Abstract

Objective

Although evidence-based treatments for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) exist, many youth fail to respond, and interventions tailored to the needs of specific subsets of patients are lacking. This study examines the efficacy of a family intervention module designed for cases of OCD complicated by poor family functioning.

Method

Participants were 62 youngsters ages 8–17 (mean age = 12.71 years; 57% male; 65% Caucasian) with a primary diagnosis of OCD and at least two indicators of poor family functioning. They were randomized to receive 12 sessions of individual child cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) plus weekly parent psychoeducation and session review (standard treatment; ST) or the same 12 child sessions plus six sessions of family therapy aimed at improving OCD-related emotion regulation and problem-solving (Positive Family Interaction Therapy; PFIT). Blind raters evaluated outcomes and tracked responders to three-month follow-up.

Results

Compared to ST, PFIT demonstrated better overall response rates on the Clinician Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I; 68% versus 40%, p = .03, phi = 0.28) and rates of remission (58% PFIT versus 27% ST, p = .01, phi = 0.32). PFIT also produced significantly greater reductions in functional impairment, symptom accommodation, and family conflict, and improvements in family cohesion. As expected, these shifts in family functioning constitute an important treatment mechanism, with changes in accommodation mediating treatment response.

Conclusion

PFIT is efficacious for reducing OCD symptom severity and impairment and for improving family functioning. Findings are discussed in terms of personalized medicine and mechanisms of change in pediatric OCD treatment.

Clinical trial registration information

Family Focused Treatment of Pediatric Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; http://clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT01409642.

Keywords: Pediatric OCD, CBT, family treatment, exposure

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic, impairing condition that confers significant concurrent and long-term risk to affected youth.1,2,3 Although both cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacological interventions have proven efficacious for reducing symptoms,4,5 many youth fail or only partially respond to treatment. Indeed, controlled treatment trials find that only about 40% of youth demonstrate excellent response to CBT, the current frontline intervention for pediatric OCD5,6; half that number exhibit similar response to medication. Indeed, even with combined intervention (CBT + sertraline), nearly 50% of participants remain symptomatic following treatment.6 These findings are sobering, and they underscore the need for continued work aimed at improving clinical response in pediatric OCD.

Factors such as baseline symptom severity, comorbidity, and family functioning have been identified as important determinants of response.7–9 Of these, family factors may be particularly important given the central role that parents play in helping youth adhere to treatment and maintain gains over time. Ample literature documents that disrupted family functioning is common in pediatric OCD.3,10 Distress is the norm, and it is often accompanied by blame, hostility, and poor cohesion.11–13 Family conflict and symptom accommodation (i.e., assistance with/participation in rituals) are noted frequently, and the pervasiveness of both features12,14,15 makes it likely that they will occur within the same family.

To date, most work on familial correlates of pediatric OCD has centered on accommodation,15–17 finding that it mediates the link between symptom severity and functional impairment,14 and that it predicts CBT outcome.7,8,18 Perhaps more importantly, changes in accommodation appear to precede symptom improvement for children, adolescents, and adults with OCD.19,20 Together, these findings point to the importance of addressing accommodation in treatment.

Yet, accommodation can be strikingly difficult to change. It often occurs alongside other family dynamics, which may make efforts to disengage from symptoms less successful and may attenuate treatment response themselves.21 Features such as blame and criticism are well documented among families of both children and adults with OCD,22 and they predict poorer CBT response for both groups.12,22,23 Recent research examining the additive effects of poor family functioning on treatment outcome found that youth from families characterized by high levels of blame, conflict, and poor cohesion demonstrated only a 10% response to family-focused CBT for OCD, while youth in homes with no problems in these domains demonstrated a 93% response rate.12 These findings point to the need to look beyond symptom accommodation to broader family dynamics that may interfere in pediatric OCD treatment.

The importance of family involvement in OCD treatment is well-recognized. For over a decade, it has been recommended as an adjunct to individual child treatment based on expert consensus and reviews of the literature.4,5 Indeed, nearly every child treatment involves some degree of parental participation. With limited exception, however, current family interventions have failed either to shift familial beliefs and behaviors or to produce meaningful changes in family functioning.4 Although the reasons are not entirely clear, current family interventions may not focus sharply enough on the most relevant variables, or they may fail to target these variables with sufficient intensity. For example, most protocols that address family accommodation do so through psychoeducation and general behavior management techniques, approaches that are likely to work well for relatively intact families, but that may fall short in families characterized by poor distress tolerance or heightened conflict. Indeed, research suggests that families characterized by high levels of conflict and blame report more difficulty when they attempt to disengage from OCD symptoms; by contrast, families that describe themselves as high in cohesion appear to have more success.21 Given the frequency with which compromised family functioning is reported in pediatric OCD, interventions tailored to the needs of this subgroup remain a priority.

