Abstract

Key points

Cav3.1 T‐type Ca2+ channel current (ICa‐T) contributes to heart rate genesis but is not known to contribute to heart rate regulation by the sympathetic/β‐adrenergic system (SAS).

We show that the loss of Cav3.1 makes the beating rates of the heart in vivo and perfused hearts ex vivo, as well as sinoatrial node cells, less sensitive to β‐adrenergic stimulation; it also renders less conduction acceleration through the atrioventricular node by β‐adrenergic stimulation. Increasing Cav3.1 in cardiomyocytes has the opposite effects.

ICa‐T in sinoatrial nodal cells can be upregulated by β‐adrenergic stimulation.

The results of the present study add a new contribution to heart rate regulation by the SAS system and provide potential new mechanisms for the dysregulation of heart rate and conduction by the SAS in the heart.

T‐type Ca2+ channel can be a target for heart disease treatments that aim to slow down the heart rate

Abstract

Cav3.1 (α1G) T‐type Ca2+ channel (TTCC) is expressed in mouse sinoatrial node cells (SANCs) and atrioventricular (AV) nodal cells and contributes to heart rate (HR) genesis and AV conduction. However, its role in HR regulation and AV conduction acceleration by the β‐adrenergic system (SAS) is unclear. In the present study, L‐ (I Ca‐L) and T‐type (I Ca‐T) Ca2+ currents were recorded in SANCs from Cav3.1 transgenic (TG) and knockout (KO), and control mice. ICa‐T was absent in KO SANCs but enhanced in TG SANCs. In anaesthetized animals, different doses of isoproterenol (ISO) were infused via the jugular vein and the HR was recorded. The EC50 of the HR response to ISO was lower in TG mice but higher in KO mice, and the maximal percentage of HR increase by ISO was greater in TG mice but less in KO mice. In Langendorff‐perfused hearts, ISO increased HR and shortened PR intervals to a greater extent in TG but to a less extent in KO hearts. KO SANCs had significantly slower spontaneous beating rates than control SANCs before and after ISO; TG SANCs had similar basal beating rates as control SANCs probably as a result of decreased I Ca‐L but a greater response to ISO than control SANCs. I Ca‐T in SANCs was significantly increased by ISO. I Ca‐T upregulation by β‐adrenergic stimulation contributes to HR and conduction regulation by the SAS. TTCC can be a target for slowing the HR.

Keywords: Cav3.1/α1G T‐type calcium channel, heart rate, β‐adrenergic, sinoatrial node cells, atrioventricular node

Key points

Cav3.1 T‐type Ca2+ channel current (ICa‐T) contributes to heart rate genesis but is not known to contribute to heart rate regulation by the sympathetic/β‐adrenergic system (SAS).

We show that the loss of Cav3.1 makes the beating rates of the heart in vivo and perfused hearts ex vivo, as well as sinoatrial node cells, less sensitive to β‐adrenergic stimulation; it also renders less conduction acceleration through the atrioventricular node by β‐adrenergic stimulation. Increasing Cav3.1 in cardiomyocytes has the opposite effects.

ICa‐T in sinoatrial nodal cells can be upregulated by β‐adrenergic stimulation.

The results of the present study add a new contribution to heart rate regulation by the SAS system and provide potential new mechanisms for the dysregulation of heart rate and conduction by the SAS in the heart.

T‐type Ca2+ channel can be a target for heart disease treatments that aim to slow down the heart rate

Introduction

Cardiac rhythm (heart rate, HR) generation and regulation are important for the function of the heart. HR is dictated by the automaticity of sinaoatrial node (SAN) cells, which is controlled via a complex interplay of membrane ion channels, transporters and intracellular Ca2+ (Nargeot & Mangoni, 2006; Jaleel et al. 2008; Shinohara et al. 2010; Lau et al. 2011). To adapt to the needs of the body, the HR of animals and human beings is constantly regulated (Lau et al. 2011). HR regulation occurs by a change in the automaticity of the SAN cells and the conduction rate, especially via the atrioventricular node (AVN) in response to changes in autonomic nerve activity (Lakatta et al. 2010). The increases in sympathetic outflow to the SAN and AVN with concurrent inhibition of vagal tone lead to an increase in HR. The excitation of the sympathetic/β‐adrenergic system (SAS) releases catecholamines that bind to β‐adrenergic receptors and activate cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signalling (Alig et al. 2009). The major type of β‐adrenergic receptors mediating the regulation of SAN automaticity are the β1‐ and β2‐adrenergic receptors (Rohrer et al. 1999). cAMP increases depolarizing funny current (I f) directly and indirectly by PKA (‘membrane clock’) to augment the HR (Lakatta et al. 2010). It has been proposed that the enhancement of sinoatrial node cell (SANC) intracellular calcium cycling by rhythmic activation of PKA (‘calcium clock’) also contributes to SAS‐mediated upregulation of HR (Vinogradova & Lakatta, 2009). Both mechanisms contribute to an increased slope of diastolic depolarization (phase 4 depolarization) so that the pacemaker potential reaches the threshold for firing more rapidly. On the other hand, parasympathetic activation releases acetylcholine (Ach) onto the SAN to activate Gi, which decreases intracellular cAMP and activates hyperpolarizing KAch channels, decreasing the membrane potential and the slope of diastolic depolarization of SANCs, leading to a slower HR (Nishi et al. 1976; Kaspar & Pelzer, 1995; Kondratyev et al. 2007). Abnormal SAN automaticity and its regulation contribute to sinus node disease, a type of arrhythmia often requiring pacemaker implantation (Lau et al. 2011), whereas modulating SAN automaticity is an effective way of treating heart failure (Borer et al. 2016).

