Abstract

Objectives

Evaluate the reliability of using diagnosis codes and prescription data to identify the timing of symptomatic onset, cognitive assessment and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) among patients diagnosed with AD.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). The study cohort consisted of a random sample of 50 patients with first AD diagnosis in 2010–2013. Additionally, patients were required to have a valid text-field code and a hospital episode or a referral in the 3 years before the first AD diagnosis. The earliest indications of cognitive impairment, cognitive assessment and AD diagnosis were identified using two approaches: (1) using an algorithm based on diagnostic codes and prescription drug information and (2) using information compiled from manual review of both text-based and coded data. The reliability of the code-based algorithm for identifying the earliest dates of the three measures described earlier was evaluated relative to the comprehensive second approach. Additionally, common cognitive assessments (with and without results) were described for both approaches.

Results

The two approaches identified the same first dates of cognitive symptoms in 33 (66%) of the 50 patients, first cognitive assessment in 29 (58%) patients and first AD diagnosis in 43 (86%) patients. Allowing for the dates from the two approaches to be within 30 days, the code-based algorithm’s success rates increased to 74%, 70% and 94%, respectively. Mini-Mental State Examination was the most commonly observed cognitive assessment in both approaches; however, of the 53 tests performed, only 19 results were observed in the coded data.

Conclusions

The code-based algorithm shows promise for identifying the first AD diagnosis. However, the reliability of using coded data to identify earliest indications of cognitive impairment and cognitive assessments is questionable. Additionally, CPRD is not a recommended data source to identify results of cognitive assessments.

Keywords: clinical practice research datalink, medical coding, text-based data, alzheimer’s disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using enriched data elements from both structured data fields and physician notes, this study identified relevant medical codes and prescriptions related to the timing of onset of cognitive symptoms, cognitive assessments and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis, and captured an additional marker of cognitive assessment based on the sequencing of clinical interactions.

The study findings also provide important insight into the availability of results from cognitive assessments from both physician notes and coded data.

However, the study relies on Read codes and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition codes, which do not contain information by which to confirm clinical diagnoses, severity of illness or physician interpretation, and does not include data from memory clinics, a key setting in which cognitive assessments are conducted in England.

Additionally, the study focuses on patients with AD who had no evidence of other dementia aetiologies.

Finally, the study uses data prior to 2014, so study findings may not reflect the current practices in the management of patients with dementia in England.

Background

The Alzheimer’s Society of the UK estimates that approximately 1% of the entire UK population currently has some form of dementia.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for approximately 62% of all dementias in the UK. The pathophysiological changes underlying AD may develop well before a formal diagnosis, resulting in early symptoms of cognitive impairment such as memory loss, attention deficits, impaired reasoning, poor judgement and confusion prior to the diagnosis.2 3 4 5

The diagnosis of AD can be challenging, and requires the assessment of multiple domains related to patients’ cognition and function.6 Some guidelines suggest the evaluation of behavioural symptoms as well.7 Recent policy efforts in England have aimed to improve diagnosis rate and management of dementia8; as earlier, more accurate evaluation and diagnosis is believed to be important to improving potential health outcomes for patients and their caregivers as well as reduce the burden associated with dementia.9 Information about the use of and results from various evaluation tools—including tools for initial assessment (mainly in the primary care setting) such as the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG), the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS), Six-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT), and those used to inform a diagnosis (mainly in the secondary care settings) such as the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Assessment—Revised (ACE-R), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)10 11—can provide important insight regarding practice patterns during the screening and diagnostic process as well as severity of symptoms of cognitive impairment. However, this information may often not be captured in existing, structured, real-world data sources used to conduct observational studies.12 In addition, early symptoms associated with cognitive decline, such as mild memory impairment, might only be noted in free-text fields that summarise physicians’ notes and/or correspondence provided by specialists evaluating these patients in secondary care settings. These supplemental data elements are generally not available to researchers,12 which limits the ability to identify the timing of onset of symptoms and subsequent cognitive testing.