To address this need, we developed Positive Family Interaction Therapy (PFIT),24 a six-session module designed to be used as an adjunct to individual child CBT in cases of pediatric OCD complicated by poor family functioning. PFIT integrates aspects of traditional psychoeducation and parent training but moves beyond current protocols in its emphasis on emotion regulation skills training and distress tolerance; functional analysis of the role of symptoms in the family context; and collaborative problem-solving. These skills are thought to be central to helping highly distressed families navigate the demands of exposure-based treatment. In a pilot feasibility trial, PFIT demonstrated adequate acceptability and tolerability, with high levels of patient satisfaction and family participation.25

The present investigation was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the efficacy of PFIT for reducing OCD symptoms among youth in highly distressed homes. Recognizing that several treatments already exist for the typical youngster with OCD,19,26,27 and that a novel intervention would need to demonstrate unique benefit, PFIT was compared to the current frontline intervention (standard treatment; ST), which was comprised of individual child exposure-based CBT, plus weekly family psychoeducation, check in, and detailed review of session. Given that PFIT targets specific family dynamics likely to interfere with treatment, and that youth in the study were selected on the basis of both OCD and poor family functioning, we hypothesized that PFIT would prove superior to ST in reducing OCD symptom severity, related functional impairment, and family accommodation. Moreover, because PFIT addresses features that may hinder families’ disengagement from symptom involvement, we hypothesized that changes in accommodation would mediate treatment outcome.

METHOD

Study Design

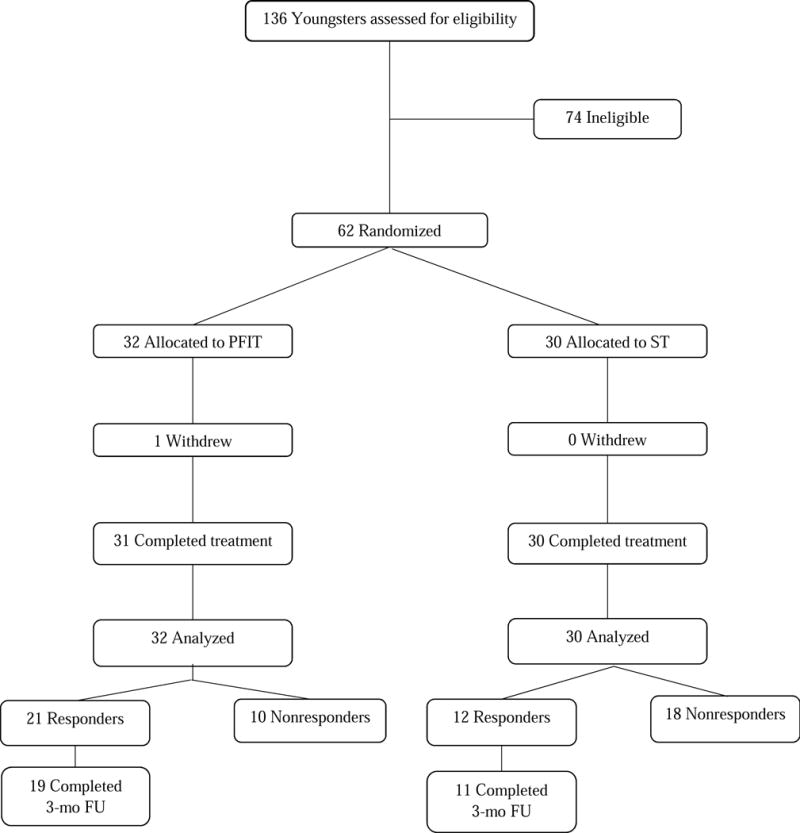

The study was approved by the university institutional review board and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01409642). A total of 62 youth were assigned to either PFIT or ST (see Figure 1) in a 1:1 ratio using a computerized block-randomization algorithm. All youth received 12 sessions of individual exposure-based CBT and the same amount of family intervention time. However, the content and structure of the family intervention differed, with PFIT families meeting every other week for one hour of joint therapy and ST families participating in 30-minute meetings at the end of each child session. Independent evaluators (IEs) blind to study condition completed assessments at mid-treatment and posttreatment. Responders in both conditions were assessed at 3-month follow-up to examine maintenance of gains. Acute-treatment non-responders were given appropriate clinical referrals and did not complete the follow-up assessment.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram Study enrollment and retention. Note: PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy, ST = Standard Treatment, FU = Follow-up.

Participants

Youth ages 8 to 17 years and their families were recruited via referrals from a pediatric OCD specialty clinic in an urban medical center setting and from the community. As PFIT was designed specifically for cases of OCD complicated by poor family functioning, eligibility was determined based on both diagnostic and family criteria: (a) a primary DSM-IV-TR28 diagnosis of OCD; (b) a score of 15 or higher on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)29; (c) at least two indicators of poor family functioning on measures previously shown to predict diminished response to CBT for OCD. Elevations on these measures were determined using previously established cut-points; (d) no prior history of receiving CBT for OCD; (e) a parent who could speak sufficient English to participate in family therapy; (f) no comorbid psychiatric illness for which study participation was contraindicated (e.g., schizophrenia, substance dependence); other co-primary (e.g., anxiety, major depressive disorder [MDD]) and secondary diagnoses were permitted. Youth on a stable dose of psychotropic medication were included provided they were comfortable refraining from changes during the course of the trial.

Procedures

Interested families completed a telephone screen; those who appeared to be eligible were invited to the clinic to complete informed consent/assent and the baseline evaluation. Diagnostic and symptom severity interviews were administered jointly to parents and children by IEs along with assessments of family accommodation. Families also completed a standardized battery of self-report measures, including assessments of family functioning, as well as other lab tasks.

