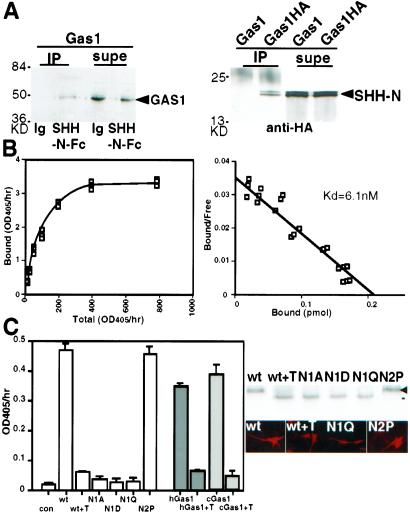

Figure 2.

SHH-N binds GAS1 and the binding depends on the N-glycosylation of GAS1. (A) GAS1 and SHH-N immunoprecipitate each other. (Left) GAS1 expressed on 293EBNA cells was precipitated by SHH-N-Fc but not by IgG (Ig) with protein A. The supernatant (supe) was lysate containing unbound GAS1. (Right) GAS1-HA precipitated recombinant SHH-N in the presence of anti-HA. The supernatant contained the unbound SHH-N. GAS1-HA and SHH-N (arrowheads) were detected by Western blots. (B) The binding data (Left) and Scatchard plot (Right) show the Kd between SHH-N-AP and GAS1 to be 6.1 nM. (C) (Left) Cells expressing wild-type mouse GAS1 (wt), human GAS1 (hGas1, gray), and chick GAS1 (cGas1, slashed lines) display SHH-N-AP binding. The binding was reduced after 25 ng/ml of tunicamycin treatment for 4 h (+T). Change of the first N-glycosylation site of GAS1 to A, D, or Q (N1A, N1D, and N1Q, respectively) reduced SHH-N-AP binding. (Right) N1A, N1D, N1Q, or tunicamycin-treated proteins were produced at the ≈50% level of the wt GAS1 and were detected on the cell surface by live cell labeling. Tunicamycin-treated GAS1 migrated to the same position as N1A, N1D, and N1Q (black line). GAS1 with the second predicted glycosylation site changed to a proline (N2P) behaved identically to the wild type.