Other depolarizing currents such as T‐type Ca2+ currents (I Ca‐T) also contribute to the ‘diastolic depolarization’ essential for SAN pacemaking (Mesirca et al. 2015). T‐type Ca2+ channels (TTCCs) are a family of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels with ‘tiny’ single‐channel conductance and fast decay rates (‘transient’) (Perez‐Reyes, 2003; Nilius et al. 2006). These channels are activated at low membrane potential thresholds (−70Mv to ∼−60 mV) (Perez‐Reyes, 2003; Nilius et al. 2006), enabling them to participate in diastolic depolarization of pacemakers. There are three subtypes of TTCCs encoded by three genes: α1 subunits, α 1G (Cav3.1), α1H (Cav3.2) or α1I (Cav3.3) (Perez‐Reyes, 2003; Nilius et al. 2006). In mammalian hearts, Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 are expressed in the whole heart during the embryonic stage, although their expression in ventricles decreases rapidly after birth (Cribbs, 2010). Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 expression remains in the SAN and AVN cells of the adult heart, indicating a role of Cav3 channels in automaticity (Mangoni & Nargeot, 2001; Efimov et al. 2004; Ono & Iijima, 2010). I Ca‐T has been recorded in adult SANCs from multiple species (Hagiwara et al. 1988; Zhang et al. 2003; Mangoni et al. 2006). Cav3.1 deficiency in mice slows AV conduction and the intrinsic HR recorded with blockers for both parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, and also prolongs the SAN recovery time (Mangoni et al. 2006). By contrast, mice with α1H deletion have normal sinoatrial rhythm (Chen et al. 2003), in accordance with our previous findings showing that Cav3.1 mRNA but not Cav3.2 mRNA is abundant in mouse SAN cells and that Cav3.2 knockout (KO) mouse SAN cells had intact I Ca‐T (Li et al. 2012). Cav3.1 mRNA is abundantly expressed in human SA node (Chandler et al. 2009). Therefore, TTCCs may contribute to pacemaking in SANCs (Irisawa & Hagiwara, 1988; Huser et al. 2000).

We previously reported that Cav3.1 T‐type calcium current (I Ca‐T) in mouse ventricular myocytes can be upregulated by β‐adrenergic stimulation via a PKA‐dependent mechanism (Li et al. 2012). However, the roles of this upregulation of TTCC activity in HR regulation by the SAS have not been investigated. In the present study, we hypothesize that Cav3.1 plays an important role in SAS‐mediated HR regulation. To test our hypothesis, mice with inducible and cardiomyocyte‐specific overexpression (gain of function, transgenic, TG) or with the KO (i.e. loss of function) of Cav3.1 were used. The findings of the present study suggest that the Cav3.1 T‐ type Ca2+ channel is an important player in HR regulation by the SAS.

Methods

Ethical approval

The present study conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85‐23, revised 1996) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at Temple University. The experimental procedures were also conformed to the principles and regulations as described by Grundy (Grundy, 2015).

Mouse models

A TG mouse model with cardiac‐specific [i.e. driven by α‐myosin heavy chain (α‐MHC) promoter] and inducible (tet‐off, controlled by doxycycline) overexpression of mouse Cav3.1 (Genebank: NM_009783) was established with the bi‐transgenic system initially in the FVB genetic background (Sanbe et al. 2003; Li et al. 2012) and then transferred to the c57bl/6 background by breeding with c57bl/6 wild‐type mice for six generations. Mice were bred and genotyped as described previously (Li et al. 2012). Doxycycline‐containing chow was removed after weaning to allow Cav3.1 transgene to be expressed. Cav3.1 KO mice in c57bl/6 genetic background were obtained from the Nakayama et al. (2009). C57bl/6 wild‐type mice were used as the control. Both sexes of animals in equal amount were used at the age of 4 months in the present study. α‐MHC promoter‐driven green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic (non‐inducible) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).

ECG and intra‐left ventricular pressure recording before and after isoproterenol (ISO) infusion via jugular vein in anaesthetized mice

Mice were anaesthetized with sodium phenobarbital [50 mg kg−1 body weight (BW), i.p.]. Rectal temperature was continuously monitored and maintained at 37°C using a heating pad. Standard three lead ECGs were recorded using three tungsten‐coated needle electrodes inserted s.c. into the appropriate forelimbs and hindlimbs with a Powerlab system (ADI, Denver, CO, USA). Intra‐left ventricular pressure was recorded with a 1.4 Fr Millar pressure catheter that went into the left ventricle through the right carotid artery (Tang et al. 2010). Intra‐left ventricular pressure and ECGs were recorded before (baseline) and after the application of a β‐AR agonist, ISO. Different doses of ISO (10−16 g∼10−6g g−1 BW) were applied through a jugular vein catheter as described previously (Li et al. 2014).

Because ISO stimulates all three types of β‐adrenergic receptors, we aimed to determine which type of β‐adrenergic receptor is involved in regulating Cav3.1 TTCC and the related HR change. Because the literature suggests that β1‐ and β2‐adrenergic receptors are the major types of adrenergic receptors in HR regulation (Rohrer et al. 1999; Barbuti & DiFrancesco, 2008), we focused the present study on a β1‐AR antagonist, metoprolol and a β2‐AR antagonist, ICI 118,551. After anaesthetizing the mice with sodium phenobarbital (50 mg kg−1 BW, i.p.), the animal was taped on a heating pad and attached to three ECG leads as described above. Surface ECG was recorded for 4 min per segment at baseline and after the application of three doses of ISO (10−10 , 10−9 and 10−8 g g−1 BW, i.p.) with the Powerlab and LabChart system (ADI). Next, the animals were allowed to recover for 1 week and the surface ECG was recorded after pretreatment with ICI 118,551 (2 × 10−3 g g−1 BW) for 5 min and after three serial doses of ISO. After an additional 1 week, the animals were pretreated with ICI 118,551 plus metoprolol (2 × 10−3 g g−1 BW) and then ECGs were recorded at baseline or after ISO application.

Intra‐right atrial pacing and recording of cardiac electrical activity

Mice were anaesthetized with sodium phenobarbital (50 mg kg−1 BW, i.p.) and placed on a heating pad in the supine position. Rectal temperature was continuously monitored and maintained at 37°C. Standard three lead ECGs were recorded with the Powerlab system (ADI). At the same time, an eight‐lead pacing/recording catheter (EPR 800; Millar, Houston, TX, USA) was inserted into the right jugular vein and carefully advanced into the right atrial so that a strong atrial electrogram and a weaker ventricular electrogram could be recorded simultaneously. Once the pacing catheter was at the right position, it was tied with the jugular vein to fix the position. Then, programmed stimulation of the atria was applied with programmed pacing protocol generated by LabChart (ADI). The stimulation frequency was set 600 Hz and the optimal pacing amplitude was determined for each mouse to ensure each pacing was followed by the activation of the ventricles (i.e. followed by QRS waves in the surface ECG).

