Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study is to determine lymph node features on axillary ultrasound (US) images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy that are associated with residual nodal disease in patients with initial biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

All patients had axillary US performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Axillary US images were centrally reviewed for lymph node size, cortical thickness, and cortical morphologic findings (type I indicated no visible cortex; type II, a hypoechoic cortex ≤ 3 mm; type III, a hypoechoic cortex > 3 mm; type IV, a generalized lobulated hypoechoic cortex; type V, focal hypoechoic cortical lobulation; and type VI, a totally hypoechoic node with no hilum). Lymph node characteristics were compared with final surgical pathologic findings.

RESULTS

Axillary US images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical pathologic findings were available for 611 patients. Residual nodal disease was present in 373 patients (61.0%), and 238 (39.0%) had a complete nodal pathologic response. Increased cortical thickness (mean, 3.5 mm for node-positive disease vs 2.5 mm for node-negative disease) was associated with residual nodal disease. Lymph node short-axis and long-axis diameters were significantly associated with pathologic findings. Patients with nodal morphologic type I or II had the lowest rate of residual nodal disease (51 of 91 patients [56.0%] and 138 of 246 patients (56.1%), respectively), whereas those with nodal morphologic type VI had the highest rate (44 of 55 patients [80.0%]) (p = 0.004). The presence of fatty hilum was significantly associated with node-negative disease (p = 0.0013).

CONCLUSION

Axillary US performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is useful for nodal response assessment, with longer short-axis diameter, longer long-axis diameter, increased cortical thickness, and absence of fatty hilum significantly associated with residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Keywords: lymph node, multicenter trial, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, sentinel lymph node dissection, ultrasound

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is commonly administered to patients with breast cancer who present with node-positive disease. This approach can result in downsizing the index tumor and an increased likelihood of breast-conserving surgery [1–3]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can also result in down-staging axillary nodal disease and allows assessment of the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in both the primary tumor and the lymph nodes. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1071 trial (National Clinical Trials identifier 00881361; ClinicalTrials.gov) was a multiinstitutional trial evaluating the role of sentinel lymph node (SLN) surgery for women presenting with node-positive disease who were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The false-negative rate of SLN surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the Z1071 trial was 12.6% [4]. Patients in the Z1071 trial also underwent axillary US evaluation, and we found that with the addition of axillary US after neoadjuvant chemotherapy to select patients for SLN surgery, the rate of false-negative findings from SLN surgery may potentially decrease to 9.8% [5].

Axillary US has the potential to evaluate the presence of residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and risk-stratify patients to the most appropriate nodal surgery. Although axillary US may help identify patients at higher risk of having residual nodal disease after chemotherapy, the specific imaging features associated with residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy have not been defined. Therefore, if axillary US is to be incorporated into the preoperative imaging protocol for nodal restaging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, then identification of predictive US features is required to minimize the false-negative rate of axillary US and improve the sensitivity and specificity of this modality. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines are commonly used to assess tumor response and include the assessment of abnormal lymph nodes. However, RECIST evaluates only the short axis of the nodes and does not evaluate morphologic features [6].

Most of the published data on the US features of regional nodes are from patient cohorts that did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The goal of the present study was to determine lymph node features on axillary US images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy that were associated with residual nodal disease in patients with initial biopsyproven node-positive breast cancer (clinical T0–T4, N1–N2, M0 disease).

Subjects and Methods

The institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved this HIPAA-compliant prospective multicenter trial. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before study entry.

The Z1071 trial was a prospective multiinstitutional trial that enrolled women with biopsyproven node-positive breast cancer, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and who subsequently underwent SLN surgery and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Women 18 years or older with biopsy-proven invasive breast cancer of clinical T0–T4, N1–N2, M0 completed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and had pretreatment axillary nodal disease documented by fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy were eligible for inclusion in the trial.

