Significance

Blighted and vacant urban land is a widespread and potentially risky environmental condition encountered by millions of people every day. About 15% of the land in US cities is deemed vacant or abandoned, translating into an area roughly the size of Switzerland: over 3 million hectares of otherwise beneficial spaces remain neglected. Urban residents, especially in low-income neighborhoods, point to these spaces as primary threats to their health and safety. Cities continue to seek meaningful, evidence-based interventions for remediating vacant land. Standardized processes for the restoration of vacant urban land were experimentally tested on a citywide scale and found to significantly reduce gun violence, crime, and fear.

Keywords: epidemiology, ethnography, criminology, environment, human geography

Abstract

Vacant and blighted urban land is a widespread and potentially risky environmental condition encountered by millions of people on a daily basis. About 15% of the land in US cities is deemed vacant or abandoned, an area roughly the size of Switzerland. In a citywide cluster randomized controlled trial, we investigated the effects of standardized, reproducible interventions that restore vacant land on the commission of violence, crime, and the perceptions of fear and safety. Quantitative and ethnographic analyses were included in a mixed-methods approach to more fully test and explicate our findings. A total of 541 randomly sampled vacant lots were randomly assigned into treatment and control study arms; outcomes from police and 445 randomly sampled participants were analyzed over a 38-month study period. Participants living near treated vacant lots reported significantly reduced perceptions of crime (−36.8%, P < 0.05), vandalism (−39.3%, P < 0.05), and safety concerns when going outside their homes (−57.8%, P < 0.05), as well as significantly increased use of outside spaces for relaxing and socializing (75.7%, P < 0.01). Significant reductions in crime overall (−13.3%, P < 0.01), gun violence (−29.1%, P < 0.001), burglary (−21.9%, P < 0.001), and nuisances (−30.3%, P < 0.05) were also found after the treatment of vacant lots in neighborhoods below the poverty line. Blighted and vacant urban land affects people’s perceptions of safety, and their actual, physical safety. Restoration of this land can be an effective and scalable infrastructure intervention for gun violence, crime, and fear in urban neighborhoods.

Blighted and vacant urban land is a widespread environmental condition encountered by millions of people each day. About 15% of the land in US cities is deemed vacant or abandoned, translating into an area roughly the size of Switzerland: over 3 million hectares of otherwise beneficial spaces remain neglected (1, 2). Urban residents, especially in low-income neighborhoods, point to these spaces as primary threats to their health and safety (3).

Many cities have focused on complicated and expensive responses to their vacant land problem as part of large urban transformation initiatives (4). These responses have typically been intended to drive economic development and have often resulted in the relocation of residents, or the transformation of vacant spaces into luxury amenities or housing intended to economically buoy depopulating neighborhoods. While these strategies can change local economic conditions, they also can have the unintended consequence of displacing people who do not wish to move, create further entrenched neighborhood segregation (5), and may not adequately address the widespread problem of vacant land that chiefly affects low-resource neighborhoods.

The widespread vacant land problem in US cities calls for more than economic development or relocation programs. These solutions can be expensive, may benefit select groups of residents, and may not reflect residents’ needs and preferences. A recent, landmark randomized controlled trial demonstrated that individuals who relocated out of low-income urban residences via a voucher system had significant health and safety benefits. However, subsets of these individuals, such as adolescent boys, were also found to have been negatively affected by relocation and over half of the study’s participants who were given relocation vouchers opted not to use them (6, 7). This landmark study clearly indicates the importance of neighborhood context, although the high costs of relocation and the demonstrated preferences against moving suggest that perhaps less expensive, “in situ” approaches that can be applied to entire cities and allow residents to remain in their existing homes deserve consideration (4, 8).

In situ approaches, such as the inexpensive restoration of vacant urban land in residential neighborhoods, have been shown to affect economic outcomes (9). Such changes may also affect health and safety outcomes, such as violence and crime (10), although results have been mixed (11). On the one hand, low-lying trees, shrubs, and other vegetation on patches of urban land have been associated with greater fear of crime. Dense vegetation may decrease lines of sight and hide potential attackers and illegal activity (12–15) and has been associated with greater crime (13, 16–18). On the other hand, residents living near newly greened vacant lots, greened alleys, or in public housing with trees report enhanced feelings of personal safety (19–21) and other analyses link urban green space, street trees, and vegetation to lower levels of violence and crimes (18, 22–28).