In addition, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has evaluated whether the information captured within these supplemental text data fields provides any additional insight over the coded data (eg, diagnosis codes) into the timing of onset of cognitive impairment symptoms and subsequent testing among patients eventually diagnosed with AD. Previous studies assessing the reliability of coded data (including but not limited to dementia diagnoses) typically relied on reviews of medical records, physician surveys and comparisons to other data sources.13 The objective of the present exploratory study was to assess the reliability of using a code-based algorithm to identify the timing of symptomatic onset, cognitive assessment (including initial screening) and formal diagnosis of AD, as compared with the combination of codes and supplemental, non-structured physicians’ notes and secondary care correspondence, among patients diagnosed with AD. An additional objective was to compare the availability of results from the cognitive assessments prior to AD diagnosis between the structured data and the anonymised text data.

Methods

Data

The study was conducted using a subset of the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which includes longitudinal observational data from general practitioner (GP) electronic health record systems in primary care practices, including medical diagnoses (using Read codes), referrals to specialists and to secondary care, testing and interventional procedures conducted in primary care, lifestyle information (eg, smoking, exercise) and drugs prescribed in primary care.12 The subset consisted of patients in the CPRD with a link to hospitalisations and outpatient encounters in the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset.

Until recently (May 2015), the CPRD database also included pseudoanonymised text fields summarising notes entered by the GP or providers during consultations, which were made available to researchers on special request.13 In addition, it is possible to request deidentified secondary care correspondence received by the GPs. These correspondences provide supplemental information regarding the patient’s encounters in secondary care settings such as hospitals.

Sample selection

The population for this pilot study was selected in two steps. In step 1, a cohort of patients with the earliest indication of AD in 2010–2013, who were eligible for linkage to HES and were continuously enrolled in active CPRD practice for ≥12 months before the first AD diagnosis, were selected. Indication of AD was defined as the first Read code or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) code for AD (see online supplementary appendix table 1 for details). Patients were required to have no records with diagnosis of other types of dementia (eg, vascular dementia) between or after the two most recent records indicating AD.

bmjopen-2017-019684supp001.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)

In order to ensure that the cohort of patients with AD had at least one encounter where all data elements, including physician notes and correspondence from secondary care settings, may be available, all patients were required to have ≥1 consultation record with a non-missing, non-zero text identifier and ≥1 HES record or ≥1 referral record indicating a visit to a specialist (eg, psychiatrist, neurologist, geriatrician) in the 3 years prior to the first AD diagnosis.

To facilitate detailed examination of linked free-text information, a sample of 50 patients was randomly drawn (using a computer-generated randomisation algorithm) from the cohort meeting the criteria in step 1 for further analysis. In particular, using the SAS software, all patients were assigned a random number. Following this, the first 50 patients with the smallest values for the randomly assigned numbers were selected from the dataset. A random sampling approach was used to increase the likelihood that the subsample selected was representative of the overall cohort identified in step 1.

Development of the code-based algorithm

Earliest indications of symptoms of cognitive decline (eg, ‘memory loss symptom’), cognitive assessment (for either screening or diagnosis) and AD diagnosis were identified using two parallel approaches. In the first approach, the Read codes, ICD-10 codes and prescription medications indicated to treat AD (ie, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine) found in the structured part of CPRD from up to 3 years prior to the AD diagnosis were reviewed and categorised into an algorithm to establish first observed dates of the three key time points in the pathway of progression from the onset of symptoms to AD diagnosis.

In the second approach, in addition to the diagnosis codes, a targeted search of the pseudoanonymised text data and additional correspondence provided by the GPs was conducted to identify key phrases suggestive of the earliest markers of symptoms related to cognitive impairment (eg, ‘memory loss’, ‘cognitive impairment’, ‘confusion’, etc, and their variants), cognitive assessments (eg, ‘GPCOG’, ‘MMSE’, ‘MOCA’, ‘mini-mental’, etc, and their variants) and AD diagnosis (see online supplementary appendix table 2 for a list of all phrases identified from this process). The targeted search was conducted by two independent reviewers to account for any subjective interpretation of the free text.