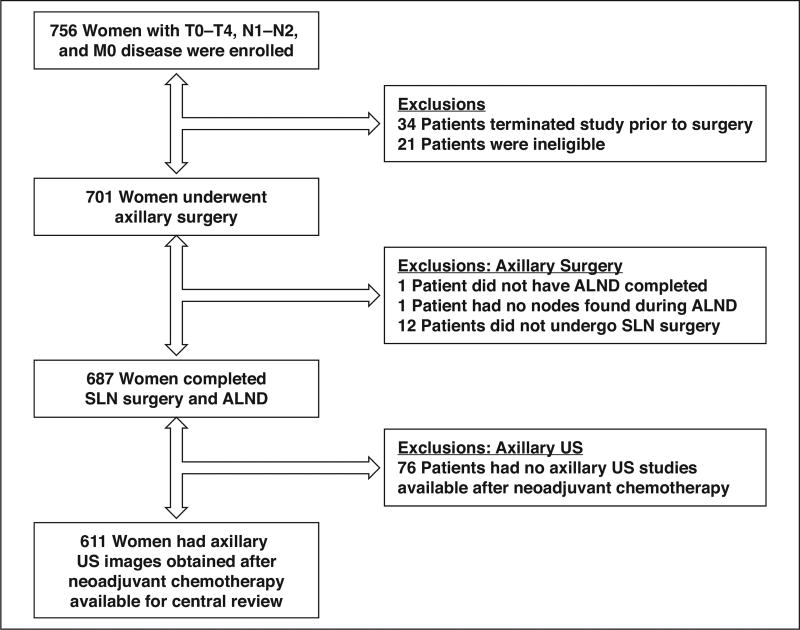

The full description of the study population and trial design has been previously published elsewhere [4, 5]. From July 2009 through June 2011, a total of 756 patients with T0–T4, N1–N2, M0 breast cancer at 136 different academic and private practice institutions were enrolled in the Z1071 trial. Patients who completed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent postchemotherapy and preoperative axillary US within 4 weeks of SLN surgery and ALND are included in this study. Of the 756 patients enrolled, there were 701 eligible patients, 687 of whom completed planned axillary surgery. Axillary US images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were available for central review of 611 of the 687 patients. The reasons for exclusion from the study are provided in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart showing reasons for patient exclusion from study.

ALND = axillary lymph node dissection, SLN = sentinel lymph node, US = ultrasound.

Axillary Ultrasound

Axillary US was performed at the local sites with a recommendation to use commercially available equipment that met the following minimal requirements: a broad-bandwidth linear array transducer with a minimum frequency of at least 10–17 MHz and high-resolution imaging capability at depths of 2–45 mm. The radiologist at each local site performed and interpreted the examinations. A central radiologist provided quality-control checks and supplemental materials for training purposes.