Urban context matters in terms of human behavior. A contagion of problems can spread from blighted, dilapidated, and trash-strewn spaces to other nearby spaces, possibly leading to violence and crime (29–31). Vacant land restoration is a potential solution to these problems, yet mixed scientific findings suggest that controlled scientific testing of inexpensive, standardized, and reproducible interventions would be of value (10). To the best of our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial has tested such interventions on a citywide scale for a large representative urban sample that includes low-income residents.

We conducted a citywide cluster randomized controlled trial of standardized and reproducible in situ interventions to restore vacant land in a major US city and to test the effects of these interventions on violence, crime, and fear. The vacant land restoration interventions tested were specifically designed to be inexpensive, scalable, and sustainable changes to the basic lived environments that residents encounter on a daily basis. Interventions were done over a 2-mo period by teams of local landscape contractors.

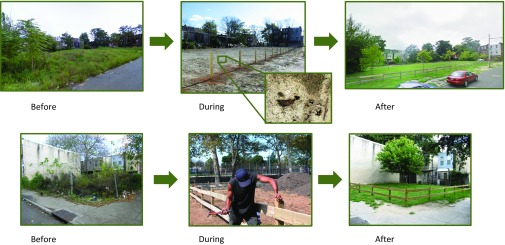

A “main intervention” involved the cleaning and greening of vacant lots across the city by removing trash and debris, grading the land, planting new grass using a hydroseeding method that can quickly cover large areas of land, planting a small number of trees to create a park-like setting, installing low wooden perimeter fences, and then regularly maintaining the newly treated lot throughout the postintervention period. The fencing was a visible sign that the lot was cared for and deterred illegal dumping, but was purposely low (about 1 m high) and included multiple ungated openings to encourage entry and use of the newly greened lot by residents. This intervention has been shown to be inexpensive and highly cost-effective (32), with initial costs averaging about $5 per square meter and maintenance averaging $0.50 per square meter thereafter (33). (Fig. 1 shows this process for two vacant lots that are similar to those in the study but for purposes of confidentiality are not actual study lots.) A second intervention involved only the cleaning of vacant lots on the same regular maintenance schedule throughout the postintervention period. This second intervention was examined in combination with the main intervention as an “any-intervention” treatment condition to test the effects of performing any activity over doing nothing.

Fig. 1.

Vacant land treatment process showing blighted preperiod conditions and postperiod restorations. The magnification (Upper Center) shows the grass seeding method used to rapidly complete the treatment process. Lots shown here are representative of those in the study, although for purposes of confidentiality are not actual study lots.

We tested the effects of these interventions on the commission of violence and crime, as well as perceptions of fear and safety among individual study participants, at a citywide level. To do this, 541 vacant lots from across the city were randomly sampled and then randomly assigned to intervention and no-intervention control conditions. Police-reported crime and nuisance outcomes, as well as outcomes from 445 randomly sampled nearby residents, were collected citywide and analyzed over a 3-y period before and after the study intervention period. We also incorporated a qualitative ethnographic component to document protocol fidelity and fully test, corroborate, and explicate ongoing hypotheses.

Results

Quantitative Findings.

Baseline balance was evident in terms of multiple variables at the participant level and the cluster level between the three intervention conditions (Table S1). All 110 vacant lot clusters, and 445 participants within their clusters, initially received the intended intervention to which they were randomly assigned. This formed the basis of an intent-to-treat analysis that was completed for all study outcomes. Despite their initial random assignment, select numbers of vacant lots did not maintain their originally assigned condition in the postperiod: some vacant lots that were randomly assigned to receive interventions deteriorated and some vacant lots that were randomly assigned to receive no intervention saw improvements in the postperiod (Fig. S1).

Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses demonstrated significant changes in participant-reported outcomes related to violence and fear for one’s safety. Participants in the main vacant lot intervention clusters experienced significantly reduced perceptions of crime (−36.8%, P < 0.05) and vandalism (−39.3%, P < 0.05) across all neighborhoods. This group also reported significantly reduced safety concerns related to going outside their homes (−57.8%, P < 0.05) and significantly increased use of outside spaces for relaxing and socializing (75.7%, P < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