Following the baseline assessment, eligible participants were randomly assigned to either PFIT or SEBT. To minimize therapist-specific confounds, clinician assignment was balanced over time so that each therapist treated participants in both conditions.

Treatment Conditions

Standard Treatment (ST)

The comparison treatment was designed to reflect current best practices5 and involved an existing 12-session treatment manual for pediatric OCD.30 The first 60 minutes of each session were devoted to exposure and response prevention (ERP) and cognitive restructuring with the child; the remaining 30 minutes were family-focused. Following an approach validated in previous work,19,31 each week covered a different topic including causes and prevalence of OCD; the rationale for ERP; the importance of disengaging from symptoms; and the range of emotional responses to OCD. In addition to psychoeducation, parents received a detailed review of the child session and what was assigned for homework, and they had an opportunity to ask questions. ST therapists were allowed to encourage parents to attempt to refrain from accommodation; however, the original manual was modified such that they did not provide any specific guidance on how to do this, and no behavior management techniques were taught.

Positive Family Interaction Therapy (PFIT)

Youth in the PFIT condition participated in the same 12 sessions of individual child ERP. However, the weekly 30-minute family component was replaced with one hour of family therapy every other week. PFIT24 is a tailored module designed specifically to address familial responses to OCD that are known to attenuate treatment response (e.g., blame, conflict, poor cohesion21). In the six-session protocol, traditional psychoeducation is expanded to include more in-depth focus on the role of the family in OCD. This includes understanding various forms of symptom accommodation, their role in perpetuating symptoms, and barriers to disengaging from symptom involvement. In addition, families are taught to attend to and monitor their own emotional responses to OCD and to practice corresponding emotion regulation and problem-solving skills. This includes functional analysis of difficult family situations related to OCD, practice with negotiating effective solutions, and weekly exercises to promote supportiveness, collaboration, and cohesion. Throughout the protocol, there is a strong emphasis on applied skills practice to improve distress tolerance, disengagement from accommodation, joint problem solving, and scaffolding. Importantly, the PFIT intervention is designed to be administered flexibly; sessions can be frontloaded or clustered as needed to meet individual patient needs.

Therapist Training, Supervision, and Fidelity

Treatment was provided by licensed clinical psychologists and by advanced psychology doctoral students who underwent extensive training in the study interventions. Training began with didactics and review of treatment manuals to ensure clear understanding of treatment principles and study procedures. Therapists progressed to viewing session tapes and to co-leading a case with the first author before being certified to treat participants independently. Ongoing weekly supervision was provided by either the first or last author. Investigator allegiance effects were protected against by having the developers of both the target and comparison interventions provide supervision in both study arms, and specific efforts were made to prevent carryover between treatments. All therapy sessions were videotaped; 10% of PFIT sessions (n=18), distributed evenly across the protocol, were assessed for adherence (range 0–100) and overall quality (range 1–10) using forms developed during initial pilot testing of the protocol. Ratings indicated good adherence (mean= 93.77; SD=5.75) and treatment quality (mean=9.22; SD=.73). In addition, 10% of the weekly ST family sessions (n=38) were also evaluated for adherence (using forms developed in the original randomized controlled trial [RCT] for that treatment), overall quality, and potential overlap with PFIT intervention components. These ratings suggested excellent adherence (mean= 91.67; SD=7.25) and treatment quality (Mean= 9.42; SD=.77) with minimal overlap (mean =.43; SD=.54).

Measures

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule: Child and Parent Version (ADIS-C/P)

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule: Child and Parent Version (ADIS-C/P),32 is a semi-structured psychiatric diagnostic interview with excellent psychometric properties33 that was used to determine study eligibility. Although we did not conduct a formal reliability assessment, studies from our program utilizing similar training and supervision procedures have demonstrated excellent agreement on OCD diagnosis (k = .89) between diagnosticians and a best-estimate derived from a consensus case conference procedure.19

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)29 is a clinician-rated interview consisting of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The total severity score was used to assess symptomatology. The CY-BOCS possesses adequate internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity.34 The present sample yielded inter-rater reliability intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)= .98 and Cronbach’s α = .63 for the total score at baseline.

Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R)

Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R)35 is designed to assess OCD-specific functional impairment. It is comprised of 33 items on a 4-point Likert scale, and possesses acceptable psychometric properties. Cronbach’s α = .88 for mother and .91 for father at baseline.

Family Accommodation Scale (FAS)

Family Accommodation Scale (FAS)36 is a 13-item interview with well-established psychometric properties35 that was administered by IEs to assess the degree of family accommodation over the preceding month. It measures both behavioral involvement in symptoms (e.g., participation in rituals) and the level of family distress associated with this involvement. Baseline Cronbach’s α = .84.

Family Environment Scale (FES)

Family Environment Scale (FES).37 The FES is a 90-item self-report measure assessing multiple domains of family functioning. Parents completed two subscales: Cohesion, the degree to which family members support each other, and Conflict, a measure of overt discord. Baseline α’s for mother and father, respectively, were .68 and .55 for Cohesion and .61 and .75 for Conflict.