Based on preliminary data inspection and the combined manual review of the text and structured data for 15 of the 50 patients, the definition of cognitive assessment using the structured data was refined to include an additional marker based on referrals. Specifically, given that the clinical evaluation for dementia is usually undertaken by secondary care mental health specialists (eg, geriatricians, old age psychiatrists, neurologists)14 several weeks after the initial referral,8 it was determined that a combination of codes indicating referral to a specialist and a letter from the specialist within 3 months after the referral could be considered as indication of cognitive assessment. In addition, it was assumed that the earliest indication of cognitive assessment could not precede the earliest symptom of cognitive impairment.

Online supplementary appendix table 3 describes the final code-based algorithm used for quality evaluation.

Quality evaluation of the reliability of the code-based algorithm

The findings from the two approaches were compared to quantify the differences in dates for the first indicators of cognitive/functional symptoms, assessments and AD diagnosis as identified by the code-based algorithm and manual review. Additionally, the per cent of patients for whom the dates of each of the three measures (indicator for cognitive impairment symptoms, cognitive assessments and AD diagnosis) identified by the code-based algorithm were after the dates suggested by the second approach (suggesting the code-based algorithm was less sensitive) were calculated. Similarly, the proportions of patients for whom the dates of the three measures as identified by the code-based algorithm were before the dates identified by the second approach (suggesting the code-based algorithm was more sensitive) were reported. While exact matches were preferred for all analyses, in order to account for delays between the receipt of a letter from the specialist assessing the patient and the corresponding coding of the information in CPRD, a similar metric allowing for a 30-day gap between the dates identified by the two approaches was also measured. Note that for the purpose of the analysis, if an event was not observed for both approaches, it was considered an exact match. However, if a date was identified only in the manual review and not in the code-based algorithm, then the code-based algorithm was considered less sensitive. Similarly, if a date was identified in the code-based algorithm but not in manual review, the code-based algorithm was considered more sensitive.

Additionally, the days between the dates of first symptom of cognitive impairment and first cognitive assessment, and between the first cognitive assessment and the first AD diagnosis were compared for the two approaches. Congruence between the two data sources with regards to recording the type of and results from the specific type of the cognitive assessments performed prior to AD diagnosis was described.

The study approach is illustrated in online supplementary appendix figure 1.