ITT analysis of vacant land intervention effects on participant-reported outcomes

| Intervention variable | All neighborhoods | Neighborhoods below poverty line |

| Main intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| There is a lot of crime, % | −36.8 [−59.0, −3.0]* | −15.8 [−62.0, 88.0] |

| Too much drug use, % | −25.1 [−52.0, 16.0] | −18.0 [−64.0, 85.0] |

| Vandalism is common, % | −39.3 [−61.0, −6.0]* | 71.9 [−24.0, 288.0] |

| People watch out for each other, % | 12.1 [−28.0, 75.0] | 131.0 [0.1, 435.0]* |

| Not going out because of safety concerns, % | −57.8 [−82.0, −3.0]* | −70.9 [−93.0, 17.0] |

| Hanging out, relaxing, socializing outside, % | 75.7 [16.3, 163.2]** | 61.9 [−26.5, 257.1] |

| Any intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| There is a lot of crime, % | −35.4 [−56.0, −4.0]* | −17.0 [−59.0, 67.0] |

| Too much drug use, % | −29.9 [−53.0, 4.0] | −25.4 [−63.0, 51.0] |

| Vandalism is common, % | −29.1 [−53.0, 6.0] | 56.6 [−23.0, 217.0] |

| People watch out for each other, % | −12.7 [−42.0, 32.0] | 75.2 [−15.0, 263.0] |

| Not going out because of safety concerns, % | −35.5 [−69.0, 34.0] | −60.6 [−87.0, 24.0] |

| Hanging out, relaxing, socializing outside, % | 35.6 [−6.5, 96.1] | 29.0 [−34.6, 156.4] |

P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

ITT analyses also demonstrated significant changes in police-reported outcomes. Across all neighborhoods for the main vacant lot intervention, all crimes (−4.2%, P < 0.001), gun assaults (−2.7%, P < 0.05), and burglaries (−6.3%, P < 0.001) were significantly reduced after implementation. When considering any vacant lot intervention across all neighborhoods, all crimes (−3.1%, P < 0.001), gun assaults (−4.5%, P < 0.001), and burglaries (−3.9%, P < 0.001) were significantly reduced after implementation. In neighborhoods below the poverty line these effects were of similar statistical significance but more pronounced with reductions in all crimes (−4.7%, P < 0.001), gun assaults (−10.3%, P < 0.001), and burglaries (−7.9%, P < 0.001). Nuisances were significantly reduced after implementation of the main intervention across all neighborhoods (−12.8%, P < 0.01) and neighborhoods below the poverty line (−15.7%, P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

ITT analysis of vacant land intervention effects on police-reported outcomes

| Intervention variable | All neighborhoods | Neighborhoods below poverty line |

| Main intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| All crimes, % | −4.2 [−6.6, −1.8]*** | −4.7 [−7.8, −1.7]** |

| Gun assaults, % | −2.7 [−5.2, −0.2]* | −9.1 [−13.2, −5.0]*** |

| Robbery/theft, % | −1.1 [−2.5, 0.3] | 0.3 [−1.7, 2.3] |

| Burglary, % | −6.3 [−8.3, −4.4]*** | −7.7 [−10.6, −4.8]*** |

| Illicit drugs, % | 1.5 [−1.3, 4.3] | −0.3 [−4.8, 4.2] |

| Nuisances, % | −12.8 [−21.4, −4.2]** | −15.7 [−27.2, −4.3]** |

| Any intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| All crimes, % | −3.1 [−5.2, −1.0]*** | −4.7 [−7.5, −1.9]*** |