Parental Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (PABS)

Parental Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (PABS)11 is a 24-item parent-report measure with good concurrent and predictive validity,11 comprising three subscales: Blame, Accommodation, and Empowerment. The Blame scale (9 items) was used in the present investigation. Baseline Cronbach’s α = .87 for mother and .86 for father.

Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale (CGI-I)

Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale (CGI-I)38 is an IE-rated measure of overall improvement from baseline. Scores range from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse), with youth rated as 1 or 2 (much improved) considered treatment responders.

Interviewer Training and Reliability

All IEs were masters- and doctoral-level clinicians, trained to criterion according to procedures established by the instrument developers. Training included a systematic sequence of didactics, observation/co-rating of expert clinicians, and live supervision until reliability was achieved. Ongoing weekly supervision was provided by licensed clinical psychologists with specialty training in pediatric OCD. IEs were blind to treatment assignment and study hypotheses, and the blind was preserved via multiple established procedures, including reminders to families not to disclose the specifics of their particular family treatment during assessments. Independent review of 20% of posttreatment CGI-I ratings revealed excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC=.90).

Analytic Approach

The success of randomization was checked using chi-square and t-tests; there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. Chi-square tests were also used to check for differences in the rates of treatment response (primary outcome = CGI-I ≤ 2) and OCD remission (secondary outcome = CYBOCS ≤ 14 at posttreatment26). Mixed models effects with group (PFIT, ST), time (pre-, post-treatment), and a group × time interaction were used to test for differential treatment response on continuous secondary clinical (CYBOCS; COIS-R) and family (FES cohesion and conflict, FAS, and PABS) outcomes. Mixed models account for the correlations induced by repeated measurements within participants and automatically handle missing data, producing unbiased estimates as long as observations are missing at random. Specifically, our models used unstructured covariance matrices to account for within-subject effects and were fit via restricted maximum likelihood. Estimated marginal means and post hoc contrasts were used to characterize the longitudinal patterns of effects corresponding to significant interactions. For secondary parental report outcomes, following the approach of prior studies,39–42 the mean of mother and father responses was used whenever available. The primary analyses were intent-to-treat, using all available data from each randomized participant, regardless of degree of participation. Those who dropped out or whose study participation was prematurely terminated due to symptom worsening were contacted for follow-up assessments, and those observations were included in the analyses if available.

To examine whether initial gains were maintained 3-months post treatment, an additional set of mixed models was run with treatment responders only, as non-responders did not complete the follow-up assessment. Models included group (PFIT, ST) and time (baseline, posttreatment, 3-month follow-up). Specific contrasts from baseline to follow-up, and posttreatment to follow-up were tested, as we were interested in both whether responders remained improved at follow-up relative to baseline, as well as potential deterioration from posttreatment to follow-up. Exploratory mediation analyses examined whether changes in family accommodation accounted for treatment response. Specifically, we calculated the direct effects of treatment group on FAS change from pre- to posttreatment (proposed mediator) and treatment responder status (outcome), as well as the effect of treatment on response after adjusting for FAS change. We then used a bootstrap procedure (Hayes, 2009), implemented in the SPSS PROCESS macro, to calculate a 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect of treatment on change in symptom severity via its effect on accommodation.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

The intent-to-treat sample included 62 participants. Their mean age was 12.71 years (SD = 2.76 years; range 8–17 years), and 57% were male. The sample had considerable racial/ethnic diversity, with 65% identifying as Caucasian, 13% Hispanic/Latino, 7% Asian, 5% Iranian, 3% African American, and 7% reporting mixed racial/ethnic background. Most participants (83.9%) came from intact homes. At baseline, 23% were taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and 2% were taking stimulants. Study participants were clinically complex, with 61% meeting criteria for at least one comorbid diagnosis. There were no significant differences between treatment groups at baseline (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Overall and by Arma

| Full Sample (N=62) |

PFIT (n=32) |

ST (n=30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.12 (2.68) | 12.61 (2.55) | 13.66 (2.75) |

| Gender (% female) | 44% | 50% | 37% |

| Minority (%) | 29% | 28% | 30% |

| SSRI | 20% | 19% | 21% |

| CYBOCS | 25.48 (3.51) | 25.53 (3.72) | 25.43 (3.33) |

| CGI-S | 5.28 (0.80) | 5.35 (0.80) | 5.20 (0.81) |

| Comorbid diagnoses (%) | |||

| Anxiety | 45% | 47% | 43% |

| Depression | 15% | 13% | 18% |

| ADHD | 22% | 19% | 25% |

| ODD/CD | 10% | 16% | 4% |

| Chronic tic/Tourette | 12% | 13% | 11% |

| Autism spectrum | 5% | 10% | 0% |

Note. Anxiety diagnoses include separation, social, generalized, and specific phobia; depression includes major depressive disorder and dysthymia. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impression Scale – Severity; CYBOCS = Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; ST = standard evidence-based treatment; minority, ethnic and/or racial minority status.

No significant group differences on any demographic or clinical variables at baseline.

Participant Retention

Of the 62 participants, 98% (n=61) completed the posttreatment assessment (Figure 1). One participant in the PFIT arm withdrew due to symptom severity (baseline CYBOCS= 32). All others completed treatment in full and groups did not differ in time to complete treatment (p = .503). Of the posttreatment responders (n=33), 88% (n=29) completed the three-month follow-up. Responders who participated in the three-month assessment vs. those who were lost to follow-up did not differ on baseline or posttreatment variables of interest. Given our intent-to-treat framework, all available measurements on all participants were included in the relevant analyses, regardless of degree of participation.

