Abstract

Aim or objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of behavioural interventions that report sedentary behaviour outcomes during early childhood.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Complete, Global Health, MEDLINE Complete, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus with Full Text and EMBASE electronic databases were searched in March 2016.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Inclusion criteria were: (1) published in a peer-reviewed English language journal; (2) sedentary behaviour outcomes reported; (3) randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design; and (4) participants were children with a mean age of ≤5.9 years and not yet attending primary/elementary school at postintervention.

Results

31 studies were included in the systematic review and 17 studies in the meta-analysis. The overall mean difference in screen time outcomes between groups was −17.12 (95% CI −28.82 to −5.42) min/day with a significant overall intervention effect (Z=2.87, p=0.004). The overall mean difference in sedentary time between groups was −18.91 (95% CI −33.31 to −4.51) min/day with a significant overall intervention effect (Z=2.57, p=0.01). Subgroup analyses suggest that for screen time, interventions of ≥6 months duration and those conducted in a community-based setting are most effective. For sedentary time, interventions targeting physical activity (and reporting changes in sedentary time) are more effective than those directly targeting sedentary time.

Summary/conclusions

Despite heterogeneity in study methods and results, overall interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in early childhood show significant reductions, suggesting that this may be an opportune time to intervene.

Trial registration number

CRD42015017090.

Keywords: Sedentary, Child, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Sedentary behaviour is defined as any waking activity requiring ≤1.5 metabolic equivalent of tasks and performed in a sitting or reclining posture1 (eg, television viewing, sitting in a stroller). During early childhood (ie, birth through 5 years2), television viewing has been longitudinally and experimentally associated with excess adiposity, poor psychosocial health and poor cognitive development.3 Additionally, total screen time (comprising television viewing, electronic games and computer use) has been associated with poor psychosocial health4 and delayed cognitive development5 in early childhood. While health outcomes of objectively measured sedentary time in early childhood are yet to be established, evidence suggests that sedentary time is associated with an increased risk of overweight/obesity in school-aged children and youth.6 This is relevant because sedentary behaviours track from early childhood into the school-aged years.7

Recommendations for limiting sedentary behaviour in early childhood have been introduced in numerous countries (eg, Australia, Canada and USA). These suggest that children under 2 years of age engage in no screen time and children aged 2–5 years engage in no more than 1 hour of screen time per day.8–10 Recommendations from Australia and Canada also suggest that children aged 5 years and younger not be restrained (eg, kept inactive in a high chair) for more than 1 hour at a time, except when sleeping.8 9 Evidence suggests that young children in Australia11 and Canada12 engage in around 2 hours of screen time daily, while children in the USA13 engage in it around 4 hours daily. Moreover, up to 83% of children aged 2 years and younger in the USA14 and up to 82% and 78% of children aged 3–5 years in Canada15 and Australia,11 respectively, exceed recommendations for their respective age group. With only one study until now reporting on the percentage of young children kept restrained,16 prevalence of these behaviours remains unclear. Estimates of overall sedentary behaviour for children under 6 years of age using objective measures (eg, accelerometers, observation) range from 23% to 94% of their daily waking time.17 Evidence suggests that many young children engage in less than optimal amounts of sedentary behaviours, highlighting a need for interventions to reduce the prevalence of these behaviours.

While systematic reviews of interventions to increase physical activity or prevent obesity during early childhood have also assessed sedentary behaviour,18–23 none have focused solely on sedentary behaviour outcomes. Sedentary behaviours are a distinct group of behaviours; high levels of sedentary behaviour can be accumulated even when children meet physical activity recommendations (ie, 3 hours or more per day8 24 25). Given this, it may be that behaviour-specific interventions are needed; that is, effective strategies to reduce screen time or time spent restrained may be different from those that are effective at promoting active play. Reviews of interventions specifically targeting sedentary behaviour in young children are required to determine this.

Systematic reviews of interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour across children and adolescents more broadly have been published.26–32 Three of these included a meta-analysis,27–29 which is important for determining the overall effectiveness of interventions. Biddle et al 27 and Maniccia et al 28 both concluded that interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour have a small but significant effect. Conversely, Wahi et al 29 concluded no evidence of effectiveness, but that interventions in the preschool age hold promise. However, no systematic reviews have focused exclusively on the early childhood period. Birth through 5 years of age is a critical developmental period. Children reach a number of important developmental milestones during this time33 and there are stronger parental and family influences given that young children are much less independent than school-aged children and youth. Therefore, strategies shown to be effective in older children may not translate to this younger population. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the effectiveness of behavioural interventions that reported sedentary behaviour outcomes during early childhood.

Methods

This review is registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (number CRD42015017090). The PRISMA Statement34 guidelines were followed in reporting.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in March 2016. EBSCOhost (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Complete, Global Health, MEDLINE Complete, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus with Full Text) and EMBASE databases were searched. Full details of the EBSCOhost search strategy are shown in table 1 (search terms were modified as appropriate for EMBASE). Reference lists of included articles were also reviewed to identify any additional studies.

Table 1.

Search strategy: EBSCOhost

| Search | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | “sedentary behavio*” OR sedentar* OR sitting OR “physical inactivity” OR “screen time” OR screen-time OR “small screen” OR “screen based” OR screen-based OR “electronic media” OR television OR TV OR “electronic game*” OR e-game* OR “e game*” OR computer OR video OR DVD OR “video games” OR restraint OR restrained OR stroller OR “high chair” OR “play pen” OR playpen OR “baby carrier” OR “car seat” |

| 2 | infan* OR baby OR babies OR toddler* OR “young child*” OR child* OR “early childhood” OR “early years” OR preschool* OR pre-school* |

| 3 | intervention* OR trial OR “randomi*ed controlled trial” OR RCT OR “primary prevention” |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

One author (KLD) reviewed titles identified in the initial search. Two authors (KLD and JAH) then independently reviewed the included abstracts; abstracts were excluded when both authors deemed that the study did not meet inclusion criteria for the review. The same two authors then reviewed the full text of the remaining articles to determine final inclusion. Inconsistencies were resolved with discussion between those two authors or, if consensus could not be reached, with all other authors.