| Gun assaults, % | −4.5 [−6.7, −2.2]*** | −10.3 [−14.0, −6.6]*** |

| Robbery/theft, % | −1.0 [−2.2, 0.2] | 0.1 [−1.9, 1.8] |

| Burglary, % | −3.9 [−5.7, −2.1]*** | −7.9 [−10.5, −5.3]*** |

| Illicit drugs, % | −0.7 [−3.2, 1.9] | −1.8 [−6.1, 2.5] |

| Nuisances, % | −7.3 [−14.5, −0.1]* | −12.1 [−21.8, −2.4]* |

P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Contamination-adjusted ITT (CA-ITT) analyses of police-reported outcomes produced similar results to the ITT analyses (contamination and potentially inaccurate results can occur when participants in a randomized controlled trial do not adhere to their assigned treatment. A CA-ITT analysis uses the random assignment as an instrumental variable to adjust for noncompliance with the randomly assigned treatment). Across all neighborhoods, all crimes, gun assaults, and burglaries were found to be significantly reduced after implementation of the main and any vacant lot interventions (−9.2%, P < 0.01; −5.8%, P < 0.05; and −13.7%, P < 0.001). In neighborhoods below the poverty line, all crimes, gun assaults, and burglaries were also found to be significantly reduced after implementation of the main and any vacant lot interventions (−9.1%, P < 0.01; −17.4%, P < 0.001; and −14.6%, P < 0.001). These CA-ITT effects were largest, however, in neighborhoods below the poverty line that had experienced the implementation of any vacant lot intervention: all crimes (−13.3%, P < 0.01), gun assaults (−29.1%, P < 0.001), and burglaries (−21.9%, P < 0.001). Nuisances were also significantly reduced after implementation of vacant lot interventions ranging from −27.5% (P < 0.01) for implementation of the main intervention across all neighborhoods to −30.3% (P < 0.05) for implementation of any vacant lot intervention in neighborhoods below the poverty line (−28.1%, P < 0.05). All CA-ITT results had first-stage F-statistics >100.0 (Table 3).

Table 3.

CA-ITT analysis of vacant land intervention effects on police-reported outcomes

| Intervention variable | All neighborhoods | Neighborhoods below poverty line |

| Main intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| All crimes, % | −9.2 [−14.4, −4.0]** | −9.1 [−14.9, −3.2]** |

| Gun assaults, % | −5.8 [−11.3, −0.3]* | −17.4 [−25.3, −9.6]*** |

| Robbery/theft, % | −2.4 [−5.4, 0.5] | 0.6 [−3.2, 4.5] |

| Burglary, % | −13.7 [−18.0, −9.4]*** | −14.6 [−20.1, −9.1]*** |

| Illicit drugs, % | 3.4 [−2.8, 9.5] | −0.7 [−9.2, 7.9] |

| Nuisances, % | −27.5 [−46.3, −8.7]** | −28.1 [−49.5, −6.7]* |

| Any intervention vs. no intervention | ||

| All crimes, % | −8.7 [−14.6, −2.8]** | −13.3 [−21.2, −5.4]** |

| Gun assaults, % | −12.3 [−18.7, −6.0]*** | −29.1 [−39.7, −18.5]*** |

| Robbery/theft, % | −2.8 [−6.2, 0.5] | −0.1 [−5.2, 5.0] |

| Burglary, % | −10.7 [−15.7, −5.8]*** | −21.9 [−29.3, −14.6]*** |

| Illicit drugs, % | −1.9 [−8.9, 5.2] | −5.3 [−17.3, 6.8] |

| Nuisances, % | −18.1 [−38.0, 1.7] | −30.3 [−57.0, −3.7]* |

P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Displacement tests of the police-reported crime outcomes showed no significant spillover effects of the intervention. In none of the spatial scales studied was there a significant reduction in the central radius area around vacant lots that was coupled with significant increases in the ring surrounding this central area.

Ethnographic Findings.

To monitor the potential effects of the rise in property values that were occurring unevenly across the city during the years of the intervention, we initiated more detailed ethnographic case studies of reactions by neighbors to greening interventions in two microneighborhoods: one in an area subject to rapid economic development and one in a poorer area in which property values decreased during the first 2 y of the study and then stabilized.

The ethnographic team documented racialized tensions in the rapidly developing area that included hostility to greening by select residents. Ethnographers archived conflicts on social media that sometimes explicitly referenced vacant lot greening and community garden initiatives, but most frequently focused on city policies regulating row home renovations and property tax increases. They observed community hearings on community redevelopment held by local politicians who were disrupted by protesters from both sides of the divide. In contrast, in the more blighted and poorer area, virtually all residents interviewed were consistently positive about the greening of vacant lots. They also generally welcomed renovations and bemoaned the ongoing abandonment of decaying or undeveloped properties.

Open-air drug sales were visible in the ethnographically documented microneighborhoods and both suffered from high rates of crime and firearm violence. The poorer microneighborhood was more visibly impacted by drug trafficking, crime and gun violence, as well as by vacant properties. In both microneighborhoods, the team confirmed that drug sellers purposefully conducted business in front of vacant properties to reduce the likelihood of being “snitched on” (i.e., having the police called on them by neighbors) (34). In this poorer microneighborhood dominated by open-air illegal drug markets, residents routinely complained to the ethnographers that they did not dare confront drug sellers unless they were operating directly in front of the row home in which they lived. On multiple occasions, ethnographers observed drug sellers being shooed away from the front of occupied row homes by both their drug bosses and occupants. On these occasions, the sellers simply moved further down the block to resettle in front of a vacant property or lot and resumed sales.

