 1.70 (1.61, 1.79) | 1.60 (1.51, 1.70) |

| American Indian | 1.75 (1.52, 2.00) | 1.52 (1.31, 1.76) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.64 (1.56, 1.73) | 1.65 (1.56, 1.75) |

| Unknown | 1.33 (1.24, 1.44) | 1.22 (1.12, 1.32) |

| Education | ||

| Post HS | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≤ High school diploma/GED | 1.35 (1.32, 1.38) | 1.20 (1.18, 1.23) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Past | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) | 1.14 (1.12, 1.17) |

| Current | 1.64 (1.58, 1.71) | 1.78 (1.71, 1.86) |

| General health | ||

| Excellent | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Very good | 1.29 (1.25, 1.33) | 1.20 (1.16, 1.25) |

| Good | 1.84 (1.78, 1.90) | 1.54 (1.48, 1.59) |

| Fair | 2.85 (2.74, 2.96) | 2.07 (1.98, 2.16) |

| Poor | 4.09 (3.69, 4.52) | 2.57 (2.31, 2.87) |

| Depressive symptoms † | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.38 (1.34, 1.43) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) |

| Total recreational physical activity | ||

| High | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.10 (1.07, 1.13) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) |

| Low | 1.29 (1.26, 1.32) | 1.08 (1.05, 1.11) |

| None | 1.45 (1.41, 1.50) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | ||

| <25 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25 to <30 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) |

| 30 to <35 | 1.15 (1.12, 1.18) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.08) |

| 35 to <40 | 1.25 (1.20, 1.29) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) |

| ≥40 | 1.45 (1.37, 1.53) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.30) |

| History of CVD ‡ | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.61 (1.56, 1.65) | 1.22 (1.19, 1.26) |

Notes: CES-D/DIS = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; CHF = congestive heart failure; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; GED = General Educational Development; HS = high school; MI = myocardial infarction.

*Estimates from a multivariable model that includes all listed variables.

† CES-D/DIS score ≥0.06.

‡ Defined as MI, stroke, angina, revascularization, or CHF.