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) published in a peer-reviewed English language journal; (2) study reported sedentary behaviour outcomes; (3) randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design was employed; and (4) participants were children with a mean age of 5.9 years or younger and not yet attending primary/elementary school at postintervention. No restrictions were placed on the publication period or intervention setting. Where more than one study reported results from the same sample, the study that reported sedentary behaviour as a main outcome was included.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a standardised form by one author (KLD) and included: study characteristics (eg, country, year); participant characteristics (eg, sample size, age, sex); intervention components (eg, setting, duration, content); sedentary behaviour measure (eg, objective measure, parent report); and changes in the outcome (eg, change in sedentary behaviour).

Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

Study quality and risk of bias were assessed independently by two authors (KLD and JAH) using a modified published rating scale.35 Six methodological components were assessed: (1) selection bias (eg, sample representativeness); (2) study design (eg, RCT); (3) confounders (eg, controlling for baseline differences between groups); (4) blinding (eg, whether the outcome assessor was aware of group allocation); (5) validity and reliability of data collection methods (eg, whether the tool(s) to measure sedentary behaviour were reported to be valid and reliable, with appropriate supporting information such as criteria or references); and (6) withdrawals and dropouts (eg, whether withdrawals were reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons). Each component was given a quality score of weak, moderate or strong, in line with the accompanying instructions for the tool. Components that were not reported were given a weak rating. As recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,36 no overall quality/risk of bias score was produced. Initial inter-rater reliability between the two authors (determined using Cohen's κ coefficient) was 80% (κ=0.71). Discrepancies in assessment between authors were discussed until consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager V.5.3 (Revman; The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The mean (SD) between-groups difference in screen time and/or sedentary time from baseline to postintervention was extracted from studies and entered into Revman. Where reported, the adjusted mean difference was used. If not reported, the mean difference was calculated in Stata V.13.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). A random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis.37 Heterogeneity was assessed through observation of the χ2 (Q) and I2 statistics. A Q value with a significance of p≤0.05 was considered significant heterogeneity, while for the I2 value 25% was considered low, 50% was considered moderate and 75% was considered high heterogeneity.38 A priori, it was decided that if high heterogeneity was present, subgroup analyses would be conducted for child age, intervention duration, intervention setting and targeted behaviour/s (whether the intervention aimed to increase physical activity and simply reported sedentary time results, or directly targeted decreasing sedentary time). Post hoc, it was decided to include the type of sedentary cut point used (ie, a ‘low’ vs a ‘high’ cut point) as a potential moderator in the sedentary time meta-analysis.