Clinical Outcomes

Responder Status

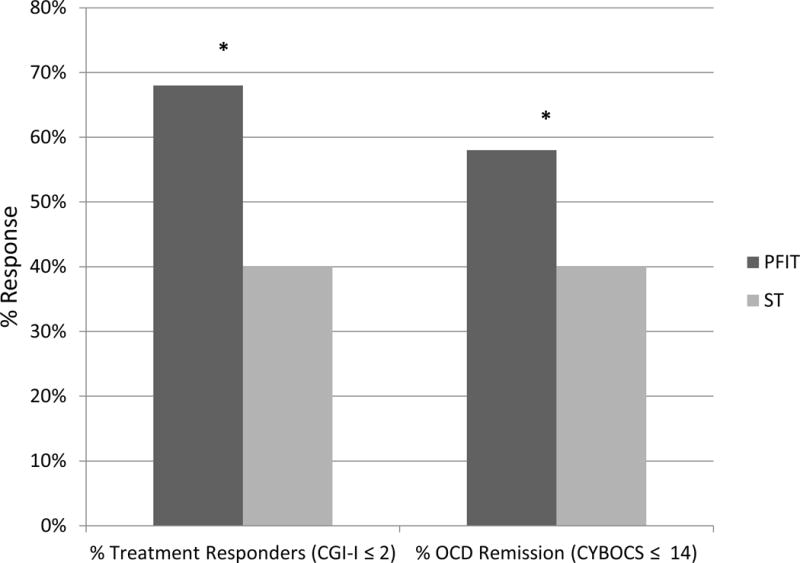

At posttreatment 68% (21/31) of PFIT youth were rated as responders on the CGI-I compared to 40% (12/30) of ST youth (χ21= 4.73, p= .03, phi= 0.28; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Treatment response and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) remission by group. Note: CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression Scale– Improvement; CYBOCS = Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy; ST = standard evidence-based treatment. * Indicates significant group differences (p < .05).

OCD Remission

At posttreatment 58% (18/31) of PFIT youth achieved remission compared to 27% (8/30) of youth receiving ST (χ21= 6.15, p= .01, phi = 0.32; Figure 2).

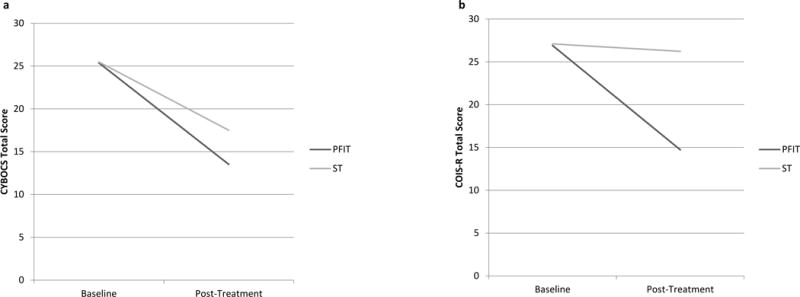

OCD Severity and Functional Impairment

In the mixed models analysis for CYBOCS total severity score, the group × time interaction approached significance (F[1, 58.72]= 3.98, p= .052). Plots of estimated marginal means (Figure 3a) and post hoc tests indicated that on average both groups demonstrated CYBOCS decreases over time (mean changes: PFIT= −11.85, SE= 1.37, p< .001; CBT= −7.97, SE= 1.39, p<.001), but that the improvement was greater in the PFIT group, which showed significantly lower CYBOCS severity scores at posttreatment than the ST group (Mean difference= −3.98, SE= 1.88, p=.038). A parallel analysis for functional impairment (COIS-R; Figure 3b) revealed a significant group × time interaction (F[1, 54.22]= 13.94, p< .001), with the PFIT group having lower COIS scores at posttreatment than the ST group (mean difference= −11.50, SE= 3.87, p= .004). Moreover, while the PFIT group demonstrated significant reduction in OCD-related impairment from pre- to posttreatment (COIS mean change = −12.19, SE= 2.18, p < .001), the ST group did not (mean change= −0.88, SE=2.11, p= .68).

Figure 3.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder severity and impairment by group from baseline to posttreatment. Note: Data presented for estimated marginal means from mixed models analysis. COIS-R = Child Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Impairment Scale – Parent-Report Revised; CYBOCS = Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy; ST = standard evidence-based treatment.