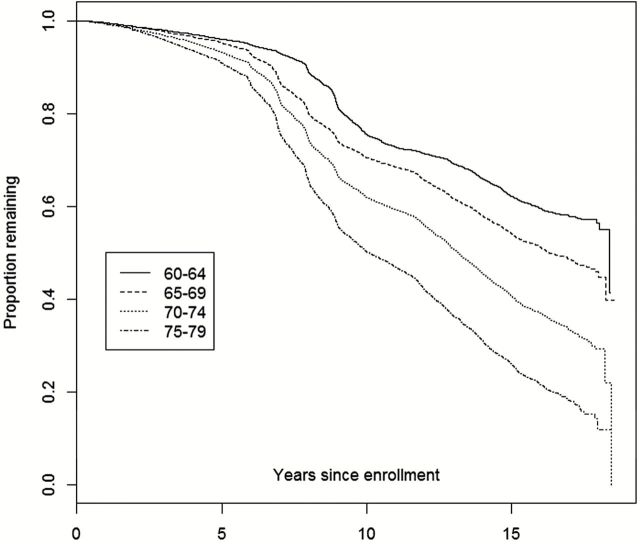

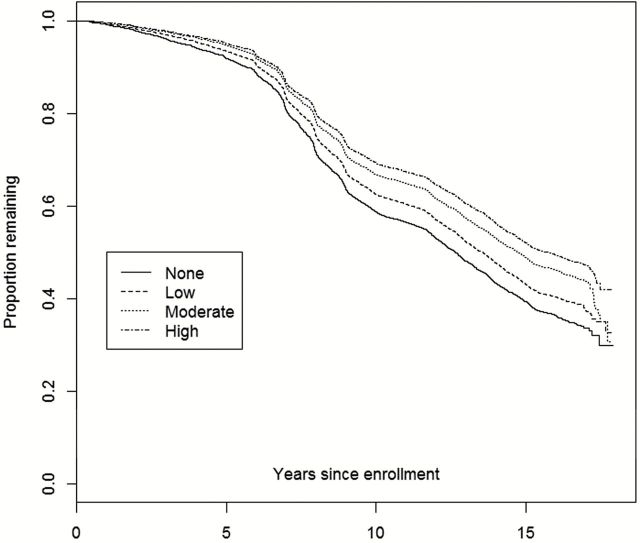

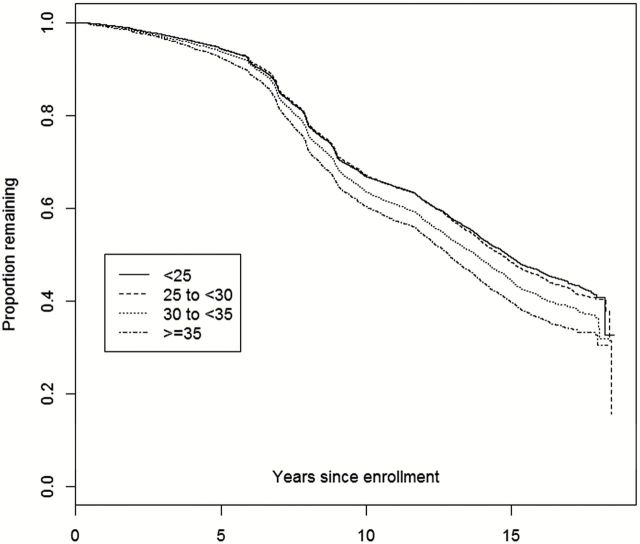

The relationship between age at enrollment and nonrenewal is further presented in Figure 2 , as we observe an accelerating downward trend among the older subgroups at approximately 7 years after baseline enrollment. Figure 3 displays a similar trend among baseline physical activity response, where less active participants have lower rates of retention and renewal. In Figure 4 , the lowest BMI categories (<25 and 25 to <30) are nearly identical, while the two highest BMI categories are incrementally associated with higher attrition.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of attrition from date of enrollment through September 17, 2012: By age at WHI enrollment. WHI = Women’s Health Initiative.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of attrition from date of enrollment through September 17, 2012: By baseline level of physical activity.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier plot of attrition from date of enrollment through September 17, 2012: By baseline BMI. BMI = body mass index.

Aging-Related Shifts Within Women Who Attain 80+ Years

Table 3 describes the aging-related changes in the 80+ cohort from baseline until the most recent assessment prior to September 17, 2012, stratified by baseline age group. Women younger than 70 at baseline reported slightly higher smoking rates, depression, overweight/obesity, and health status compared with women 70 and older, while older women have greater CVD. The unadjusted columns demonstrate that there were significant reductions in smoking and physical activity, worsened mean self-reported health status, and increases in CVD across both age categories over time; similarly, there were small increases in BMI in both baseline age groups and only slight increases in depressive symptoms among the older women. There were relatively minor shifts in depressive symptoms and BMI. The model-adjusted results largely reiterate these findings, in particular with decreases in self-reported health and increases in CVD over time.

Table 3.

Aging-Related Changes Within 80+ Cohort: Comparison of Physical, Mental, and Social States of 80+ Cohort From Baseline, by Baseline Age (limited to those in the current 80+ cohort), N = 35,188

| N | Unadjusted Results | Adjusted for Age at Enrollment, Race/Ethnicity, and Education* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Percent at Baseline | Mean/Percent at Most Recent Assessment | Change in Mean/ Percent From Baseline (95% CI) | Mean Change or Odds Ratio (95% CI) for Status at Follow-up Compared With Baseline | ||

| Smoking status: current smoker (%) | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | 18,681 | 3.8 | 1.5 | −2.3 (−2.5, −2.0) | 0.39 (0.35, 0.44) |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | 9,698 | 2.1 | 1.0 | −1.1 (−1.4, −0.8) | 0.46 (0.39, 0.56) |

| Self-reported health: | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | 21,819 | ||||

| a) Mean score † | 2.188 | 2.592 | 0.404 (0.392, 0.415) | 0.404 (0.393, 0.416) | |

| b) Fair/poor (%) | 4.7 | 12.8 | 8.0 (7.6, 8.5) | 2.99 (2.80, 3.19) | |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | 12,836 | ||||