Results

Sample characteristics

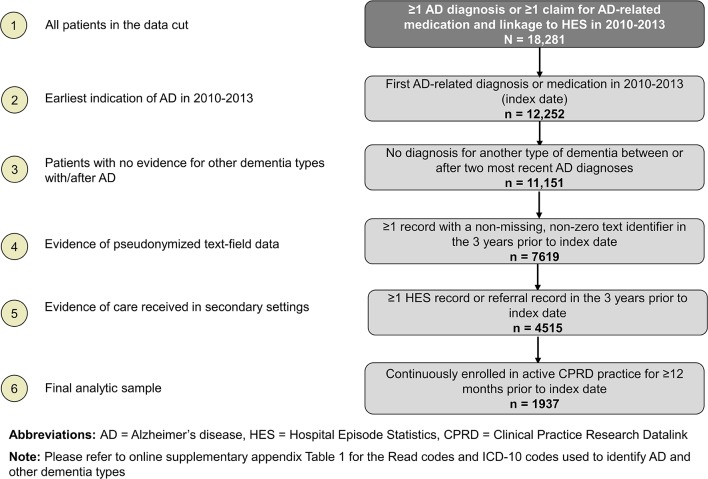

Overall, 18 281 patients in the CPRD had an indication of AD (based on diagnosis codes or AD-related medications) in 2010–2013 (see figure 1). Of these, 12 252 (67%) patients had their first indication of AD in 2010–2013; 11 151 had no indications of another type of dementia between or after AD diagnoses. Of these 11 151 patients, 4515 (40%) patients had evidence of both text-field data and receipt of care in secondary settings in the 3 years prior to the first AD diagnosis. The final sample comprised 1937 patients who met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria (mean age 82 years, 38% men). The random sample of 50 patients (selected from the 1937 patients meeting all selection criteria) included in additional analyses had similar demographic characteristics as the 1937 patients (mean age 82 years, 42% men). These 50 patients had a total of 2051 records with valid pseudoanonymised text-field data and 44 correspondences from secondary care, provided by CPRD on request.

Figure 1.

Sample selection.

Comparison of findings from the two approaches

Of the 50 patients included in the sample, the code-based algorithm identified 48 patients with evidence of cognitive impairment prior to AD diagnosis and 42 with evidence of cognitive assessment prior to AD diagnosis. An additional two and four patients, respectively, had evidence of cognitive impairment and cognitive assessment on the same date as the AD diagnosis. The remaining four patients had no record of cognitive assessment prior to or on the same date as the AD diagnosis (online supplementary appendix figure 2). For the second, comprehensive approach which used information from all available data elements including text-based data, the numbers of patients with cognitive impairment and cognitive assessments prior to AD diagnosis were 49 and 43, respectively, and the numbers of patients with the same dates for these metrics as the AD diagnosis were 1 and 4, respectively. No record of cognitive assessment was observed prior to or on the same date as the AD diagnosis for three patients (online supplementary appendix figure 2).

With regards to the timing of the three key events, relative to the second approach, the code-based algorithm was able to identify exact matches for the first date of symptoms associated with cognitive impairment in 33 (66%) of the 50 patients, first cognitive assessment in 29 (58%) patients and first AD diagnosis in 43 (86%) patients (table 1). Allowing for matches within 30 days, the algorithm’s success rates increased to 74%, 70% and 94%, respectively, for the dates of first cognitive impairment symptom, first cognitive assessment and first AD diagnosis. For most of the remaining patients, the dates detected by the code-based algorithm were several days after the dates detected by the more comprehensive approach. There was only one patient (2% of the sample), for whom the date of first symptoms of cognitive impairment identified by the algorithm was earlier than the date identified by the second, comprehensive approach, suggesting the algorithm was more sensitive. The results were similar even after allowing for a 30-day gap in the dates identified by the two approaches. With respect to identifying the dates of first cognitive assessment, the code-based algorithm was found to be more sensitive than the comprehensive approach in eight patients (16%) based on exact matches and four patients (8%) allowing for matches within 30 days. The differences in the detection of the first date of AD diagnosis between the code-based algorithm and manual review based on either exact matches or matches within 30 days were very small.

Table 1.

Differences in dates of earliest indications of cognitive impairment, cognitive assessment and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis as identified by coded data versus comprehensive data review (n=50)

| First symptom | First cognitive assessment | AD diagnosis | |

| Date matches with manual review, n (%) | |||

| Exact matches | 33 (66.0) | 29 (58.0) | 43 (86.0) |

| Matches±30 days | 37 (74.0) | 35 (70.0) | 47 (94.0) |

| Characteristics of mismatches, n (%) | |||

| Code-based algorithm more sensitive than manual review | 1 (2.0) | 8 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Code-based algorithm more sensitive than manual review (< −30 days) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Code-based algorithm less sensitive than manual review | 16 (32.0) | 13 (26.0) | 7 (14.0) |

| Code-based algorithm less sensitive than manual review (>+30 days) | 12 (24.0) | 11 (22.0) | 3 (6.0) |

Manual review included the review of both structured data and text-based data; cases where dates were not observed by either approach (n=2 for cognitive assessment only) were considered exact matches; if the algorithm generated a date value that either preceded the equivalent date in the manual review or for which an equivalent date in the manual review as not observed, it was considered as being more sensitive than the manual review.