Imaging Review

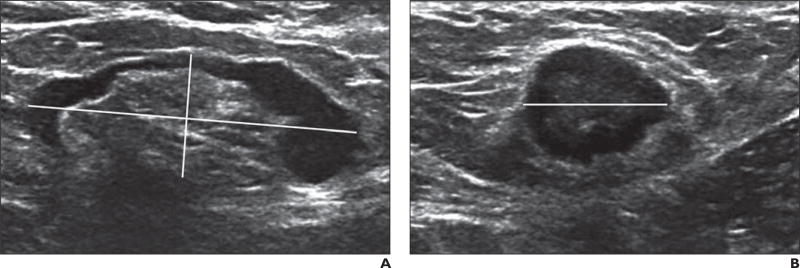

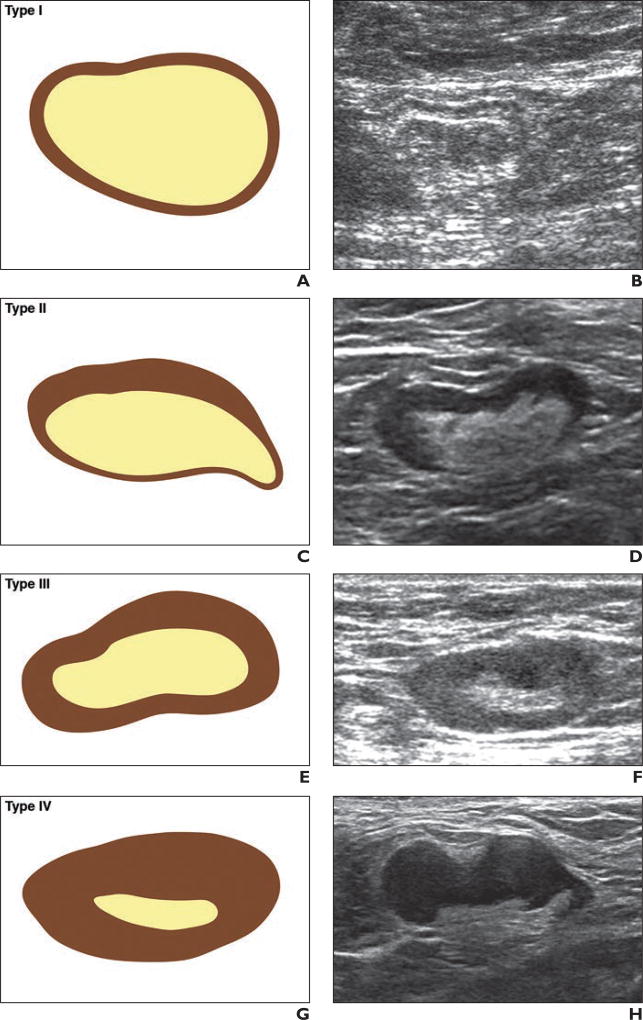

Hard copies or digital images of the axillary US images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were requested for submission by site radiologists to the Quality Assurance Review Center for central review. Remote central review of archived images was conducted by the study radiologist, who had 15 years of experience and was blinded to the imaging, pathologic, and surgical reports. The software and operating database at the review center enabled the central reviewer to measure the lymph nodes, provide feedback to the sites, and archive comments on each study. Sites were requested to submit the size of the biopsyproven lymph node or the largest node, with measurements (expressed in millimeters) obtained in three planes (i.e., the long axis of the node, the short axis of the node, and a third plane orthogonal or perpendicular to two prior measurements) and image plane location and orientation labeling (Fig. 2). The largest diameter of each node was defined as the long-axis diameter, and the diameter perpendicular to the long-axis diameter was defined as the short-axis diameter. The ratio of the long axis to the short axis (the ratio of the long-axis diameter to the short-axis diameter) of the enlarged or index lymph node was calculated [7]. The axillary lymph nodes were classified at the local sites and at central review as either normal or abnormal (suspicious in appearance), or it was noted that no lymph nodes were visualized. When possible, on the basis of morphologic findings, the nodes were classified into one of the following types on the basis of the appearance of the nodal cortex and hilum: type I, which denoted a hyperechoic cortex that was not visible; type II, a thin (≤ 3 mm) hypoechoic cortex; type III, a hypoechoic cortex thicker than 3 mm; type IV, a generalized lobulated hypoechoic cortex; type V, focal hypoechoic cortical lobulation; and type VI, a totally hypoechoic node with no hilum [8–10] (Fig. 3). Other lymph node features that were recorded included cortical thickness and the presence or absence of an echogenic nodal hilum of the most abnormal or suspicious-appearing lymph node.

Fig. 2. Lymph node measurement technique in 58-year-old woman with biopsy-proven nodal metastases from ductal carcinoma in situ.

A and B, Axillary ultrasound images show how lymph node measurements are obtained in three planes: longitudinal (horizontally slanted line) and short-axis (vertically slanted line) diameters (A) and transverse diameter (B, horizontal line).

Fig. 3. Drawings and corresponding axillary ultrasound (US) images of six types of nodal morphologic classification. (Drawings by Kage KM; c2017 The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center).

A and B, Drawing (A) and axillary US image (B) representing type I morphologic classification of normal node. Hyperechoic hilum is visible, and there is almost no visible cortex.

C and D, Drawing (C) and axillary US image (D) representing type II morphologic classification of normal node. Hyperechoic hilum is visible, and there is thin (≤ 3 mm) hypoechoic cortex.

E and F, Drawing (E) and axillary US image (F) representing type III morphologic classification of abnormal node. Hyperechoic hilum is visible, and hypoechoic cortex is thicker than 3 mm.

G and H, Drawing (G) and axillary US image (H) representing type IV morphologic classification of abnormal node. Hyperechoic hilum is visible but is effaced, and there is generalized lobulated hypoechoic cortex.

I and J, Drawing (I) and axillary US image (J) representing type V morphologic classification of abnormal node. Hyperechoic hilum is visible, and there is focal hypoechoic cortical lobulation.