Results

Study characteristics

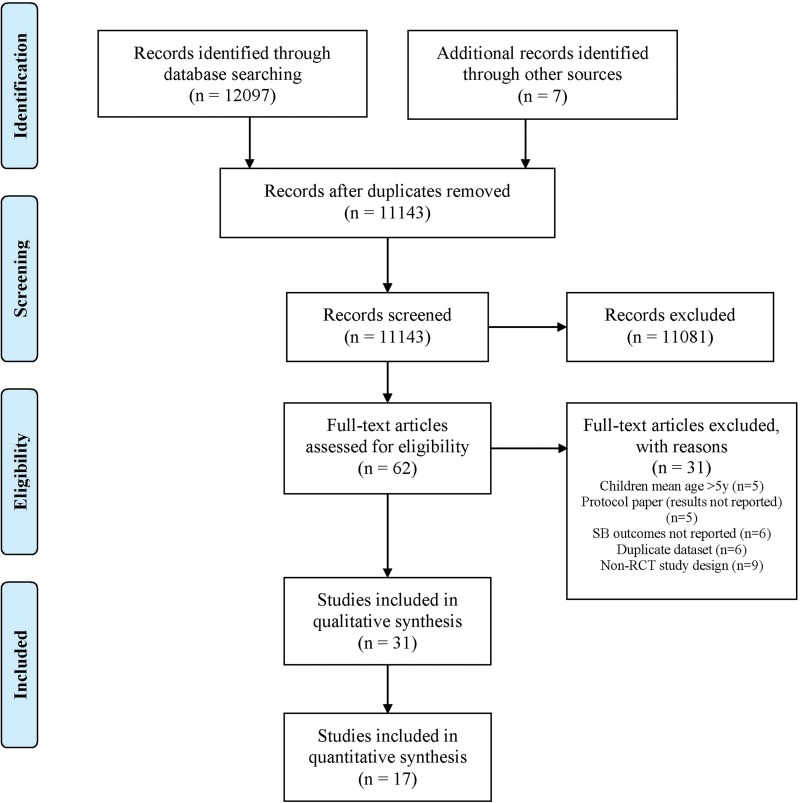

The number of studies identified and excluded at each stage is shown in figure 1 (PRISMA Statement34 flow diagram). Thirty-one studies met the inclusion criteria; a summary of included studies is presented in online supplementary table S1. The majority of included studies (n=29) used a cluster-based sampling design. Of the included studies, 18 reported changes in screen time, 8 reported changes in sedentary time (measured by accelerometry or direct observation), 4 reported changes in screen time and sedentary time, and 1 reported changes in screen time and parent-reported sedentary behaviour. No studies were identified that aimed to specifically reduce (or reported changes in) time spent restrained. Approximately half of the studies (n=15) were conducted in the USA,39–53 five in Australia,54–58 three in Belgium,59–61 two in the UK62 63 and one each in Canada,64 Germany,65 Switzerland,66 the Netherlands,67 Israel68 and Turkey.69 Five studies included participants with a mean age under 3 years,54 55 60 63 70 whereas the remainder targeted preschool-aged children (3–5 years). Intervention duration ranged from a once-off session to 24 months. The majority of interventions (n=23; 74.2%) were 10 weeks or longer in duration. Sample sizes ranged from 2255 to 88552 participants. Studies were conducted in a range of settings, including preschools/kindergartens/day care centres,40 41 43–46 48 51 52 58–63 65 66 68 the home,39 42 49 50 53 69 70 primary care settings (eg, paediatric offices)47 64 67 and community-based settings.54 55 57 Results are discussed below, by setting.

Figure 1.

PRISMA statement flow chart. RCT, randomised controlled trial; SB, sedentary behaviour.

bjsports-2016-096634supp001.pdf (283.5KB, pdf)

Screen time

Preschool/day care setting

Nine studies targeting screen time were conducted in the preschool/kindergarten setting and 1 in a day/childcare setting. Of the 9 preschool interventions, 8 implemented child educational sessions (either alone or in conjunction with physical activity/movement breaks and/or parent education) with topics relating to a range of health behaviours (ie, nutrition, physical activity, screen time and/or sleep). Three of these reported significant between-group differences in screen time ranging from 13 to 40 min/day, in favour of the intervention group.41 46 66 One study found no intervention effect for the entire sample, but small effects for some behaviours in some subgroups.61 The remaining 4 studies using child education strategies did not report significant intervention effects on screen time.43–45 68 The 1 study in this setting that did not use child education sessions implemented a number of preschool policy changes, including healthy menu changes and changes to screen time practices, in addition to parent education sessions and newsletters.40 While that study found no screen time differences between groups postintervention, they found that children in control centres had significantly greater increases across the intervention in computer use (p<0.01) and watching television (p<0.0001) than children in intervention centres. The one study conducted in a day care centre (targeting children under 2 years) provided parents with an informative poster and tailored feedback on their child's physical activity, sedentary behaviour and diet-related behaviours and found no significant differences between groups postintervention.60

Home setting

Of the 7 studies conducted in the home setting, 4 were successful in reducing screen time.39 50 69 70 Two of those studies35 46 used face-to-face contact (eg, motivational counselling, in-person conferences), in addition to mailed or emailed educational materials/resources and phone contact. Both found significant differences in daily television viewing, of 37 and 64 min/day, respectively, in favour of the intervention group. One of the other studies that successfully decreased screen time was delivered remotely (ie, via mailed materials and one phone call), and found a significant difference of around 47 min/day of screen time postintervention (p<0.001).69 The remaining successful study was delivered in the home by trained nurses providing education to mothers around active play and family physical activity.70 That study found a significantly lower percentage of children in the intervention compared to the control group watching television for more than 60 min a day (14% v 22%, p=0.02) postintervention. The 3 non-successful studies employed an in-home counselling session for parents and educational materials,42 monthly mailed interactive kits (including child activities and incentives) followed by motivational interviewing telephone calls,49 and online parent education sessions.53

Primary-care setting

Three studies were conducted in a primary care setting, of which 2 were effective at decreasing screen time. One study consisted of a once-off session (length not specified) around diet, outside play and television viewing and found that intervention group children were significantly less likely to watch more than 2 hours of television per day compared with controls.67 The other study involved four face-to-face sessions and three phone calls. It showed a significant decrease in television viewing of around 22 min/day for the intervention compared to usual care group.47 The non-successful study used one 10 min behavioural counselling session on health impacts and strategies to decrease screen time.64

Community-based setting

Finally, 3 studies were conducted in a community-based setting; of those, only one reported significant findings. Campbell et al 54 conducted a 15-month dietitian-delivered intervention with parents in their existing first-time parent groups, using anticipatory guidance around diet, physical activity and screen time. They found a significant difference in television viewing between intervention and control groups postintervention of 16 min/day (at child age 19 months). One of the non-successful studies used anticipatory guidance to facilitate group discussions around screen time recommendations, outcomes of screen time and strategies to participate in healthy levels of screen time.55 The other implemented weekly workshops for parents and children, including guided active play, healthy snack time, interactive education and skill development for parents and supervised creative play for children.57

Sedentary time

Preschool/day care setting

Nine of the 13 studies that reported changes in sedentary time were conducted in preschools and 1 was conducted in childcare centres. Of those, 4 were effective at decreasing sedentary time, 3 of which had a primary aim to increase physical activity,48 51 65 and one which targeted sedentary time directly. Two physical activity interventions had no parental involvement and reported significant differences of 41–51 min less sedentary time per day between intervention and control groups.48 51 The other study augmented an existing physical activity programme at preschools with parental involvement and found that, compared with controls, children in intervention preschools spent 11 min less in sedentary time per day (p=0.019).65 The study that specifically targeted sedentary behaviour involved environmental changes in the classroom (eg, computers on a raised desk), movement breaks, stories and activities for children and newsletters for parents.61 That study did not find an intervention effect on sedentary time overall; however, there was a significant decrease in sedentary time on weekdays (p=0.03) and during school hours (p=0.04) for children from high socioeconomic area kindergartens. The 6 non-successful interventions in this setting used physical activity lessons/programmes,52 62 parent education sessions,43 63 play equipment and markings in the playground59 and implementation of physical activity policies and practices.58

Home setting

One study was conducted in the home.49 It used mailed interactive kits including child activities and incentives followed by telephone coaching sessions, but found no significant effect.