Our ethnographic field notes contain multiple references to overgrown vacant lots providing concealment for routine drug use and escape routes during police raids. Larger lots with rubble and overgrowth often became open-air “shooting galleries,” where heroin and cocaine users sometimes congregated to buy syringes and inject behind bushes, discarded construction materials, or in the ruins of buildings. The criss-crossing informal pathways to shooting galleries through overgrown lots are visible in several of our field video footage and Google Street View images. Despite being located in one of the poorest areas in the city, drug sellers reported that they paid weekly rent to drug bosses (“bichotes”) for the right to sell on blocks where inhabited row homes were interspersed with vacant properties. Some of these blocks generated rents of $5,000 a week to their bichote “owners.”

Ethnographers also documented over a dozen gun battles for control of these inhabited, but blighted areas over a 7-y period that overlapped with the dates of this randomized controlled trial (35). Significantly, however, blocks that were too desolate and uninhabited appeared to render drug sellers excessively visible to the police and more subject to arrest on routine patrols. On several occasions the ethnographers observed police officers raiding vacant lots and buildings precisely because they noticed that individuals were congregated inside them.

Police officers and Philadelphia community members repeatedly reported that vacant lots were “storage lockers” for illegal firearms. However, youth in the poorer, drug-impacted microneighborhood reported that a gun was considered to be too valuable and risky to lose to be hidden far out of sight in a vacant lot behind overgrowth or mounds of garbage, lest it be found and used by the injection drug users who frequented vacant lots to hold up the nearest sales point. Instead, the ethnographers observed guns and drugs being carefully stored in secured locations that could be monitored easily from up to half a block away. The ethnographers documented weapons and drugs being “stashed” under couches in the apartments of trusted acquaintances on a block, inside car trunks, behind camouflaged car panels, wheel wells, muffler pipes, and under engine hoods. Significantly, these cars were then often purposefully parked in front of vacant lots or abandoned buildings. This gave them the advantage of remaining more clearly within the line of sight of drug sellers while simultaneously reducing the chance of a mandatory felony sentence for possession of a firearm in case of a police raid. The ethnographic team also documented a shooting incident that occurred over a stolen supply of drugs that, exceptionally, had been carelessly stored out of direct sight. Notably, the shooter had more carefully stored his firearm inside an apartment and walked back down the block to retrieve it to punish the suspected thief (36).

Discussion

We completed a citywide randomized controlled trial of actual place-based changes to urban spaces as a structural intervention to reduce violence and fear among residents. We enrolled a random sample of spaces and residents across a major US city and randomly assigned these spaces to receive interventions to restore blighted vacant land. These interventions significantly reduced gun violence and other police-reported problems, such as burglaries and nuisances. Randomly sampled residents who lived near newly renovated spaces also reported experiencing significantly less crime and vandalism, independently corroborating findings from police-reported data.

A statistically significant −58% reduction in people’s fear of going outside due to safety concerns and a 76% increase in their use of outside spaces are meaningful shifts that greatly extend the findings of prior quasiexperimental studies conducted at different times and in multiple cities such as Youngstown, Chicago, and Philadelphia (22, 26, 27). In addition, given a city like Philadelphia’s prior experience with gun violence (37), the −29% reduction found in this trial could translate into over 350 fewer shootings each year if the vacant land interventions tested here were scaled beyond just the locations of the study to the entire city.

These findings add experimental evidence to an emerging knowledge-base showing that cost-effective (32) structural interventions that are scalable to entire cities, like vacant land restoration, can have significant and lasting effects on seemingly intractable public safety issues such as gun violence and fear. Moreover, several of the beneficial effects found here were most pronounced in the poorest city neighborhoods, making these interventions useful to policymakers and planners attempting to reduce economic and quality-of-life disparities in effective, yet acceptable, ways for historically underresourced urban communities.

Urban violence leads to fear, even among residents not directly involved in the violence itself. Together, violence and fear can increase abandonment of previously vibrant city spaces and lead to a spiral of blight and decay in urban neighborhoods (38). As this experimental study has shown, direct changes to vacant urban spaces may hold great promise in directly breaking the urban cycle of violence, fear, and abandonment and doing so in a cost-effective way that has broad, citywide scalability (8).