| a) Mean score † | 2.254 | 2.743 | 0.489 (0.473, 0.504) | 0.489 (0.473, 0.505) | |

| b) Fair/poor (%) | 5.0 | 17.9 | 12.8 (12.2, 13.5) | 4.12 (3.80, 4.47) | |

| Depressive symptoms: | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | 17,580 | ||||

| a) Mean score | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.001 (−0.001, 0.003) | 0.001 (−0.001, 0.003) | |

| b) Symptoms present (score ≥0.06), % | 6.7 | 6.7 | −0.01(−0.51, 0.42) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | 8,952 | ||||

| a) Mean score | 0.02 | 0.023 | 0.004 (0.001, 0.006) | 0.004 (0.001, 0.006) | |

| b) Symptoms present (score ≥0.06), % | 5.5 | 6.3 | 0.79 (0.16, 1.43) | 1.15 (1.03, 1.29) | |

| Physical activity: number of episodes per week | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | 17,813 | 5.44 | 4.03 | −1.41 (−1.47, −1.35) | −1.41 (−1.48, −1.35) |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | 9,582 | 5.49 | 3.37 | −2.12 (−2.20, −2.03) | −2.12 (−2.21, −2.04) |

| BMI | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | |||||

| a) Mean | 20,455 | 27.37 | 27.61 | 0.24 (0.20, 0.27) | 0.24 (0.20, 0.28) |

| b) Overweight (≥30), % | 26 | 28 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.4) | 1.11 (1.09, 1.13) | |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | |||||

| a) Mean | 12,056 | 26.86 | 26.98 | 0.11 (0.06, 0.16) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.17) |

| b) Overweight (≥30), % | 21.8 | 22.9 | 1.0 (0.5, 1.5) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.09) | |

| CVD ‡ (%) | |||||

| < Age 70 at baseline | 22,105 | 6.9 | 17 | 10.1 (9.7, 10.5) | 2.78 (2.67, 2.90) |

| ≥ Age 70 at baseline | 13,084 | 9.5 | 22.2 | 12.6 (12.1, 13.2) | 2.72 (2.59, 2.85) |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; CHF = congestive heart failure; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; GED = General Educational Development; MI = myocardial infarction.

*Mean changes are estimated from a repeated measures, and odds ratios are estimated using generalized estimating equations, where both types of models assume an unstructured covariance matrix and adjust for linear age at enrollment, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, unknown), and education (≤ high school diploma/GED, post high school education).

† Score ranges from 1 to 5 where 1 = excellent and 5 = poor.

‡ CVD includes MI, revascularization, stroke, angina, CHF.

Discussion

These findings construct a consistent picture that women who remained in the study after their 80th birthday were generally healthier than their counterparts with respect to the health measures we observed. Generally, women who consent to participate beyond age 80 were younger, more active, more educated, and reported better general health. Conversely, we can identify the aspects of health that are most strongly associated with study attrition. Increased age is clearly identified as being a strong predictor of study attrition, although somewhat paradoxically, the re-enrollment rate for Extension 2 (beginning 2009–2010) among those available was higher than the re-enrollment rate for Extension 1 (beginning 2004–2005), despite the cohort having aged roughly 5 years. A potential explanation is that the second enrollment period was standardized through a centralized process, unlike the first enrollment period which was based on site-specific retention efforts. Furthermore, verbal consent was allowed by phone more widely for women interested in re-enrolling in Extension 2 compared with Extension 1. Negative health factors, particularly depressive symptoms, fair or poor self-rated health, smoking, sedentary activity, high BMI, and CVD were particularly strongly associated with attrition. Other strong social and demographic predictors of attrition include low educational attainment and nonwhite race/ethnicity. Given that these factors are also associated with many of the primary health outcomes of interest, re-enrollment should be made more attractive to individuals identified as unlikely to continue participation, particularly those with compromised or perceived compromised health.