K and L, Drawing (K) and axillary US image (L) representing type VI morphologic classification of abnormal node. No hilum is visible, and the node is totally hypoechoic.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were made using a two-sample t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test (whichever was more appropriate for the distribution). Comparisons of categoric variables between groups were done using a chi-square test or Fisher exact test if expected cell sizes were too small for the chi-square test. Multivariable logistic models were used to determine whether axillary US variables remained significantly associated with residual nodal disease on pathologic analysis in the presence of the other variables. If variables were highly correlated, only one of the correlated variables was selected to be in the model. Clinical, tumor, and treatment variables included in the model were tumor clinical T category, tumor subtype, surgery type, and adjuvant radiation. Results of the logistic models were summarized as odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% CIs. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered to denote statistical significance. Analyses were performed using statistical software (SAS, version 9.3, SAS Institute).

Results

Of 611 patients, 373 (61.0%) had lymph nodes with positive pathologic findings, and 238 (39.0%) had lymph nodes with negative pathologic findings. No clinically significant differences were noted between the group of 611 patients who were included in this study and the group of patients who were not included, with the exception of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status: the percentage of patients with a performance status of 0 was 82.0% for the included patients versus 69.7% for the patients who were not included [4, 11]. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Enrolled in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1071 Trial Who Had Postneoadjuvant Chemotherapy Axillary Ultrasound Images Available (n = 611)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (y) | |

| Mean ± SD | 50.2 ± 11.0 |

| Median (minimum value, maximum value) | 50 (23, 93) |

| Clinical T category at diagnosis | |

| T0 or Tis | 7 (1.1) |

| T1 | 83 (13.6) |

| T2 | 334 (54.7) |

| T3 | 159 (26.0) |

| T4 | 28 (4.6) |

| Clinical nodal category at presentation | |

| N1 | 579 (94.8) |

| N2 | 32 (5.2) |

| Subtype | |

| ErbB-2a positive | 179 (29.3) |

| Hormone positive and ErbB-2 negative | 276 (45.2) |

| Triple-receptor negative | 156 (25.5) |

| Tumor histologic finding | |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 540 (88.4) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 34 (5.6) |

| Mixed | 10 (1.6) |

| Other | 27 (4.4) |

| Clinical assessment of the axilla after chemotherapy | |

| No palpable adenopathy | 512 (83.8) |

| Palpable lymph nodes | 74 (12.1) |

| Fixed or matted lymph nodes | 4 (0.7) |

| Not reported | 21 (3.4) |

Note—Except where otherwise indicated, data are number (%) of patients. Tis = cancers cells are growing in the most superficial layer of tissue but are not growing into deeper tissues.

ErbB-2 is also known as HER2/neu.

Lymph Node Size on Axillary Ultrasound

A total of 501 patients were included in the analysis of lymph node size; of these, 195 (39.1%) had node-negative status, 304 (60.6%) had node-positive status, and two patients had unknown lymph node status. One hundred ten patients were excluded either because the submitted axillary US images did not show any residual lymph nodes or because the axillary US images were not in DICOM format to allow central review measurement. Measurements of both the short-axis diameter and long-axis diameter of the index biopsy-proven metastatic node were statistically different between patients with residual nodal disease at surgery and those with complete nodal pathologic response (Table 2). The median short-axis diameter of the index lymph node was 6.0 mm (range, 0.0–24.0 mm) in patients with residual disease and 6.0 mm (range, 0.0–14.0 mm) in patients with no residual nodal disease (p < 0.0001). The median long-axis diameter was 12.0 mm (range, 0.0–46.0 mm) in patients with residual disease and 13.0 mm (range, 0.0–37.0 mm) in patients with no residual nodal disease (p = 0.016). The ratios of long-axis diameters to short-axis diameters also showed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.045) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Lymph Node Size and Morphologic and Pathologic Findings

| Ultrasound Feature | Finding on Final Pathologic Analysis | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Node-Negative Disease |