Community-based setting

Two studies were conducted in community-based settings; neither was successful at reducing sedentary time. One used parent education and anticipatory guidance in group discussions.55 The other implemented weekly guided play and education workshops for parents and children.57

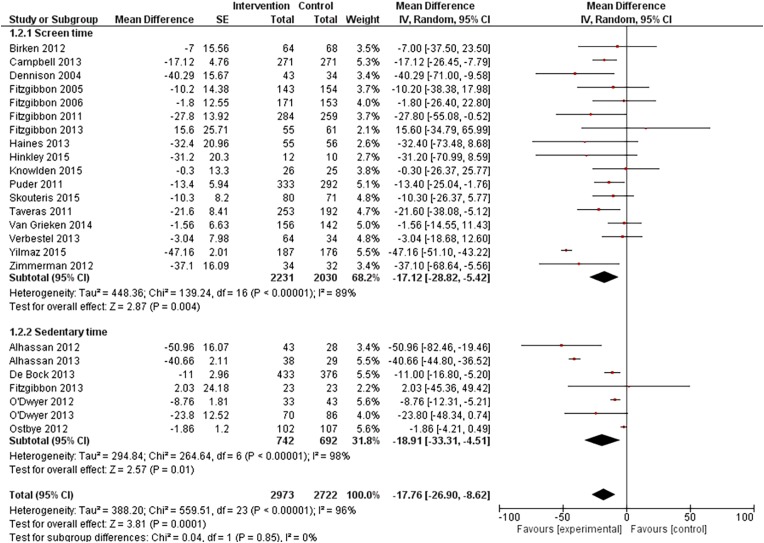

Meta-analysis

Seventeen studies reporting a continuous measure of screen time and seven reporting a continuous measure of sedentary time were included in the meta-analysis. A forest plot of the mean difference, in minutes per day spent in screen time and sedentary time, is presented in figure 2. The overall mean difference for both screen time and sedentary time between intervention and control groups was −17.76 (95% CI −26.90 to −8.62), with a significant overall effect of Z=3.81 (p=0.0001). The overall mean difference in screen time was −17.12 (95% CI −28.82 to −5.42) minutes per day with a significant overall intervention effect (Z=2.87, p=0.004). The overall mean difference in sedentary time between groups was slightly higher than screen time, at −18.91 (95% CI −33.31 to −4.51); however, the intervention effect was slightly lower (Z=2.57, p=0.01).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the mean overall difference (95% CI) for each study included in the meta-analysis.

Examination of heterogeneity statistics revealed very high heterogeneity for both screen time and sedentary time results (χ2=139.24 (p=<0.00001), I2=89% and χ2=264.64 (p<0.00001), I2=98%, respectively). Hence, as decided a priori, subgroup analyses were conducted for child age, intervention duration, intervention setting and targeted behaviour/s (whether the intervention aimed to increase physical activity and simply reported sedentary time results, or directly targeted decreasing sedentary time). However, for sedentary time, all of the studies included in the meta-analysis involved preschool-aged children and 6 of the 7 studies were conducted in preschools. Owing to the lack of variability in these characteristics for sedentary time outcomes, subgroup analyses were only conducted for intervention duration and targeted behaviour/s. Tables 2 and 3 present results of these subgroup analyses for screen time and sedentary time, respectively.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses for studies reporting screen time outcomes

| Number of studies | Mean difference (min/day) | 95% CIs |

Heterogeneity within subgroups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Lower | Upper | Z | p Value | χ2 | I2 (%) | p Value | ||

| Duration of intervention | |||||||||

| Short (<6 months) | 11 | −15.45 | −32.63 | 1.73 | 1.76 | 0.08 | 93.36 | 89 | <0.00001 |

| Long (≥6 months) | 6 | −16.14 | −23.33 | −8.94 | 4.39 | <0.0001 | 6.34 | 21 | <0.0001 |

| Behaviours targeted | |||||||||

| Targeted SB alone | 4 | −34.24 | −53.53 | −14.95 | 3.48 | 0.0005 | 7.44 | 60 | 0.06 |

| Targeted SB, PA and diet | 13 | −12.19 | −17.72 | −6.65 | 4.31 | <0.0001 | 14.38 | 17 | 0.28 |

| Child age | |||||||||

| <3 years | 4 | −13.17 | −20.70 | −5.64 | 3.43 | 0.0006 | 3.21 | 6 | 0.36 |

| ≥3 years | 13 | −18.20 | −32.54 | −3.87 | 2.49 | 0.01 | 100.65 | 88 | <0.00001 |

| Setting | |||||||||

| Preschool/childcare | 7 | −11.97 | −21.41 | −2.54 | 2.49 | 0.01 | 7.69 | 22 | 0.26 |

| Home | 4 | −30.55 | −54.80 | −6.31 | 2.47 | 0.01 | 12.86 | 77 | 0.005 |

| Community-based (eg, community venues) | 3 | −16.03 | −23.93 | −8.12 | 3.97 | <0.0001 | 1.10 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Healthcare centre/paediatric office | 3 | −9.91 | −23.88 | 4.05 | 1.39 | 0.16 | 3.52 | 43 | 0.17 |

PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses for studies reporting sedentary time outcomes

| 95% CIs |

Heterogeneity within subgroups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup* | Number of studies | Mean difference (min/day) | Lower | Upper | Z | p Value | χ2 | I2 (%) | p Value |

| Duration of intervention | |||||||||

| Short (<6 months) | 4 | −20.71 | −44.73 | 3.32 | 1.69 | 0.09 | 132.70 | 98 | <0.00001 |

| Long (≥6 months) | 3 | −10.97 | −22.60 | 0.67 | 1.85 | 0.06 | 17.00 | 88 | 0.0002 |

| Behaviours targeted | |||||||||

| Targeted PA alone | 3 | −31.90 | −56.88 | −6.92 | 2.50 | 0.01 | 68.15 | 97 | <0.00001 |

| Targeted PA and SB | 4 | −6.22 | −12.78 | 0.35 | 1.86 | 0.06 | 12.65 | 76 | 0.005 |

| Sedentary cut point | |||||||||

| Low cut point† | 3 | −5.74 | −13.95 | 2.46 | 1.37 | 0.17 | 8.23 | 76 | 0.02 |

| High cut point‡ | 4 | −29.54 | −52.89 | −6.19 | 2.48 | 0.01 | 134.85 | 98 | <0.00001 |

*Subgroup analyses for behaviours age and setting not performed for sedentary time outcomes due to lack of variability in studies.

†Low cut points included Evenson sedentary cut point: ≤15 counts/15 s, Pfeiffer sedentary cut point: <38 counts/15 s, and De Bock sedentary cut points: boys <46 counts/15 s.

‡High cut point included Sirard sedentary cut points: 3 years ≤301 counts/15 s, 4 years ≤363 counts/15 s, 5 years ≤398 counts/15 s.

PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour.

Results suggest that the most effective interventions for screen time were long duration (≥6 months; Z=4.39, p<0.0001) and conducted in a community-based (eg, community venue; Z=3.97, p<0.0001), home (Z=2.47, p=0.01) or preschool/childcare setting (Z=2.49, p=0.01). In subgroup analyses of the targeted behaviours, results suggest a significant effect regardless of whether the study targeted sedentary behaviour alone (Z=3.48, p=0.0005) or included diet and physical activity (Z=4.31, p<0.0001). Similarly subgroup analyses for age indicate a significant intervention effect both for studies with children aged younger than 3 years and for studies with children aged 3–5 years (Z=3.43, p=0.0006 and Z=2.49, p=0.01, respectively). However, there was high heterogeneity in the 3–5-year subgroup (χ2=100.65 (p<0.00001), I2=88%), which was not evident in the younger than 3-year subgroup (χ2=3.21 (p=0.36), I2=6%), suggesting that there may be other moderating factors influencing outcomes for the older age group.

For sedentary time, results of subgroup analyses show no differences for intervention length, with both short-duration and long-duration interventions found to be not significant. However, long-duration interventions approached significance (Z=1.85, p=0.06). Interventions that targeted physical activity alone, but reported sedentary time results, were shown to be more effective (Z=2.50, p=0.01) than interventions that actually aimed to decrease sedentary time in addition to promoting physical activity (Z=1.86, p=0.06). With respect to the moderator analysis for type of sedentary cut point used, 3 studies43 49 65 were classified as using a ‘low’ cut point (<15 counts, <38 counts or <46 counts/15 s epoch) and 4 studies48 51 62 63 were classified as using a ‘high’ cut point (3-year-old ≤301 counts, 4-year-old ≤363 counts, 5-year-old ≤398 counts/15 s epoch). Results of the analysis suggest that studies using a high cut point had a significant overall effect (Z=2.48, p=0.01), while those using a low cut point did not (Z=1.37, p=0.17).

Methodological quality and risk of bias

Scores for each study are presented in table 4. Briefly, most studies scored moderate quality for selection bias; all scored strong for study design; the majority scored strong for confounders; the majority scored moderate for blinding; almost half scored weak for data collection methods; and the majority scored strong for withdrawals and dropouts.

Table 4.

Methodological quality for included studies

| Author, year | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection methods | Withdrawals and dropouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alhassan et al, 201248 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Alhassan et al, 201351 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Annesi et al, 201352 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Birken et al, 201264 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong |

| Campbell et al, 201354 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Cardon et al, 200959 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| De Bock et al, 201365 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| De Craemer et al, 201661 | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Dennison et al, 200441 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Evans et al, 201142 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Fitzgibbon et al, 200544 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Fitzgibbon et al, 200645 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak | Strong |

| Fitzgibbon et al, 201146 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Fitzgibbon et al, 201343 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Haines et al, 201339 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Hinkley et al, 201555 | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Jones et al, 201558 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Knowlden et al, 201553 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Lerner-Geva et al, 201568 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Natale et al, 201440 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| O'Dwyer et al, 201263 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| O'Dwyer et al, 201362 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| Østbye et al, 201249 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Puder et al, 201166 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Skouteris et al, 201557 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Taveras et al, 201147 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| van Grieken 201467 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Verbestel et al, 201360 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Wen et al, 201256 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Yilmaz et al, 201569 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong |

| Zimmerman et al, 201250 | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed interventions that reported changes in young children's sedentary behaviours. Thirty-one RCTs were included in the review, of which 17 were included in a screen time meta-analysis and 7 in a total sedentary time meta-analysis. Results of the meta-analyses suggest that interventions to reduce screen time and sedentary time have a statistically significant postintervention effect of around 17 and 19 min/day (favouring the intervention group), respectively. Given that evidence suggests preschool-aged children spend ∼2 hours/day on screen time,11 12 a reduction of 17 min is promising. Similarly, results for sedentary time are encouraging, particularly considering their benefits for physical activity. For young children, physical activity recommendations encompass light-intensity, moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity (ie, anything but sedentary time). Hence, a 19 min reduction in sedentary time may potentially equate to an increase in physical activity of up to 19 min, 10% of the recommended 3 hours daily. It is also important to consider the variability in findings between studies; some studies showed decreases in sedentary time of up to almost 1 hour, suggesting that larger decreases are possible within these behavioural interventions. However, given that children may be spending up to 12 hours/day sedentary,17 compared to around 2 hours/day on screen time, there is greater scope for reduction in sedentary time.