ECG recording from Langendorff‐perfused isolated hearts

Animals were killed with sodium pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1 BW, i.p.) and hearts were excised. Hearts were then hung onto a cannula connected to a Langendorff apparatus (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA, USA) and perfused at a constant pressure of 80 mmHg with modified Krebs–Henseleit buffer (KHB) (Li et al. 2014). The temperature of the heart was maintained at 37°C by perfusion with pre‐heated KHB and immersed in a water‐heated glassware reservoir containing KHB. Leads for ECG recording were gently placed on the surface of the heart. The lead position was carefully adjusted to record clear ECG signals with all major waves (P, QRS and T waves). After a 20 min equilibration period, hearts were perfused with a saturate dose of ISO (10−7 m) for 15 min (Li et al. 2014). ECG was recorded continuously by a data acquisition system (Powerlab/8SP; ADI) (MacDonnell et al. 2008).

Heart weight and atrial weight measurements

Some animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1 BW, i.p.) and heparinized i.v. after the ECG or pacing procedure was performed. Then, the heart was excised. The atria and the ventricles were separated under a dissecting microscope and weighed. The weights of the heart and the atria were normalized to body weight.

SAN cell isolation

SANCs were isolated as described previously (Mangoni & Nargeot, 2001; Gao et al. 2011). Animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1 BW, i.p.) and heparinized i.v. Hearts were excised and the SAN tissue was cut out as described previously (Nilius et al. 2006; Huser et al. 2000). SANCs were isolated using a technique described by Mangoni & Nargeot (2001). For this, the heart was excised and placed into Tyrode's solution (35°C) containing (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5.0 Hepes, 5.5 Glucose, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2 and 1.0 MgCl2 (pH 7.4). The SAN tissue was dissected out with a dissecting scope according to the landmarks of the heart defined by the orifice of superior vena cava, crista terminalis and atrial septum (Mangoni & Nargeot, 2001). The SAN tissue was cut into small pieces and transferred to a 10 mL test tube. Then, the tissue was rinsed with a ‘low Ca2+’ digestion solution containing (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5.0 Hepes, 5.5 Glucose, 5.4 KCl, 0.2 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.2 KH2PO4, 50 Taurine and 1 mg mL−1 BSA (pH 6.9). SAN tissue pieces were digested in 5 mL ‘low Ca2+’ solution containing collagenase type I (225 U mL−1; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA), elastase (1.8 U mL−1; Worthington) and protease type XIV (0.8 U mL−1; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at 37°C. After digestion, the tissue was washed with 10 mL of Kraft‐Bruhe medium containing (in mm): 100 potassium glutamate, 5 Hepes, 20 glucose, 25 KCl, 10 potassium aspartate, 2 MgSO4, 10 KH2PO4, 20 taurine, 5 creatine, 0.5 EGTA and 1 mg mL−1 BSA (pH 7.2) three times and then SANCs were dissociated with a transfer pipette by mechanically stirring and pipetting the tissue chunks. Dissociated SANCs were placed at room temperature for study within 5 h.

Recording of pacemaker activity in SAN cells

The pacemaker activity of SAN cells was recorded at 35 ± 1°C in a heated chamber mounted on a Diaphot microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The extracellular Tyrode's solution contained (in mm): 140.0 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 5.0 Hepes, and 5.5 glucose (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). SAN cell pacemaker activity was evaluated by counting the number of beats of SANCs in segments of 1 min in duration under basal conditions and after application of ISO.

Cellular electrophysiology

Cellular electrophysiology was performed with an Axon Axopatch 2B amplifier and pClamp 9 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Isolated SAN cells were placed in a chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Diaphot; Nikon). SAN cells were initially perfused with a normal physiological salt solution containing (in mmol L–1): NaCl 150, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1.2, glucose 10, sodium pyruvate 2 and Hepes 5 (pH 7.4) at 37°C. Low resistance (2–4 MΩ) pipettes were filled with a solution containing (in mmol L–1): Cs‐aspartate 130, NMDG 10, TEA‐Cl 20, Tris‐ATP 2.5, Tris‐GTP 0.05, MgCl2 1, EGTA 10 and β‐escin 0.04 (pH 7.2). β‐escin was used to establish a perforated‐patched whole‐cell voltage clamp. This approach was effective with respect to reducing calcium current run‐down. After a giga‐Ohm seal was obtained and the SAN cell was perfused with a normal physiological salt solution for 15 min. Access resistance was monitored by a −10 mV hyperpolarizing pulse with the membrane test function in Clampex, version 9 (Molecular Devices). A period of 5 min was allowed to dialyse the cell after achieving sufficient access to the cytosol, and then the bath solution was switched to a Na+ and K+ free bath solution containing (in mmol L−1): NMDG 150, CaCl2 2, CsCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.2, glucose 10, Hepes 5 and 4‐AP 2 (pH 7.4). Total I Ca (from a holding potential of −90 mV to test pulses from −70 mV to 50 mV in a 10 mV increment, 400 ms) and I Ca‐L (from a holding potential of −50 mV to test pulses in a 10 mV increment, −70 mV∼50 mV, 400 ms) were measured before and after the application of ISO. I Ca‐T was obtained by subtracting I Ca‐L from total I Ca as described previously (Li et al. 2012). To study the ISO effect on I Ca‐T in SANCs and to avoid run‐down of I Ca‐T (Li et al. 2012), nifedipine (10 μm) was used to block residual I Ca‐L when depolarizing the cell from V h = −90 mV to −40 mV.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± SEM. When appropriate, a paired or unpaired t test and one‐way or two‐way ANOVA with or without repeated measures was used to detect significance with Prism, version 6.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Bonferroni adjustment was performed for post hoc pairwise comparison. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Dose‐response curves were constructed with Prism, version 6.0.

Results

T‐type calcium current in mouse SAN cells is mediated by Cav3.1

To determine the identity of I Ca‐T in mouse SANCs, I Ca‐T was measured in Cav3.1 KO and wild‐type control SANCs. I–V curves of total Ca2+ current (total I Ca), I Ca‐L and I Ca‐T were constructed as shown in Fig. 1. I Ca‐T and I Ca‐L were clearly present in wild‐type control SANCs but I Ca‐T was missing in Cav3.1 KO myocytes (Fig. 1). These data suggest that I Ca‐T in mouse SANCs is mediated by Cav3.1.

Figure 1. Total, L‐ and T‐ type Ca2+ currents in SAN cells of control (WT), Cav3.1 KO and Cav3.1 TG mice.

