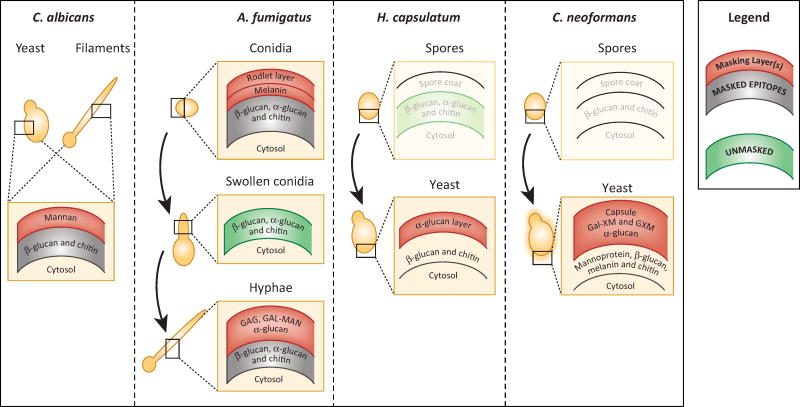

Figure 2. Fungi differentiate to change their function and form, and their cell wall architecture is designed to mask some epitopes from immune recognition.

The simplified cell wall architectures of select human pathogenic fungi are depicted schematically (adapted from [47]). The outer cell wall layers (shown in red) of Candida, Aspergillus, Histoplasma and Cryptococcus forms are generally capable of preventing pattern recognition receptors from binding to ligands that are buried within inner layers of the cell wall (shown in gray to indicate masking). The polysaccharide and protein components of the outer layers differ among pathogenic fungi. In some cases, such as A. fumigatus swollen conidia, rapid growth leads to the temporary unmasking of underlying epitopes, but in most cases during in vitro growth only small proportions of the cell wall are sufficiently unstructured to allow binding of immune receptors to inner polysaccharide molecules (shown in green to indicate surface exposure). Morphological transitions (indicated by curved arrows) that occur during infection by Aspergillus, Histoplasma and Cryptococcus are associated with cell wall changes that affect epitope exposure. Not much is known about the cell wall architecture of H. capsulatum or C. neoformans spores, so the layering is still unknown and these schematics are drawn in faded colors.