Subgroup meta-analyses showed some trends in studies that reported screen time outcomes; however, given the small number of studies included in some subgroups, results should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, results do suggest that screen time interventions with a duration of 6 months or longer are more effective than shorter interventions. In a meta-analysis of children's (0–18 years) sedentary behaviour, Biddle et al 27 found that interventions of more than 12 months duration were more effective than 5–12-month interventions. Only four studies included in this meta-analysis had a duration of 12 months or longer; therefore, dichotomising at 6 months was more appropriate. Given that screen time is a habitual behaviour that may be hard to change, perhaps interventions of longer duration are required to change the habits of both parents/carers and children in order to decrease young children's time in this behaviour.

Results also suggest that interventions conducted in a home, community-based or preschool/childcare setting are more effective at reducing children's screen time than those conducted in a healthcare centre/paediatric office setting. In particular, community-based interventions had the highest overall effect and very low heterogeneity. Interventions with greater parent focus may be more effective given the strong parental influence on children of this young age. While the three interventions conducted in a healthcare setting/paediatric office also had parental involvement, they were all implemented at a scheduled health visit. Hence, despite the face-to-face nature of the interventions, parents may have been more focused on their child's general health and not receptive to behavioural messages. Moreover, 2 of those 3 studies involved only a short, once-off session and hence may not have been long enough to result in significant behaviour changes. While interventions conducted in the preschool/childcare setting were the most common and showed a significant overall effect in the meta-analysis, only three of the seven included studies had a significant intervention effect. This suggests that while the preschool setting is regularly targeted as a convenient setting for behavioural interventions, it may not be the most effective. This has been similarly noted in other reviews of interventions in this age group, with lack of parental involvement suggested as a potential reason for the lower efficacy in this setting.19

Results of the subgroup analysis for age showed a larger overall effect on screen time for studies that targeted younger (<3 years) compared to older ( 3–5 years) children. However, the vast majority of studies targeted the older age group. Wahi et al 29 found that interventions aimed at reducing screen time in children aged ≤18 years were not effective, but that the preschool age group did hold promise. The current review supports this, and suggests that interventions may be more beneficial when aimed at even younger children. It is unclear whether this observation is related directly to the age of the children or is a reflection of the format and setting of interventions for the younger age group. As already noted, interventions conducted in the preschool setting showed limited effectiveness. Clearly, further research into children younger than 3 years is warranted.

While fewer studies were included in the meta-analysis for sedentary time, and the overall intervention effect was smaller than for the screen time meta-analysis, results nonetheless showed a significant overall effect with a similar reduction in daily minutes to screen time. However, there was extremely high heterogeneity among these studies. Subgroup analyses suggest that interventions targeting increases in physical activity, but not those directly targeting sedentary time, had a significant overall intervention effect. Physical activity guidelines for young children include light-intensity, moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity. It may be that increasing physical activity is an effective strategy for reducing sedentary time in young children, by shifting time spent sedentary along the spectrum of activity.

A limitation of this review is that some studies could not be included in the meta-analysis due to non-continuous measures of screen or sedentary time being reported. Therefore, fewer studies were included in the meta-analysis than in the systematic review; it is possible that the inclusion of these studies could modify the results observed. Limitations of the individual studies included in the review must also be considered. A number of pilot studies with relatively small sample sizes were included. These studies may not have been powered to detect small changes in sedentary behaviours, potentially influencing the meta-analysis results. Moreover, the studies included in the review varied widely in their intervention objectives, settings, methodologies and modes, making it difficult to compare findings. This is highlighted by the high heterogeneity observed in most of the meta-analyses undertaken. Finally, individual study quality varied greatly. Few studies scored ‘strong’ ratings for selection bias, blinding or data collection methods. While this may be due to lack of reporting (as opposed to actual poor methodologies), it is important to note. A recent review of correlates of physical activity reported similar findings in terms of study quality.71 Future RCTs would benefit from following the CONSORT statement72 when reporting results.

Results of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that interventions targeting screen time would benefit from being longer in duration (ie, ≥6 months) and conducted in a setting with high parental involvement. This review also highlighted the relatively few studies undertaken in children aged under 3 years and outside the preschool setting. Further research is required to investigate different strategies for reducing objectively assessed sedentary time in early childhood; the considerable heterogeneity of studies and lack of clear trends in subgroup analyses make it difficult to draw conclusions about the types of interventions or strategies that are effective in this population. It will also be important for future interventions to target and include measures of screen time beyond just television viewing. With technology such as smartphones and tablets becoming ubiquitous, and often used as a ‘babysitting’ tool, parents may be underestimating their child's screen time. In addition, future interventions should consider targeting child restraint, given that a number of countries have recommendations for limiting the amount of time children spend restrained. Until now, no interventions have been identified that target time spent restrained in early childhood.

Conclusions

Given the negative health outcomes associated with some sedentary behaviours in early childhood,3 4 it is vital to investigate effective strategies to reduce time in these behaviours. Results from this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that interventions to decrease screen time and sedentary time in children aged birth through 5 years have a relatively large, statistically significant overall effect. This supports the implementation of interventions in early childhood to reduce sedentary behaviours, and suggests that this appears to be an ideal age to intervene.

What are the findings?