A and B, α‐MHC promoter‐driven expression of GFP in SANCs. A SANC from α‐MHC‐driven GFP transgenic mice in bright field (A) and GFP fluorescence (B). L‐ and T‐type Ca2+ currents were separated by holding the cells at −90 and −50 mV. At the V h of −50 mV, TTCC was fully inactivated and only I Ca‐L remained. The T‐type Ca2+ current was obtained by subtracting the raw L‐type Ca2+ current from the raw total Ca2+ current. Examples of recordings of total I Ca (V h = −90 mV), I Ca‐L (V h = −50 mV) and I Ca‐T (difference between total I Ca and I Ca‐L) in one WT (C), one Cav3.1 KO (D) and one Cav3.1 TG (E) SAN cell are shown. The insert in (A) was the voltage clamp protocol. I–V curves of total (F), L‐type (I Ca‐L) (G) and T‐type Ca2+ (I Ca‐T) (H) currents in SANCs of control (WT), Cav3.1 KO and Cav3.1 TG mice. I–V curves were constructed by examining the peak of total, L‐type and derived T‐type Ca2+ currents at different test potentials. All currents were normalized to the cell capacitance. @ P < 0.05, TG versus control; # P < 0.05, KO versus control; $P < 0.05, TG versus KO at the same voltage determined by two‐way repeated ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment.

α‐MHC promoter‐driven overexpression of Cav3.1 increases I Ca‐T but decreases I Ca‐L in mouse SAN cells

To test whether α‐MHC promoter–driven expression transgene was expressed in mouse SANCs, SANCs were isolated from transgenic mice carrying α‐MHC promoter‐driven GFP. GFP green fluoresence was clearly detected in the SANCs as shown in Fig. 1 A and B, indicating that α‐MHC promoter‐driven transgene is expressed in SANCs.

Electrophysiological recording of Ca2+ currents in SANCs from Cav3.1 TG mice showed that total I Ca and I Ca‐T were significantly increased in TG SANCs compared to those in WT SANCs (Fig. 1 C–H). Interestingly, a decrease of I Ca‐L was found in TG SANCs (Fig. 1 E and G), suggesting a compensatory decrease of I Ca‐L in TG SANCs associated with increased I Ca‐T.

ISO increased HR more in TG but less in KO than in control mice in vivo under anaesthesia

Under conscious conditions, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems constantly regulate HRs, which disguises the differences in HR in control and Cav3.1 KO mice (Mangoni et al. 2006). Thus, we determined HR responses to ISO in anaesthetized Cav3.1 TG, Cav3.1 KO and control mice. ECGs were recorded from mice after the infusion of different concentrations of ISO via a jugular vein catheter. Although the basal HRs were similar between Cav3.1 TG, KO and control mice. ISO at low doses (10−14 to ∼10−12 g g−1 BW) was able to significantly increase HRs in control mice and even more in TG mice but not in KO mice (Fig. 2 A and C). ISO at doses of 10−11 g g−1 BW and higher significantly increased HR in all three groups of animals, with the greatest increases in the TG mice and the lowest increases in the KO mice. The logEC50 of ISO for increasing HRs in TG, control and KO mice –10.43 ± 0.16, –9.99 ± 0.12 and –9.45 ± 0.19 g g−1 BW, respectively (Fig. 2 C). Maximal HRs after saturate ISO stimulation were highest in TG mice and lowest in the KO mice (Fig. 2). However, it appeared that the differences in maximum HR after different doses of ISO were not a result of the differences in baroreflex responses to blood pressure alterations after ISO because the systolic pressure was not different among groups at all doses of ISO (Fig. 2 D). In effect, ISO did not significantly decrease systolic blood pressure at the doses of 10−16 g g−1 BW to 10−8 g g−1 BW (Fig. 2 D), probably because the increase of cardiac output compensated for the effect of vascular relaxation effect of ISO. ISO slightly decreased systolic pressure at the doses of 10−7 and 10−6 g g−1 BW, which was no different between control, KO and TG groups of animals. These data suggest that the loss of Cav3.1 reduces, whereas overexpression of Cav3.1 sensitizes, the response of the HR to β‐adrenergic stimulation.

Figure 2.

Mice were anaesthetized and a catheter was inserted into the left jugular vein to infuse a series of ISO from 10−16 g g−1 BW to 10−6 g g−1 BW. A, examples of HR changes in response to different doses of ISO in anaesthetized Cav3.1 KO (blue) and TG (red) and control (black) mice. B, examples of ECG recorded at baseline and at maximal HR after ISO. C, average HR at different concentrations of ISO in Cav3.1 KO, TG, and control mice. HR–ISO dose relationship were fit with a dose–response curve to derive EC50. The inserted table shows the logEC50 and maximal percentage of HR increase in TG, KO and control mice. @ P < 0.05, @@ P < 0.01 and @@@ P < 0.001 TG versus control; # P < 0.05, KO versus control; $ P < 0.05, $$$ P < 0.001 and $$$$ P < 0.0001, TG versus KO at the same ISO dose determined by two‐way repeated ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment. D, left ventricular systolic pressure at different doses of ISO. E–G, maximum HRs at different i.p. doses of ISO (10−10, 10−9 and 10−8 g g−1 BW) without or with ICI 118,551 (2 μg g−1 BW, i.p., 5 min) or with ICI 118,551 + metoprolol (2 μg g−1 BW, i.p., 5 min) in sedated control, KO and TG animals. % P < 0.05, without pretreatment versus with ICI pretreatment; # P < 0.05, without treatment versus with ICI + metoprolol pretreatment; $ P < 0.05, pretreatment with ICI versus pretreatment with ICI + metoprolol. At the same ISO dose, significance was determined by two‐way repeated ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

ISO dose–HR responses in sedated Cav3.1 KO, Cav3.1 TG and control mice.

We further determined which β‐adrenergic receptor(s) was involved in this Cav3.1 mediated enhancement of HR responses to ISO. As shown in Fig. 3 E–G, pretreatment of animals with ICI 118,551, a specific β2‐adrenergic receptor blocker, significantly reduced HR responses to ISO stimulation at low doses (10−10 and 10−9 g g−1 BW) in control and TG animals but not in KO animals; at the high ISO dose of 10−8 g g−1 BW, HR increases were not changed by ICI 118,551 pretreatment. When the animals were pretreated with both ICI 118,551 and metoprolol, ISO did not significantly increase the HR at all ISO doses tested, which is in agreement with the addition of metoprolol to animals pretreated with ICI 118,551 and stimulated with 10−7g g−1 BW ISO being seen to return the HR to baseline (Fig. 3 E and F, blue line, last data point). These results suggest that, at low doses of ISO, the enhancement of chronotropic effect by Cav3.1 TTCC is preferentially mediated by β2‐AR.