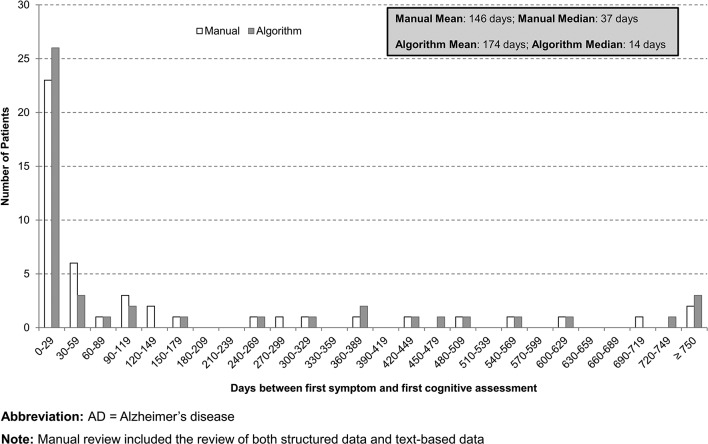

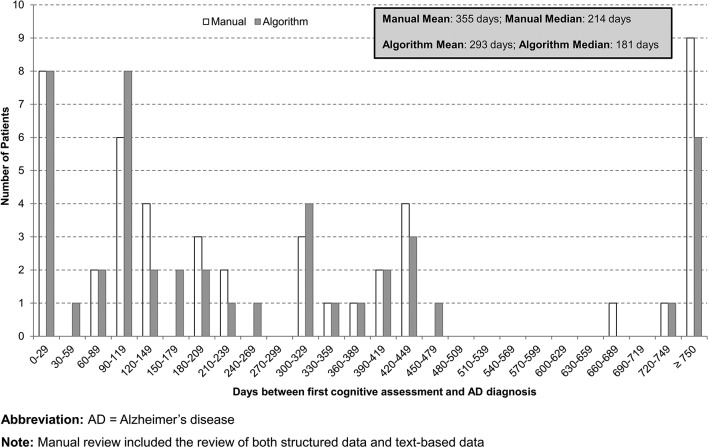

Additionally, the code-based algorithm and the comprehensive review of all data elements returned qualitatively similar gaps between the dates of first symptom of cognitive impairment and first cognitive assessment, and between the first cognitive assessment and the first AD diagnosis. For both approaches, the median time between first symptom and cognitive assessment was under 6 weeks (37 days for the manual review and 14 days for the algorithm) whereas the median time between the first cognitive assessment and the first AD diagnosis was between 6 and 7 months (214 days for the manual review and 181 days for the algorithm) (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of days between first cognitive symptom to cognitive assessment: code-based algorithm versus comprehensive data review (n=50).

Figure 3.

Distribution of days between first cognitive assessment to Alzheimer ’s disease (AD) diagnosis: code-based algorithm versus comprehensive data review (n=50).

In terms of the specific types of cognitive assessments performed prior to AD diagnosis, 34 (68%) patients had information available on the type of cognitive assessments conducted. Among these, very few patients received screening-type evaluations: three patients received the AMTS, five patients received the 6CIT and one patient received GPCOG (table 2). The more detailed evaluations captured in the data included the ACE-R (5/50 patients) and the MMSE (30/50 patients; a total of 53 assessments). A total of nine patients received multiple tests prior to AD diagnosis, primarily in addition to ≥1 MMSE assessment (table 2). For the most commonly administered cognitive assessment—the MMSE—the results were largely captured only in the supplemental (text-based) data. Specifically, 38 out of the 53 assessments had valid test scores available in the text-based data, only 6 of which were available and were consistent in both data sources. Additional 13 scores were observable only in the structured portion of the data, and neither data source reported scores for the remaining two assessments.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of cognitive assessments in the 3 years prior to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis (n=50)