Node-Positive Disease |

|||

|

| ||||

| Short-axis diameter of lymph node (mm) (n = 501) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Median (range) | 6.0 (0–14.0) | 6.0 (0–24.0) | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.4) | 7.0 (3.1) | ||

| Long-axis diameter of lymph node (mm) (n = 501) | 0.016 | |||

| Median (range) | 12.0 (0–37.0) | 13.0 (0–46.0) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.7 (5.7) | 14.2(6.4) | ||

| Ratio of long-axis diameter to short-axis diameter (mm) (n = 501) | 0.045 | |||

| Median (range) | 2.25 (1.0–6.0) | 2.0 (1.0–16.0) | 1.22 (1.00–1.50) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.38 (0.92) | 2.18 (1.09) | ||

| Node morphologic finding (n = 611)b | 0.004 | |||

| Node not seen | 39 (42.4) | 53 (57.6) | Reference | |

| Type I | 40 (44.0) | 51 (56.0) | 1.07 (0.59–1.91) | |

| Type II | 108 (43.9) | 138 (56.1) | 1.06 (0.66–1.73) | |

| Type III | 20 (40.8) | 29 (59.2) | 0.94 (0.46–1.90) | |

| Type IV | 9 (20.5) | 35 (79.5) | 0.35 (0.15–0.81) | |

| Type V | 11 (32.4) | 23 (67.6) | 0.65 (0.28–1.49) | |

| Type VI | 11 (20.0) | 44 (80.0) | 0.34 (0.16–0.74) | |

| Fatty hilum (n = 519)c | 0.0013d | |||

| Not visible | 11(19.0) | 47(81.0) | Reference | |

| Visible | 188 (40.8) | 273 (59.2) | 2.94 (1.49–5.82) | |

| Cortical thickness (n = 493)e | < 0.0001d | |||

| ≤ 3 mm | 152 (44.2) | 192 (55.8) | Reference | |

| > 3 mm | 38 (25.5) | 111 (74.5) | 0.43 (0.28–0.66) | |

For nodes with clinical nodal category N0.

Type I lymph nodes were hyperechoic with no visible cortex, type II nodes were thin (< 3 mm) with a hypoechoic cortex; type III nodes were hypoechoic with a cortex thicker than 3 mm, type IV nodes had a generalized lobulated hypoechoic cortex, type V nodes had focal hypoechoic cortical lobulation, and type VI nodes were totally hypoechoic with no hilum.

Limited to cases with lymph nodes visualized on axillary ultrasound.

Statistically significant.

Limited to cases with DICOM images and visible residual nodes for central review measurement.

Lymph Node Morphologic Findings on Axillary Ultrasound

Of 611 patients, 337 (55.2%) had normal nodal morphologic classifications (type I and II), and 92 (15.1%) had no visible axillary node seen on the ultrasound images submitted (Table 2). The morphologic type noted on axillary US correlated with pathologic findings. Patients with nodes with type I morphologic classification had the highest likelihood of having no residual nodal disease at surgery, although there was not a significant difference in the proportions of patients with no residual nodal disease among the type I group, the type II group, and the group for whom no lymph nodes were seen. Among the patients with nodes of morphologic types III–VI, a correlation was noted between residual nodal disease and morphologic findings on axillary US, with residual nodal disease found in 59.2% of patients with type III nodes, 79.6% of those with type IV, 67.6% of patients with type V, and 80.0% of those with type VI (Table 2).

Axillary US findings were also associated with the size of the metastases within the lymph node. The median size of the largest focus of residual disease in the lymph node was significantly smaller for patients with radiographically normal nodal assessment (i.e., the type I group, the type II group, and the group for whom lymph nodes were not seen) at 6.5 mm compared with 11 mm in patients with type III–VI nodes (p < 0.0001).

