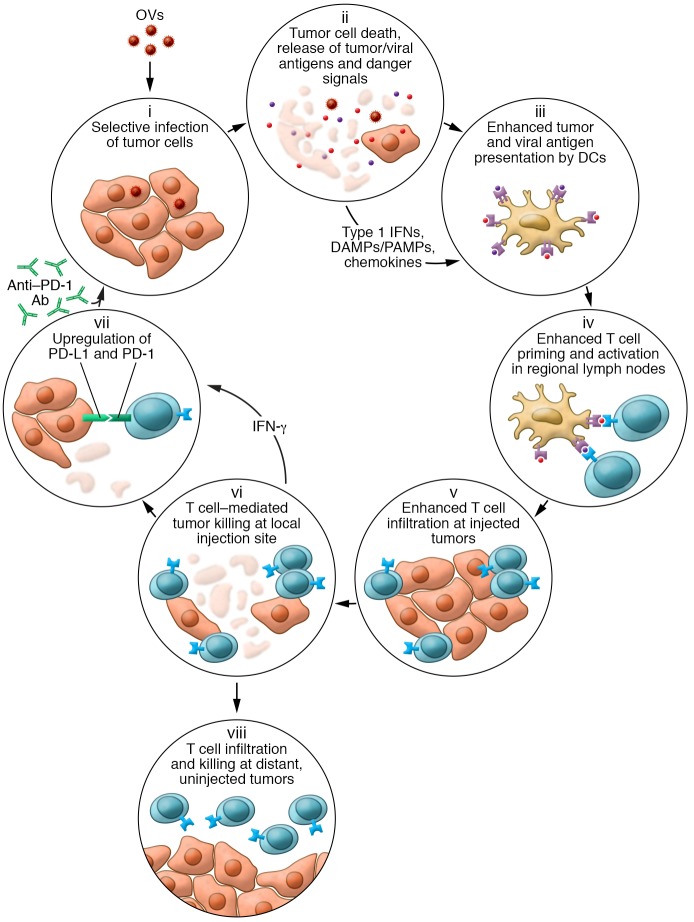

Figure 1. Schematic representation of how OVs influence various aspects of the cancer-immunity cycle.

Following tumor infection by an OV, the virus selectively replicates in tumors cells (i). The cells are lysed, resulting in immunogenic cell death and release of soluble virus- and tumor-specific antigens, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), type 1 IFNs, and chemokines (ii), which help recruit and condition professional antigen-presenting cells such as DCs (iii). DCs migrate with antigen to regional lymph nodes, where they prime and activate virus- and tumor-specific T cells (iv). The chemokine gradient generated within the tumor microenvironment recruits antigen-specific T cells (v), and T cells mediate cytotoxic effector functions within the injected tumor (vi). The local cytokine profile can also increase PD-1 expression on T cells and PD-L1 expression on tumor cells (vii) as a counterregulatory measure, limiting immune responses but also rendering the tumors more susceptible to treatment with checkpoint blockade. In contrast to some intratumoral therapies, OVs can also result in trafficking of tumor-specific T cells to distant, uninjected tumors, where they can mediate antitumor activity (viii).