Interventions to reduce screen time and overall sedentary behaviour in early childhood have a significant overall effect of 17 and 19 min/day, respectively.

Few interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour have been conducted in children younger than 3 years and outside the preschool setting, suggesting that further research is needed.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the future?

Early childhood may be an opportune time to intervene to reduce sedentary behaviour.

Future interventions would benefit from being longer in duration (>6 months) and having high parent involvement.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Katherine Downing at @kdowning_

Contributors: KLD conceptualised the study, carried out the database searches, screened the titles, abstracts and full-text papers, extracted the data, conducted the quality assessment, conducted the meta-analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. JAH screened the abstracts and full-text papers, conducted the quality assessment, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. TH, JS and KDH were consulted where necessary for full-text inclusion, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: KLD is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship (GNT1092876). TH is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (APP1070571). JS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (APP1026216). KDH is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT130100637) and an Honorary Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (100370).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:540–2. 10.1139/h2012-024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Timmons BW, LeBlanc AG, Carson V, et al. . Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0–4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:773–92. 10.1139/h2012-070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. LeBlanc AG, Spence JC, Carson V, et al. . Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:753–72. 10.1139/h2012-063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hinkley T, Teychenne M, Downing KL, et al. . Early childhood physical activity, sedentary behaviors and psychosocial well-being: a systematic review. Prev Med 2014;62:182–92. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carson V, Kuzik N, Hunter S, et al. . Systematic review of sedentary behavior and cognitive development in early childhood. Prev Med 2015;78:115–22. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, et al. . Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:98 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones RA, Hinkley T, Okely AD, et al. . Tracking physical activity and sedentary behavior in childhood: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:651–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Australian Government Department of Health. Move and play every day: national physical activity recommendations for children 0-5 years. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines. Ottowa: CSEP, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Council On Communications and Media. Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 2013;132:958–61. 10.1542/peds.2013-2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hinkley T, Salmon J, Okely AD, et al. . Preschoolers’ physical activity, screen time, and compliance with recommendations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:458–65. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318233763b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carson V, Spence JC, Cutumisu N, et al. . Association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and screen time among pre-school children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:367–7. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tandon PS, Zhou C, Lozano P, et al. . Preschoolers’ total daily screen time at home and by type of childcare. J Pediatr 2011;158:297–300. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Certain LK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics 2002;109:634–42. 10.1542/peds.109.4.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colley RC, Garriguet D, Adamo KB, et al. . Physical activity and sedentary behavior during the early years in Canada: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:54 10.1186/1479-5868-10-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hesketh KD, Crawford DA, Abbott G, et al. . Prevalence and stability of active play, restricted movement and television viewing in infants. Early Child Dev Care 2014;185:883–94. 10.1080/03004430.2014.899592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hnatiuk JA, Salmon J, Hinkley T, et al. . A review of preschool children's physical activity and sedentary time using objective measures. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:487–97. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell KJ, Hesketh KD. Strategies which aim to positively impact on weight, physical activity, diet and sedentary behaviours in children from zero to five years. A systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2007;8:327–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hesketh KD, Campbell KJ. Interventions to prevent obesity in 0-5-year-olds: an updated systematic review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(Suppl 1):S27–35. 10.1038/oby.2009.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bluford DAA, Sherry B, Scanlon KS. Interventions to prevent or treat obesity in preschool children: a review of evaluated programs. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1356–72. 10.1038/oby.2007.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ward DS, Vaughn A, McWilliams C, et al. . Interventions for increasing physical activity at childcare. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:526–34. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181cea406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monasta L, Batty GD, Macaluso A, et al. . Interventions for the prevention of overweight and obesity in preschool children: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2011;12:e107–e18. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Skouteris H, McCabe M, Swinburn B, et al. . Parental influence and obesity prevention in pre-schoolers: a systematic review of interventions. Obes Rev 2011;12:315–28. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Carson V, et al. , Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0-4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:345–69. 10.1139/h2012-018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. UK Department of Health. Start active, stay active. London: UK Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26. DeMattia L, Lemont L, Meurer L. Do interventions to limit sedentary behaviours change behaviour and reduce childhood obesity? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev 2007;8:69–81. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biddle SJ, O'Connell S, Braithwaite RE. Sedentary behaviour interventions in young people: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:937–42. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maniccia DM, Davison KK, Marshall SJ, et al. . A meta-analysis of interventions that target children's screen time for reduction. Pediatrics 2011;128:e193–210. 10.1542/peds.2010-2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wahi G, Parkin PC, Beyene J, et al. . Effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing screen time in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:979–86. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schmidt ME, Haines J, O'Brien A, et al. . Systematic review of effective strategies for reducing screen time among young children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:1338–54. 10.1038/oby.2011.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steeves JA, Thompson DL, Bassett DR, et al. . A review of different behavior modification strategies designed to reduce sedentary screen behaviors in children. J Obes 2012;2012:379215 10.1155/2012/379215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marsh S, Foley LS, Wilks DC, et al. . Family-based interventions for reducing sedentary time in youth: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2014;15:117–33. 10.1111/obr.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sigelman C, Rider E. Life-span human development. 