The second portion of analyses focused on secular trends in health within the women who attained 80 years of age. Although the prevalence of smoking was low at baseline, these women demonstrated an ability to quit smoking, and BMI and depressive symptoms were largely unchanged from baseline. Furthermore, the passage of time yielded only modest shifts toward self-perceived worsened health and reduced physical activity. While the intention of this work is to characterize aging-related changes in both the composition of the cohort and the women themselves, the determinants of these women to preserve their health into late life should be further explored.

The winnowing of less health women could create some concern that the resulting 80+ cohort results in a sample of only the healthiest, most functional portion of the population. The effect of attrition, particularly during re-enrollment periods, appears to have a more dramatic influence on temporal changes in the cohort ( Table 1 ) than secular aging effects ( Table 3 ) in many respects. Such a cohort could make difficult future studies of rare diseases associated with aging, particularly if these diseases are more prevalent among women with long-term poor health. Conversely, these trends in attrition could create an 80+ cohort that is a valuable resource in the study of healthy aging among women, including identifying the factors that lead to improved outcomes and favorable study retention.

These findings are largely reflective of previous studies of factors of attrition among aging cohorts ( 21 , 22 ). However, the WHI obtained consent for additional data collection twice after the original enrollment, and re-enrollment periods have demonstrably high attrition rates. A similar study of WHI hormone therapy participants only found similar patterns and predictors of withdrawal ( 18 ); however, our retention rates are slightly lower, likely due to the advanced age and worsened health of our cohort. Although the recruitment and retention of minorities has substantially improved over the recent decades ( 23 ), our findings and others ( 18 , 24 , 25 ) indicate there remains much room to improve. There appears to be evidence that social support in particular could play a role in study retention ( 26 , 27 ), and the association between associated social support and healthy aging ( 28 , 29 ) could partially explain the relatively steady level of depression among the retained 80+ cohort. Importantly, future studies should explore recruitment strategies focused on enrolling participants at low-risk of attrition within subgroups with high dropout rates. Judging from the WHI experience, allowing phone consent for an aging population is a viable strategy to improve recruitment of aging participants, although clearly greater efforts for less healthy participants are still needed.

These findings are strengthened by the size and broad scope of the WHI, which allows for generalization to lifestyle and pharmacological intervention trials as well as large cohort studies. Furthermore, the long duration of the WHI provides important information about the aging process, as few large studies exist that have followed women from menopause into late life. However, the study is not without its weaknesses. Inclusion into the WHI required women to be generally healthy and high functioning, which may result in associations that do not reflect the population as a whole. Additionally, the present analysis aims to broadly characterize the shifts in the demographic characteristics of the WHI within the cohort of women who would be eligible to be 80 or older; such a limited scope is adequate for the present analysis, but the clinical significance of these associations cannot be reasonably explored in this work.

The WHI is an important resource for identifying the characteristics that predict longevity of women up to and beyond 80 years. We found that, at baseline, relatively healthy and educated women who predominantly identify as white had the highest chances of continuing participation in aging studies into late life. Further studies should explore in greater detail the determinants that lead to study attrition, particularly what are the key factors within lower health or minority subgroups that lead participants to voluntarily withdraw from research. Additionally, ongoing research studies should develop strategies to actively encourage women with actual or perceived health limitations, who are minority race/ethnicity, or who have lower educational attainment to continue participation to prevent underrepresentation of certain subgroups. Despite these differential forces, the WHI serves as one of the largest and most diverse aging studies available to the research community, and it will remain a key resource for the study of women aged 80 and above.

Funding

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN2682 01100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C.