Figure 3.

A, examples of ECG recorded at baseline and at maximal HR after ISO in isolated and perfused Cav3.1 KO (blue) and TG (red) and control (black) mice. B, HR before and after the application of 10−7 m ISO. C, the percent increase of HR by ISO in Cav3.1 KO and TG, and control mice. D, PR intervals of Langendorff‐perfused control (black), Cav3.1 KO (blue) and TG (red) hearts before and after the application of ISO. E, the percentage of PR interval decrease (100 – PR interval after ISO/baseline PR interval × 100) induced by ISO in c57bl/6 control and Cav3.1 KO mice. F, examples of surface ECG and atrial electrogram before and during atrial pacing at 600 Hz. G, PR intervals during atrial pacing‐induced ventricular beats. H, heart weight or atrial weight to body weight ratios of control, KO and TG animals. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001. Data in (B) and (D) were analysed by two‐way repeated ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment; data in (C) and (E) were analysed by one‐way ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment. n, number of animals studied. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

HR and PR intervals of Langendorff perfused hearts from Cav3.1 KO, TG and control WT mice before and after ISO (10−7 m).

ISO increased the HR of Langendorff‐perfused more in Cav3.1 TG hearts but less in Cav3.1 KO hearts than control hearts ex vivo

To completely eliminate the effects of in vivo regulatory mechanisms on HRs, perfused HRs on Langendorff apparatus were used to examine intrinsic HRs at baseline and after ISO (10−7 m, a saturated dose) stimulation ex vivo. At baseline, the HR of Cav3.1 KO hearts (396.9 ± 22.2.5 bpm, n = 17) was non‐significantly slower than that of c57bl/6 control hearts (421.7 ± 12.4 bpm, n = 12) and TG (429.0 ± 15.4 bmp, n = 10) hearts. After the application of a saturate dose of ISO (10−7 m), the HR of Cav3.1 KO hearts (562.8 ± 23.7 bpm, n = 17) was significantly lower than that of control hearts (655.2 ± 17.0 bpm, n = 12, P < 0.05) and TG hearts (723.6 ± 18.4 bpm, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3 A and B). The percentage of increase in HR was significantly less in the KO mice (28.1 ± 3.4 %, n = 12) than in the control mice (45.8 ± 3.2%, n = 9, P < 0.05) and TG mice (73.8 ± 8.1%) (Fig. 3 C). These data were consistent with the results obtained from in vivo hearts.

Because TTCC is also expressed in AV node and plays an important role in impulse conduction, we analysed PR intervals of Cav3.1 TG and KO and control hearts before and after the application of ISO. We found that the loss of Cav3.1 prolonged the PR interval in KO hearts (control versus KO: 32.1 ± 0.3 ms, n = 12 versus 34.9 ± 0.4 ms, n = 17, P < 0.05), whereas Cav3.1 overexpression (28.4 ± 0.6 ms, n = 10) shortens the PR interval (Fig. 3 D). ISO shortened PR intervals in all Langendorff perfused hearts but to a greater extent in TG hearts and to a less extent in KO hearts compared to control hearts (Fig. 3 E). To rule out the possibility that the prolonged PR interval was a result of changes in the conduction of the atria, we paced the atria via an intra‐RA catheter and measured the time from the end of the pacing until the start of the QRS complex in the surface ECG in vivo. In agreement with the results of the study by Langendorff perfused heart study (Figure 2), the time from the end of atria pacing till the start of the QRS was prolonged in the KO animals but shortened in the TG animals compared to the control (Fig. 3 F and G), implicating changes of intrinsic properties of the SA node and/or Purkinje fibres. The atria or the ventricles were not enlarged/hypertrophied in either Cav3.1 TG or KO animals (Fig. 3 H), as reported previously (Jaleel et al. 2008 ; Nakayama et al. 2009). These data suggest that Cav3.1 plays important roles in regulating both SAN and AVN at baseline and after β‐adrenergic stimulation.

Cav3.1 expression affects sinoatrial nodal cell automaticity and its regulation by β‐adrenergic stimulation

We next examined the beating rates of SANCs from Cav3.1 KO, TG and control mice. Basal beating rates of Cav3.1 KO SANCs were significantly slower than these of TG and control SANCs. However, basal beating rates of TG SANCs were no different from those of control SANCs (Fig. 4 A).

Figure 4. ISO dose–response relationships of spontaneous beating rates of SAN cells of Cav3.1 TG, KO and control mice.

A, spontaneous beating rates of control, Cav3.1 KO and TG SANs before and after the application ISO (10−9 to ∼10−7 m). B, percentage of increases of SAN beating rates by 10−7 m ISO in control, Cav3.1 KO and TG SANCs. ‘n’ is the number of cells from three animals from each group. A: @ P < 0.05 and @@ P < 0.01, TG versus control; # P < 0.05 and ## P < 0.01, KO versus control; $ P < 0.05, $$$ P < 0.001 and $$$$ P < 0.0001, TG versus KO at the same ISO dose determined by two‐way repeated ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment. B: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001, analysed by one‐way ANOVA and post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To determine the effects of different doses of ISO on the beating rate of SANCs, three concentrations of ISO (10−9, 10−8 and10−7 m) were applied to SANCs. There were dose‐dependent increases of beating rates of all groups of SANCs. ISO at the doses of 10−8 and 10−7 m increased spontaneous beating rate to a less extent in KO SANCs but to a greater extent in TG SANCs (Fig. 4 A). The percentage of the increase of HR by10−7 m ISO versus baseline was the greatest in TG SANCs (41.5 ± 2.5%), greater in control SANCs (31.14 ± 1.7%) and the least in KO SANCs (24.9 ± 1.8%, P < 0.05).