7th edn Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cenage Learning, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Quality assessment tool for quantitative Studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, 2008. http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/14.html [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Littell JH, Corcoran J, Pillai V. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haines J, McDonald J, O'Brien A, et al. . Healthy Habits, Happy Homes: randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:1072–9. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Natale RA, Lopez-Mitnik G, Uhlhorn SB, et al. . Effect of a childcare center-based obesity prevention program on body mass index and nutrition practices among preschool-aged children. Health Promot Pract 2014;15:695–705. 10.1177/1524839914523429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dennison BA, Russo TJ, Burdick PA, et al. . An intervention to reduce television viewing by preschool children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:170–6. 10.1001/archpedi.158.2.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Evans WD, Christoffel KK, Necheles J, et al. . Outcomes of the 5-4-3-2-1 Go! Childhood Obesity Community Trial. Am J Health Behav 2011;35:189–98. 10.5993/AJHB.35.2.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. . Family-based hip-hop to health: outcome results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:274–83. 10.1038/oby.2012.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. . Two-year follow-up results for Hip-Hop to Health Jr.: a randomized controlled trial for overweight prevention in preschool minority children. J Pediatr 2005;146:618–25. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. . Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1616–25. 10.1038/oby.2006.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer LA, et al. . Hip-hop to Health Jr. Obesity Prevention Effectiveness Trial: postintervention results. Obesity 2011;19:994–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, et al. . Randomized controlled trial to improve primary care to prevent and manage childhood obesity: the high five for kids study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:714–22. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alhassan S, Nwaokelemeh O, Ghazarian M, et al. . Effects of locomotor skill program on minority preschoolers’ physical activity levels. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2012;24:435–49. 10.1123/pes.24.3.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Østbye T, Krause KM, Stroo M, et al. . Parent-focused change to prevent obesity in preschoolers: results from the KAN-DO study. Prev Med 2012;55:188–95. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zimmerman FJ, Ortiz SE, Christakis DA, et al. . The value of social-cognitive theory to reducing preschool TV viewing: a pilot randomized trial. Prev Med 2012;54:212–18. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alhassan S, Nwaokelemeh O, Lyden K, et al. . A pilot study to examine the effect of additional structured outdoor playtime on preschoolers’ physical activity levels. Childcare Pract 2013;19:23–35. 10.1080/13575279.2012.712034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Annesi JJ, Smith AE, Tennant GA. Effects of a cognitive–behaviorally based physical activity treatment for 4- and 5-year-old children attending US preschools. Int J Behav Med 2013;20:562–6. 10.1007/s12529-013-9361-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Knowlden AP, Sharma M, Cottrell RR, et al. . Impact Evaluation of Enabling Mothers to Prevent Pediatric Obesity Through Web-Based Education and Reciprocal Determinism (EMPOWER) Randomized Control Trial. Health Educ Behav 2015;42:171–84. 10.1177/1090198114547816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Campbell KJ, Lioret S, McNaughton SA, et al. . A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity risk behaviors: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2013;131:652–60. 10.1542/peds.2012-2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hinkley T, Cliff DP, Okely AD. Reducing electronic media use in 2-3 year-old children: feasibility and efficacy of the Family@play pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2015;15:779 10.1186/s12889-015-2126-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, et al. . Healthy Beginnings Trial Phase 2 study: follow-up and cost-effectiveness analysis. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:396–401. 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Skouteris H, Hill B, McCabe M, et al. . A parent-based intervention to promote healthy eating and active behaviours in pre-school children: evaluation of the MEND 2–4 randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Obes 2016;11:4–10. 10.1111/ijpo.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones J, Wyse R, Finch M, et al. . Effectiveness of an intervention to facilitate the implementation of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in childcare services: a randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2015;10:147. 10.1186/s13012-015-0340-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cardon G, Labarque V, Smits D, et al. . Promoting physical activity at the pre-school playground: the effects of providing markings and play equipment. Prev Med 2009;48:335–40. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Verbestel V, De Coen V, Van Winckel M, et al. . Prevention of overweight in children younger than 2 years old: a pilot cluster-randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1384–92. 10.1017/S1368980013001353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De Craemer M, De Decker E, Verloigne M, et al. . The effect of a cluster randomised control trial on objectively measured sedentary time and parental reports of time spent in sedentary activities in Belgian preschoolers: the ToyBox-study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:1–17. 10.1186/s12966-015-0325-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. O'Dwyer MV, Fairclough SJ, Ridgers ND, et al. . Effect of a school-based active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. Health Educ Res 2013;28:931–42. 10.1093/her/cyt097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O'Dwyer MV, Fairclough SJ, Knowles Z, et al. . Effect of a family focused active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:117–29. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Birken CS, Maguire J, Mekky M, et al. . Office-based randomized controlled trial to reduce screen time in preschool children. Pediatrics 2012;130:1110–15. 10.1542/peds.2011-3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. De Bock F, Genser B, Raat H, et al. . A participatory physical activity intervention in preschools: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2013;45: 64–74. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Puder JJ, Marques-Vidal P, Schindler C, et al. . Effect of multidimensional lifestyle intervention on fitness and adiposity in predominantly migrant preschool children (Ballabeina): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;343:d6195 10.1136/bmj.d6195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. van Grieken A, Renders CM, Veldhuis L, et al. . Promotion of a healthy lifestyle among 5-year-old overweight children: health behavior outcomes of the ‘Be active, eat right’ study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:59 10.1186/1471-2458-14-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lerner-Geva L, Bar-Zvi E, Levitan G, et al. . An intervention for improving the lifestyle habits of kindergarten children in Israel: a cluster-randomised controlled trial investigation. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1537–44. 10.1017/S136898001400024X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yilmaz G, Demirli Caylan N, Karacan CD. An intervention to preschool children for reducing screen time: a randomized controlled trial. Childcare Health Dev 2015;41:443–9. 10.1111/cch.12133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, et al. . Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children's BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:e3732 10.1136/bmj.e3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bingham DD, Costa S, Hinkley T, et al. . Physical activity during the early years: a systematic review of correlates and determinants. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:384–402. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2016-096634supp001.pdf (283.5KB, pdf)