Blighted vacant lots visibly signal that a neighborhood has not been attended to by the public and private sectors and that a physically decayed infrastructure has taken over creating unmanaged public space conducive to incivilities and crime that may be intimidating, demoralizing, or even have the effect of coopting some residents. As a result, unsafe behaviors, such as gun violence, can become sheltered and prevalent (3, 30). Such unsafe behaviors, although committed by a small number of individuals, are often street-based, occurring outside and in plain view for otherwise unconnected residents to witness and personally experience, despite not being actual victims of a crime or a shooting. These unsafe behaviors may even have audible cues, such as the sound of a firearm being discharged, extending their negative effects beyond simply what people see or the spaces within which they occur.

It follows that the abatement of vacant lots studied here generated enhanced perceptions of safety and reduced fear among neighborhood residents, encouraging them to spend time outside their homes and socialize with their neighbors. Our ethnographic data documented that unwanted and illegal activity that is often accompanied by gun violence, such as drug trafficking, is able to proceed more easily in front of vacant lots than it is in front of occupied residences. These data suggested that sellers and drug bosses even sometimes respected the right of neighbors to complain when sellers congregated directly in front of their homes. The positive effects of increases in face-to-face neighborly interaction are consistent with classic urban studies of “eyes on the street” and social capital as being effective mechanisms for crime reduction and neighborhood stabilization. This literature recognized the importance of sidewalk sociality, interactive social support, and placed-based “moral economies” of respect and solidarity in poor and working class neighborhoods (34, 39). The physical environmental shift of vacant lot restoration may have thus also led to a social environmental shift.

Ethnographic findings in the one poorer microneighborhood, where the poverty rate was about twice the citywide rate, are consistent with the greater magnitude of reductions in gun assaults, burglaries, and nuisances found in neighborhoods below the poverty line. Another mechanism behind the significant reductions in gun violence found here may be that vacant lots and the immediate perimeters around them create out-of-sight staging areas for illegal firearms until they are needed by individuals participating in illegal activity (3, 26, 40). Our ethnographic data showed that illegal firearms were hidden in cars that were then purposefully parked in front of vacant lots and buildings to avoid alienating neighbors who would object to such illegal activities directly in front of their homes.

The current cluster randomized controlled trial was undertaken as a new extension of prior studies limited by residual confounding and omitted variable biases. The study has also built in and directly tested concerns of spatial displacement, demonstrating that the reductions in violence found here were real reductions and not simply the relocation of violence “around the corner” (41). It has methodologically and analytically taken a large step forward, although some limitations remain.

One limitation is duration. The study assessed the effect of greening vacant lots over a reasonably long year-and-a-half follow-up period, although we cannot know what the impact of these interventions would be beyond the study period. However, prior quasiexperimental studies of the same vacant lot intervention found significant effects for some of the same outcomes, such as gun violence, that persisted for over 3.5 y on average (26).

Another concern is that, although both pre- and postintervention periods were 18-mo long and the preintervention period included three winter seasons and one summer season, while the postintervention period included two winter seasons and two summer seasons, our intervention period was driven by the choice of a spring planting season that specified by the landscape contractors as necessary and standard practice for successful land restoration. It is possible that the findings we report reflect underestimates given the greater occurrence of violence and crime during summer months. However, the seasonal imbalance between pre- and postperiods was equally experienced by both intervention and control groups given the random assignment, minimizing this effect.

An overarching concern is that the interventions implemented here, and any subsequent uses of this place-based intervention, may lead to gentrification and the unintended displacement of residents (42). This is possible, although prior analyses have found economic indicators, such as property taxes, to be unchanged and, if anything, reduced, after implementation of the greening interventions tested here (26). In addition, over the course of this study, local municipal legislation was also passed to limit property tax increases for longtime residents in curtailing displacement due to gentrification and only a very small percentage (<5%) of the vacant lots that were remediated using the intervention strategies described here have been developed into houses or commercial businesses (43; see also https://phsonline.org/programs/landcare-program). Thus, almost all of the vacant lots that were remediated remain open to residents for continued use and recreation. Our results also suggest that there are efficiencies for policymakers in focusing greening initiatives on the most infrastructurally distressed neighborhoods.