Lymph Node Fatty Hilum Assessment

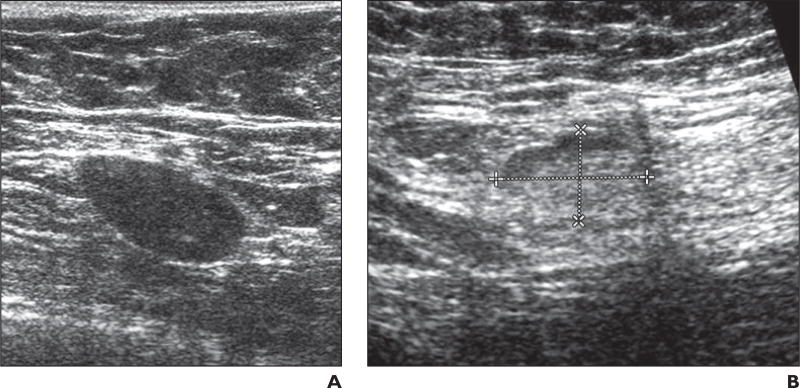

A total of 519 patients were evaluable for fatty hilum. The presence or absence of a visible fatty hilum within the lymph node was associated with residual nodal disease status on final pathologic analysis. When axillary US showed persistent loss of the fatty hilum in the node, final pathologic analysis indicated residual tumor within the node in 47 of 58 patients (81.0%) (Fig. 4A). Of the 461 cases with a visible fatty hilum on axillary US, 273 (59.2%) had residual nodal disease on final pathologic analysis (p = 0.0013) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Two patients with fatty hilum within lymph node.

A, 50-year-old woman with biopsy-proven nodal metastases from invasive breast cancer. Ultrasound examination performed after patient received chemotherapy revealed lymph node that remained abnormal with persistent loss of fatty hilum in node (type VI). Final pathologic analysis confirmed 0.7-cm metastasis in this 2.4-cm lymph node.

B, 57-year-old woman with biopsyproven metastatic node from invasive breast cancer. Ultrasound examination performed after patient received chemotherapy revealed normal-appearing lymph node with visible fatty hilum suggesting no residual disease. Dashed lines show long and short axis of node. Final pathologic analysis revealed 0.3-cm metastasis in this 1.8-cm lymph node.

Lymph Node Cortical Thickness

For 493 cases, cortical thickness could be measured on central review of the images. The mean (± SD) cortical thickness was significantly larger in cases with residual nodal disease on pathologic analysis (3.5 ± 3.24 mm) compared with those with complete nodal response (2.5 mm ± 1.66) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). Of the 344 cases with cortical thickening of 3 mm or less, 192 (55.8%) had residual nodal disease on final pathologic analysis, whereas of the 149 cases with cortical thickness greater than 3 mm, 111 (74.5%) had residual disease on final pathologic analysis (p < 0.0001). In this subset of 149 cases with a cortical thickness greater than 3 mm, 135 cases had cortical thickness greater than 3 mm but less than 10 mm. Ninety-six of these 135 cases (71.1%) had residual nodal disease on final pathologic analysis. Of the remaining 14 of 149 cases, the cortical thickness was greater than 10 mm, and all of these patients had residual nodal disease on final pathologic analysis.

Fig. 5. Cortical thickness of lymph node in two patients.

A, 33-year-old woman with response to chemotherapy. Axillary ultrasound image showed benign-appearing lymph node (asterisk) with cortical thickness of 1.4 mm (dashed line). Final pathologic analysis revealed no residual tumor.

B, 53-year-old woman with residual nodal disease. Axillary ultrasound showed hypoechoic lymph node (asterisk) with persistent cortical thickness of 4.6 mm (dashed line). Final pathologic analysis confirmed residual disease in lymph node.

All four lymph node features on axillary US (short-axis diameter, long-axis diameter, presence or absence of a fatty hilum, and cortical thickness) are significantly associated with lymph node residual disease status in this cohort. It was not possible to perform a multivariable analysis with all four variables in the model because of the high level of correlation among the variables. However, each variable was significantly associated with lymph node residual disease status in the multivariable model that included the variable and adjusted for tumor clinical T category, tumor subtype, surgery type, and adjuvant radiation.

Discussion

Axillary US is often performed preoperatively to recategorize regional nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinical practice; however, there are limited data from clinical trials looking specifically at the ultrasound features that identify nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. As a result, there are no well-established or standardized criteria for categorizing suspicious nodes from nonsuspicious nodes in the preoperative postneoadjuvant therapy setting. In this study, we reviewed specific imaging features, including lymph node size, cortical thickness, and presence of fatty hilum, to determine which ultrasound features best predict residual disease and are the most relevant features to be evaluated and reported when performing preoperative nodal ultrasound after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Our data show that lymph node size, the cortical thickness of the most abnormal lymph node, and the presence or loss of the fatty hilum are the most important criteria to assess when axillary US is performed to evaluate residual nodal disease status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Our data support the current practice of reporting lymph node size, specifically the short-axis diameter, because this is associated with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This is also the case for patients who are not treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. However, additional morphologic features, such as cortical thickness and presence of fatty hilum, should also be assessed in the post– neoadjuvant chemotherapy setting.