References

- 1. National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care . Hyattsville, MD: ; 2013. . http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2012/001.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Census Bureau . The Older Population in the United States: 2011 . Washington, DC: ; 2013. . Table 1. http://www.census.gov/population/age/data/2011.html [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson GL, Cummings SR, Freedman LS, et al. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study . Control Clin Trials . 1998. ; 19 ( 1 ): 61 – 109 . doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR . The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants . Ann Epidemiol . 2003. ; 13 ( 9 suppl ): S78 – S86 . doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants . Ann Epidemiol . 2003. ; 13 ( 9 suppl ): S87 – S97 . doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson RD, Lacroix AZ, Cauley JA, Mcgowan J . The Women’s Health Initiative calcium-vitamin D trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants . Ann Epidemiol . 2003. ; 13 ( 9 suppl ): S98 – 106 . doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Langer RD, White E, Lewis CE, Kotchen JM, Hendrix SL, Trevisan M . The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures . Ann Epidemiol . 2003. ; 13 ( 9 suppl ): S107 – S121 . doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beresford SA, Johnson KC, Ritenbaugh C, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of colorectal cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial . JAMA . 2006. ; 295 : 643 – 654 . doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee . Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial . JAMA . 2004. ; 291 ( 14 ): 1701 – 1712 . 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howard B V, Van Horn L, Hsia J, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial . JAMA . 2006. ; 295 : 655 – 666 . doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000224659.41638.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. ; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators . Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial . JAMA . 2002. ; 288 ( 3 ): 321 – 333 . 10.1001/jama.288.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. ; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators . Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures . N Engl J Med . 2006. ; 354 : 669 – 683 . doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prentice RL, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial . JAMA . 2006. ; 295 : 629 – 642 . doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000224658.90363.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. ; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators . Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer . N Engl J Med . 2006. ; 354 : 684 – 696 . doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shumaker SA, Reboussin BA, Espeland MA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS): a trial of the effect of estrogen therapy in preventing and slowing the progression of dementia . Control Clin Trials . 1998. ; 19 ( 6 ): 604 – 621 . doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barbour KE, Boudreau R, Danielson ME, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of hip fracture: the Women’s Health Initiative . J Bone Miner Res . 2012. ; 27 ( 5 ): 1167 – 1176 . doi:10.1002/jbmr.1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seguin R, LaMonte M, Tinker LF, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical function decline in older women: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative . J Aging Res . 2012. ; 2012 : 10 . doi: 10.1155/2012/271589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Espeland MA, Pettinger M, Falkner KL, et al. Demographic and health factors associated with enrollment in posttrial studies: the Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy Trials . Clin Trials . 2013. ; 10 ( 3 ): 463 – 472 . doi:10.1177/1740774513477931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burnam MA, Wells KB, Leake B, Landsverk J . Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders . Med Care . 1988. ; 26 : 775 – 789 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection . Med Care . 1992. ; 30 : 473 – 483 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slymen DJ, Drew JA, Elder JP, Williams SJ . Determinants of non-compliance and attrition in the elderly . Int J Epidemiol . 1996. ; 25 ( 2 ): 411 – 419 . doi:10.1093/ije/25.2.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee C, Dobson AJ, Brown WJ, et al. Cohort Profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health . Int J Epidemiol . 2005. ; 34 ( 5 ): 987 – 991 . doi:10.1093/ije/dyi098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blumenthal DS, Sung J, Coates R, Williams J, Liff J . Recruitment and retention of subjects for a longitudinal cancer prevention study in an inner-city black community . Health Serv Res . 1995. ; 30 ( 1 Pt 2 ): 197 – 205 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK . Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants . Annu Rev Public Health . 2006. ; 27 : 1 – 28 . doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405. 102113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levkoff S, Sanchez H . Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the Centers on Minority Aging and Health Promotion . Gerontol . 2003. ; 43 ( 1 ): 18 – 26 . doi:10.1093/geront/43.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giles LC, Glonek GF V, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR . Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: the Australian longitudinal study of aging . J Epidemiol Community Heal . 2005. ; 59 ( 7 ): 574 – 579 . doi:10.1136/jech.2004.025429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powell DA, Furchtgott E, Henderson M, et al. Some determinants of attrition in prospective studies on aging . Exp Aging Res . 1990. ; 16 ( 1 ): 17 – 24 . doi:10.1080/03610739008253870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holahan CK, Holahan CJ . Self-efficacy, social support, and depression in aging: a longitudinal analysis . J Gerontol . 1987. ; 42 ( 1 ): 65 – 68 . doi:10.1093/geronj/42.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Penninx BWJH, van Tilburg T, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, Boeke AJP, van Eijk JTM . Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam . Am J Epidemiol . 1997. ; 146 ( 6 ): 510 – 519 . http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/146/6/510.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]