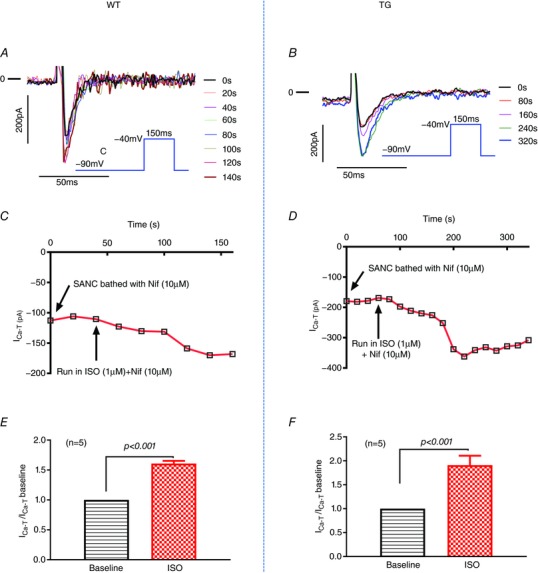

I Ca‐T in SANCs is increased by ISO

The data obtained in the present study suggest that Cav3.1 participates in HR regulation by β‐adrenergic stimulation. We then tested whether ICa‐T can be regulated directly by β‐adrenergic agonist in SANCs. The ISO effect on I Ca‐T was monitored by recording I Ca at −30 mV depolarized from −90 mV every 20 s. Figure 5 shows a significant upregulation of I Ca‐T mediated by Cav3.1 by ISO in both WT and TG SANCs.

Figure 5. I Ca‐T in SANCs from control and Cav3.1 TG mice is increased by ISO (1 μm).

A and B, I Ca‐T traces recorded in one control and one TG SANC bathed in nifedipine (10 μm) then nifedipine (10 μm) + ISO (1 μm). The recording was every 20 s but, for clarity, only I Ca‐T traces every 40 s (A) or 80 s (B) are shown. The insert is the voltage clamp protocol. C and D, the time course of ISO [nifedipine (10 μm) + ISO (1 μm)] effect on ICa‐T amplitude recorded at −30 mV depolarized from −90 mV in the presence of nifedipine (10 μm). E and F, the percentage of increases of I Ca‐T in WT and Cav3.1 TG SAN cells. A paired t test was used for statistics.

Discussion

Previously, we reported that β‐adrenergic stimulation could increase Cav3.1 TTCC activity in mouse ventricular myocytes overexpressing Cav3.1 via a PKA‐dependent mechanism (Li et al. 2012). The present study further explored whether this upregulation of TTCC activity by β‐adrenergic stimulation contributed to the HR increase and AV conduction acceleration by the SAS. We found that: (i) Cav3.1 mediates ICa‐T in SANCs because Cav3.1 KO eliminated ICa‐T but Cav3.1 overexpression augmented ICa‐T in SANCs; (ii) Cav3.1 KO reduced the sensitivity and extent of HR upregulation and AV conduction acceleration by β‐adrenergic stimulation in vivo and ex vivo, whereas Cav3.1 overexpression had the opposite effects; (iii) Cav3.1 KO reduced spontaneous beating rates and its response to ISO, whereas Cav3.1 TG had contrasting effects; and (iv) I Ca‐T in wild‐type and Cav3.1 TG SANCs was upregulated by ISO.

The role of Cav3.1 in basal HR generation

Our electrophysiological studies showed enhanced I Ca‐T in SANCs of Cav3.1 transgenic (driven by α‐MHC promoter) mice and an absence of I Ca‐T in SANCs of Cav3.1 KO mice (Fig. 1). Ex vivo KO hearts or in vitro KO SANCs showed slower beating rates than those of control hearts and SANCs, suggesting an important role of Cav3.1 in HR generation. By contrast, ex vivo Cav3.1 transgenic hearts and in vitro Cav3.1 TG SANCs did not have higher beating rates than control hearts and SANCs. This could be because the role of Cav3.1 in TG mice was masked by the compensatory changes of other channels and Ca2+ handling proteins in the TG SANCs. The results of the present study show that the L‐type Ca2+ current is reduced in the Cav3.1 TG SANCs (Fig. 1). Our previous study of Cav3.1 TG hearts showed changes of several Ca2+ handing proteins in the ventricles including decreased L‐type Ca2+ channel, increased SERCA2a and reduced phospholamban expression (Jaleel et al. 2008). Because L‐type Ca2+ current and spontaneous cyclic Ca2+ release are important for SANC automaticity, these changes could account for the observation that the basal HR in Cav3.1 TG mice is not increased. Therefore, these data from Cav3.1 TG mice do not undermine the suugestion that Cav3.1 plays a role in HR generation (Huc et al. 2009).

The role of Cav3.1 in HR regulation by β‐adrenergic stimulation

The focus of the present study was to examine the role of I Ca‐T stimulated by β‐adrenergic in HR regulation by the β‐adrenergic system. We showed that I Ca‐T in mouse SANCs can be increased by β‐adrenergic stimulation (Fig. 5). When the mice were anaesthetized, the sensitivity of the HR to ISO stimulation was TG > control > KO (Fig. 2). The beating rates of Cav3.1 KO hearts and SANCs were less sensitive to ISO, whereas these rates of Cav3.1 TG hearts and SANCs were more sensitive to ISO (Figs 3, 4, 5). Collectively, these data suggest the upregulation I Ca‐T in SANCs contributes to HR upregulation by β‐adrenergic stimulation. Our data further suggest that this is preferentially mediated by β2‐AR, especially at low level of β‐adrenergic stimulation. We suspect that the Cav3.1 TTCC could be located close to or preferentially coupled to β2‐AR signalosome.

In recent years, it has been proposed that β‐adrenergic regulation of HR is mediated not only by the direct effect of cAMP on funny channels, but also by cAMP/PKA effect on SANC Ca2+ handling (Lakatta et al. 2010; Lau et al. 2011). Therefore, it is possible that β‐adrenergic/PKA regulation of Cav3.1 participates in the positive chronotropic effects of β‐adrenergic agonists by enhancing both phase 4 diastolic depolarization current (‘membrane clock’) and SANC Ca2+ handling (‘calcium clock’). It appears that the compensatory decrease of ICa‐L in Cav3.1 TG SANCs does not impair the capability of increasing Cav3.1 by β‐adrenergic stimulation to increase HR. Thus, our data suggest that the expression level of ICa‐T is a direct modulator the sensitivity of the HR response to β‐adrenergic stimulation. Because Cav3.1 also mediates I Ca‐T in human SANCs (Chandler et al. 2009) and Cav3.1 is highly homologous between human and mouse (Monteil et al. 2000), this mechanism probably also participates in human HR regulation.