Change in lymph node size traditionally has been widely used to assess response to therapy and is included in the RECIST 1.1 guidelines that require assessment of the short-axis diameter of lymph nodes as one of the predictors of the presence or absence of metastatic disease [12, 13]. Our data validate this practice. The present study shows that short-axis diameter, long-axis diameter, and the ratio of the long-axis diameter to the short-axis diameter after neoadjuvant chemotherapy are all associated with residual nodal disease. The strength of the association of the latter two measurements is weaker (as measured by the ORs) than that of the short-axis diameter. The median short-axis diameter values are the same (6 mm) for both the group with residual disease and the group with complete response; however, for this comparison, the significant p value represents a difference in the distributions of short-axis diameter between the two groups. The mean value is 5.6 mm for the group with no residual disease and 7 mm for the group with residual disease. The mean difference in the long-axis measurement between those with residual disease and those with complete nodal response was 1 mm, which was statistically significant. In practice, a 1-mm difference likely is not clinically important and can occur with interobserver variability. On the basis of our observations, the utilization of lymph node size on ultrasound, as described in the RECIST 1.1 guidelines for lymph node assessment, may be sufficient. However, qualitative morphologic assessment of the presence of fatty hilum may be easier and quicker to perform as an indicator of residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The ability to visualize the fatty hilum of a lymph node is related to how thick or deformed the nodal cortex is. The thicker the cortex, the more likely the cortex would efface the fatty hilum and obscure the ability to visualize the hilum. Because a range of possible imaging findings exists, the category types used in the Z1071 trial encompassed this spectrum of morphologic findings, which appears to best reflect residual disease. When the fatty hilum was not visible on ultrasound, most patients (81.4%) had residual tumor on final pathologic analysis (p = 0.0013). This observation is also supported by other publications about axillary US examination of patients who were not treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [14–16]. The positive predictive value for nodal metastases was reported as 93.1% for nodal ultrasound with core biopsy in a retrospective study of 662 patients with newly suspected breast cancer [14]. It has been suggested that the absence of a fatty hilum on imaging be an indicator for performing biopsy [17, 18].

Increased cortical thickness is associated with residual nodal disease in this study, with a lower likelihood of residual disease in nodes with type I or II morphologic findings or in cases with no visible residual lymph nodes, compared with nodes with type III–VI morphologic findings. In addition, the higher the morphologic type number, the larger the residual metastatic focus in the lymph nodes. In the type I group, the type II group, and the group with no visible lymph node, residual nodal disease, when present, was smaller. This makes sense because small foci of residual disease do not have echogenicity different from that of the cortex, making detection with imaging difficult if the residual disease does not deform the cortex or cause cortical thickening. When the residual nodal disease causes deformity of the cortex, effacement of the fatty hilum (types IV–VI), or both, axillary US performed better and was able to detect 73% of lymph nodes with positive pathologic findings. The positive predictive value of cortical thickness in our study (71.8%) is consistent with published data [8] from a patient population that did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

A meta-analysis of 31 studies that included 8232 cases of preoperative axillary staging procedures noted that approximately 50% of women with axillary nodal involvement could be identified preoperatively with axillary US combined with ultrasound-guided biopsy [7]. From this, the investigators concluded that axillary US is useful in staging the axilla of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Positive nodal disease on imaging was also associated with an increased nodal tumor burden [19]. As an example, one abnormal lymph node detected on ultrasound may correspond to multiple (three to five or more) metastatic nodes found on final pathologic analysis [20, 21]. This indicates that ultrasound potentially identifies patients with a higher burden of disease in the nodes. Other trials, such as the SENTINA study (which evaluated sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy) [6], incorporated preoperative axillary US in the evaluation of residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy but enrolled only patients with normal axillary US findings after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

This trial had several limitations despite its prospective nature. Preoperative axillary US was not mandatory during trial development because of a concern about accrual, and imaging was not the primary objective. As a result, ultrasound images obtained before neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not submitted in every case. Comparison of the ultrasound images obtained before and after chemotherapy was not discussed in this article because this study focuses on ultrasound images obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and correlates findings with pathologic results. In cases without a clip placed within the biopsied node, it was not possible to determine which node was biopsied before neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Axillary US is operator dependent, and it was assumed that the single axillary node on the submitted image was the same node that was biopsied. The central review of axillary US images presented other challenges, including the limited quality of images submitted by the sites, non-DICOM images that precluded central review measurement, or absence of images of axillary nodes.

