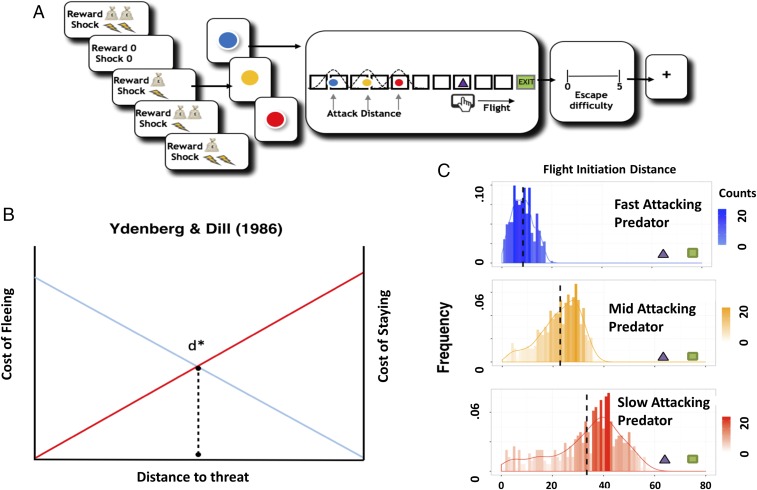

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedures, Ydenberg and Dill model (1), and distribution of escape decisions. (A) Subjects are told whether their decisions will result in high or low reward or shock. They are then presented with the image of the virtual predator where the color signals the attack distance (2 s) (e.g., blue, fast; red, slow). After a short interval, the virtual predator appears at the end of the runway and slowly moves toward the subject’s triangle. After an unspecified amount of time (e.g., 4–10 s), the artificial predator will attack the subject’s virtual triangle exit (i.e., attack distance). To escape, the subject must flee before the predator attacks. If the subject is caught, they will receive a tolerable, yet aversive, shock to the back of the hand. Trials end when the predator reaches the subject or the exit. To motivate longer fleeing time, the task will include an economic manipulation, where subjects will obtain more money the longer they stay in the starting position and lose money the earlier they enter the safety exit. After each trial, the subject is asked to report how difficult they found it to escape the virtual predator (4 s). (B) Modified schematic representation from the model proposed by Ydenberg and Dill (3). As the distance between the prey and the predator decreases, the cost of fleeing decays, while the cost of not fleeing rises. D* represents an optimal point where the prey should flee. (C) Histograms showing the distribution of subjects’ flight initiation decision (FID) choices for early-, mid-, and late-attacking predators, respectively. The x axis represents FID, while the y axis represents frequency of choice.