The vacant lot greening interventions studied here were not designed to lead to luxury housing developments or upscale, single-site recreational installations that would act as destination amenities to draw in nonresidents. They were explicitly chosen because they were inexpensive, scalable, and designed to be installed immediately proximal to lived space, oftentimes in low-income neighborhoods, to give local residents ready access to new, albeit basic amenities that they otherwise would not have had. Accompanying work has also found that newly greened vacant lots provide informal and accessible recreation space to nearby neighbors, based on evidence such as the accumulation of picnic tables, barbeques, toys, and recreational equipment (44).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that structural dilapidation and blight can be key causes of negative outcomes in terms of people’s safety, both their perceptions of safety and their actual, physical safety. When left untreated, vacant and blighted urban spaces contribute to increased violence and fear. The physical components of neglected and impoverished urban environments can be changed in inexpensive and sustainable ways as a direct treatment strategy for violence and fear in cities. Restoration of vacant spaces using well-delineated interventions, such as those shown here, is a scalable and politically acceptable strategy that can significantly and sustainably reduce persistent urban problems like gun violence.

The vacant land interventions shown effective here can be key in spurring people-focused urban connectivity and the reestablishment of vibrant, busy streets (39, 45). The effectiveness of infrastructural interventions in decreasing gun violence and crime and increasing perceptions of safety also offers a practical example of a public health approach that transcends the conventional model of targeting behavior change on the individual level. It suggests that macrolevel upstream approaches can have significant, positive population-level effects without conscious commitments by individuals to lifestyle changes. In the mid-19th century the disciplines of social medicine, public health, and epidemiology emerged out of the success of large public investments in interventions like sewage and potable water infrastructure, which curbed large-scale epidemics and transformed the health of entire cities (46). Infrastructural approaches to improving population health, such as those tested here, may again offer pragmatic, upstream strategies for addressing today’s complex urban challenges.

Materials and Methods

See SI Materials and Methods for a more detailed discussion of the materials and methods used. The study design was a controlled, parallel-group, cluster randomized trial that used a citywide random sampling procedure followed by stratified random assignment of eligible vacant lots into intervention and no-intervention arms in Philadelphia. All vacant lot interventions occurred over a 2-mo period, from April to May 2013, with an 18-mo baseline preperiod and an 18-mo follow-up postperiod. Observational ethnographic field notes were also collected two microneighborhoods following a previously tested protocol of direct, real-time participant-observation for randomized controlled trials. This trial was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (study ID ISRCTN92582209). Full and valid informed consent was obtained from all participants as reviewed and specified by both the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Los Angeles, Institutional Review Boards. All sections of this paper were written using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement for the reporting of cluster randomized trials. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals who were affiliated with this project and key to its success: Elorm Avakame, Paul Bailey, Rose Cheney, Akim Cooper, Hillary Cuesta, Jaime Fluehr, Mark Freker, Keith Gant, Sherry Glied, Keith Green, Robert Grossman, Laurie Kain Hart, Alisha Jordan, Amber Knee, Jeremy Levenson, Karriem Magnum, Deborah McColloch, Jamillah Millner, Charles Robinson, Patrick Spencer, Vicky Tam, Nicole Thomas, Alia Walker, Keahnan Washington, and Tali Ziv. This study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AA020331, R01DA010164, and R01DA037820 and Centers for Disease Control Grant R49CE002474.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1718503115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bowman AO, Pagano MA. Terra Incognita: Vacant Land and Urban Strategies. Georgetown Univ Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickerson C, Ebel R, Borchers A, Carriazo F. 2011. Major uses of land in the United States, 2007 (USDA Economic Research Service, Washington, DC), EIB-89.