The role of Cav3.1 in conduction through the AVN

It is well known that sympathetic/β‐adrenergic stimulation on the heart increases the conduction rate of the AV node and thus shortens the PR interval. However, the exact mechanism of this acceleration by sympathetic/β‐adrenergic stimulation is still not entirely clear. Because HCN4 (mediating I f) is expressed in AVN myocytes, cAMP increase after sympathetic/β‐adrenergic stimulation may enhance I f and thus enhance AVN conduction (Mesirca et al. 2015). In addition, Kim et al. (2010) showed that ISO stimulation of rabbit AVN elicited a late diastolic Ca2+ elevation that could enhance diastolic depolarization via sodium/calcium exchange. Cav3.1 plays a role in AV nodal conduction (Mangoni et al. 2006), although its role in AVN conduction regulation by the SAS has not be reported. We found that Cav3.1 expression positively affects AVN conduction regulation by ISO (Fig. 3 D and E). As in the SAN cells, enhanced Cav3.1 activity by ISO could contribute to the AVN conduction acceleration probably by providing more late phase 4 depolarizing current directly (‘current clock’) and by enhancing late diastolic Ca2+ elevation (‘Ca2+ clock’). However, these mechanisms may need to be studied in large mammal preparations because the isolation of AVN cells from mice can be challenging. Alternatively, optical mapping of AVN can be used to determine whether the AVN conduction or the Purkinje fibre conduction is slowed, although our pacing study ruled out atrial change for the PR interval prolongation.

Significance and limitations

The findings of the present study add a new contribution to the regulation of HRs by the SAS system, which is critical for normal cardiac function. In addition, it is possible that altered regulation of the TTCC by the SAS could cause cardiac dysrhythmias such as tachycardia, bradycardia and AV conduction block. Furthermore, inhibiting TTCC upregulation by the SAS could be adopted as a way of slowing down the HR, such as in heart failure treatment.

We caution that murine cardiac physiology is different from that of human and other large mammals, especially in terms of the autonomic control of HR (Kaese & Verheule, 2012). The HR in mice is much faster than that in humans. Accordingly, the shape and duration of action potentials, the underlying ionic currents and Ca2+ handling in mice all support heart function at such fast HRs. Although the conduction of action potential through the AV node is similar between human and mice, conduction through the atria and ventricles is different between these two species. As such, we need to be conservative when extrapolating our results to humans and other large mammals.

Furthermore, in the present study, we used ISO (a non‐selective β‐adrenergic agonist activating all three β‐ARs) to mimic the effect of sympathetic stimulation of the sinoatrial node and AVN. Previous studies have shown that sympathetic stimulation and ISO (or other exogenous β‐AR agonists) stimulation often do not produce the same effect on HR and conduction rate acceleration (Du et al. 1996; Mantravadi et al. 2007). Sympathetic nerves release norepinephrine that is different from ISO and the distribution of nerve ends and post‐synaptic adrenergic receptors, as well as ion channels, affects the effect of sympathetic stimulation in specific ways. Accordingly, further studies confirming that the Cav3.1 T‐type Ca2+ channel plays an important role in the sympathetic regulation of HR and conduction need to be performed by direct stimulation of the sympathetic nerves.

Conclusions

Our data collectively suggest that Cav3.1 activity enhancement by β‐adrenergic stimulation plays an important role in HR regulation by the SAS in mice. Abnormal Cav3.1 regulation by the SAS system may contribute to abnormal cardiac automaticity. The TTCC can be a target for potential HR slowing treatments.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

YXL, XXZ, CZ, XYZ, YL and ZQ performed the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. CS and MXT handled the animals. YZP, JDM and SRH criticized and revised the manuscript. MXX and XWC organized the study, analysed some of the data, drafted and revised the manuscript. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01‐HL088243 to XWC), American Heart Association (SDG Grant 0730347N to XWC, SDG 15SDG25710230 to XYZ, Predoctoral Fellowship 09PRE2260943 to YXL) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81471678, 81271582, 81071280 to MXX).

Biographies

Yingxin Li received his Ph.D. degree from Temple University, where he focused on ion channel electrophysiology. He found that upregulating T‐type calcium channel activity contributes to the regulation of heart rates. This led him to studying the electrophysiology of cardiomyocytes derived from patient‐specific human induced pluripotent stem cells, which can serve as a platform for precision medicine and drug toxicity evaluations. His career goal is to accelerate drug discovery and development and to implement precision medicine.

Xiaoxiao Zhang graduated from the Fourth Military Medical University with an MD degree in 2010 then joined the department of Ultrasonography of Union Hospital affiliated with Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST). From 2013 to 2016, she was trained as a postdoctoral fellow in Temple University, and then obtained her PhD degree in 2017 from HUST. During her work and study, she developed strong interest in cardiac research.

Linked articles This article is highlighted by a Perspective by Ng. To read this Perspective, visit https://doi.org/10.1113/JP275711.

Edited by: Harold Schultz & Jeffrey Ardell

This is an Editor's Choice article from the 1 April 2018 issue.

Contributor Information

Mingxing Xie, Email: xiemx64@126.com.

Xiongwen Chen, Email: xchen001@temple.edu.

