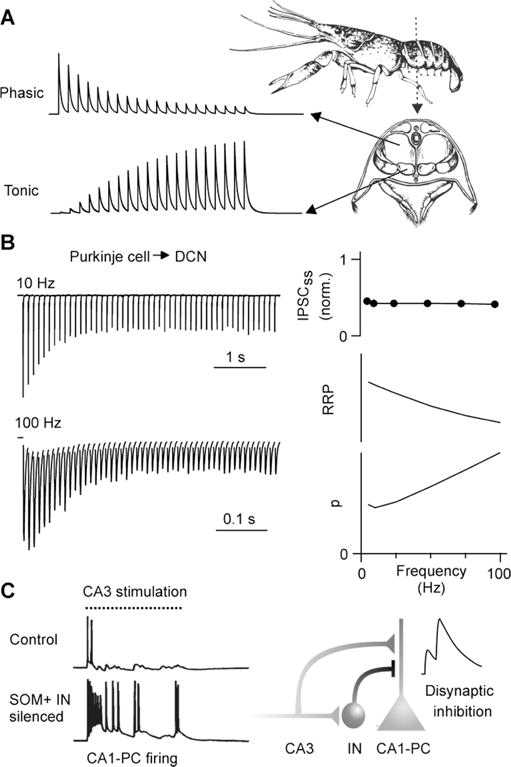

Figure 2. Functional consequences of facilitation.

A) Illustration of differential short-term plasticity of NMJs in crayfish abdominal muscles. Phasic NMJs produce large initial responses, but depress rapidly. Initial responses from tonic NMJs are small, but facilitate markedly as a function of firing frequency.

B) (Left) IPSCs recorded from a cerebellar nuclear neuron evoked by stimulating Purkinje cell axons at different frequencies. (Right) Average steady-state responses (top) are maintained at high frequencies because depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles (RRP, middle) is offset by frequency-dependent facilitation of p (bottom). The size of the RRP and p were predicted by a model fit to data. Adapted from Turecek et al. (2016).

C) (Left) Prolonged stimulation of Schaffer collaterals normally elicits only a short burst of activity with place-field characteristics, but when interneurons are pharmacogenetically silenced CA3 cells fire for the entire stimulus duration. Adapted from Lovett-Barron et al. (2012). (Right) Excitatory synapses from CA3 impinge on CA1 pyramidal cells (CA1-PC), as well as on SOM+ interneurons (IN) that inhibit CA1-PC dendrites. As CA3 inputs facilitate during the course of stimulation, IN firing gradually increases. This leads to a net facilitation of disynaptic inhibition that allows interneurons to shut down pyramidal cell activity late in the train. Adapted from Bartley and Dobrunz (2015).