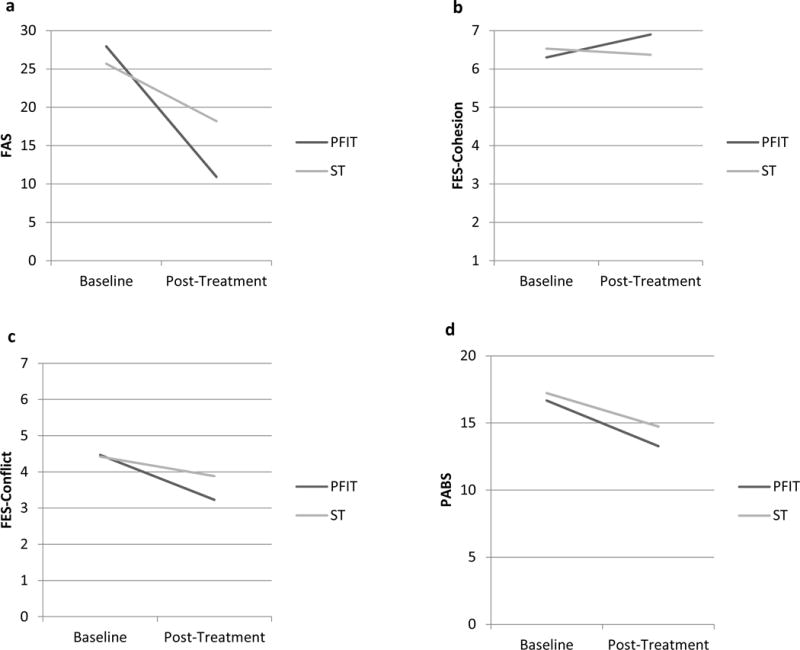

Family Functioning

To examine secondary outcomes, separate mixed models were fit for the FAS, FES conflict and cohesion subscales, and PABS. There was a significant group × time interaction on the FAS (F[1, 56.95]= 9.09, p= .004). While there were reductions for both groups over time (mean changes: PFIT= −17.02, SE= 2.20, p< .001; ST= −7.48, SE= 2.27, p= .002), the PFIT group demonstrated significantly greater decrease in OCD-related accommodation compared to SD (mean difference= −7.28, SE= 2.73, p= .01). There was also a differential treatment effect for Cohesion (interaction F[1, 57.10]= 5.03, p= .03), in which the PFIT group demonstrated a significant improvement (mean change= 0.60, SE= 0.28, p= .03), while the ST group did not (mean change= −0.23, SE= 0.27, p= .34). However, the groups did not differ significantly on parent-reported cohesion at posttreatment (mean difference= 0.63, SE= 0.39, p= .12; Figure 4b). The same pattern of effects was found for family conflict (interaction: F[1,56.65]= 4.15, p= .046; PFIT mean change= −1.26, SE= 0.37, p= .001; ST mean change = .05, SE= 0.47, p= .91; posttreatment mean difference= −0.81, SE= 0.43, p= .065; Figure 4c). Finally, the mixed model for parent-reported blame had no group or group × time interaction effects, although there was an overall reduction in blame from pre- to posttreatment (time main effect F[1, 58.38]= 24.42, p< .001; mean change= −2.95, SE= 0.60, p < .001; Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Family functioning outcomes by group from baseline to posttreatment. Note: Data presented for estimated marginal means from mixed models analysis. FAS = Family Accommodation Scale; FES = Family Environment Scale; PABS = Parental Attitudes and Behaviors Scale; PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy; ST = standard evidence-based treatment.

Three-Month Follow-Up

Clinical Outcomes and Remission Status

Week 12 treatment responders (PFIT n=21, ST n=12), as rated by a CGI-I ≤ 2, were re-contacted and 29/33 (88%) completed the three-month follow-up assessment. The groups did not differ significantly in three-month attrition rates (χ21= 0.01, p = .91, phi =0.02). Of treatment responders, 94% (16/17) of PFIT and 82% (9/11) of ST retained responder status at follow-up, with no group differences (χ21= 1.17, p= .28, phi=.20; Figure 2). For additional details on follow-up outcomes, please see Table S1, available online.

Family Functioning as Mediator of Treatment Response

Exploratory mediation analyses were conducted with treatment group (independent variable), FAS change from pre- to posttreatment (proposed mediator), and responder status (outcome). There was a direct effect of treatment on FAS change (β= 8.71, SE=3.14, t= 2.77, p= .007) and a significant direct effect of treatment on responder status (β= 1.09, SE=0.54, Z= 2.03, p= .04). The effect of treatment on responder status became fully non-significant after adjusting for FAS change (β= 0.53, SE=0.62, Z= 0.85, p= .40), and the bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect did not include zero (estimated IE= 0.88, CI= 0.13, 1.85), suggesting significant mediation.

DISCUSSION

This study tested the efficacy of the PFIT protocol for cases of pediatric OCD complicated by poor family functioning. Against a robust comparison treatment comprised of individual child ERP plus weekly family psychoeducation and session involvement, PFIT demonstrated a clear advantage in terms of overall response and remission rates, and reductions in functional impairment; improvements in symptom severity approached significance. Likewise, PFIT appeared to outperform ST on measures of family functioning, producing significantly better reductions in symptom accommodation and family conflict as well as improvements in family cohesion. As expected, these shifts in family functioning constitute an important treatment mechanism, with changes in accommodation accounting for changes in clinical symptoms.