References

- Alig J, Marger L, Mesirca P, Ehmke H, Mangoni ME & Isbrandt D (2009). Control of heart rate by cAMP sensitivity of HCN channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 12189–12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbuti A & DiFrancesco D (2008). Control of cardiac rate by ‘funny’ channels in health and disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 1123, 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borer JS, Deedwania PC, Kim JB & Bohm M (2016). Benefits of heart rate slowing with ivabradine in patients with systolic heart failure and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 118, 1948–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler NJ, Greener ID, Tellez JO, Inada S, Musa H, Molenaar P, Difrancesco D, Baruscotti M, Longhi R, Anderson RH, Billeter R, Sharma V, Sigg DC, Boyett MR & Dobrzynski H (2009). Molecular architecture of the human sinus node: insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation 119, 1562–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Lamping KG, Nuno DW, Barresi R, Prouty SJ, Lavoie JL, Cribbs LL, England SK, Sigmund CD, Weiss RM, Williamson RA, Hill JA & Campbell KP (2003). Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in alpha1H T‐type Ca2+ channels. Science 302, 1416–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs L (2010). T‐type calcium channel expression and function in the diseased heart. Channels 4, 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XJ, Vincan E, Woodcock DM, Milano CA, Dart AM & Woodcock EA (1996). Response to cardiac sympathetic activation in transgenic mice overexpressing beta 2‐adrenergic receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271, H630–H636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov IR, Nikolski VP, Rothenberg F, Greener ID, Li J, Dobrzynski H & Boyett M (2004). Structure‐function relationship in the AV junction. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 280, 952–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Singh MV, Hall DD, Koval OM, Luczak ED, Joiner ML, Chen B, Wu Y, Chaudhary AK, Martins JB, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ, Song LS & Anderson ME (2011). Catecholamine‐independent heart rate increases require Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 4, 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D (2015). Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology. J Physiol 593, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Irisawa H & Kameyama M (1988). Contribution of two types of calcium currents to the pacemaker potentials of rabbit sino‐atrial node cells. J Physiol 395, 233–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huc S, Monteil A, Bidaud I, Barbara G, Chemin J & Lory P (2009). Regulation of T‐type calcium channels: signalling pathways and functional implications. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793, 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser J, Blatter LA & Lipsius SL (2000). Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to automaticity in cat atrial pacemaker cells. J Physiol 524, 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irisawa H & Hagiwara N (1988). Pacemaker mechanism of mammalian sinoatrial node cells. Prog Clin Biol Res 275, 33–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel N, Nakayama H, Chen X, Kubo H, MacDonnell S, Zhang H, Berretta R, Robbins J, Cribbs L, Molkentin JD & Houser SR (2008). Ca2+ influx through T‐ and L‐type Ca2+ channels have different effects on myocyte contractility and induce unique cardiac phenotypes. Circ Res 103, 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaese S & Verheule S (2012). Cardiac electrophysiology in mice: a matter of size. Front Physiol 3, 345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar SP & Pelzer DJ (1995). Modulation by stimulation rate of basal and cAMP‐elevated Ca2+ channel current in guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Gen Physiol 106, 175–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Shinohara T, Joung B, Maruyama M, Choi EK, On YK, Han S, Fishbein MC, Lin SF & Chen PS (2010). Calcium dynamics and the mechanisms of atrioventricular junctional rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol 56, 805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratyev AA, Ponard JG, Munteanu A, Rohr S & Kucera JP (2007). Dynamic changes of cardiac conduction during rapid pacing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292, H1796–H1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA & Vinogradova TM (2010). A coupled SYSTEM of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res 106, 659–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau DH, Roberts‐Thomson KC & Sanders P (2011). Sinus node revisited. Curr Opin Cardiol 26, 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang F, Zhang X, Qi Z, Tang M, Szeto C, Li Y, Zhang H & Chen X (2012). beta‐Adrenergic stimulation increases Cav3.1 activity in cardiac myocytes through protein kinase A. PLoS ONE 7, e39965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang S, Zhang X, Li J, Ai X, Zhang L, Yu D, Ge S, Peng Y & Chen X (2014). Blunted cardiac beta‐adrenergic response as an early indication of cardiac dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cardiovasc Res 103, 60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonnell SM, Garcia‐Rivas G, Scherman JA, Kubo H, Chen X, Valdivia H & Houser SR (2008). Adrenergic regulation of cardiac contractility does not involve phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor at serine 2808. Circ Res 102, e65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ME & Nargeot J (2001). Properties of the hyperpolarization‐activated current (I(f)) in isolated mouse sino‐atrial cells. Cardiovasc Res 52, 51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ME, Traboulsie A, Leoni AL, Couette B, Marger L, Le Quang K, Kupfer E , Cohen‐Solal A, Vilar J, Shin HS, Escande D, Charpentier F, Nargeot J & Lory P (2006). Bradycardia and slowing of the atrioventricular conduction in mice lacking CaV3.1/alpha1G T‐type calcium channels. Circ Res 98, 1422–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantravadi R, Gabris B, Liu T, Choi BR, de Groat WC, Ng GA & Salama G (2007). Autonomic nerve stimulation reverses ventricular repolarization sequence in rabbit hearts. Circ Res 100, e72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesirca P, Torrente AG & Mangoni ME (2015). Functional role of voltage gated Ca(2+) channels in heart automaticity. Front Physiol 6, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteil A, Chemin J, Leuranguer V, Altier C, Mennessier G, Bourinet E, Lory P & Nargeot J (2000). Specific properties of T‐type calcium channels generated by the human alpha 1I subunit. J Biol Chem 275, 16530–16535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H, Bodi I, Correll RN, Chen X, Lorenz J, Houser SR, Robbins J, Schwartz A & Molkentin JD (2009). alpha1G‐dependent T‐type Ca2+ current antagonizes cardiac hypertrophy through a NOS3‐dependent mechanism in mice. J Clin Invest 119, 3787–3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargeot J & Mangoni ME (2006). Ionic channels underlying cardiac automaticity: new insights from genetically‐modified mouse strains. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 99, 856–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Talavera K & Verkhratsky A (2006). T‐type calcium channels: the never ending story. Cell Calcium 40, 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi K, Yoshikawa Y & Takenaka F (1976). Contribution of an electrogenic sodium pump to the response of sinoatrial node cells to acetylcholine. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab 11, 63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K & Iijima T (2010). Cardiac T‐type Ca(2+) channels in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48, 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Reyes E (2003). Molecular physiology of low‐voltage‐activated t‐type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83, 117–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer DK, Chruscinski A, Schauble EH, Bernstein D & Kobilka BK (1999). Cardiovascular and metabolic alterations in mice lacking both beta1‐ and beta2‐adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem 274, 16701–16708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanbe A, Gulick J, Hanks MC, Liang Q, Osinska H & Robbins J (2003). Reengineering inducible cardiac‐specific transgenesis with an attenuated myosin heavy chain promoter. Circ Res 92, 609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara T, Joung B, Kim D, Maruyama M, Luk HN, Chen PS & Lin SF (2010). Induction of atrial ectopic beats with calcium release inhibition: local hierarchy of automaticity in the right atrium. Heart Rhythm 7, 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Zhang X, Li Y, Guan Y, Ai X, Szeto C, Nakayama H, Zhang H, Ge S, Molkentin JD, Houser SR & Chen X (2010). Enhanced basal contractility but reduced excitation‐contraction coupling efficiency and beta‐adrenergic reserve of hearts with increased Cav1.2 activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299, H519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova TM & Lakatta EG (2009). Regulation of basal and reserve cardiac pacemaker function by interactions of cAMP‐mediated PKA‐dependent Ca2+ cycling with surface membrane channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol 47, 456–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Chen YJ, Ge FG & Wang DB (2003). [Comparison of the electrophysiological features between the rhythmic cells of the aortic vestibule and the sinoatrial node in the rabbit]. Sheng Li Xue Bao 55, 405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]