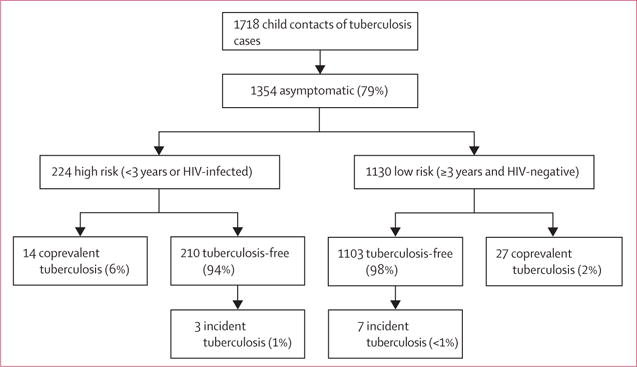

Figure 5. Tuberculosis-related outcomes* in children screened following a modified WHO decision-tree† classifying asymptomatic child contacts into high-risk and low-risk groups‡.

*Individuals with coprevalent disease were excluded from analyses of incident disease. In this figure, tuberculosis-free indicates contacts free of tuberculosis, but these contacts might have had tuberculosis infection. Percentages might not total 100% because within-characteristic percentages were rounded to the nearest integer. †This algorithm was first proposed by Marais and colleagues.4 ‡Children with tuberculosis-related symptoms are shown in figure 2 and included children with either chronic cough, fever, night sweats, haemoptysis, weight loss, or loss of appetite. Chronic cough was defined as a continuous, non-remitting cough present for >3 weeks. Fever was defined as body temperature of >38°C for 14 days, after exclusion of common causes such as malaria or pneumonia. Weight loss was defined as reporting of weight loss or failure to thrive with confirmatory evidence from the child’s growth chart. Haemoptysis was defined as the expectoration of blood from the lung airways or parenchyma. Night sweats and loss of appetite were self-reported by children and parents. Asymptomatic contacts included children with cough of <3 weeks’ duration or fever of <2 weeks’ duration, or both. The modified decision-tree, which proposes to group asymptomatic contacts into high-risk and low-risk groups, symptomatic contacts were at highest-risk for disease (23% and 5% coprevalent and incident disease; p<0.05 vs both other groupings). High-risk asymptomatic contacts had higher rates of coprevalent disease compared with low-risk asymptomatic contacts (6% versus 2%, p<0.01) and similar rates of incident disease (1% vs <1%, p=0.23). If both symptomatic and high-risk asymptomatic contacts were screened and followed up, 79% and 71% of all coprevalent and incident cases, respectively, would be assessed.