To our knowledge, this is the first psychosocial intervention developed specifically for a subset of youth who are likely to exhibit suboptimal response to standard OCD protocols.6, 30 For these youth, it is encouraging that a 6-session, adjunctive family intervention can improve upon outcomes reported in the broader treatment literature.5 Importantly, youth in this sample who were selected on the basis of both OCD diagnosis and disrupted family functioning did not fare as well in the comparison arm, even though it offered what is widely considered state of the art intervention.5 PFIT produced better overall response rates and a two-fold greater rate of remission compared to ST, with medium effect sizes for both (phi = .28 and .30 respectively). This generally consistent pattern of findings is compelling given the high bar set by our active comparison group. Indeed, we know of no other pediatric OCD RCT employing such a robust comparison arm. Only two prior studies have used credible comparison treatments, both opting for a combination of psychoeducation and relaxation training.4,19 Our use of ERP—the active ingredient in OCD treatment—for all study youth bolsters confidence in the specific value of PFIT intervention techniques.

PFIT is also likely responsible for the improvements observed across multiple family measures. Several studies document that family functioning predicts diminished treatment response for youth with OCD.12,22 To date, however, family intervention has relied primarily on psychoeducation and global behavioral management to address these challenges. The PFIT emphasis on emotion regulation and problem-solving skills training is novel in this area, and it may be valuable for helping parents learn to tolerate distress and to troubleshoot difficult OCD episodes successfully. Certainly, PFIT families demonstrated significant improvements in accommodation, conflict, and cohesion compared to their counterparts in ST. Differences in blame reduction were not observed across groups, indicating that systematic psychoeducation may be sufficient to change attributions of control and responsibility related to the disorder.

Importantly, this study identifies reductions in accommodation as a potential mechanism of change in pediatric OCD treatment. Although well-documented as a predictor of clinical response,7,8,18 no previous study has demonstrated that changes in symptom accommodation account for clinical improvement for youth receiving CBT for OCD. This finding builds on work indicating that changes in accommodation precede symptom improvement,19 and it underscores the value of working with families to change patterns of responding to OCD. The overall success of PFIT in improving family functioning suggests that addressing broader dynamics as part of this process may be important to help them meet the demands of treatment.

Certainly, these findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. Although powered to address primary aims, the sample is small, precluding more rigorous tests of putative mechanisms. Likewise, the follow-up period is relatively brief, leaving unanswered questions regarding treatment durability. In addition, although our use of an active and well-established comparison treatment gave study participants two potent intervention options, data on parent and child treatment expectations/credibility are lacking, as are data on parental psychopathology. We also note that while the IE blind was vigorously protected, therapists themselves were not blind to study hypotheses. Finally, both treatments in this study were administered by clinical trainees and early career psychologists with high quality training in pediatric OCD intervention and supervised closely by experts in the field. It will be important to determine how well findings generalize to real-world community settings.

Despite these shortcomings, the present findings provide an important step forward for those who seek to personalize pediatric OCD treatment based on individual patient characteristics. They provide encouraging evidence that such an approach can improve outcomes for carefully identified subsets of youth, and they point to the need for further work aimed at identifying tailoring variables that may be used to optimize outcome for this complex condition.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Outcome Measures at Baseline and Posttreatment by Treatment Arm

| Baseline | Posttreatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PFIT | ST | PFIT | ST | |

| CGI-I | – | – | 2.16 (0.78) | 2.73 (0.98) |

| CYBOCS | 25.38 (3.86) | 25.47 (3.33) | 13.45 (7.17) | 17.50 (7.48) |

| COIS-RP | 26.91 (14.76) | 26.52 (12.90) | 13.94 (11.36) | 26.22 (17.33) |

| FAS | 27.94 (11.02) | 25.44 (8.95) | 10.81 (9.75) | 18.20 (11.57) |

| FES-Conflict | 4.47 (1.82) | 4.42 (1.89) | 3.26 (1.89) | 3.88 (1.97) |

| FES-Cohesion | 6.30 (1.76) | 6.53 (1.50) | 6.93 (1.42) | 6.27 (1.60) |

| PABS | 16.67 (5.12) | 17.23 (5.42) | 13.13 (4.60) | 14.76 (4.79) |

Note. CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression Scale – Improvement; COIS-R = Child Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Impairment Scale – Parent-Report Revised; CYBOCS = Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; FAS = Family Accommodation Scale; FES = Family Environment Scale; PABS = Parental Attitudes and Behaviors Scale; PFIT = Positive Family Interaction Therapy; ST = standard evidence-based treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants to Dr. Peris: NARSAD Young Investigator Award (Peris) and NIMH K23 MH085058 (Peris).

Dr. Sugar served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study therapists and the families who participated in this project.

Disclosure: Dr. Peris has received research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology and book royalties from Oxford University Press. Dr. Rozenman has received funding from the UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute, UCLA Friends of Semel Research Scholar Program, and the International OCD Foundation. Dr. Sugar has received research support from the National Institutes of Health through multiple divisions including the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the Health Resources & Services Administration; the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; and the John Templeton Foundation. She has served on technical expert panels for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Data Safety and Monitoring Boards for both academic institutions and Kaiser Permanente. Dr. McCracken has served as a consultant to Think Now and Alcobra. He has received a research contract with Psyadon, and his spouse has received a grant from the Merck Foundation. Dr. Piacentini has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Petit Family Foundation, the Tourette Association of America, the TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors, and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. He is a co-author of the Child OCD Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R), the Child Anxiety Impact Scale-Revised (CAIS-R), the Parent Tic Questionnaire (PTQ), and the Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS) assessment tools, all of which are in the public domain therefore no royalties are received. He has served as a consultant for an NIMH R01 grant at the University of Michigan. He has received honoraria and travel support for lectures at academic institutions and from the Tourette Association of America and the International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation for behavior therapy trainings. He has received royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online

This article was reviewed under and accepted by Ad Hoc Editor Guido K.W. Frank, MD.