| Cognitive testing characteristic | n (%) |

| Any cognitive test | 34 (68.0) |

| Type of cognitive test | |

| General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) | 1 (2.9) |

| Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) | 3 (8.8) |

| Six-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT) | 5 (14.7) |

| Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination—Revised (ACE-R) | 5 (14.7) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 30 (88.2) |

| Multiple MMSE tests | 14 (46.7) |

| Multiple tests of different types | 9 (26.5) |

| MMSE+ACE-R | 3 (33.3) |

| MMSE+AMTS | 2 (22.2) |

| MMSE+6CIT | 2 (22.2) |

| 6CIT+GPCOG | 1 (11.1) |

| MMSE+ACE-R+AMTS | 1 (11.1) |

Discussion

The results of this pilot study suggest that the information captured within the supplemental text-based data fields provides increased accuracy over the structured portion of CPRD data regarding the dates of first symptom of cognitive impairment, first cognitive assessment and first AD diagnosis, among patients diagnosed with AD. The comparison between the code-based algorithm developed in this study and a manual review of a patient’s medical history (including structured data, free text and correspondence from secondary care settings) suggests that the concordance between the two is highest for identifying the timing of the first recorded AD diagnosis, with diminishing effectiveness of the code-based algorithm in identifying the earliest records for symptoms of cognitive impairment and first cognitive assessment, respectively. Additionally, nearly two-thirds of the 50 patients included in the study had records indicative of specific types of cognitive assessments prior to or concomitantly with their AD diagnoses. For the cognitive assessment captured most commonly in the data, the MMSE, the test results were available in the text-based data for 38 of the 53 assessments, whereas the results for 13 assessments were captured only in the coded data, and the scores for the remaining two assessments were not available in either data source. This suggests that although the text-based data elements are more likely to capture this information, neither the coded data nor the additional information captured in physician notes and secondary care sources provides a comprehensive view of the detailed results of cognitive assessments. This may in part be due to the fact that much of the cognitive evaluation in England is done in specialty clinics such as memory clinics and the detailed data regarding the use of and findings from cognitive assessments may not be transferred back to the GPs. Even if the information is transferred back, it may not be entered into the system. However, given the recent initiatives to increase awareness about recognising and recording symptoms of cognitive decline within the GP setting in England (especially in populations at increased risk for dementia),8 11 and improve care coordination as well as documentation across different provider settings,15 16 the quality and completeness of data recording are likely to improve in the future, which could increase the reliability of the code-based algorithm. The improved quality of the recorded data would also facilitate identification of symptoms of cognitive impairment sooner, and facilitate real-world research into implications of earlier identification of cognitive impairment on subsequent outcomes in the UK.

Study strengths and limitations

The study used data from both the structured portion of CPRD and the text fields reflecting rich, additional information from notes captured by physicians/specialists during consultation. Using these enriched data elements, this study developed a code-based algorithm based on the findings from an intensive manual review process independently conducted by two reviewers. In doing so, we identified relevant medical codes and prescriptions to identify timing of onset of cognitive symptoms, cognitive assessments and AD diagnosis, and captured an additional marker of cognitive assessment based on the sequencing of clinical interactions. In addition, the study provides important insight into the availability of results from cognitive assessments, in particular MMSE, from both physician notes and coded data.