- 3.Garvin E, Branas C, Keddem S, Sellman J, Cannuscio C. More than just an eyesore: Local insights and solutions on vacant land and urban health. J Urban Health. 2013;90:412–426. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9782-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Németh J, Langhorst J. Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land. Cities. 2014;40:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pritchett WE. The “public menace” of blight: Urban renewal and the private uses of eminent domain. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2003;21:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludwig J, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337:1505–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludwig J, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—A randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branas CC, Macdonald JM. A simple strategy to transform health, all over the place. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20:157–159. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wachter SM, Wong G. What is a tree worth? Green‐city strategies, signaling and housing prices. Real Estate Econ. 2008;36:213–239. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo MC, South EC, Branas CC. Nature-based strategies for improving urban health and safety. J Urban Health. 2015;92:800–814. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9983-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogar S, Beyer KM. Green space, violence, crime: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17:160–171. doi: 10.1177/1524838015576412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gobster PH, Westphal LM. The human dimensions of urban greenways: Planning for recreation and related experiences. Landsc Urban Plan. 2004;68:147–165. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasar JL, Jones KM. Landscapes of fear and stress. Environ Behav. 1997;29:291–323. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasar JL, et al. Proximate physical cues to fear of crime. Landsc Urban Plan. 1993;26:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo FE, Bacaicoa M, Sullivan WC. Transforming inner-city landscapes trees, sense of safety, and preference. Environ Behav. 1998;30:28–59. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher BS, Nasar JL. Fear of crime in relation to three exterior site features prospect, refuge, and escape. Environ Behav. 1992;24:35–65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michael SE, Hull RB, Zahm DL. Environmental factors influencing auto burglary: A case study. Environ Behav. 2001;33:368–388. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan GH, Prestemon JP. The effect of trees on crime in Portland. Environ Behav. 2012;44:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garvin EC, Cannuscio CC, Branas CC. Greening vacant lots to reduce violent crime: A randomised controlled trial. Inj Prev. 2013;19:198–203. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo FE, Sullivan WC, Coley RL, Brunson L. Fertile ground for community: Inner-city neighborhood common spaces. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:823–851. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang B, Mak CN, Larsen L, Zhong H. Minimizing the gender difference in perceived safety: Comparing the effects of urban back alley interventions. J Environ Psychol. 2017;51:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo FE, Sullivan WC. Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Environ Behav. 2001;33:343–367. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfe MK, Mennis J, Mennis J. Does vegetation encourage or suppress urban crime? Evidence from Philadelphia, PA. Landsc Urban Plan. 2012;108:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Troy A, et al. The relationship between tree canopy and crime rates across an urban–rural gradient in Baltimore. Landsc Urban Plan. 2012;106:262–270. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troy A, et al. The relationship between residential yard management and neighborhood crime. Landsc Urban Plan. 2016;147:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branas CC, et al. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondo M, Hohl B, Han S, Branas C. Effects of greening and community reuse of vacant lots on crime. Urban Stud. 2015;53:3279–3295. doi: 10.1177/0042098015608058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo MC, Low SC, Henning J, Branas CC. The impact of green stormwater infrastructure installation on surrounding health and safety. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e114–e121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L. The spreading of disorder. Science. 2008;322:1681–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.1161405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harcourt BE, Ludwig J. Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. Univ Chic Law Rev. 2006;73:271–320. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branas CC, et al. Urban blight remediation as a cost-beneficial solution to firearm violence. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:2158–2164. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonham JB, Smith PL. Transformation through greening. In: Birch EL, Wachter SM, editors. Growing Greener Cities. Penn Press; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karandinos G, Hart LK, Castrillo FM, Bourgois P. The moral economy of violence in the US inner city. Curr Anthropol. 2014;55:1–22. doi: 10.1086/674613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourgois P, Hart LK. Pax narcotica: Le marché de la drogue dans le ghetto portoricain de Philadelphie. Homme. 2016;3:31–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourgois P, Hart LK. Coming of age in the concrete killing fields of the us inner city. In: MacClancy J, editor. Exotic No More. 2nd Ed Univ Chicago Press; Chicago: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Branas CC, Richmond TS, Culhane DP, Ten Have TR, Wiebe DJ. Investigating the link between gun possession and gun assault. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2034–2040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skogan WG. Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods. Univ California Press; Oakland, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duck W, Rawls AW. The Orderliness of Urban “Disorder”: Drug Dealing “Careers” and the Local Interaction Order of a Place. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisburd D, et al. Does crime just move around the corner? A controlled study of spatial displacement and diffusion. Crim. 2006;44:549–592. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampson N, et al. Landscape care of urban vacant properties and implications for health and safety: Lessons from photovoice. Health Place. 2017;46:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams T. March 4, 2014 Cities mobilize to help those threatened by gentrification. New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/us/cities-helping-residents-resist-the-new-gentry.html. Accessed February 14, 2018.

- 44.Heckert M, Kondo M. Can “cleaned and greened” lots take on the role of public Greenspace? J Plann Educ Res. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0739456X16688766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aiyer SM, Zimmerman MA, Morrel-Samuels S, Reischl TM. From broken windows to busy streets: A community empowerment perspective. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42:137–147. doi: 10.1177/1090198114558590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenberg CE. Cholera in nineteenth-century Europe: A tool for social and economic analysis. Comp Stud Soc Hist. 1966;8:452–463. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.