Contributor Information

Drs. Tara S. Peris, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles.

Michelle S. Rozenman, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles.

Dr. Catherine A. Sugar, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles; Fielding School of Public Health, UCLA, Los Angeles.

James T. McCracken, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles.

John Piacentini, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles.

References

- 1.Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jaffer M. Functional impairment in childhood ocd: Development and psychometrics properties of the child obsessive-compulsive impact scale-revised (COIS-R) J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(4):645–53. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart SE, Hu Y, Leung A, et al. A multisite study of family functioning impairment in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(3):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, et al. Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment study for young children (POTS Jr)–a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):689–698. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geller DA, Marsch JS, Walter HJ, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric ocd treatment study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS, et al. Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the pediatric obsessive compulsive treatment study (POTS I) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginsburg GS, Kingery JN, Drake KL, Grasdos MA. Predictors of treatment response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):868–878. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storch EA, Larson MJ, Muroff J, et al. Predictors of functional impairment in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(2):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storch EA, Abramowitz JS, Keeley M. Correlates and mediators of functional disability in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(9):806–813. doi: 10.1002/da.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peris TS, Benazon N, Langley A, Roblek T, Piacentini JC. Parental attitudes, beliefs, and responses to childhood obsessive compulsive disorder: The parental attitudes and behaviors scale. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2008;30:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peris TS, Sugar CA, Bergman RL, Chang S, Langley A, Piacentini J. Family factors predict treatment outcome for pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:255–263. doi: 10.1037/a0027084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Keller M, McCracken JT. Functional impairment in children and adolescent with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(1):861–869. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ, et al. Family accommodation in pediatric obsessibe-compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(2):207–216. doi: 10.1080/15374410701277929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu MS, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Phenomenological considerations of family accommodation: Related clinical characteristics and family factors in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2014;3:228–235. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caporino NE, Morgan J, Beckstead J, Phares V, Murphy TK, Storch EA. A structural equation analysis of family accommodation in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebowitz ER, Scharfstein LA, Jones J. Comparing family accommodation in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and nonanxious children. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:1018–1025. doi: 10.1002/da.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlo LJ, Lehmkuhl HD, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Decreased family accommodation associated with improved therapy outcome in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(2):355–360. doi: 10.1037/a0012652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Chang S, et al. Controlled comparison of family cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation/relaxation training for child ocd. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(11):1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson-Hollands J, Abramovitch A, Tompson MC, Barlow DH. A randomized clinical trial of a brief family intervention to reduce accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A preliminary study. Behav Ther. 2015;46(2):218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peris TS, Bergman RL, Langley A, Chang S, McCracken JT, Piacentini J. Correlates of family accommodation of childhood obsessive compulsive disorder: Parent, child, and family characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1173–1181. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825a91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renshaw KD, Steketee G, Chambless DL. Involving family members in the treatment of ocd. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;34(3):164–175. doi: 10.1080/16506070510043732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steketee GS. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peris TS, Piacentini J. Helping families manage childhood OCD: Decreasing conflict and increasing positive interaction: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peris TS, Piacentini J. Optimizing treatment for complex cases of childhood obsessive compulsive disorder: A preliminary trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.673162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storch EA, Lewin AB, De Nadai AS, Murphy TK. Defining treatment response and remission in obsessive compulsive disorder: A signal detection analysis of the children’s yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(7):708–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewin AB, Wu MS, McGuire JF, Storch EA. Cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):415–445. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggan-Hardin MT, et al. Children’s yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: Reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piacentini J, Langley A, Roblek T. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of childhood OCD: It’s only a false alarm: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torp NC, Dahl K, Skarphedinsson G, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive behavior treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Acute outcomes from the Nordic long-term ocd treatment study (NordLOTS) Behav Res Ther. 2015;64:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman W, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Parent Version. San Antonio, TX: Graywing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman W, Saavedra L, Pina A. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the children’s yale-brown obsessive-compulsive scale. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jeffer M. Functional impairment in childhood ocd: Development and psychometrics properties of the child obsessive-compulsive impact scale-revised (COIS-R) J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(4):545–553. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calvocoressi L, Mazure C, Kasl S, et al. Family accommodation of obsessive compulsive symptoms: Instrument development and assessment of family behavior. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:636–642. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moos RH, Moos BS. Family environment scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guy W. Clinical global impressions ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute for Mental Health; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodden DHM, Bogels SM, Muris P. The diagnostic utility of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders-71 (SCARED-71) Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogels SM, Melick M. The relationship between child-report, parent self-report, and partner report of perceived parental rearing behaviors and anxiety in children and parents. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;37(8):1583–1596. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dadds MR, Barrett PM, Rapee RM, Ryan S. Family process and child anxiety and aggression: an observational analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24(6):715–734. doi: 10.1007/BF01664736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galambos NL, Barker ET, Almeida DM. Parents do matter: Trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2003;74(2):578–594. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.