However, this study also has a number of limitations. First, the study relies on the Read codes (primary care) and ICD-10 codes (secondary care) used within the CPRD and HES administrative records datasets, respectively. These codes are retrieved from electronic health records and hospital admission records and do not contain information by which to confirm clinical diagnoses, severity of illness or physician interpretation. Accordingly, it is possible that some patients identified as having been diagnosed with AD, with no recorded diagnosis of other type, have other dementia aetiologies instead.17 Relatedly, the earliest marker of onset of cognitive symptoms is based on the information captured in the data, and the precise timing of perceived onset of cognitive impairment is not known. In addition, for this study, though we reviewed the correspondence from some secondary care interactions, we did not have access to data from memory clinics, which is a key setting in which cognitive assessments are conducted in England. Future research should identify avenues to compare the reliability of the algorithm relative to data captured in these settings as well. This study is also limited in sample size, as the algorithm was only developed and assessed for 50 randomly selected patients who were diagnosed with AD. In addition, the algorithm may not capture all Read codes and ICD-10 codes indicative of symptoms of cognitive impairment, cognitive assessment and AD diagnosis. As such, additional research using larger patient populations is necessary to further test the reliability and generalisability of the algorithm. Furthermore, the study was focused on patients with AD who had no evidence of other dementia aetiologies, and further research is needed to assess the reliability of the coded data for identifying the timing of cognitive impairment, cognitive assessment and diagnosis among patients with other dementia aetiologies. Finally, the study used data prior to 2014 and the study findings may not reflect the current practices in the management of patients with dementia in England.

Conclusions

Given the limited expected future availability of free-text data and secondary care correspondence in CPRD, the code-based algorithm developed using data for a small sample of patients with AD shows promise as a reliable alternative for identifying the earliest indications of AD. However, the reliability of using coded data to identify earliest symptoms of cognitive impairment as well as indications of cognitive assessments prior to AD diagnosis is limited. The use of coded data, in its present form, is not recommended for identifying information regarding the specific types of cognitive assessments performed, the specialty of physicians performing the assessments or the results associated with those assessments (eg, to assess disease severity levels).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NYK, UD, GD, CCR and MB contributed to the conceptual design and reviewed and discussed the study results. JW and MKM contributed to the conceptual design and performed data analysis. AL-S, JR and CM contributed in the interpretation of study findings. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Competing interests: GD, CCR, MB and AL-S are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company. NYK, UD, JW and MKM are employees of Analysis Group, a company that received funding from Eli Lilly and Company for this research. CM and JR are consultants to Eli Lilly and Company.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol no: 16_043R).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This study used the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, provided by CPRD. Per the data use agreement, the datasets supporting the conclusions of this article cannot be made available to researchers outside of the study team. However, interested readers may request the data directly from CPRD—see for more information.

References

- 1. Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia UK: Update. 2014. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=2323 (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 2. Mortimer JA, Borenstein AR, Gosche KM, et al. . Very early detection of Alzheimer neuropathology and the role of brain reserve in modifying its clinical expression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2005;18:218–23. 10.1177/0891988705281869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. . Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:119–28. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petersen RC. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: is MCI too late? Curr Alzheimer Res 2009;6:324–30. 10.2174/156720509788929237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. . The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute of Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NHS Choices. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Alzheimers-disease/Pages/Diagnosis.aspx (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 7. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. 2007. https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/topics/diagnosis#how (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 8. Government of UK. Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prime-ministers-challenge-on-dementia-2020/prime-ministers-challenge-on-dementia-2020 (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 9. Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, et al. . Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review on benefits and challenges. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;49:617–31. 10.3233/JAD-150692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NHS Department of Health. Dementia revealed: what primary care needs to know. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/dementia-revealed-toolkit.pdf (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 11. NHS England. Dementia diagnosis and management: a brief pragmatic resource for general practitioners. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/dementia-diag-mng-ab-pt.pdf (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 12. Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. . Data resource profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:827–36. 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the general practice research database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:128–36. 10.3399/bjgp10X483562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alzheimer’s Society UK. Assessment process and tests. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/info/20071/diagnosis/95/assessment_process_and_tests/2 (accessed 6 Feb 2017).

- 15. The King’s Fund. Transforming our healthcare system: ten priorities for commissioners. 2015. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/10PrioritiesFinal2.pdf (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 16. NHS National Information Board. Personalized health and care 2020: using data and technology to transform outcomes for patients and citizens. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/384650/NIB_Report.pdf (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 17. Happich M, Kirson NY, Desai U, et al. . Excess costs associated with possible misdiagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease among patients with vascular dementia in a UK CPRD population. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;53:171–83. 10.3233/JAD-150685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019684supp001.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)