We found that use of measurement of the short-axis diameter, morphologic classification on the basis of cortical thickness measurement, and assessment of the presence or loss of the fatty hilum are the most important parameters in the assessment of nodal status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (awards U10CA180821 and U10CA180882 to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and awards CA076001, U10CA180858, U10CA180844, U10CA180799, and U10CA180790).

Footnotes

Based on a presentation at the Radiological Society of North America 2014 annual meeting, Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Dominici LS, Negron Gonzalez VM, Buzdar AU, et al. Cytologically proven axillary lymph node metastases are eradicated in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy with concurrent trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2884–2889. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Redmond C, Fisher ER, et al. Ten-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing radical mastectomy and total mastectomy with or without radiation. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:674–681. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503143121102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuerer HM, Sahin AA, Hunt KK, et al. Incidence and impact of documented eradication of breast cancer axillary lymph node metastases before surgery in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:72–78. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1455–1461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boughey JC, Ballman KV, Hunt KK, et al. Axillary ultrasound after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and its impact on sentinel lymph node surgery: results from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1071 Trial (Alliance) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3386–3393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diepstraten SC, Sever AR, Buckens CF, et al. Value of preoperative ultrasound-guided axillary lymph node biopsy for preventing complete axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:51–59. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedi DG, Krishnamurthy R, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Cortical morphologic features of axillary lymph nodes as a predictor of metastasis in breast cancer: in vitro sonographic study. AJR. 2008;191:646–652. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnamurthy S, Sneige N, Bedi DG, et al. Role of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of indeterminate and suspicious axillary lymph nodes in the initial staging of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:982–988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koelliker SL, Chung MA, Mainiero MB, Steinhoff MM, Cady B. Axillary lymph nodes: US-guided fine-needle aspiration for initial staging of breast cancer-correlation with primary tumor size. Radiology. 2008;246:81–89. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463061463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oken M, Creech R, Tormey D, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Persijn van Meerten EL, Gelderblom H, Bloem JL. RECIST revised: implications for the radiologist. A review article on the modified RECIST guideline. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1456–1467. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1685-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya Nikhill H, et al. Revised RECIST guideline version 1.1: what oncologists want to know and what radiologists need to know. AJR. 2010;195:281–289. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmore LC, Appleton CM, Zhou G, Margenthaler JA. Axillary ultrasound in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: which features are predictive of disease? J Surg Res. 2013;184:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Ortega MJ, Benito MA, Vahamonde EF, et al. Pretreatment axillary ultrasonography and core biopsy in patients with suspected breast cancer: diagnostic accuracy and impact on management. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur N, Sharma P, Garg A, Tandon A. Accuracy of individual descriptors and grading of nodal involvement by AUS in patients of breast cancer. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:930596. doi: 10.1155/2013/930596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ertan K, Linsler C, di Liberto A, Ong MF, Solomayer E, Endrikat J. Axillary ultrasound for breast cancer staging: an attempt to identify clinical/ histopathological factors impacting diagnostic performance. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2013;7:35–40. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hieken TJ, Boughey JC, Jones KN, Shah SS, Glazebrook KN. Imaging response and residual metastatic axillary lymph node disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3199–3204. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boland MR, Prichard RS, Daskalova I, et al. Axillary nodal burden in primary breast cancer patients with positive pre-operative ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology: management in the era of ACOSOG Z011. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrell TP, Adams NC, Stenson M, et al. The Z0011 Trial: is this the end of AUS in the pre-operative assessment of breast cancer patients? Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2682–2687. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hieken TJ, Trull BC, Boughey JC, et al. Preoperative axillary imaging with percutaneous lymph node biopsy is valuable in the contemporary management of patients with breast cancer. Surgery. 2013;154:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]